Pedersen Device – America’s Secret Infantry Weapon of World War I

November 3rd, 2020

7 minute read

In this article, writer and historian Tom Laemlein gives us the history of the famous Pedersen Device. An ingenious modification for M1903 Springfield rifle, this top secret invention turned bolt-action rifles into semi-automatic rifles that spit bullets from the unmodified gun barrel as rapidly as the soldier could pull the trigger. Fed from a 40-round detachable box magazine, the Pedersen Device substantially increased the volume of fire a soldier could put on enemy positions.

Some 60,000 of the devices were made – along with ammunition, magazines and modified rifles – for the United States Army. However, they did not arrive to the Western Front in time to give the American doughboys any use in the field. Prototypes were also made for the M1917 Enfield and Mosin-Nagant rifles that were in U.S. service at the time. Read on to get the full story of this amazing device developed by John Pedersen.

“Mr. Pedersen started his demonstration by firing the Springfield rifle he brought with him. After firing a few shots in the ordinary way, he suddenly jerked the bolt out of the rifle and dropped it in a pouch which he had with him, and from a long scabbard which was on his belt he produced a mysterious looking piece of mechanism which he quickly slid into the rifle in place of the bolt, locking the device to the rifle by turning a catch provided for the purpose. Then he snapped into place a long black magazine containing forty small pistol sized cartridges whose bullets were however of the right diameter to fit the barrel of the rifle. All of this was done in an instant and in another instant Mr. Pedersen was pulling the trigger of the rifle time after time as fast as he could work his finger, and each time he pulled the trigger the rifle fired a shot, threw out the empty cartridge and reloaded itself.”

– A post-WWI Army Ordnance Magazine recounting of the secret October 8, 1917 demonstration of the Pedersen Device at the Congress Heights rifle range — via Bruce N. Canfield’s U.S. Infantry Weapons of the First World War.

Pedersen Device – Remarkable Firearm Adaptation

It was a James Bond secret weapon moment, except it happened in October 1917. The role of “Q” was played by John Pedersen, a talented firearms designer. The rest of the cast at the Congress Heights range, including General Crozier, the Chief of Ordnance, along with other officers and select congressmen, were appropriately amazed by the standard bolt-action rifle turned into a semi-automatic within a matter of seconds.

It was an invention indicative of the fertile minds of the time. John Pedersen joined the likes of John Moses Browning (M1911 pistol, BAR, M1917 machine gun) in contributing highly innovative firearms designs to America’s war effort in World War I. Previously isolationist, the United States of America joined the Allies and quickly rose to international superpower status in weapons development.

