American War Dogs of World War II

July 12th, 2022

11 minute read

Even though my wife and I are fully prepared to defend ourselves and our home with firearms, our first line of defense and our early warning system is our Tibetan Mastiff. He detects even the faintest sound and the slightest motion that is out of place. Those sentry skills are simply the manifestation of his natural instincts, and he uses them to happily watch over us every day. I couldn’t ask for more from any friend or relative, human or canine.

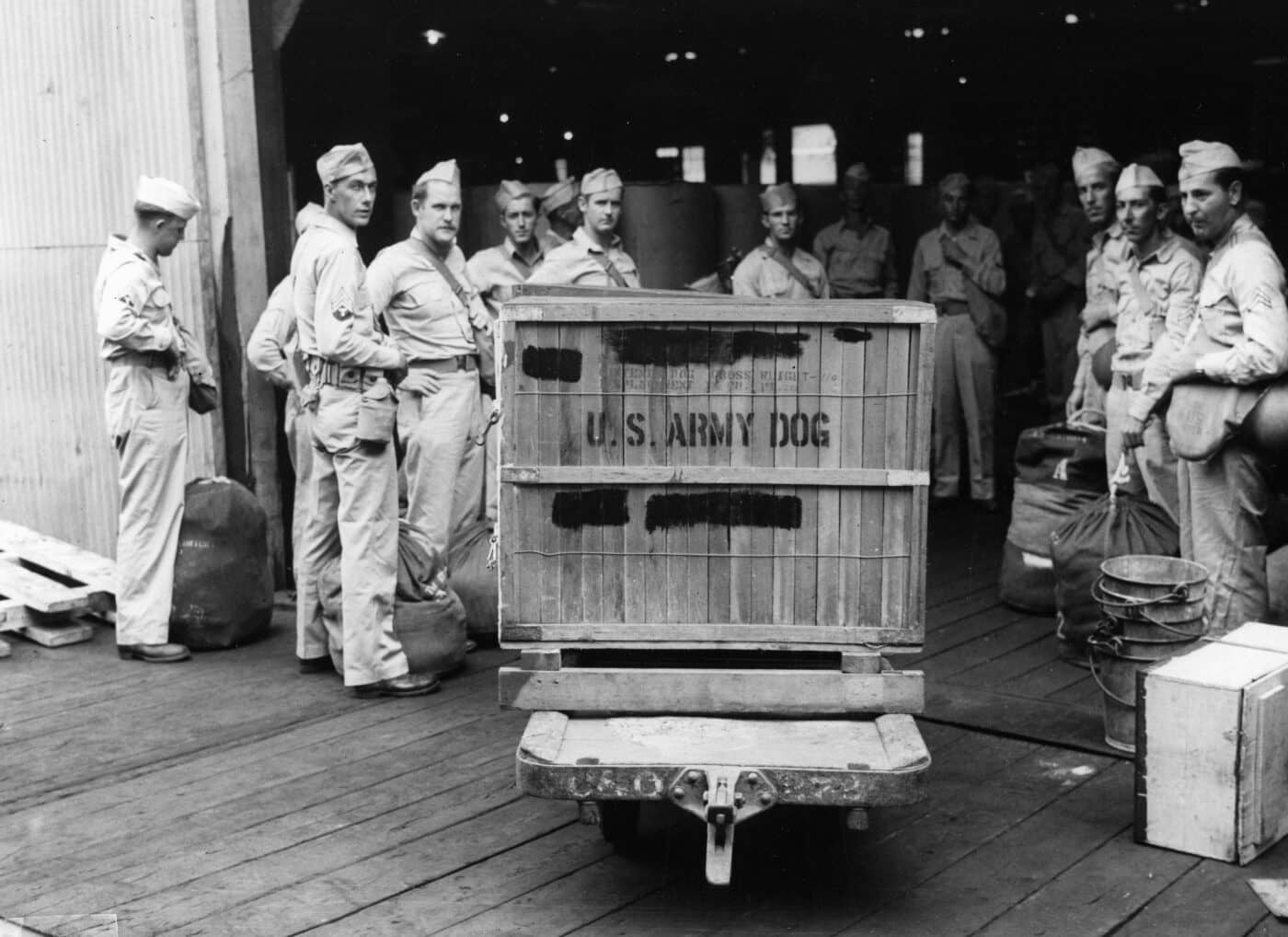

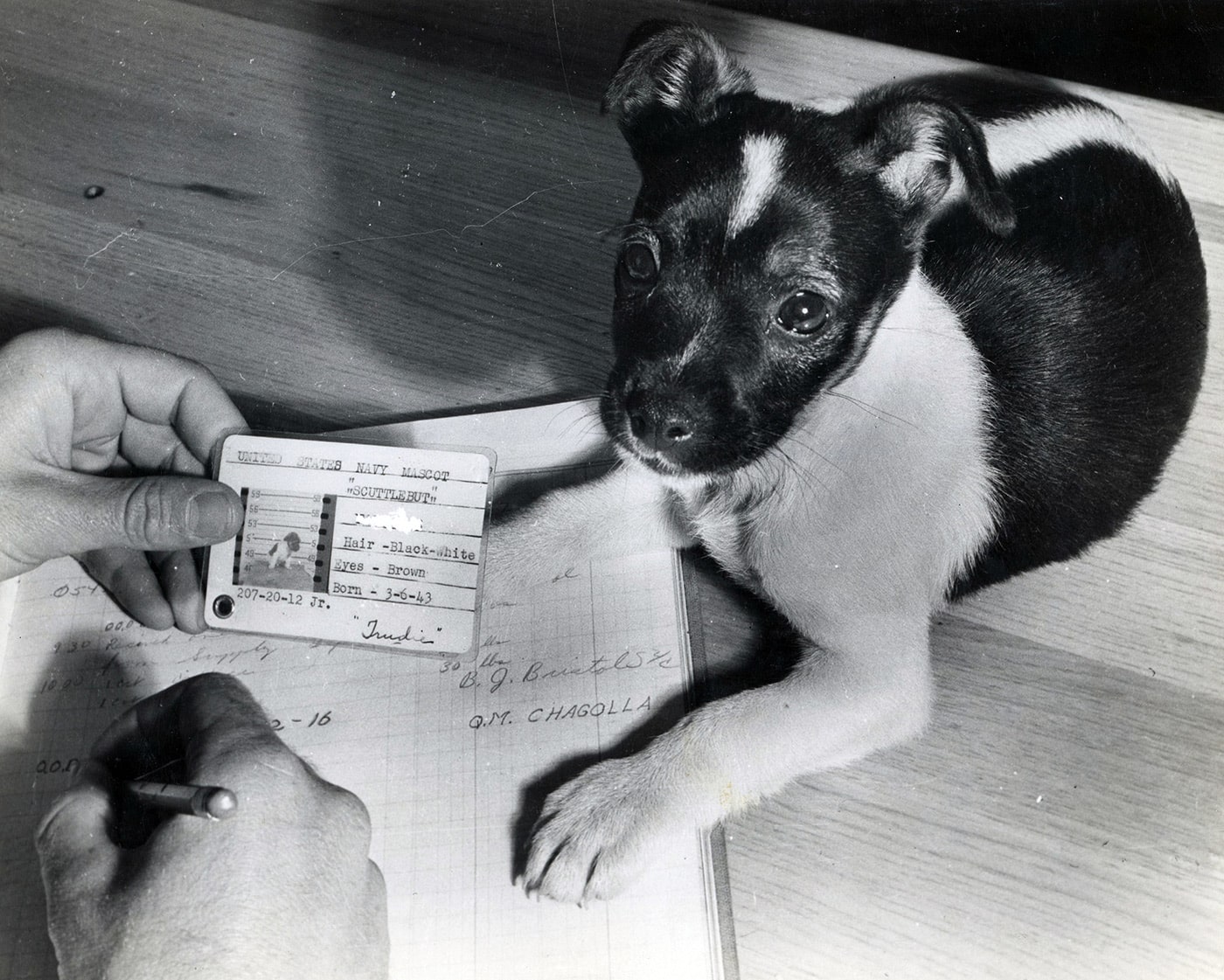

During World War II, America’s armed forces quickly realized the nation needed as much help as it could get. To assist our fighting forces overseas, along with those defending our shores and vital installations stateside, American dogs were brought into the Army, Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard.

