Anzio Annie — The German Krupp K5 Railway Gun

October 15th, 2024

11 minute read

Heavy artillery has been a been a battlefield-dominating weapon since World War I. Even today, the big guns continue to do their deadly work in the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Across the many conflicts of the past century, a handful of giant artillery pieces have earned a special reputation ahead of all others. One of these is the Krupp K5 280mm railway gun from World War II.

During the Battle of Anzio, January 22 to June 4, 1944, two of these massive guns earned the nicknames “Anzio Annie” and “Anzio Express” from the beleaguered Allied troops at the hemmed-in beachhead.

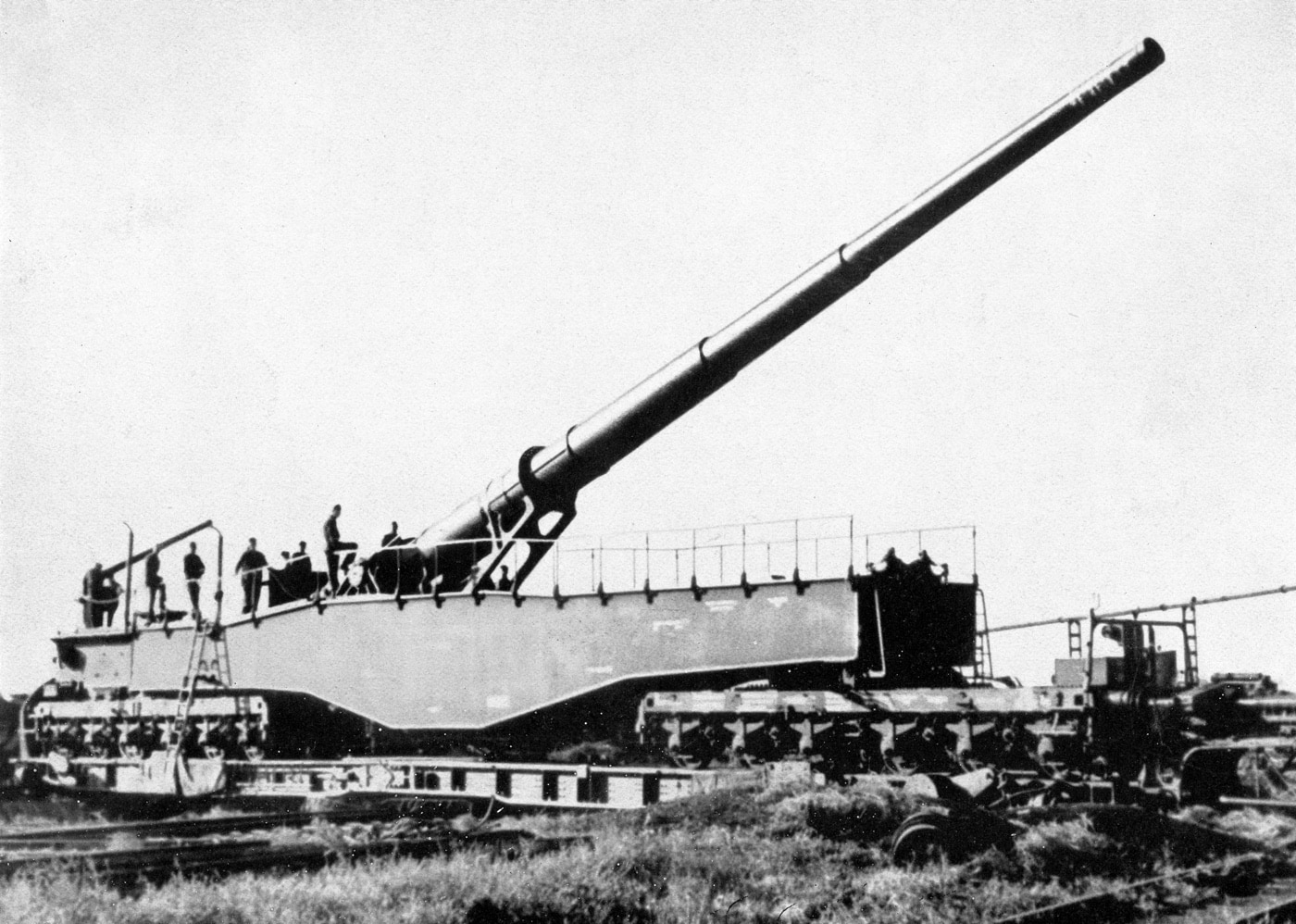

Krupp K5 — A Railway Giant

Development of the Krupp K5 gun began in 1934, and after successful testing there were eight of the railway guns available for the German invasion of Belgium and France in May 1940.

There were some early problems with the 83-foot-long barrels (283mm or 11.1 inch caliber), with fractures occurring due to problems with the rifling, featuring twelve 10mm grooves. This fault was quickly identified and resolved by using shallower (7mm) grooves, and the K5 guns remained in service throughout the war.

The Germans had hoped to use the K5 guns to interdict enemy shipping in the English Channel, but the guns proved unable to track precise, moving targets at a great distance. To improve the railway guns’ flexibility in acquiring targets, the “Vogele Turntable” was created.

This allowed the K5 to fire from a raised rail, with 360 degree traverse on circular track. This allowed the weapon to be a formidable siege gun — proven out when the K5s were used at Leningrad, Stalingrad and Sevastopol during the war in Russia.

The following description comes from a March 1945 U.S. Ordnance review of German artillery:

