American Flamethrowers in World War II

October 24th, 2023

11 minute read

Perhaps the most common phrase about flamethrower operations in the Pacific is something along these lines:

“After a couple of bursts from the flamethrower, no further resistance or activity was encountered from that position.” From “Flame”, a June 1945 U.S. Army Special Technical Intelligence Bulletin

Man-portable flamethrowers debuted during World War I, and the specialized weapon achieved tactical successes for both sides. The flamethrower capitalizes on man’s primal fear of fire, and its intimidating effect on defenders is undisputed.

[To read more on the history of these weapons, check out Flammenwefer — World War I German Flamethrowers.]

In the final equation, the flamethrower is a brutal, yet completely necessary weapon — one of the few that can dislodge a particularly stubborn opponent from a strong defensive position. But as I write this in 2023, there is very little information available about American flamethrowers and the men who used them.

First to Fire: America’s M1 Flamethrower

America entered WWII far behind in flamethrower technology. As the Marines and G.I.s fighting in the Pacific Theatre began to advance through the Solomon Islands, Japanese defenses became much more difficult to overcome.

In 1942, the only portable flamethrower available to American troops was the M1, and this was a pathetic contraption, with unreliable ignition and wonky pressurized fuel tanks, ultimately hobbled by a poor flammable mixture. With a range of no more than 15 yards (and often less than that), the M1 was disliked and distrusted by the troops.

Solving the Fuel Problem

America’s early flamethrowers used a simple gasoline mixture that burned hot enough, but the fluid was almost completely consumed just a short distance from the projector’s nozzle.

The U.S. Chemical Warfare Service began work on a slower-burning fuel and by late 1942, a better answer was developing. An early metallic soap compound was added to the fuel to create a slower-burning mix that doubled the range of the flame projector.

A new flamethrower, the M1A1, was designed to use the thickened fuel, and this was issued by the beginning of 1943. Although the M1A1 was an improvement, it was still heavy (68 pounds), and suffered from many of the drawbacks of the original M1 — most notably an unreliable ignition system for the flame wand.

Some successes were achieved with the M1A1, but the weapon and particularly its fuel were greatly inconsistent. A better solution was about a year away.

Enter Napalm

The Chemical Warfare Service continued to refine incendiary fuels throughout 1943, until “napalm” became standardized in early 1944. Napalm burns much longer than gasoline, it is easier to disperse, and it also “sticks” to most targets.

Napalm is an efficient “thickened fuel”, using an aluminum soap compound — it burns at up to 2,190 degrees Fahrenheit. While gasoline explodes into a massive bloom when ignited, napalm leaves the flamethrower as tight, dark-colored jet stream.

This extended the range of the flamethrower out to 40 yards, and allowed the flame gunner to spray the fiery, sticky mix into doorways, windows, bunker viewports and gun slits. Napalm quickly became the incendiary fuel for US fire bombs and flamethrowers, both man-portable and vehicle-mounted.