Dogs had been used by military formations for hundreds, if not thousands of years. In the 20th century, uses focused primarily on sentry/security functions, along with messenger duties, while some of the larger breeds were used to pull small “dog-carts”. The French and Belgian armies had often used dogs to tow machine gun carts in World War I.

Soviet Cruelty: Dog Mines

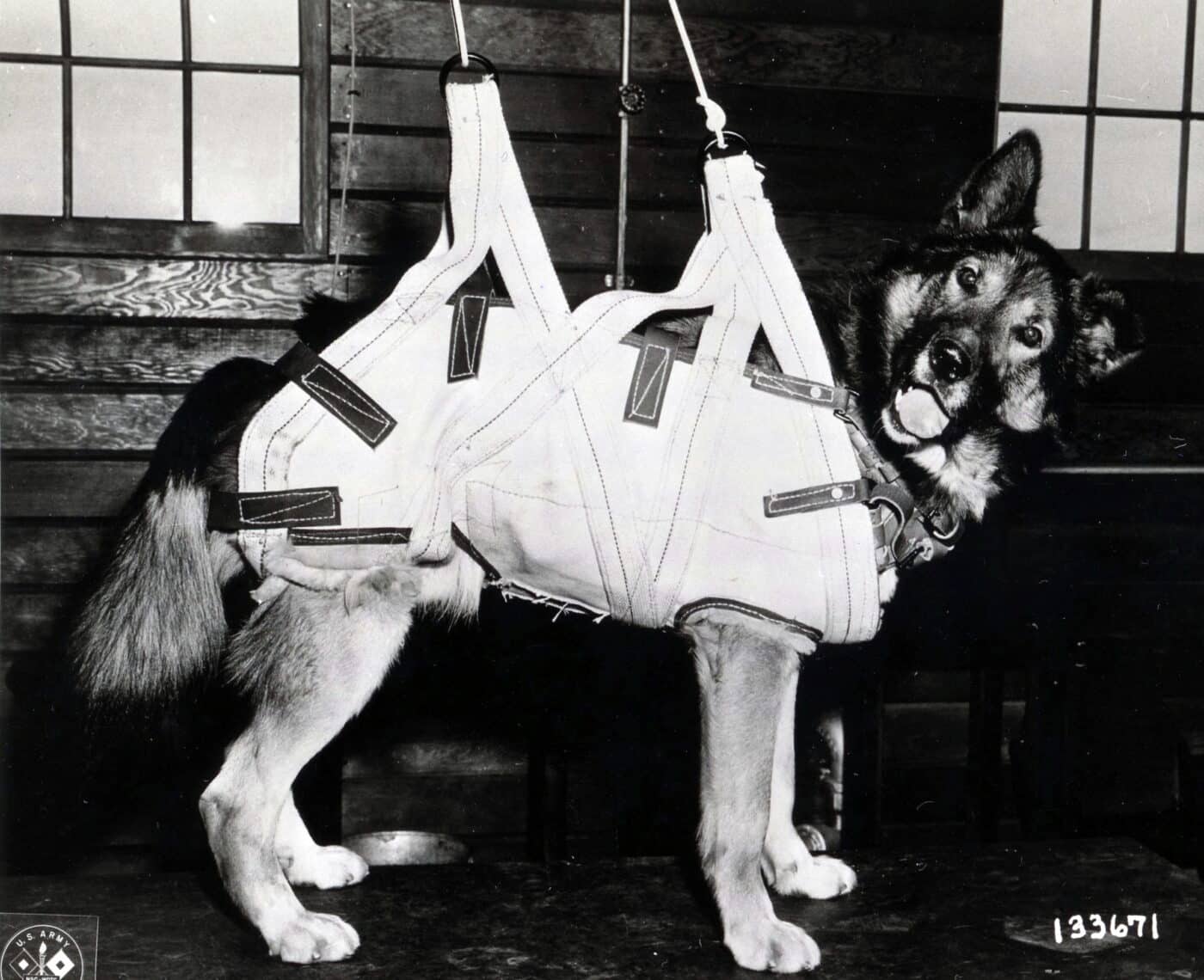

By the time America entered World War II, dogs were back at war again around the globe, in mostly familiar roles. In the desperate days of 1941 and early 1942, the Soviet Red Army attempted to use dogs as anti-tank mines. The dogs were fed exclusively underneath tanks, and then after a bit of starving, the canines had a large explosive with a tall detonating striker strapped to their backs.