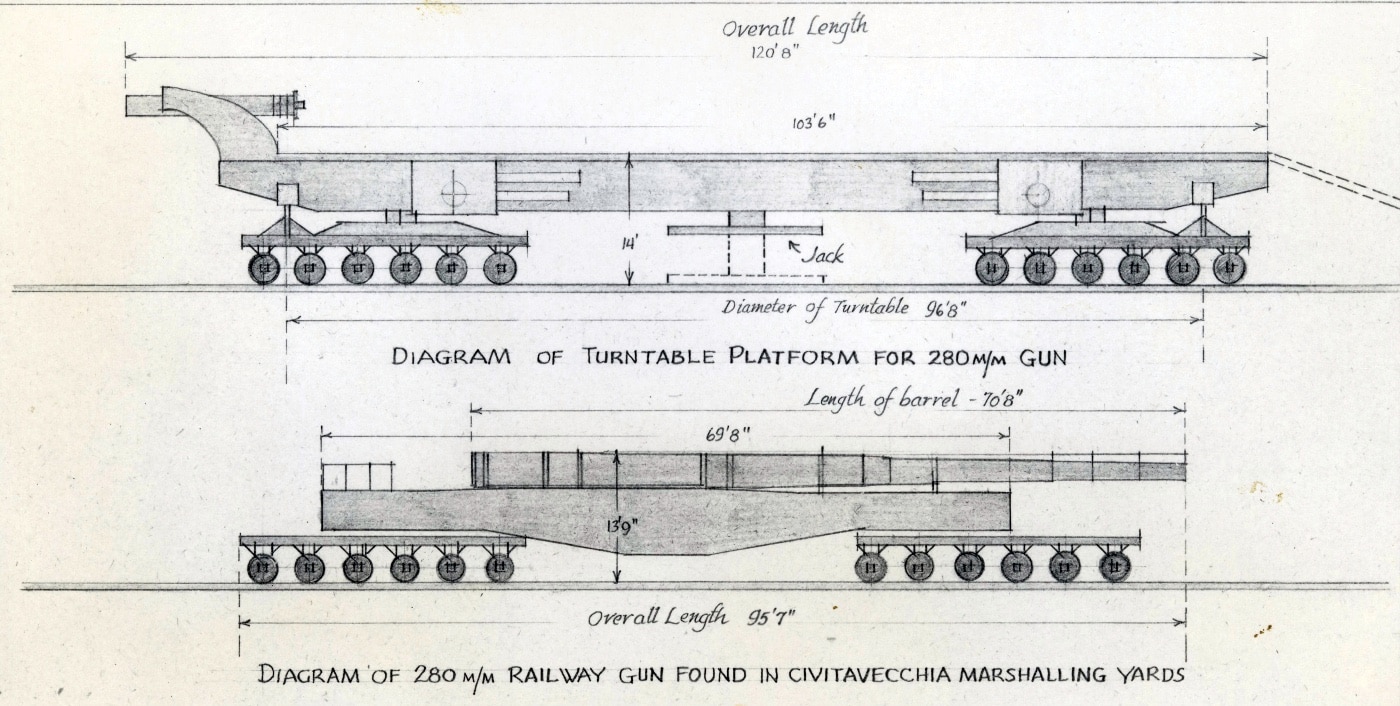

The German 28 cm K5 (E) has an unconfirmed range of 31 miles and fires a pre-engraved projectile weighing approximately 550 pounds. It is fired from a turntable affording a 360° traverse.

The gun has a 70-foot 8-inch barrel held in a sleeve-type cradle. The barrel recoil mechanism, fitted between two arms projecting downward from the cradle, consists of two hydro-pneumatic cylinders and a single hydraulic buffer cylinder. The cradle is supported by trunnions which rest in bearings on top of a box-like frame, of girder construction, which in turn is supported on two pintles resting in bearings in the center of two 12-wheel trucks. The front pintle bearing rides in a rail on the front truck and can be positioned six inches either side of center, thereby allowing a car traverse of approximately 1 degree.

The equipment in effect has a double recoil action. Besides the barrel recoil which is approximately 32 inches, the gun car recoils. It is coupled to the front of the turntable platform by a hydraulic buffer and a hydro-pneumatic counter-recoil mechanism which returns the car to battery position.

A turntable platform is transported as part of the equipment and in transport forms a flat car with a 103-foot bed resting on two 8-wheel trucks. A central jack helps support the tremendous weight of the gun and carriage which amounts to around 230 tons and also serves as a central pivot for the turntable.

The powder chamber is approximately 10 feet 5 inches long. Obturation is obtained by means of a short brass cartridge case and the breech is closed with a horizontal sliding type of breech-block. Firing is of the percussion type.

Weight of the projectile is approximately 550 pounds.

