A Revolutionary Weapon: The Turning Breech Ferguson Rifle

March 29th, 2022

10 minute read

Editor’s Note: Following is an excerpt from Rifles, Rangers & Revolution by Jeff John. If you would like to pick up a copy for yourself, it is available at Amazon.com. To learn more, visit Jeff-John.com.

British ordnance received an order for 100 very unusual rifles that probably couldn’t have changed the course of the American Revolutionary War, but would have revolutionized small arms in future wars had the innovative tactics and rifles been nurtured.

These were called Pattern 1776 Rifles, normally with the name of the inventor Capt. Patrick Ferguson added. Their fame has driven the preceding P1776 rifle out of the limelight almost entirely. They are held up as ultimate secret weapons or derided as impossibly expensive vanity toys. The truth is stranger.

A Revolutionary vs. the Revolutionaries

Patrick Ferguson is often denigrated today because he didn’t really invent the rifle bearing his name (despite having patents) and its tactical superiority largely unproven. A turning-breech rifle had been available to discriminating sportsman for quite some time already. The Board of Ordnance even toyed with such a design as early 1762 for specialist troops, having gone to the trouble of ordering 25 built. So this wasn’t new, unproven technology, just never perfected. Ferguson’s improvement gave the rifle the ability to better manage the fouling of the powder for sustained, rapid fire, something essential to a military rifle. He is also credited with the tapered chamber centering the ball into the rifling, and added the bayonet other rifles eschewed.

The construction has some unique points. The Ferguson shares a stock design very similar to the P1776 muzzleloader, and the Brown Bess parentage of both becomes patently obvious side-by-side (To learn more about the Brown Bess rifle, click here). The grip rail buttstock is present, there is no patchbox (the Ferguson of all rifles doesn’t really need one), and the forearm has the nifty bulge for the left hand. The barrel is held with three keys or “slides,” and the rammer pipes are very similar to the P1776 muzzleloader (both quite different from the Brown Bess).

