1911 vs. 1911A1: What’s the Difference?

March 25th, 2024

8 minute read

Editor’s Note: In today’s article, T. Logan Metesh compares the M1911 and M1911A1 pistols to help you understand the difference between the two models. A special thanks to Rock Island Auction Co. for allowing us to use some of the photos in this article.

For the purposes of this article, 1911 and M1911 are used interchangeably. Additionally, the differences discussed are the general feature changes. Many, many variations were created throughout two world wars and the interwar period.

This article is not intended to be a defining treatise on all of the variations; instead it is presented to help a newcomer to the 1911-style pistols understand some of the differences to look for when seeing these guns.

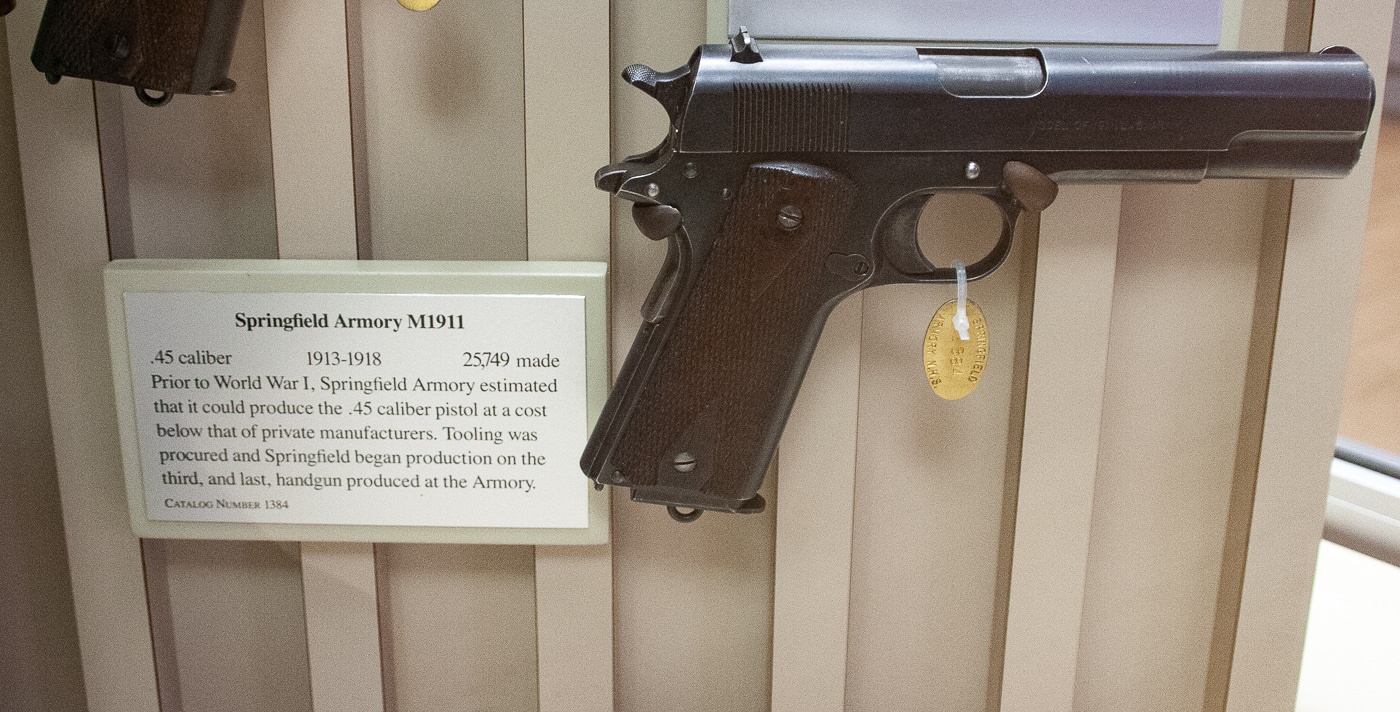

For most people, referring to the .45 ACP semi-automatic pistol designed by John Moses Browning and adopted by the U.S. Military in March 1911 simply as a “1911” will suffice. Avid shooters can, more or less, picture the design in their head and differentiate between it and other handguns.

For most people, however, the difference between nomenclature of “1911” and “1911A1” is of little to no significance. To the untrained eye, the guns still look basically the same.

Make no mistake, though, that there are indeed distinct differences between the the M1911 pistol and its A1 progeny. After all, if there wasn’t, then there would have been no need to alter the nomenclature in the first place.

When Did the M1911A1 Appear?

There is often a misconception that “1911” refers to everything made before World War II and “1911A1” refers to everything made during and after World War II. This is not the case.

Design changes began undergoing testing on November 12, 1920, just two years after World War I ended in 1918. As with most things involving the government, progress was steady, but slow. The pistol design and nomenclature of “1911A1” was officially adopted on May 20, 1926 — some 15 years before the United States got involved in World War II.

What are the differences between the two designs, and why were the changes made?

Grips/Stocks

Whether you call them grips or stocks is up to you, but the difference can be seen immediately between those on a 1911 and a 1911A1. The stocks on a 1911 were made of walnut, checkered, and had diamonds around the screw holes.

In 1924, the diamonds were removed to streamline production and to provide for some more lines of checkering to improve the shooter’s grip. They were, however, still made of walnut.

It wasn’t until 1931 — and five years after the adoption of the 1911A1 — that an alternative to wood was sought for the grip panels. Initially, aluminum and Bakelite were tested, but they didn’t pan out. A reddish-brown plastic material embedded with fibers called Coltrock was used starting in 1940, but it was too brittle to stand up to the rigors of military use.