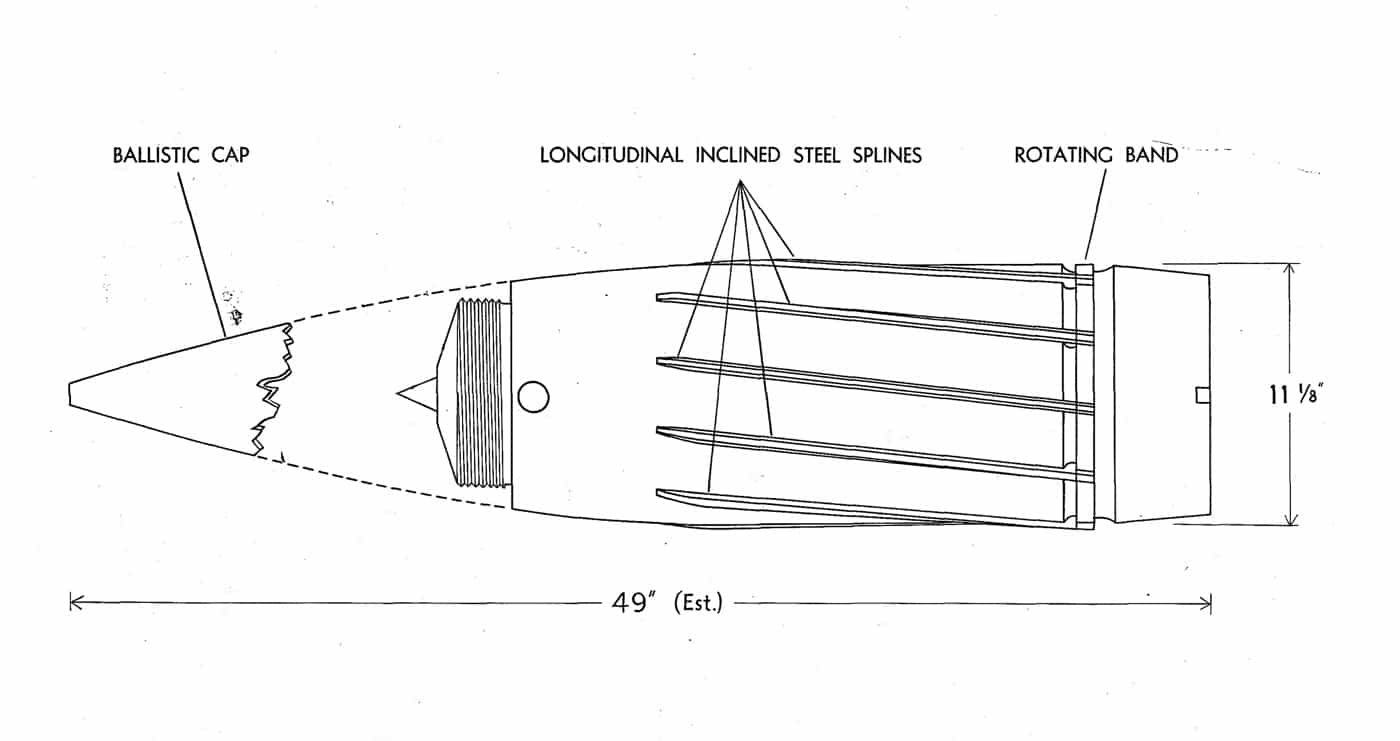

An additional Ordnance report describes the K5’s unique 280mm ammunition:

The pre-engraved, projectile recovered in Italy is used for long range bombardment. It has longitudinal inclined steel splines and a single one-inch-wide copper band that acts as a gas seal. The splines are set at a slight angle to the axis of the projectile and are 19.2 inches in length. In loading the projectile, the splines are lined up with the rfling of the gun tube. The shell is 33 inches in length, exclusive of the windshield. Fragments indicate that the windshield would add an extra two feet to the length.

A nose percussion fuze (AZ 35 K) and a base fuze (BD Z 35K) are fitted. The Germans are reputed to have four types of 28 cm railway guns able to employ this type of projectile. They are: 28 cm Br. N. Kan E.; 28 cm K. 5 (E); 28 cm K. 5/1 (E); and 28 cm K. 5/2 (E).

German Railroad Guns Gain Infamy in Italy

The Anzio landings caught the Germans by surprise. Unfortunately for the troops of the invasion force, their leaders were content to move inland slowly and secure their beachhead. This gave the Germans valuable time to assemble their forces to contain the invasion.

Heavy artillery was an important part of this force. The Germans deployed 15 cm, 17 cm and 21 cm guns, and about two weeks after the landings, the two 28 cm K5 guns of “Eisenbahnbatterie 712”, arrived to contribute their fire to reduce the Anzio-Nettuno beachhead.

Taking full advantage of their observation positions in hills surrounding the area, German artillery began to strike the vulnerable supply depots bunched up on the beach.

A German report from February 8, 1944, stated: Our artillery laid harassing fire on important enemy supply routes, and engaged enemy artillery with counter battery fire with observed results. The harbor of Nettuno and the airport east of it were shelled by 17 cm cannons and railway guns.

The official history of the U.S. 5th Army details the impact of the German shelling, and specifically mentions the fire of the two railroad guns:

On the afternoon of February 5 the air strip at Nettuno was heavily shelled. Five Spitfires were destroyed, and the field had to be abandoned as a permanent base. Thereafter planes used the field only during the day, returning each night to bases near Naples. On February 7, a heavy-caliber railroad gun was reported near Campoleone on the railroad which passes through Cisterna and Campoleone on the way to Rome. Reconnaissance planes discovered additional heavy guns and railroad guns on the slopes of Colli Laziali: 170-mm guns were located on the edge of a cliff near Lake Nemi, and a railroad gun was spotted near the mouth of a tunnel at Albano. Although the shelling from these long-range weapons was seldom accurate, the rear areas of the beachhead were so congested that material damage and casualties were inevitable. The most serious effect was in delaying the work of unloading supplies in the port.