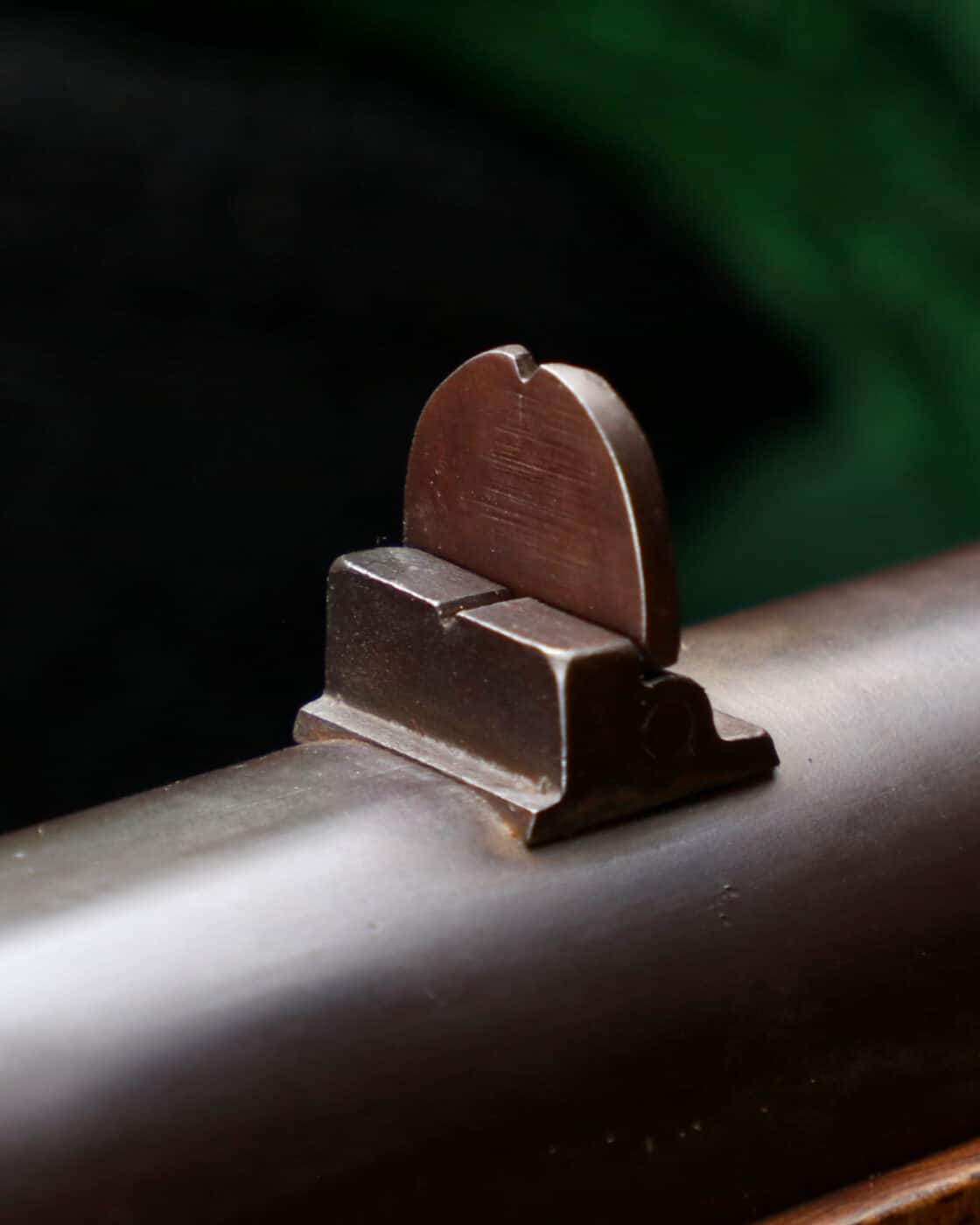

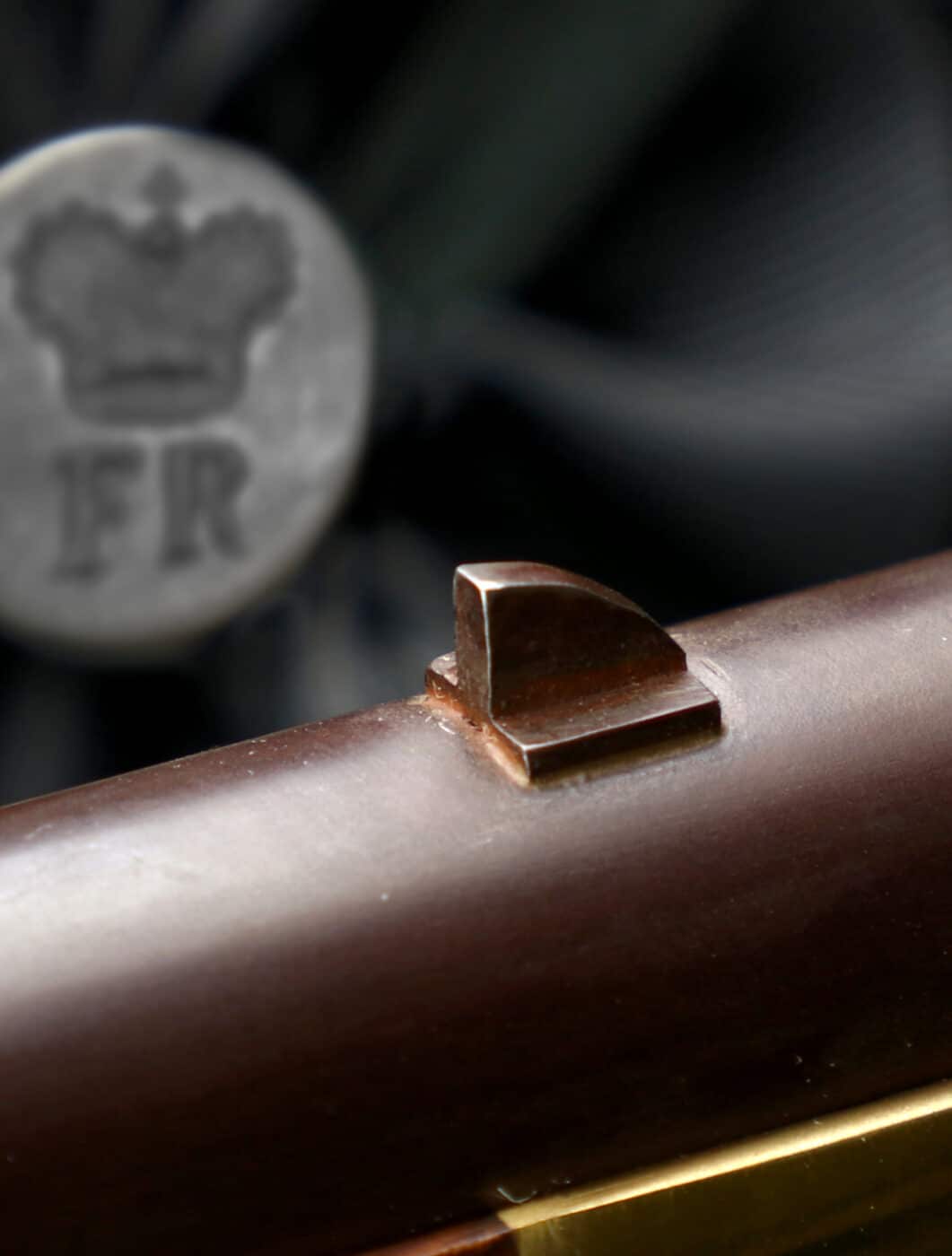

The lock is substantially smaller than the musket lock and similar in size and operation to the P1776 muzzleloader, but they are not interchangeable in size or parts. The trigger is pinned to the wood and the pull crisp but heavy at 7 pounds. The rifle itself weighs 9 pounds, 9 ounces. The balance point is right under the rear sight, and the rifle holds and aims very nicely offhand. The rear sight has one fixed leaf, and one very tall folding leaf. The front sight is sweated onto the barrel far enough back to allow the bayonet to be affixed. The bayonet lug is sweated on underneath the barrel. The round, tapered 33-inch barrel isn’t very thick or heavy and the balance closer to the action due to the heavy screw-breech, but the rifle holds very well for offhand shooting.

The sling swivels are sufficiently odd enough for comment. The rear swivel is affixed to the side of the stock where it is strongest, and keeps the sling out of the way for loading. The swivel is mounted to a square stud set into the wood at a slight downward angle, and a pin driven through it from the top. The swivel itself is free to move on one axis only, and does not rotate.

The front swivel is odd being a simple half-round loop rather than a flat loop that would conform to the shape of the sling as used on the other P1776 and Brown Bess. It is a style of sling swivel mostly found on rifles of Germanic origin. A screw passes through the wood securing it, and the sling may be left in place when dismounting the action from the stock.

Unfulfilled Promise

Patrick Ferguson, his namesake rifle and 100 men were assigned to the Queen’s Rangers (Ed. Note: The Queen’s Rangers were a loyalist military unit during the Revolutionary War) upon their arrival in America. Unluckily for military science — but lucky for the fledgling country in rebellion — Ferguson was wounded before encountering Lt. Col. Simcoe (who became the next and most successful commander of the Queen’s Rangers) and Capt. Ewald, since all three were serious students of tactics. Patrick Ferguson was an inventor in addition to being a tactician.

Ewald and Simcoe made a dynamic contribution to Light Infantry tactics, and the inclusion of Ferguson’s ideas and his new breechloading rifle may have inspired seminal change. His unit was too small to be of consequence to a grand army but perfect for the small unit tactics of the Rangers, where his concepts could be assessed and refined by like-minded men. His rifle could have revolutionized warfare if employed on a grander scale, especially after being perfected by experience and with tactical theories honed with the input of men like Simcoe and Ewald.

