America’s Unknown Gunner Aces of World War II

June 21st, 2022

8 minute read

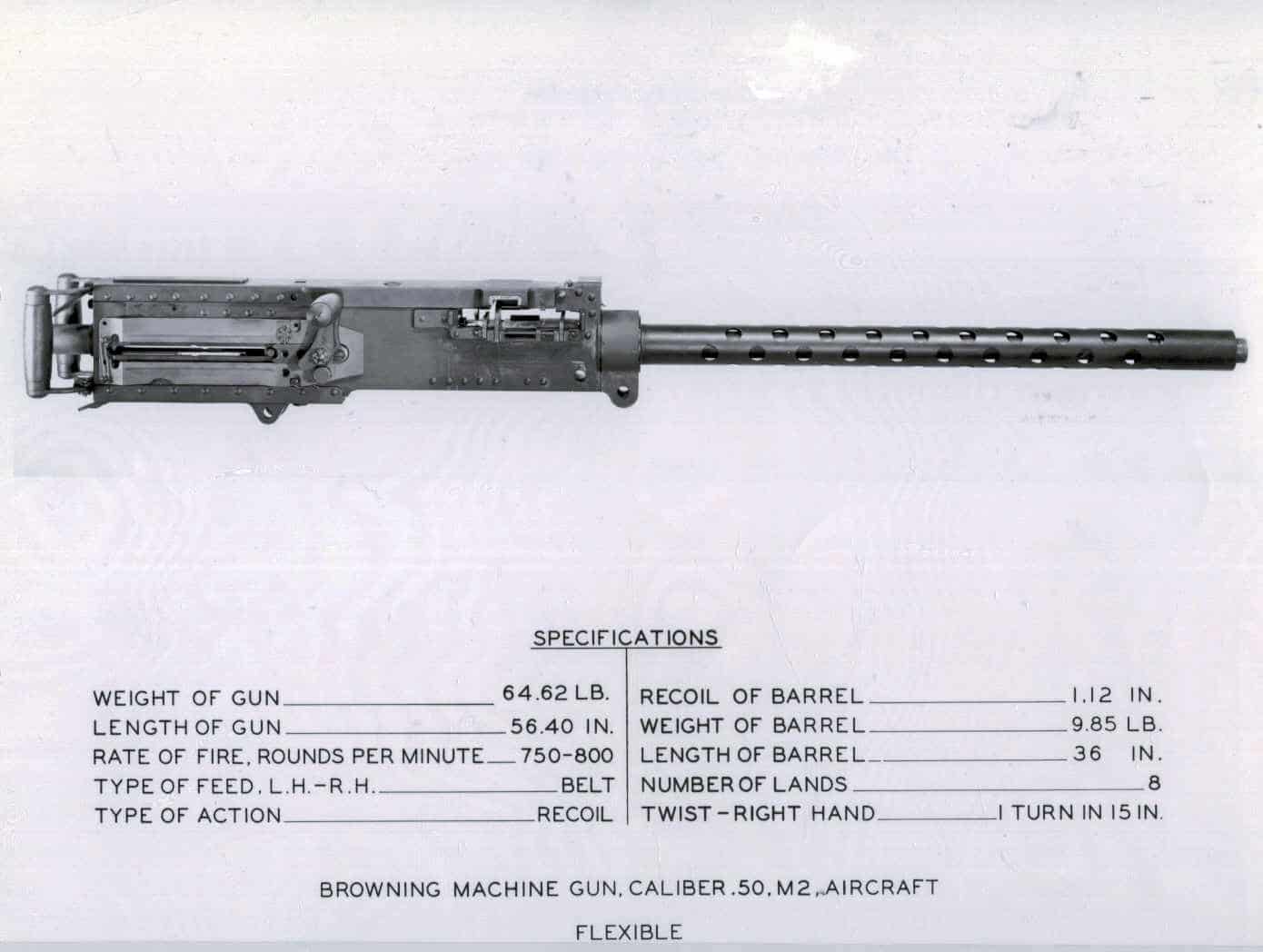

As the world once again marched towards global war in the late 1930s, U.S. Ordnance had developed the Browning .50 caliber machine gun into an effective aircraft weapon. In a rare instance that found the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy in agreement, the Browning .50 caliber AN/M2 was adopted for service in American military aircraft. The “AN” prefix stood for “Army-Navy”, and the light barrel version of the M2 (61 lbs.) ultimately became the standard weapon for almost every significant American combat aircraft of World War II.

The AN/M2 was available in two versions: Fixed guns were mounted in the wings, power turrets or in the nose (synchronized with the propeller) and were fired by an electrical solenoid. Flexible guns, mounted in the rear cockpit of dive bombers and torpedo planes, or in fuselage positions of medium and heavy bombers, were manually aimed and fired by the gunner. Later in the war, remote-control gun turrets were featured on a few aircraft, including the B-29 Superfortress, the A-26 Invader light bomber and the P-61 Black Widow night fighter.