The effect of the massive 28 cm shells went far beyond the material damage they caused. Their effect on the morale of the soldiers stuck in the Anzio pocket was significant. When German bombers appeared overhead, the Junkers and Dorniers could be fired at, and some were brought down. But there was no defense against the 550-pound projectiles as they crashed in with the sound of a runaway freight train. The randomness of the huge blasts meant that no one, officer or private, combat infantryman or supply worker, was safe at Anzio.

An article in “Stars and Stripes” described the G.I.s’ fears of the K5’s bombardment:

The beachhead troops learned to recognize their gruesome, thundering scream. They told how one shell split through three floors of a thick, stone building beside the harbor. They told how another crashed through an ancient Roman cave in Nettuno and how a third uprooted men from their foxholes. A fourth ploughed into the Anzio cemetery unburying the dead.

Consequently, the 5th Army’s efforts to locate and destroy the railroad guns were far out of proportion with the damage the K5’s caused. The 5th Army history notes:

To hamper enemy observation of the right side of the beachhead XII Air Support Command sent P-40’s and A-36’s to attack the water tower at Littoria on February 7. The next day railroad guns west of Albano were bombed. Hits on the track and a burst of yellow flame and smoke from the target area indicated that the guns had at least been damaged.

The second mission of enemy artillery was constant harassing of the vulnerable beach and port areas and of the trunk roads leading out of Anzio. For this the enemy employed 170-mm rifles with a range of 32,000 yards, 210-mm railway guns, and even 280-mm railway guns known to our troops as the Anzio Express. The amount of enemy shelling during March indicated that the Germans were not withholding ammunition for an assault but were taking advantage of their superior positions to inflict as heavy casualties as possible.

The Germans were prepared for Allied aerial reconnaissance, and in addition to hiding the K5 guns in a various railroad tunnels, they also created dummy guns complete with muzzle flash and gun smoke decoys to fool snooping aircraft and Allied artillery spotters. The dummy guns used telephone poles for barrels and their camouflage was purposefully never quite good enough.

Nicknames, both German and American

When the K5 guns began firing on American positions, the G.I.s quickly knew they were targeted by artillery they had never faced before. As the 550-pound shells hurtled into their target, the fearsome sound reminded the troops in their foxholes and bunkers of an express train passing overhead. The regular arrival of the K5 shells gave rise to the first G.I. nickname: the Anzio Express. As the battle wore on and the guns continued to bombard the beach, the troops began to call the gun “Anzio Annie”.