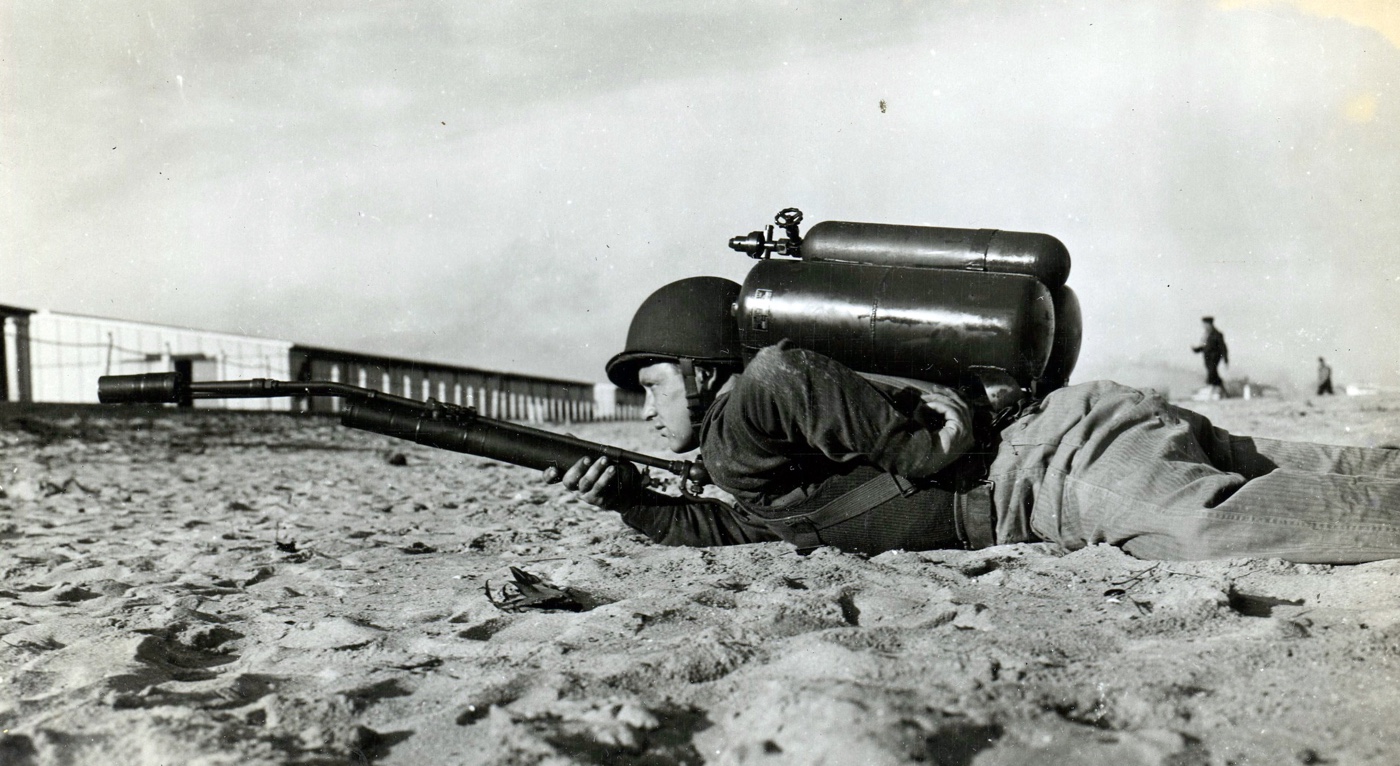

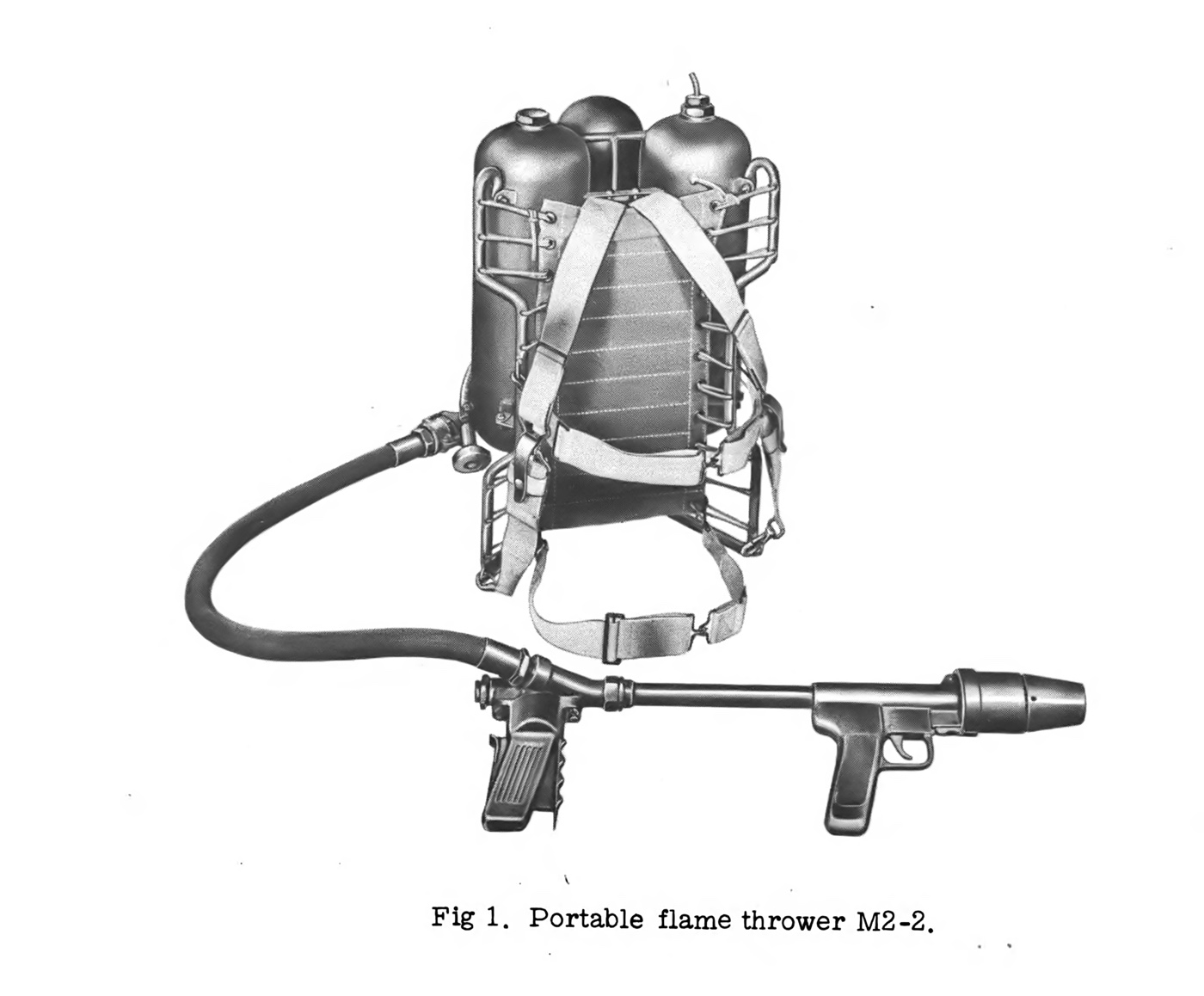

Along with napalm, American troops received a new flamethrower in the summer of 1944. This was the backpack frame-mounted M2-2. It was still heavy (68 pounds loaded weight) but it offered reliable fuel ignition with much greater range and user safety.

By the time that the U.S. Marines were hitting the beaches of Guam and Peleliu, the M2-2 was ready to get Japanese defenders out of their caves and bunkers. When the U.S. Army landed in the Philippines in late October, the G.I.s were equipped with it, too. The M2 flamethrower would quietly become one of the most important weapons in the U.S. arsenal in the last year of the war.

Training Was Essential

The U.S. Army pamphlet “Flame” (issued in June 1945) makes special mention that training, beyond all other factors, is critical for the success of flamethrower operations.

“The flamethrower operator and his assistant must be thoroughly trained in the operation and maintenance of his weapon, and must be fully aware of its capabilities and limitations. Moreover, other members of the unit must also be familiar with flame action, and officers must know in advance where and how to employ it. Both AGF and CWS consider that comparative failure of flame in ETO and MTO was as much due to lack of training, and lack of understanding of its employment, as to terrain and technical difficulties. Heavy casualties among flamethrower operators in early Pacific operations may be traced directly to these factors.”

