An Eternal Warrior — The M14

July 13th, 2020

8 minute read

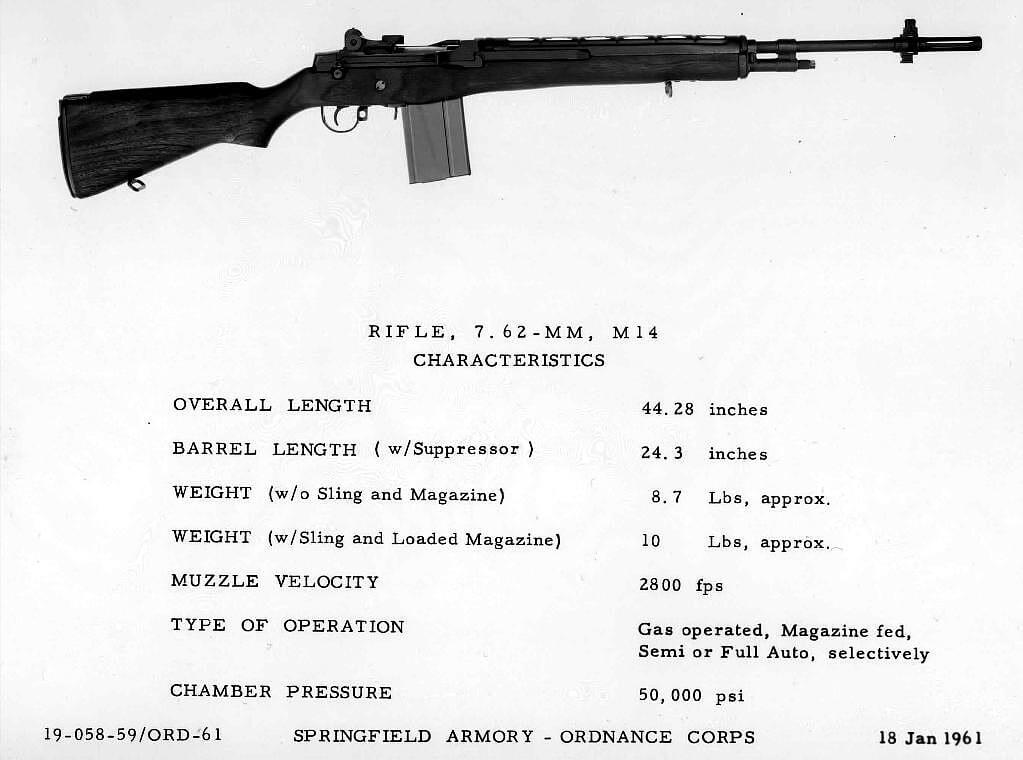

While everyone today tends to think of the M16 when it comes to U.S. military rifles, there is another rifle with an even longer history. That rifle is the M14, and it has remained in service longer than any other U.S. military rifle, from 1958 until the present day. At the same time, the M14 served as the U.S. Army’s standard infantry rifle for the second-shortest period, from 1958 until 1968.

This strange historical dichotomy confuses some firearms enthusiasts and leads to some rather lively debates about the M14 and its qualities as a battle rifle. Along those same lines, the purpose of this article is to discuss the reasons why the M14 was created in the first place, and to provide more historical context around its development and use.

Son of the M1

When John Garand began the design process for the semi-automatic M1 rifle, the U.S. military already had a great battle rifle: the M1903 Springfield, chambered in .30-06. The M1903 is arguably the finest bolt-action rifle ever fielded. Coupled with the M1917 rifle (often called the “American Enfield”), the M1903 had been one of the key weapons of the Allied victory in World War I. Few military experts suspected that U.S. Ordnance would seek to find an improvement over the beloved Springfield rifle.

Even so, John Garand began to work (to learn more about that process, click here) on America’s new semi-automatic rifle in 1922, and after much engineering, refinement and revision, the M1 rifle was standardized in January 1936. By the end of World War II, nearly 5½ million M1 rifles had been produced while John Garand’s namesake won battle honors everywhere the weapon served. General George Patton called it “the greatest battle implement ever devised”.