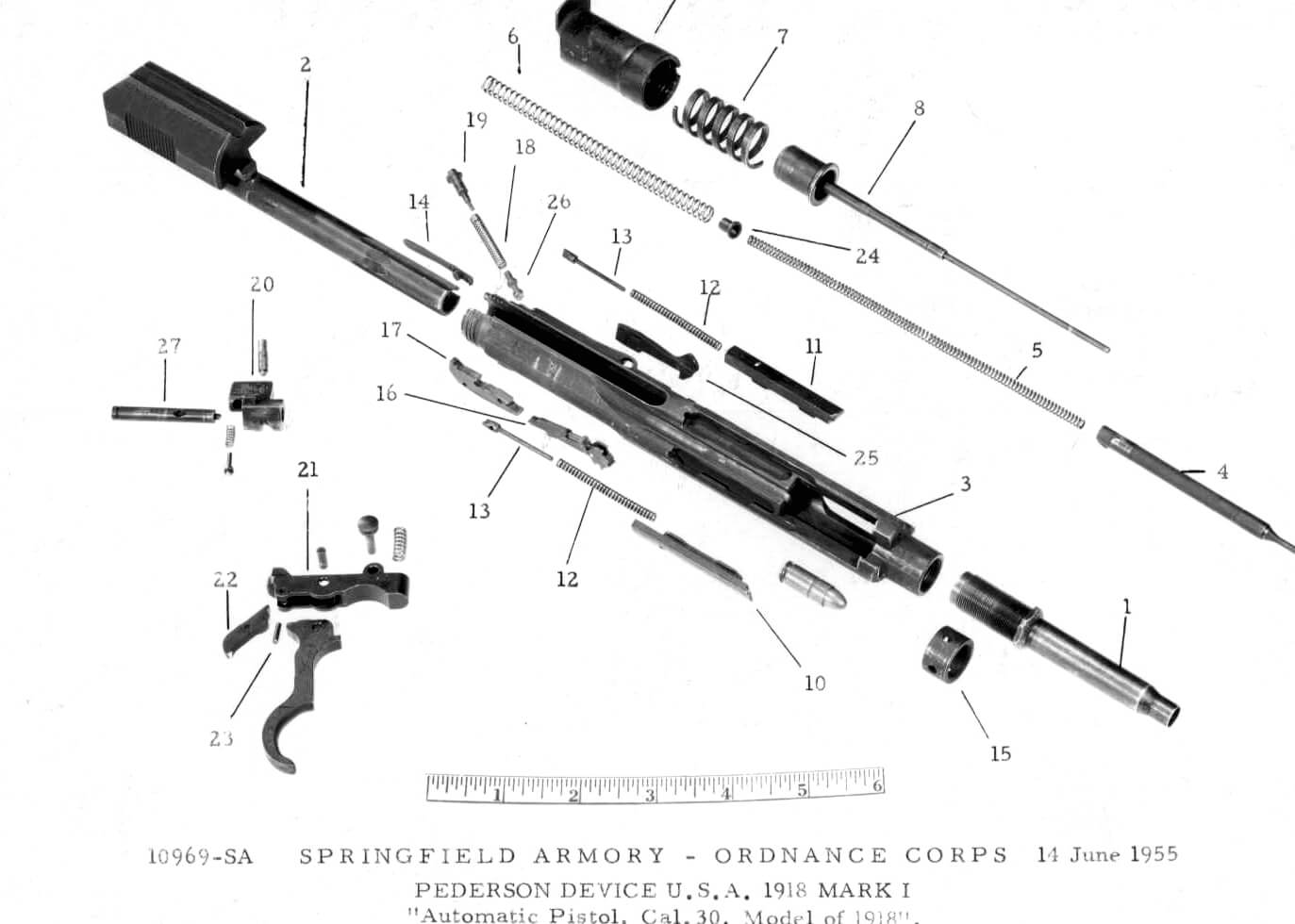

Automatic Pistol, Caliber .30, Model of 1918

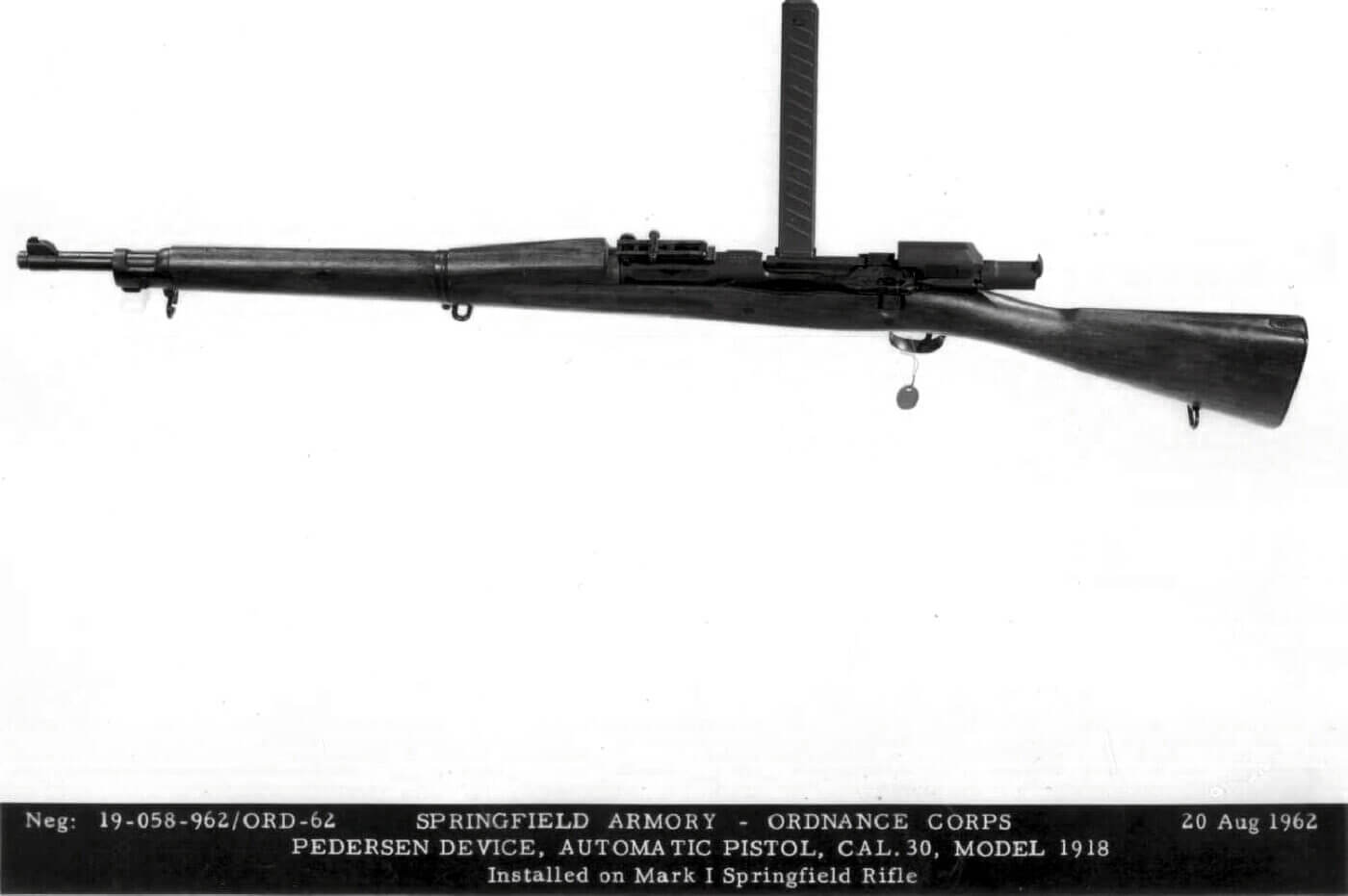

Pedersen’s unique design, fitting snugly within a slightly modified M1903 rifle (the Springfield Mark I) quickly impressed all the right people. After the secret demonstration on October 8, 1917, assessments of the new device quickly moved up the chain of command. By December, General Pershing declared that he strongly approved, and requested 100,000 of the Pedersen Devices, along with 5,000 rounds per gun. Pershing also urged “great secrecy” around the project.

In a form of “hide-in-plain-sight” nomenclature, the Ordnance Department named Pedersen’s invention the “Automatic Pistol, Caliber .30, Model of 1918”. After it was adopted, the War Department even took a good amount of criticism for adopting a .30 caliber pistol after all the recent wrangling to design and adopt the .45 caliber M1911 pistol.