His rifle was never improved beyond its early development, and his tactical theory never explored. It is often said the British despised riflemen, but they only despised riflemen shooting at them. They had no problem with their riflemen returning fire. Despite the noise about the British denigrating the rifle as impractical, commanders in America appreciated rifles and understood the special how and why of their use. After all, Britain brought over 4,000 Hessian riflemen — Jägers — and built 1,000 rifles for use by their own Light Infantry. Rifles were not unwelcome or misunderstood. The concept of rifle use by Light Infantry went hand in hand, and had been well appreciated since before the French & Indian War in America when commercial rifles were issued.

Applications

Captain Ferguson’s ideas centered on the rifle not only as a skirmish weapon, but one that could replace the musket as a line infantry weapon. His concept was for the line to open with accurate, aimed fire while beyond range of reply. His men could load and deliver this aimed, accurate fire from prone, too, where they were far less vulnerable to artillery.

The Ferguson rifle could be loaded prone easily unlike conventional muskets and rifles. Trained riflemen could fire up to seven shots a minute. Although aim suffers with speed, speed counts more as the opposition closes in. Ferguson personally demonstrated his shooting in front of the King at ranges out to 300 yards. He put all his shots on the 100-yard target with five in the bull’s-eye, according to eyewitnesses. All this in a rainstorm on a windy day as well!

From the rifle’s maximum range, hits from the return musketry of the smoothbore would have been an accident, and a regiment of riflemen lethal to opposing infantry, and equally hazardous to cavalry. The rifle and its two-leaf sight was capable of putting a ball on a man out to 300 yards in Ferguson’s hands. That’s a long way for an opponent to walk under fire.

Unlike conventional rifles, the Ferguson could maintain this accurate fire far longer, and as the opposition marched closer, the Ferguson’s lethality remained constant where a conventional rifle’s would decrease as it fouled, first robbing accuracy, then fouling beyond the ability of the man to load easily, and then fouling beyond the ability to load at all. Where the smoothbore could deliver 20 shots or more before fouling out, the muzzleloading rifle was lucky to reach five or seven. With properly greased balls and breech screw the Ferguson continues firing. The downside would be grease melting off the balls during hot days, and clumping together over cool nights.