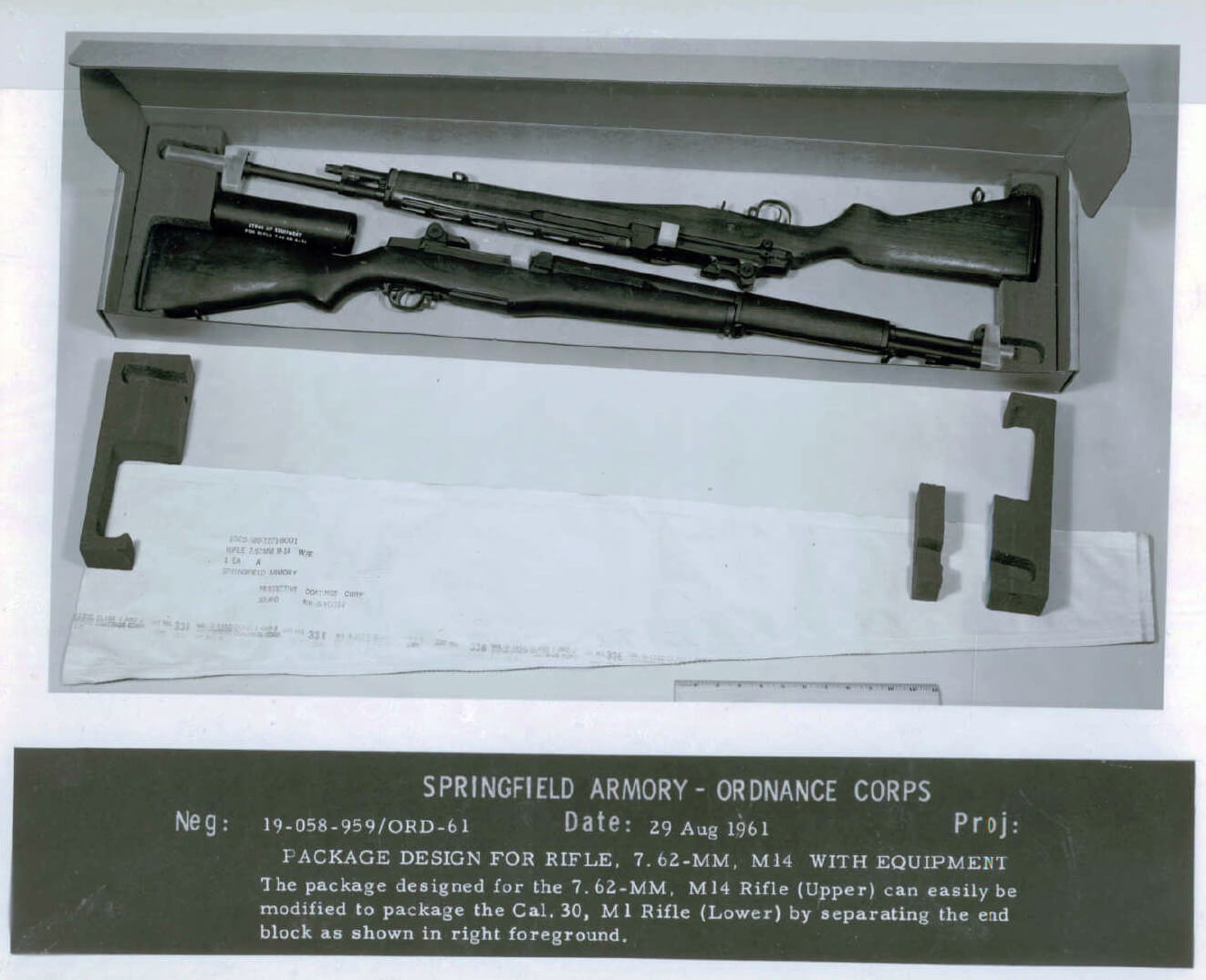

Again, most military experts did not predict that U.S. Ordnance would seek to improve on a combat-proven veteran. And once again, those experts were mistaken. By 1946, serious efforts to upgrade the M1 rifle were already underway. Practical considerations played their part too, and when the 7.62mm M14 rifle was finally selected, the new rifle could be produced on M1 Garand equipment that was already in place. Also, several internal parts were interchangeable between the M14 and the M1.