Released on the battlefield, it was hoped they would run under German tanks and explode their charges where the armor was the thinnest. Unfortunately, the dogs could not distinguish between German and Soviet tanks, and it was anyone’s guess where a confused, hungry dog would go on a noisy, smoky battleground. The practice was soon abandoned.

American Dog Volunteers

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the U.S. Army had few dogs in service, save for a handful of police dogs and a few teams of “Alaskan” sled dogs. American dog owners quickly stepped in to help and formed “Dogs for Defense, Inc” (DFD). Dogs for Defense secured the endorsement of the American Kennel Club and provided a way for Americans to donate their dogs to the U.S. Army Quartermaster General’s Plant Protection Branch.

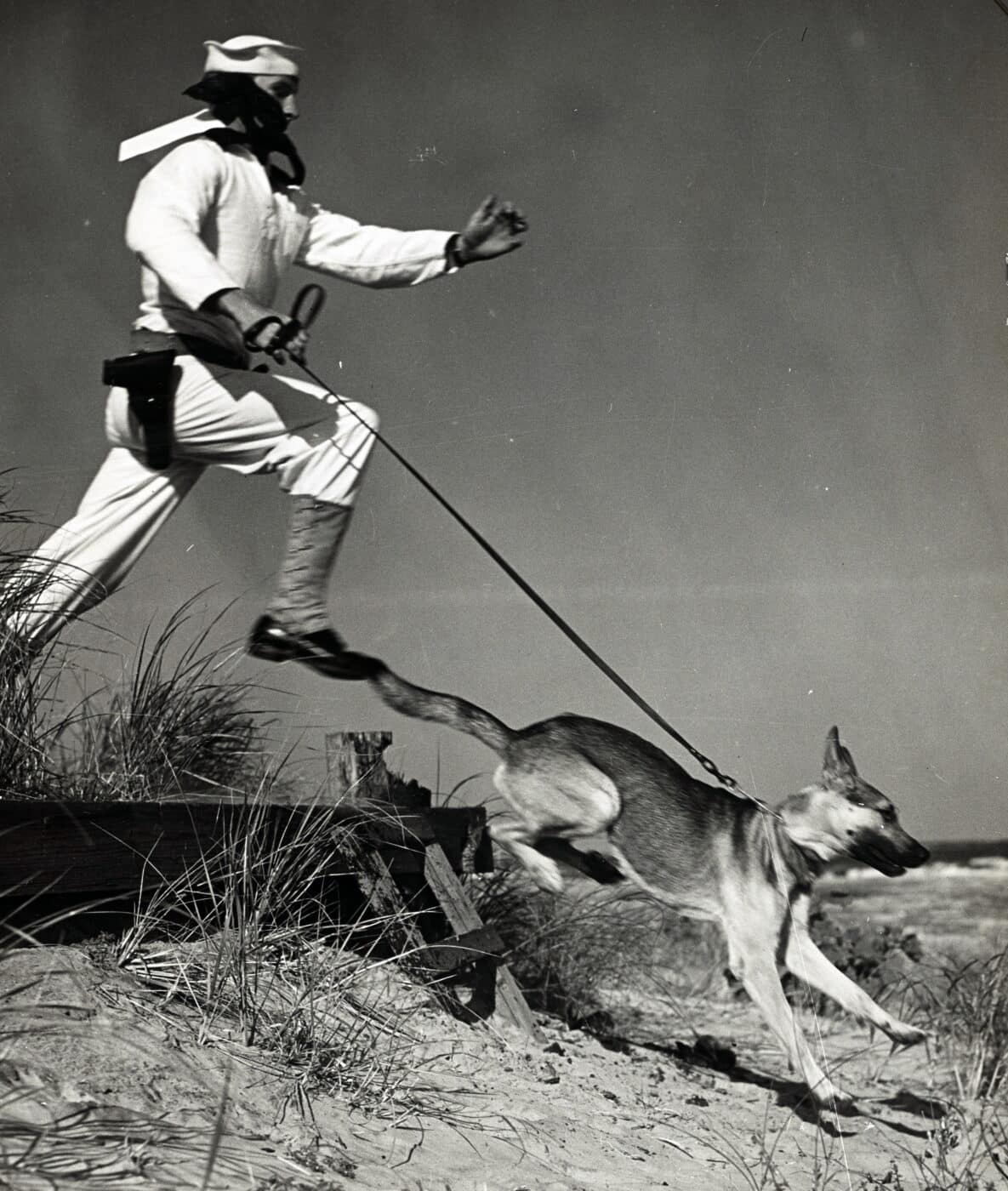

The dogs received an abbreviated, ad hoc training to work with security teams at U.S. production facilities to protect against saboteurs. Some of the dogs were also used in coastal and beach patrols.

While the DFD civilian volunteers meant well, their trainers had varying levels of experience, and the consistency of the dogs’ performance suffered. Also, a wide range of dogs was accepted into the early program, and some of the breeds were not up to the task.

By July 1942, the Secretary of War had assigned the responsibility of procuring and training U.S. Army dogs to the Remount Branch of the Quartermaster Corps.

Professional Canine Corps

Over time, the dog training program confined the dog breeds to a tight group that best met Army requirements: German Shepherd, Doberman Pinscher, Belgian Shepherd, Collie, Siberian Husky, Malamute and the Eskimo Dog. The Army also began to expand its ideas of how to use the dogs, growing beyond just stateside security duties and preparing the canines for aggressive patrolling and scouting in the overseas combat zones. American dogs were going to take the fight to the Axis.

The Army conducted several experiments with war dogs, notably as mine detectors, and an attempt to create hunter/killer packs to seek out and attack Japanese troops. Initial tests in mine detecting showed great promise, but the results achieved in the controlled environment of the testing ground proved misleading. The dogs were quickly confused on the chaotic battlefield.