Training the Air Gunners

During World War I, America trained its prospective air gunners (both pilots and observers in two-seat planes) in the basics, but using some rather advanced training tools. One of these tools was a “camera-gun” that was close in size and shape to a Lewis machine gun. The photos taken when it was “fired” allowed instructors to see if the gunner trainee was at least close to his target in the mock air-to-air combat.

Other gunnery training methods included firing MGs from a tripod at silhouette paper targets pulled on a track on the range. All in all, America’s aerial gunnery training was particularly advanced by World War I standards. After the war however, budgets were slashed, and most air gunner training was abandoned.

America’s concepts of “strategic bombing” were born during World War I, but few people had even heard of the notion even into the late 1930s. Shortly before the Pearl Harbor attacks, the new Boeing B-17D “Flying Fortress” featured seven machine guns for defense (six .50-caliber guns, and one .30-caliber gun in the nose). The next Flying Fortress, the B-17E, featured a total of 10 .50 caliber guns, including a powered top turret, a tail turret and two waist guns. The final version of the aircraft, the B-17G, carried thirteen .50 caliber guns. As the USAAF strategy of daylight strategic bombing progressed, American heavy bombers were expected to fight their way unescorted through to the target, deep inside enemy territory, and then fight their way home again. The need for effective aerial gunners grew beyond anyone’s expectations.

The U.S. Army Air Forces developed its first school for air gunners in June 1941 at a small installation in Las Vegas, Nevada. During World War II, the air gunner training program expanded to massive proportions, and additional schools were established at Kingman and Yuma in Arizona, Harlingen and Laredo in Texas, and Panama City and Fort Myers in Florida. In the combat theaters of operation, most bomb groups also had their own schools for more intensive training on the specific weapons and mounts used in those squadrons.