A New Fuel

The U.S. military fought World War II with many small arms chambered for the high-powered .30-06 round. However, during the war, combat ranges were noted to have dropped dramatically, with most normal infantry engagements taking place at 300 meters or less. The Germans noted this and developed their “Sturmgewehr” series of selective-fire rifles to use their new intermediate 7.92x33mm (7.92 Kurz) cartridge. This, in turn, dramatically influenced the Soviets, who developed their own M43 cartridge (7.62x39mm), which would ultimately drive the development of the AK-47.

The new American round — the 7.62mm T65 — harnessed practically the same power as the .30-06, but in a shorter cartridge. A new gunpowder formulation created by the Olin Chemical Corporation allowed U.S. Ordnance to retain most of the ballistic characteristics of the .30-06 cartridge in a shorter and lighter round. This cartridge would later be modified to become the standard 7.62×51 NATO round (adopted by the United States in 1954).

The select-fire M14 was designed to use the new NATO round, as was the new M60 machine gun (which was expected to condense U.S. shoulder weapons and machine guns to just two types).

Born in USA

During the extensive competition between the M14 and the Belgian-designed FN FAL (the M14 as “T44E4” versus the FN rifle as the “T48”), one aspect of that tight race was quite clear: the M14 was homegrown and the FN was not. Both are excellent rifles, and both used the new 7.62×51 NATO cartridge. Their capabilities showed mostly as being neck and neck, with the deciding factor quite often being the shooter’s preference. The Belgians even offered their rifle with no licensing cost.

As fine a rifle as the FN FAL was for its time, it was not an American design. That simple fact made it unacceptable to most U.S. military leaders, the architects of the Arsenal of Democracy. Even so, the competition between the two rifles was fair (to learn more about the competition between these two designs, click here), but ultimately the U.S. military chose the all-American product.

The Everything Rifle

America emerged from World War II with a large inventory of small arms types: the M1911 pistol (.45 ACP), the M1 Carbine in .30 Carbine (to learn more about the M1 Carbine, click here), the M3A1 submachine gun in .45 ACP (to learn more about the submachine guns of World War II, click here), the M1 Garand rifle in .30-06, and the Browning M1917 (water-cooled) and Browning M1919 (air-cooled) machine guns in .30-06. Ordnance logistics had become complicated and cumbersome.