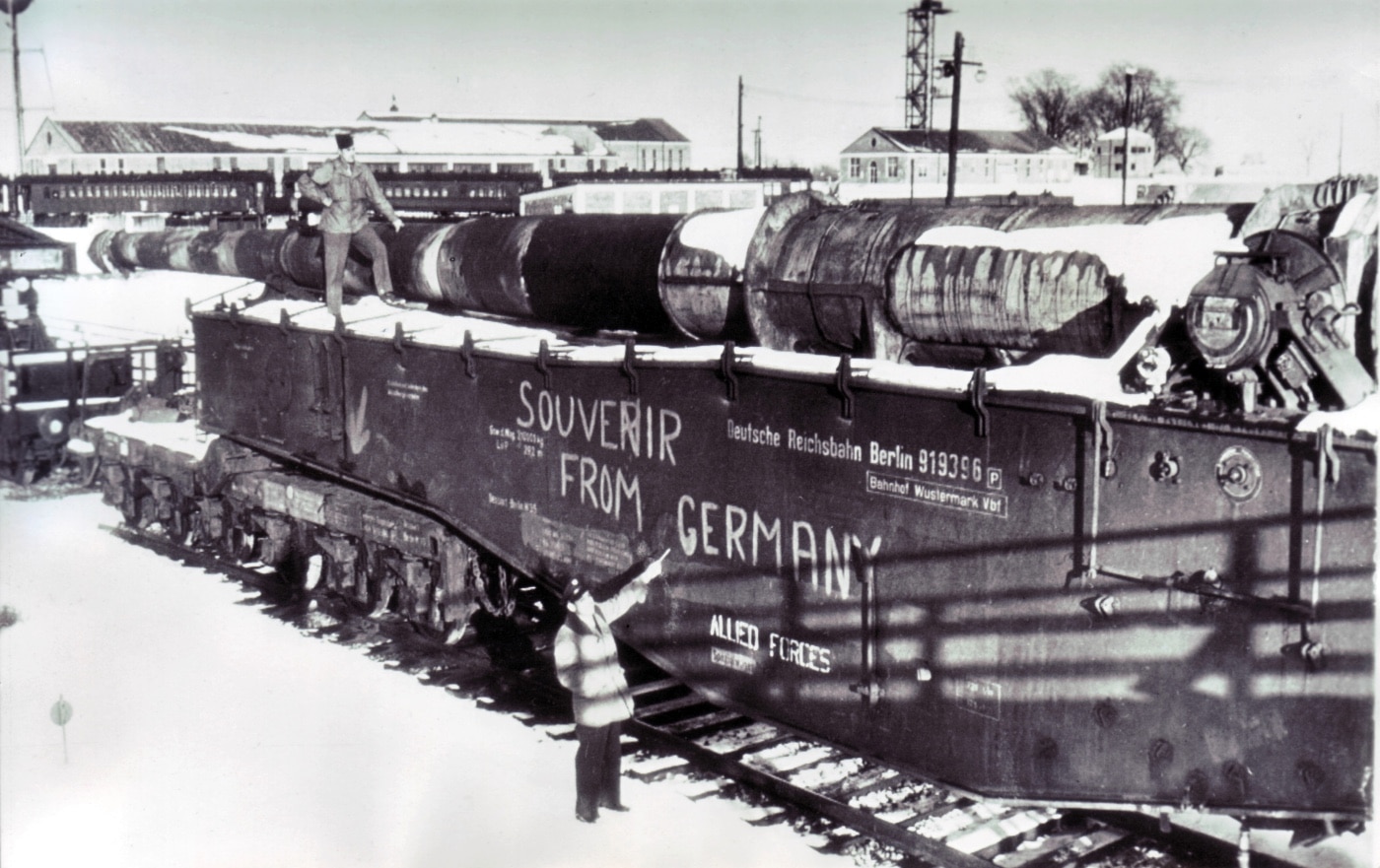

On the German side of the lines, the gun crews of Railway Gun Battery 712 had named their twin guns “Robert” and “Leopold”. It remains unknown when the Allied forces at Anzio realized they were being fired upon by a pair of Krupp K5 guns.

Thundering Giants Hiding in Tunnels

While the Allies search frantically to find the K5 guns, the Germans had them hidden in, of all places, a railroad yard at Ciampino. Their firing position had them easily pointed at the Anzio beachhead, allowing them to target most of the Allied position without constructing the Vogele Turntable as a dead give-away.