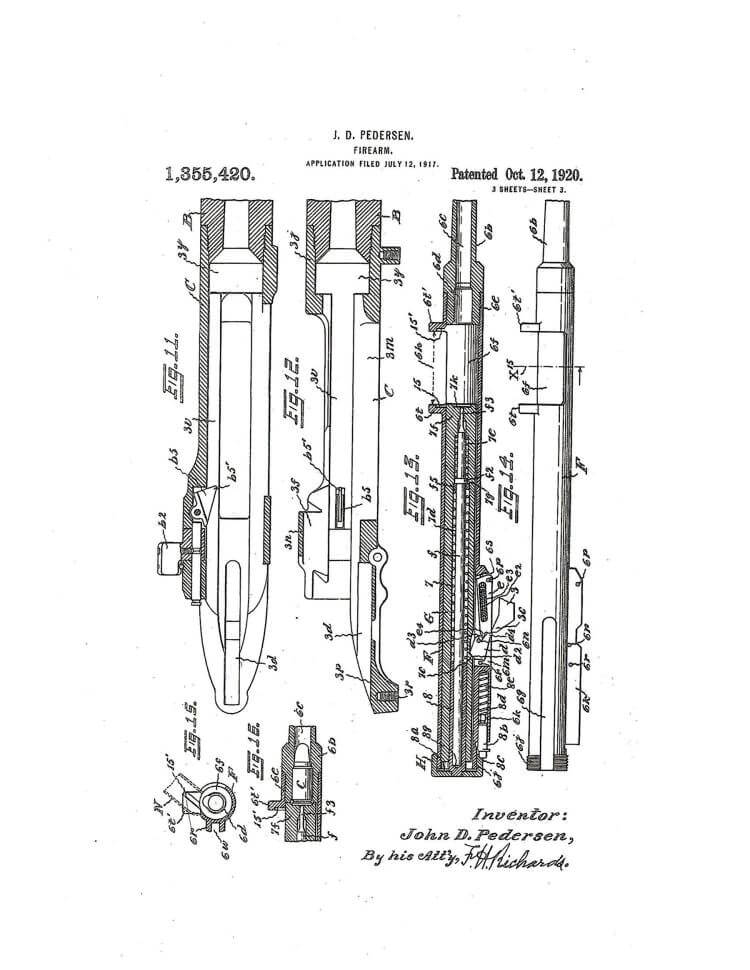

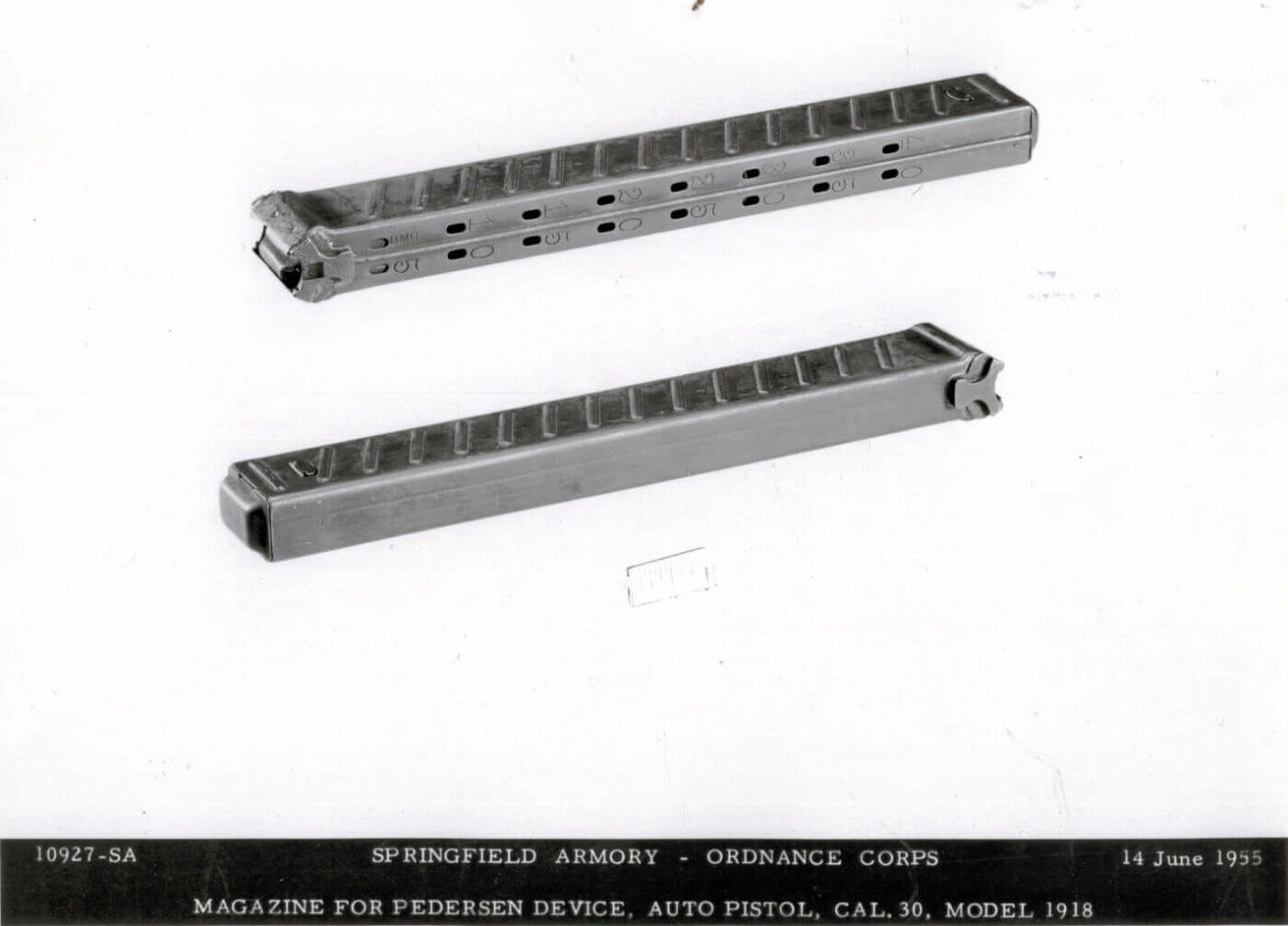

The naming ruse worked for intel purposes, but it was also functionally correct. The Pedersen Device was a semi-automatic blowback pistol, chambered for the relatively low-powered .30-18 ammunition, carried in 40-round magazines. The magazines featured cut-outs that allowed the firer to see the number of rounds remaining.

Pedersen’s goal was to provide the average infantryman with significantly more firepower, and his top-secret device was a unique way to address that important issue. The Army’s expectations were that it would allow an infantryman to convert their bolt-action M1903 rifle into a semi-automatic rifle in less than 20 seconds.

Assumptions were made that Pedersen’s weapon would be highly effective in both defensive and offensive operations. But in late 1917, America’s military was still novice, and certain concepts that appeared useful on training grounds in the USA (like “walking fire”) would quickly prove valueless on the battlefields of France. Another factor that is rarely mentioned in discussing the Pedersen Device, was that the device with two pouches worth of loaded 40-round magazines added 14 lbs. to an infantryman’s already heavy burden.

Production of the Pedersen Device (and its ammunition) began in March 1918. For compensation, Pedersen received $50K from the government for the rights to produce it and a 50 cent royalty for every one manufactured.

The Springfield Mark I Rifle

With all the attention paid to the Pedersen Device, the “U.S Rifle, Caliber .30, Model of 1903, Mark I” is often overlooked. Without the Mark I rifle, the Pedersen Device has nowhere to work. It has all the functionality of the standard M1903 rifle, with an ejection port milled into the left side, and the stock had a slight inlet added to accommodate it. Appropriate changes were made to the trigger, magazine cut-off and the sear to accept and fire the Pedersen Device. “Mark I” appears on the receiver. Minus the Pedersen Device, the Springfield Mark I operates as a normal M1903 rifle.