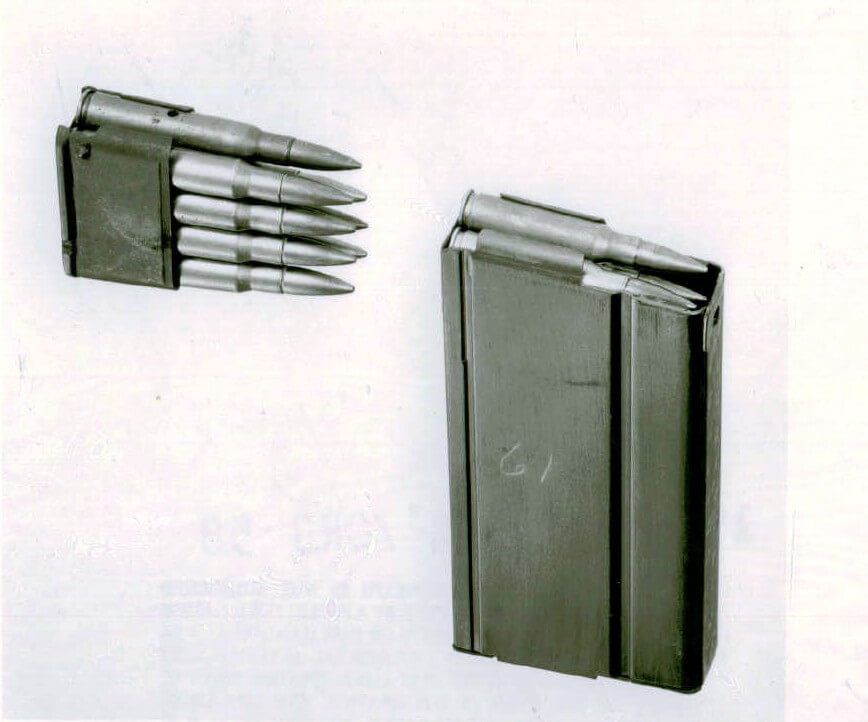

The M14 introduced a new cartridge and a new concept to America’s arsenal. The 7.62x51mm NATO cartridge was considered “intermediate,” and at the time of its introduction, it was. As the M14 was produced as a selective-fire weapon, available in several barrel-length and stock configurations, it was considered flexible enough to replace several other weapons in the U.S. inventory. That idea did not work out.

Since the end of World War I, designers have sought to balance a battle rifle’s weight, plus that of its ammunition, the rifle’s accuracy and range, and its level of firepower (from bolt-action to semi-auto to selective fire). It is a difficult equation, and any ten infantrymen around the world will provide you with at least a dozen opinions on the subject. The M14 was developed and tested, accepted and fielded, at the beginning of a highly contentious era of small arms design.

Studies of World War II combat casualties among infantrymen were reviewed and a few powerful conclusions were drawn: most infantry combat happened at close range and those units with the most firepower were normally the winner. Also, it came to be believed that the number of enemy casualties was directly related to the amount of rounds fired at him. U.S. troops would be expected to carry more ammunition into combat, and fire more of it, more quickly, than ever before. For right or for wrong, these calculations would have significant impact on U.S. small arms design during the 1950s. In some ways they would affirm the decision to go with the M14, and in other ways they would contradict it.

In the end the M14 proved to be too much gun to replace America’s submachine gun, and not quite enough to take over the squad automatic role (to learn more about the M14 as a squad automatic, click here). Thankfully, the massive global conflict that the M14 was built for never materialized.

Unexpected Conflicts

The abilities of the American rifleman are not myths or legends, they are facts. Americans are great riflemen, and that is our heritage. The M14 rifle built on that world war-winning legacy. Its development was based on the U.S. Army’s expectations of its needs in the next war — and that was expected to be another massive conventional conflict, probably fought in Europe.

Many comparisons have been made between the M14 and the Soviet AK-47 (to learn more about this, click here). Both rifles were developed at approximately the same time, but the Soviets chose to create a simple rifle that better suited the needs of the Red Army. While U.S. Ordnance was not impressed with captured examples of the German Sturmgewehr during World War II, the Soviets were very impressed with the German rifle, particularly the 7.92mm “Kurz” cartridge it used. The Soviets in turn, developed their own M43 7.62x39mm cartridge that followed a similar pattern as well as the SKS and AK-47 rifles to use it.

Even though closer in style to the M14, the SKS carbine made little impression on U.S. Ordnance during its brief career as the Red Army’s primary battle rifle (to learn more about the SKS, click here). As for the AK-47, U.S. Ordnance documents describe it as a “submachine gun” until the early 1960s. However, as the amount of “brushfire” and guerrilla wars around the world increased dramatically, the AK-47 was quickly perceived as the perfect weapon for insurgent forces. The image of the AK-47 would quickly become an icon of communism and rebel forces around the world.

On the other hand, the M14 would give way to the M16 during 1968, and that rifle would become an icon of the American military in the later Cold War-era. However, the M14 would continue to soldier on in specialized roles in the U.S. military through to today. And, while it may have been the shortest serving standard infantry rifle in America’s history, its continued service in numerous other roles has proven its merit.

On the Other Side

And, thanks to the efforts of today’s Springfield Armory, you can own your own civilian-legal semi-automatic version of the M14 in the M1A. Offered in variants from Standard Issue versions to compact SOCOM 16 versions to National Match and Super Match models to more, the new M1A is a great option for fans of the M14.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

366

366