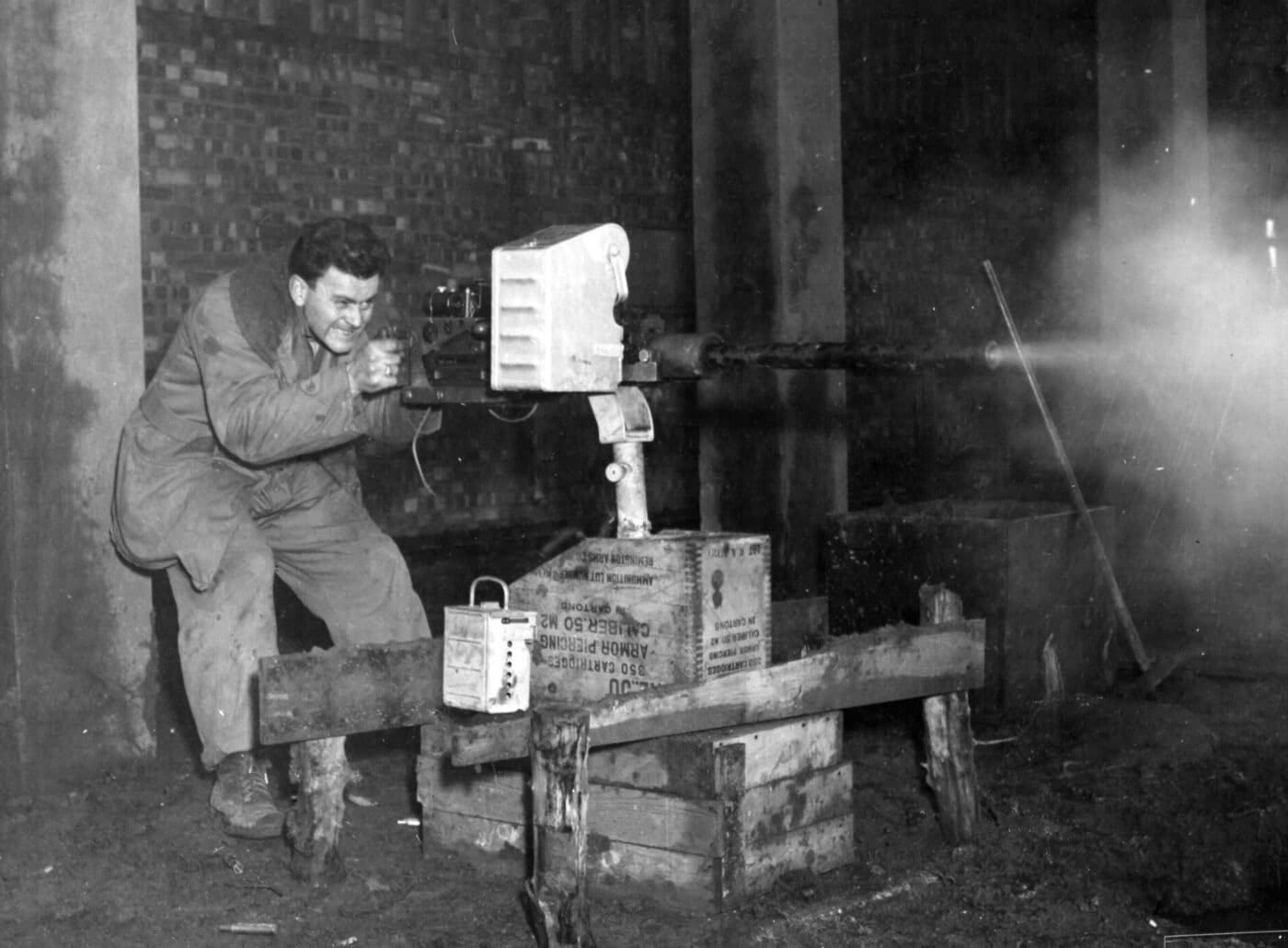

Stateside training for air gunners consisted of an intensive six-week course. While the training program was the most comprehensive of any combatant nation, this was an ongoing struggle between proponents of “theoretical training” (classroom sessions) in air gunnery and the great need for practical instruction in the operation and use of the Browning .50 caliber AN/M2 machine guns.

Gunners were split between those assigned to power turret positions and those that aimed and fired their weapons by hand (the “flexible” guns). Turret gunners were faced with the mechanical nuances of multiple turret types created by several manufacturers. Different bomber types used different turrets, and it was impossible to train the gunners on every turret they could potentially use in combat. Proper maintenance of the turret guns was also the gunners’ responsibility, and the men had to know how to fix the firing solenoids as well as how to clear jams while in combat.

The complexities of the systems began to overwhelm the time and resources of the training programs. Combat squadrons complained that too many new gunners could not maintain their .50-caliber weapons — some unable to handle “head-spacing” for their Browning machine guns.

Gunfights in the Clouds

In the high-altitude air battles over Europe, the heavily-armed B-17’s and B-24’s proved their ability to defend themselves against Luftwaffe interceptors and still effectively strike targets deep within the Third Reich — but only at great cost. The US 8th Air Force suffered more than 47,000 casualties, including more than 26,000 dead. The 15th Air Force suffered more than 20,000 casualties among their bomber crews. German flak and fighters exacted a heavy toll.

But even in the earliest missions, when there were no fighters capable of escorting the “Big Friends” to their targets, the bomber formations were never prevented from reaching their targets. Despite the heavy casualties, German industry was hammered, and many Luftwaffe interceptors paid the ultimate price when they closed in on American bomber formations. Even though there were few occasions when the bomber gunners could get in a long, accurate burst, the hell-storm of .50-caliber fire peppered with plenty of tracer rounds proved greatly intimidating to enemy interceptors. Few pilots enjoyed the prospect of taking a .50-caliber round into their windscreen.

Initially, Luftwaffe interceptors made their attacks from the rear. The twin .50 caliber tail gun positions of U.S. heavy and medium bombers quickly made this a highly dangerous method of interception. The massed firepower of multiple “Tail End Charlie” in the bomber boxes forced most Luftwaffe interceptors to break off their attacks before they could close to within 500 yards of the bombers.

The Germans quickly changed tactics to head-on attacks — as this meant they faced the least amount of defensive fire from the bombers’ guns. The USAAF responded with updated designs of the B-17 and B-24 that featured nose turrets with twin guns to meet the threat. Head-on attacks continued, but the more than 600 mile per hour closing speeds meant that both the interceptor and bomber gunner had little time for a well-aimed burst.

Eventually, the Germans developed specific bomber assault squadrons with heavy armament (20mm and 30mm cannons) as well as increased armor protection for the pilot and the engine. The heavy weapons packages and extra armor for German single-seat fighters were useful in some ways, but the added weight shortened range and endurance, reduced speed and generally made the aircraft easy meat for U.S. escort fighters that were later introduced.

Ultimately, daylight bomber interception was an ugly, bloody, aerial gang fight. If the Germans wanted to hack down the Flying Fortresses, they had to get in close to do it. The closer they got, the more the .50-caliber MGs tore them apart. In a strange twist, some of the most advanced technology of the war returned the combat to its most primitive form, while the battles raged at 20,000 feet.

WW2 Gunners: Overlooked Heroes?

The air gunners played the same deadly game as fighter pilots, and their successes were recorded in the same fashion. Even so, the 305 enlisted air gunners credited with five or more aerial victories are rarely remembered as “aces”. Aerial victories in the world wars have been notoriously difficult to confirm, and attributing kills to specific gunners, often when multiple guns from several aircraft were firing at the same target are even more suspect.

Even so, their official record stands, and a massive number of Axis interceptors fell in flames in the face of their .50-caliber firepower. The highest scoring USAAF gunners were all sergeants: Michael Arooth, a B-17 tail gunner with the 527th Bomb Squadron (8th Air Force) was credited with 17 victories; Arthur Benko (a B-24 top turret gunner) of the 374th Bomb Squadron of the 14th Air Force (China-Burma-India) was credited with 16 kills; and Donald Crossley, a B-17 tail gunner with the 95 Bomb Group (8th Air Force) shot down 12. The air gunners had done their jobs, they protected the bombers, and the Axis nations lay in ruins beneath them.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

475

475