Designers worked on the material, improved it by reducing the amount of fibers used, and reintroduced it as a drab brown called Coltwood, but it, too, didn’t see much use.

Finally, Coltwood Plastic came along. This eliminated the use of fibers and was implemented in 1941. This material was used by all of the manufacturers contracted to produce the 1911A1.

Trigger

Compared to the 1911A1, the trigger on a 1911 is exponentially longer and the difference is immediately noticed. It protrudes much farther from the frame than the trigger on a 1911A1.

The trigger was shortened to make it easier for shooters of all sizes to have a better reach. During design testing, it was noted that the 1911’s trigger size was “unnecessary” and was complained about by many, including “men with fairly large hands.” This was done in the first half of 1922.

Finally, in the second half of 1922, the face of the trigger was knurled/checkered to provide better purchase with the trigger finger. Eliminating the long trigger resulted in a gun that was easier to shoot for many people.

Frame Contours

In conjunction with the shorter trigger, the frame around the trigger was also modified for better reach and grip. This was done by cutting scalloped contours on each side of the frame at the rear of the trigger guard above the magazine release.

These scallops on the frame allow the shooter better access to the trigger face, increasing his ability to press straight to the rear rather than putting pressure on one side or the other and pulling the shot. For folks with smaller hands, this can be a big benefit.

Sights

A few different changes were made to the 1911’s sights during the inter-war and WWII eras. First was a widening of the front sight to a uniform width instead of tapering up to a thinner shape as was first designed. This was done in 1923. By World War II, the front sight was enlarged again, again to a uniform width overall.

In 1942, the front sight underwent another change; serrations were added on the edge facing the shooter. At the same time, the rear sight changed from a U-notch to a square notch.

As a note, many modern interpretations of the M1911/M1911A1 pistols include better sights than either of the original offerings. For example, the Springfield Armory 1911 Mil-Spec comes with 3-dot sights.

Mainspring Housing

The mainspring housing on a 1911 is flat. It was observed that this led to a tendency of new shooters in WWI to aim low. To correct this, a “hump” was recommended in 1921. Designed by Lt. William Wenstrom, this new mainspring housing would give “a more desirable angle to the rear of the grip” and “force the soldier to take the correct grip with the hand well up on the stock.”

Visually, the arched mainspring housing is one of the quickest ways of determining the difference between the models. If you see a flat mainspring housing, it is likely an original M1911 while the arched version is likely to be an -A1 model.

In 1922, it was recommended that the new humped mainspring housing be knurled for a better grip. This was adopted, but it was changed to serrations during World War II.

Hammer

Pinching of the web of the hand between the thumb and index finger with the 1911 was a big problem for shooters of all sizes. The “pinching” is known as hammer bite.

The stopgap solution was to wear a piece of tape over that spot to protect the skin. Of course, this isn’t feasible in the long term, especially so in battle conditions where sweat, dirt, etc. would lead to the tape falling off.

Initially, the hammer spur was deemed short enough already and making it shorter was “not regarded with much favor.” By 1939, however, the hammer had been shortened to provide for increased performance and shooter comfort. During World War II, it was narrowed a bit as well.

Possibly equally important to the changes to the hammer spur was the addition of a longer grip safety spur…

Grip Safety

When the hammer was deemed short enough in 1920 and the decision to leave it alone was made, the initial remedy was to modify the grip safety.

The comb of the grip safety was extended to protect the hand webbing. The military wanted to project the shoulder of the receiver, too, but that would have required a new design and more tooling (aka money) to do so, so the idea was shelved for the time being.

What We See Today?

While the above changes are the general guidelines used to differentiate between a 1911 and a 1911A1, the truth is that the differences are much more nuanced and far less cut and dry.

This due in part to the fact that the changes were not made all at once. Consequently, you’ll see some guns that exhibit some but not all of the changes. Adding to that, the basic design of the 1911 was in service as the official U.S. sidearm from 1911 until 1984. These guns were worked and reworked repeatedly over their 74-year service life.

Armorers were not concerned if the replacement parts matched the original issue of the gun; they just needed it to work. Most surplus military-issue 1911s and 1911A1s that you come across will exhibit a mix of parts from different eras. As a result, 1911s and 1911A1s that are found in all-original, as-built condition command a premium on the collector market.

At the end of the day, call it a 1911, or call it a 1911A1. For the person who just wants to own an example of the longest-serving sidearm of the U.S. Military, it will make little to no difference. Just know that there are actual differences between the two, and you will undoubtedly run across someone at some point in time who will want to call you out for misusing the terms.

My advice is to acknowledge it, shrug it off, and go put more rounds downrange!

The Modern Mil-Spec

Speaking of classic 1911 pistols, Springfield Armory offers its own take on the proven 1911 pistol. The 1911 Mil-Spec pistol is a newly manufactured .45 ACP that is inspired by the 1911-A1, but has some additional modernized updates.

For example, to ensure maximum reliability, the ejection port has been lowered and flared to ensure consistent ejection of fired brass pulled from the pistol’s stainless steel match-grade barrel (another upgrade).

Another enhancement is a slightly beveled magazine well for easier reloads. Additionally, the Mil-Spec has big, easy-to-see three dot sights. Round that out with checkered wood grips, and you have a brand new pistol that captures the charm of the original military pistol, but with some very nice modern enhancements.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

942

942