The same held true for the packs of killer attack dogs — intended to be used without handlers, a pack of dogs with murdering humans on their minds were not able to distinguish between Japanese and Americans once set loose. It was determined that dog handlers were an absolute must and the “attack pack” concept did not progress beyond a rather painful testing.

Dogs in War

U.S. Army dogs saw the greatest amount of combat in the Pacific Theatre, but the Army’s most celebrated War Dog saw service in the Italian campaign.

On July 10, 1943, “Chips”, a German Shepherd mix serving with the 3rd Infantry Division, hit the beach during the invasion of Sicily. Working with his handler, Private John Rowell, Chips discovered an Italian machine gun bunker, hidden in the landing zone.

When the MG opened fire, Chips charged forward to attack. Within moments the gun stopped firing and one of the crew staggered out of the bunker with Chips at his throat. Private Rowell reported:

“There was an awful lot of noise and the firing stopped. Then I saw one soldier come out of the door with Chips at his throat. I called him off before he could kill the man.”

Witnessing this, the rest of the gun surrendered. Chips was wounded in this action, suffering several cuts and powder burns.

Three months later, in recognition of his heroism, the HQ of the 3rd Infantry Division issued a citation for Chips (officially, Chips, 11-A, U.S. Army Dog) to receive the Silver Star. Later, he was also awarded the Purple Heart.

Despite the GI’s heartfelt appreciation of Chips’ work, Army regulations reared their ugly head and prohibited these awards, ultimately forcing them to be rescinded. Regardless, Chips continued to serve throughout the war in Europe and was eventually discharged to his pre-war owners in December 1945. He came home to a hero’s welcome, fit for any American combat veteran.

Marine Corps Devil Dogs

In the summer of 1942, the U.S. Marine Corps decided to add dogs to their arsenal, with a focus on using the canines as the “point man” in jungle patrols. This concept can be traced back to the USMC manual “Small Wars Operations”, revised in 1935.

Marine experience with trained dogs in the jungles of Haiti and Nicaragua was reflected in the comment: “Dogs have been employed to indicate the presence of a hidden enemy, particularly ambushes.” The Marines planned to use the canine’s natural skills to give Leatherneck patrols an early warning system against a Japanese opponent who was highly skilled in jungle camouflage.