Although production of the device started in March 1918, finished Mark I rifles did not come off the production line at Springfield Armory until late in the year, most of them after World War I ended. When the contract for the Pedersen Device and the Mark I rifle was cancelled on March 1, 1919, 65,000 devices (along with 1.6 million magazines) had been produced. More than 65 million .30-18 cartridges were made at Remington and 101,775 Mark I rifles were made at Springfield.

Pedersen’s concept was also considered for America’s most numerous battle rifle during World War I, the M1917 “Enfield”. The “Mark II” Pedersen Device was developed for the M1917, and a similar design was also considered for the Mosin-Nagant rifle which was made at Remington on a Russian contract. Neither one went into production.

Born in Secrecy, Destroyed in Obscurity

Ultimately, the Pedersen Device never saw combat. The Great War ended in November 1918, and the Allied “Grand Offensive” of 1919 was nothing more than markings on a map. Some American forces remained in Europe for occupation duty in Germany, but most troops returned to the United States and normalcy. Even famous American weapons, like the Browning Automatic Rifle and the Browning M1917 machine gun, only saw a few weeks of service in the closing months of the Great War. The Pedersen Devices, already shrouded in secrecy, were placed into storage.

During the 1920s, U.S. Ordnance began to explore semi-automatic rifle designs, and John Pedersen’s fertile mind developed a weapon (chambered in .276, or 7mm) that would lose out to John Garand’s rifle design, the M1.

When the Pedersen Devices were declared surplus in 1931, they were not made available to the public (as they would be useless without the Springfield Mark I rifles), and nearly all the devices, magazines and ammunition were destroyed. Less than one hundred examples survived. Even so, John Pedersen’s unique genius remains, a testament to what American ingenuity can create.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

248

248