The pamphlet also advises that in preparing for flamethrower operations, a thorough reconnaissance of the target is necessary before the assault:

“The flamethrower is limited in its ability to keep a target under fire; once the tank is empty, the operator must retire. Unless he knows the exact position of the target, and the exact location of the portion of the target he is to flame, he will only waste fuel and perhaps his life as well. It is the responsibility of those who have located the target to give full information to the flamethrower team. This is particularly true in the Pacific, where targets may not be seen even from a few feet away.”

The flame gunners became critical targets for Japanese snipers and MG teams. To protect the flamethrower during the assault, the Army recommended an abundance of suppressing fire on the target.

“The third requisite of a successful flamethrower assault is continuous fire support. The defenders must he driven underground; fire may remove obstacles and rip away camouflage rendering the flame-man’s task that much easier. Support may come from the rifle and BAR fire of the assault squad itself; it may be HE and WP fire from infantry or chemical mortars; it may be infantry cannon, tank destroyer or howitzer fire, or it may even be from the air. Whatever its source, it must be maintained until the flamethrower team is in position. Once support fire ceases, and before the flame trigger is pressed, the flame-man is a vulnerable and profitable target.”

By early 1945, the Marines created assault groups to neutralize Japanese fortifications, combining fire-suppression teams (with BARs for longer-range work and including Thompson SMGs for short-range security), flamethrowers and demolition teams. Once the defenders were neutralized by flame, the demolitions team would destroy the bunker, or seal the cave with explosives. By the time of the Okinawa campaign, these tactics became known as “Corkscrew and Blowtorch”.

M2 Flamethrower in Combat

While there isn’t a wealth of combat reports available concerning flamethrower use during World War II, I was able to find matter-of-fact descriptions from the 4th Marine Division during their actions on Iwo Jima. There had been high hopes for the flamethrowers mounted in M4A3 tanks (sometimes called “Zippos”), but the terrain on Iwo Jima frequently prevented the tanks from getting into an effective firing position.

Some reports note that the range of the tank-mounted flamethrowers was also much lower than expected. Ultimately, it fell to the Marine assault groups, and the individual flame gunners to attack the Japanese cave and bunker complexes.

“The portable flamethrowers, attached to frontline companies, when the need arose, were used extensively on caves and Pillboxes with good results. Re-supply presented a problem in that there were times when sufficient servicing and supply personnel were lacking in order that the flamethrowers could be kept in action continually for several hours at a time.”

The M2 flamethrower was a specialized weapon, and some Marine commanders felt it was best employed in the hands of assault experts:

“The flamethrower proved to be an effective weapon against caves, however, its short range limited its use. It. is not necessary to have a flamethrower with the rifle company at all tImes. A rifle company is more efficient without the burden of refueling and maintaining the flamethrowers. Also the flame thrower is too heavy to be carried every place that the rifle company goes. For those reasons the assault platoon under battalion control proved extremely effective. Companies called for the flamethrowers when they needed and after a mission was completed the flamethrower and operator returned to battalion.”

The process of busting bunkers and flushing out caves was grueling and dangerous. This entry from March 1, 1945, shows there was no other way to get the job done but the hard way:

“Hill 382 was honeycombed with caves with many open entrances. Many enemy personnel are still in the labyrinth-like system of caves, network of small passageways, and miniature canyons. During the reconnaissance, and very late in the afternoon, hand grenade fights were in progress, and the assault squads were still blowing cave entrances and using flame throwers on points of resistance…Consequently, Infantry employing demolitions, portable flamethrowers, and small arms together with bazookas, smoke and fragmentation hand grenades, had to maneuver into position with small groups and destroy the positions. This was a slow, prodigious, and tedious process, which required able leadership on the part of squad and group leaders, a number of whom were killed or wounded and evacuated while taking this exceedingly well fortified and hazardous ground.”