The Marine Corps received dogs from several sources, ranging from Dogs for Defense, the Doberman Pinscher Club of America, and from many individuals who offered their canines directly to the USMC.

During WWII, the Marines normally trained their dogs for one of two assignments: scout dogs or messenger dogs. Scout dogs were involved in aggressive patrolling and reconnaissance. Messenger dogs were trained to carry communications between two handlers over several miles. Throughout their training, both types of USMC war dogs were regularly exposed to the sounds of gunfire and explosions.

A well-trained handler is just as important as a well-trained dog. The following description of the training of Marine dog handlers comes from a USMC report on war dogs, via the Marine Corps History Division:

“The handlers were selected for their intelligence, character, and physical ability as well as previous training as scout-snipers without dogs. When such men were not available, they had to be trained as scout-snipers concurrently with the dog handling. Since dogs, from the point of view of training, can only respond successfully over limited periods, it was possible to spend half the time of the men training dogs, and half the time training the men as scout-snipers. Paradoxically enough, the dog on duty could out-class a man in alertness, lack of sleep, and in general condition, but in learning his lessons it was found necessary to give frequent breaks and not spend too many hours a day on the lessons. Previous experience as a dog handler was not a prerequisite, but men who had associated with animals and had that indefinable ability to read their minds and understand them, were the most successful.

“A high percentage of the best handlers came from farms where they had handled hunting dogs and farm stock. There was no known means of compelling a man to be an expert dog handler. Some men soon learned that they were not war dog men and were immediately transferred to other duty. In the same way, the dogs who demonstrated that they did not have the qualities to be a war dog in the Marine Corps were returned to their former owners.”

Dogs During the Bougainville Campaign

The first Marine Corps dog unit that went into action was the 1st Marine War Dog Platoon, that landing on Bougainville in November 1943, attached to the 2d Marine Raider Regiment (Provisional).

The Marine Raiders were enthusiastic about the war dogs, and their commanding officer commented in his report after the Bougainville campaign:

“The War Dog Platoon had proven itself to be an unqualified success and the use of dogs in combat was on trial. This first Marine War Dog Platoon was admittedly an experimental unit and minor defects were found that need to be remedied. But the latent possibilities of combat dog units proved itself beyond any doubt.”

The following examples are a few of those cited of the war dogs’ exploits in the Bougainville after-action report:

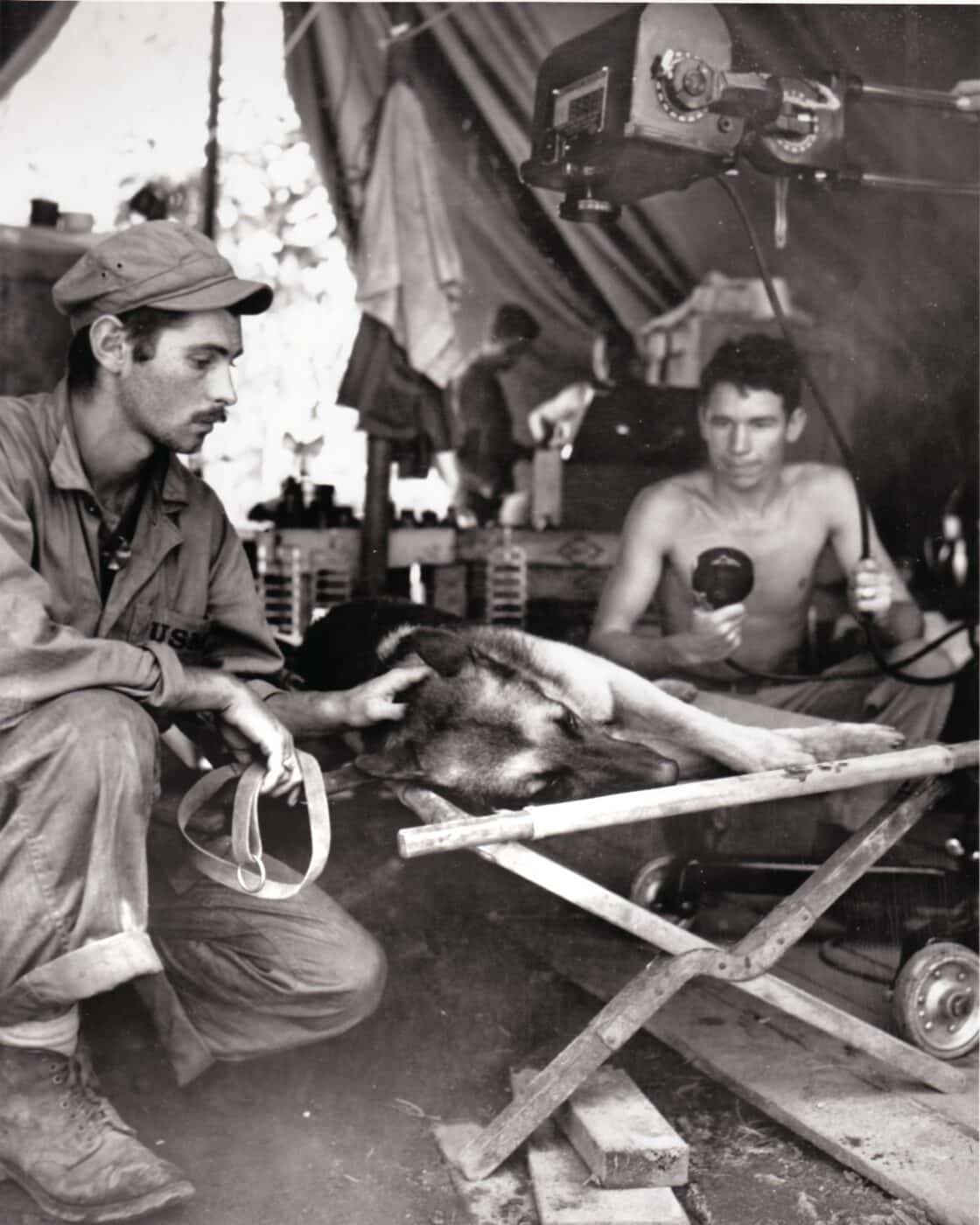

“On D-day Caesar (a German Shepherd) was the only means of communication between M Co. and Second Battalion CP, carrying messages, overlays, and captured Jap papers. On D-day Plus 1, ‘M’ Company’s telephone lines were out, and Caesar was again the only means of communication. Caesar was wounded on the morning of D plus 2 and had to be carried back to Regimental CP on a stretcher, but he had already established himself as a hero.

“Otto (a Doberman Pinscher) on D plus 1 while working ahead of the point of a reconnaissance patrol, alerted the position of a machine gun nest and the patrol had time to take cover with no casualties when the machine gun began firing. Otto alerted the position at least one hundred yards away.

“On D plus 6 Jack (a German Shepherd) was shot in the back but even though wounded carried the message back from the company about the roadblock that the Japs had struck and sent stretcher bearers immediately. This was a vital message because the telephone lines had been cut. One of Jack’s handlers was wounded at the same time and thus Jack was the means of bringing help to his master.

“During the night of D plus 7 Jack (a Doberman Pinscher) frequently alerted a tree near the ‘M’ Company CP. When it became light enough in the morning Jack’s handler pointed out the tree to a BAR man near him. A Jap sniper was shot down out of the tree. This sniper was in position to do real damage in the company C.P., but due to Jack, the sniper was eliminated.”

Conclusion

The names of American heroes in World War II creates a remarkable list. Among those names you can find the monikers of many war dogs. Most of them began their lives as pets, and then found themselves willingly fighting alongside their handlers in a war that only men could start and wage. As we honor our WWII veterans, so few of them remaining now, take a moment to remember our four-legged warriors, heroes without medals, and our friends for life.

FAQ on Military Service Dogs

The U.S. Army’s dog training program confined the dog breeds to: German Shepherd, Doberman Pinscher, Belgian Shepherd, Collie, Siberian Husky, Malamute and the Eskimo Dog. Initially, nearly any breed was considered, but most proved unsuited to the work.

Most of the major powers used canines to some extent during World War II. In addition to the United States, the Soviet Union, United Kingdom, Japan and Germany all used significant numbers of dogs during the war.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

409

409