The addition of a 24-inch sword bayonet increased the Ferguson-armed riflemen’s versatility. No other rifles were fitted with bayonets until the Napoleonic War when Britain added a bayonet to the P1800 Baker. It, too, mounted a sword bayonet, and it’s hard to believe the lesson of the Ferguson wasn’t used in the decision to choose that style.

Another forsaken aspect of the Ferguson’s firepower was the ability of two or three ranks to maintain continuous rapid fire from prone, kneeling and standing. A smaller unit would have the ability to engage larger ones with rapid, lethal firepower, something not practical until the metallic cartridge arrived. As skirmishers, they could make things hot for artillery, too, and well beyond range of all but artillery.

The Ferguson is safer. Muzzleloaders often have embers burning in the breech area from the previous shot unless the shooter wipes or blows down the muzzle. A subsequent load can be ignited with dire consequences to the hand at the muzzle, or detonating the horn if the shooter is unwise enough to load from one. By opening the breech the embers are quickly extinguished, and there are no combustible materials like paper to smolder. Finally, the rifle is primed after it is loaded, unlike other British arms which were primed first.

The Ferguson bayonet’s socket was made longer than the standard bayonet so the men could wrap their hand around it for use as a sword if necessary. Another aspect of the Ferguson bayonet was it was sharpened on both edges. Ferguson taught his men to slash at an opponent’s hands while fencing. Regular bayonets were thrusting weapons only. The Ferguson added slash to the thrust. The later Baker bayonet had a sword handle and guard.

Marching Orders

What remains in the records of Ferguson’s original orders isn’t very clear on the aims and goals of the exercise he wanted to pursue. In his letter to General Howe, Secretary at War Lord William Barrington vaguely states, “[Ferguson] having by Directions from the Board of Ordnance superintended the making of some Riffle Barrel pieces of a new Construction, the King has thought it proper to order that experiment should be made in the most proper manner as to their Utility.”

It’s possible Ferguson was able to explain his vision to Howe upon his arrival in America. Gen. Howe was a proponent of the Light Infantry, and Ferguson attended Howe’s school on Light Infantry in 1774, where he excelled and likely began forming many of his ideas. However, Ferguson’s Corps of 100 was such a small contingent, they mattered little in the bigger schemes of battle. They could only prove themselves working in one of the smaller units.

Howe picked the one unit where Ferguson could prove himself — under the command of Maj. Wemyss of the Queen’s Rangers (along with Capt. Ewald’s Hessian riflemen), and all engaged in the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. There, Ferguson and the Rangers acquitted themselves well and received commendation from Gen. Howe.

Brandywine is where Ferguson famously passed up a shot at Gen. George Washington accompanied by Brig. Gen. Casimir Pulaski. He eschewed shooting them in the back as they rode away, or the history of this country might be very different today. Whether it is true is open to speculation, since the story was pieced together after the battle while Ferguson was being treated for his wounds. He put two and two together hearing a description of Washington and Pulaski.

Ferguson was severely wounded — shot through the right elbow — and there the promise of the Ferguson rifle ends, as Ferguson never really recovered from his wound. He learned to write and shoot left-handed, since his right arm healed crooked (and was almost amputated). Ferguson would be killed at King’s Mountain October 7, 1780, and his rifle’s potential buried with him.

Conclusion

No real clear explanation for the dissolution of his rifle company has ever arisen. Rifle use was on the rise in the British Army. Ferguson’s men and non-commissioned officers were drawn from units posting to America along with Ferguson, and were sent back to their units upon dissolution of his company. There is evidence they took their rifles along.

Often, rifle companies were detached in squads to line infantry companies, since they could be used to cover movement with their unique ability to apply violence so much farther away. In boat landings, riflemen would be out of the boat first. (Ferguson’s Corps were among the first off the boat leading up to the Battle of Brandywine.) Off first, they could secure the beachhead and begin scouting for the enemy, key roles for light infantry.

It is very possible Howe treated them as he might any other rifle company by breaking them up into smaller groups. Many Highlander rifle companies were used this way, too. The Hessians usually moved in companies, since they had an added language barrier. Had Howe understood the unique capabilities of the rifle, it is possible he would have reacted differently. Or maybe not. There were now less than 100 of them, by design they were on loan from their original units, their officer severely wounded, and certainly no way to test the more grandiose of Ferguson’s ideas. But there was a real need for trained riflemen throughout the army, and here were 100 rifles that could do more good dispersed back to their former units than kept idle awaiting their officer’s recovery — if he recovered at all.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

56

56