On Wake Island in Dutch New Guinea during May 1944, a U.S. Army flame gunner found that the fear of his weapon was enough to break even the most hardened Japanese defender. An Army report describes:

“Another flamethrower operator wiped out a three-pillbox position on Wakde that had resisted a large combat patrol and tank fire. While the patrol pointed out the camouflaged targets with tracers, the flame-man crawled through dense underbrush and sent a two-second burst through a side port. It fell silent. He crawled to the center position and put a four-second burst into the front embrasure; it, too, was silenced. Although he had but a little fuel left, he crawled to within 10 yards of the remaining pillbox and pulled the trigger. His flame sputtered and fell short, but the single Jap machine gunner had not waited; he killed himself.”

Using the M2 Flamethrower

While it is unlikely that our readers will find themselves using an M2 flamethrower, I pulled together some guidance from the U.S. Army field manual “Combat Flame Operations” from July 1970.

Firing Procedure for the M2A1

Before beginning a flame mission, insure that the carrier is adjusted so that the tank group will ride as comfortably as possible on your back. Check to see that the lacing which holds the carrier to the tank group is tight enough to keep the metal tank group from irritating your back. Adjust the shoulder straps so that the tank group rides high, but not so tight that they restrict blood circulation in your arms. The body strap should be tight enough to prevent the tank group from bouncing excessively when you run.

Controlling the ignition

Fuel ignition is controlled by the ignition lever on the M7 gun group, you cannot depress the ignition lever unless you depress the ignition safety lever at the same time. Several techniques are used to ignite the fuel.

You may desire to coat the target with fuel before you ignite it. In this case, first depress the fuel valve lever, allowing the un-ignited fuel to go to the target. Then ignite the fuel by firing an ignited burst at the target. Normally, you will depress the ignition lever first and then the fuel valve lever one or two seconds later to ignite and project the fuel to the target.

There are five charges in the ignition cylinder. Each of these charges will burn for 8 to 12 seconds. In very cold weather or when using a poor grade of fuel, it may be necessary to use two or more charges at the same time in order to ignite the fuel. This can be accomplished by depressing the ignition lever, releasing it, and depressing it again for each additional charge which the gunner wishes to fire from the ignition cylinder.

The fuel is controlled by the fuel valve lever. In order to operate this lever, depress the valve safety lever at the same time. The ignition grip of the M7 gun group can be rotated and adjusted to suit the gunner. Be sure to depress the fuel valve lever all the way or else the fuel may not escape from the gun with sufficient force to reach the target. Release the fuel valve lever as soon as the fuel is exhausted. You can tell when the fuel is exhausted by a definite change of sound.

Gunnery Fundamentals

The point of attack from which flame will be discharged against the target should be indicated on the ground to the flamethrower gunner. Three fundamental gunnery techniques involved in successful flame efforts, especially against point targets, are as follows:

a. Initially the flame rod should be fired onto the top of the target and immediately depressed into the target. By being over the target with the first burst, the gunner is assured he is within range, and the target is not temporarily obscured for well-sighted and rapid subsequent bursts.

A short burst may cause the firer to believe he is on the target because the billow of flame at the point of impact may obscure the target.

b. Once on the target, the gunner should use sufficient flame to accomplish the mission within limitations of the weapon. He may fire one long continuous burst or short bursts, at his discretion.

c. Bursts should be delivered from a stationary position. Movement decreases accuracy and endangers the flamethrower gunner. Fire, vapor and unburned fuel may blow back toward the gunner when he is advancing rapidly and firing un-thickened fuel.

Accuracy

Flame can be fired with accuracy through small apertures. The degree of accuracy required depends upon the target. For lethal effect against personnel in the open or in well-ventilated fortifications, flame must be directed with a high degree of accuracy. Personnel in a poorly ventilated enclosure may be subjected to a general blanketing with no particular regard for pinpoint accuracy, and casualties may be expected.

Since the element of surprise should normally accompany the use of the flamethrower, this weapon should not be used against individuals who can be destroyed by other weapons; this use wastes fuel and unnecessarily reveals the position of the flame gunner.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

100

100