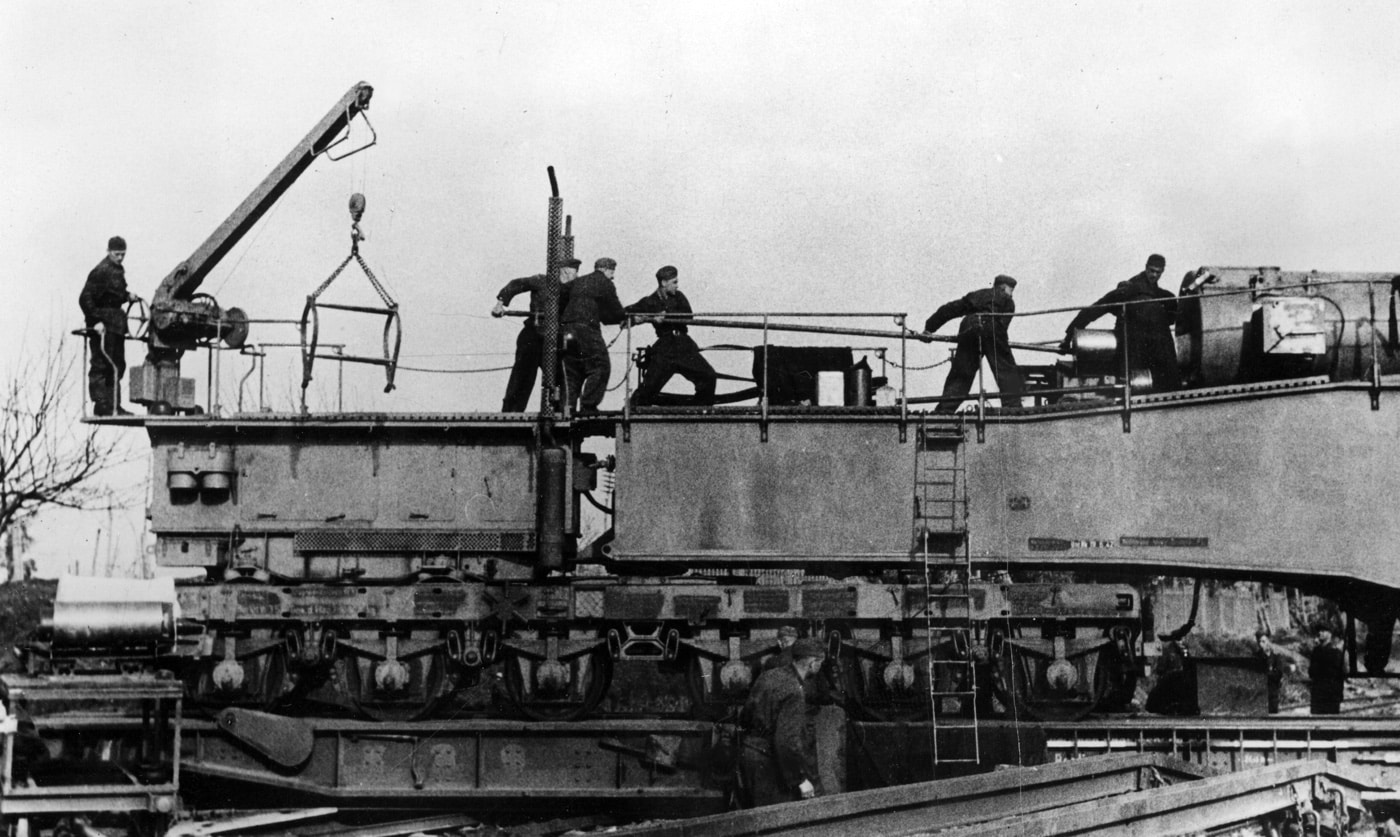

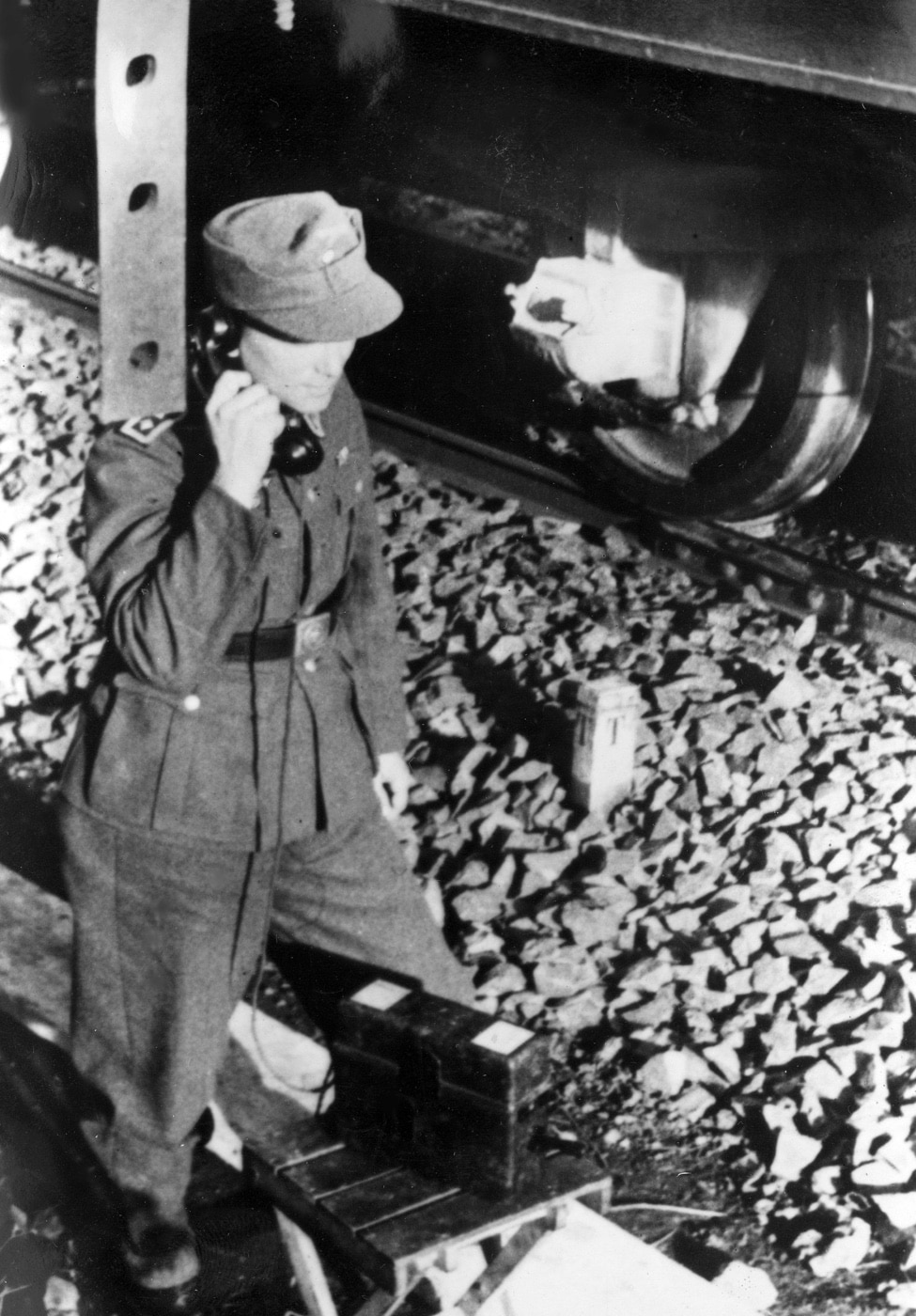

At the far end of the yard was a conveniently located railway tunnel, that served as the K5 guns’ hideout. Leopold and Robert could emerge into their firing position, fire several rounds while receiving correction from their forward artillery observers, and then return to the safety of the tunnel.

The Ciampino yard was beyond the range of any Allied counter-battery fire, and there were multiple other heavy artillery batteries active in the German zone. This, coupled with the railroad gun decoys, kept the Allies from discovering the K5s’ location for quite some time.

Before they began firing, the big guns received as much preparation as possible while they were still within the safety of the tunnel. Once they emerged from cover, the first round would be a special “ranging shell” that allowed the spotters to quickly adjust their fire onto the target. The ranging round hadn’t even hit yet while the K5 barrel was lowered, the spent casing extracted, and the new round inserted. By the time the first shell struck and the spotters were reporting the needed corrections, the railroad gun could be quickly adjusted to the target and fired again.

The normal firing sequence of the K5 took seven minutes — the techniques of the crews at Anzio reduced it to four. In 30 minutes, they could get off up to eight rounds and then vanish into the tunnel. It took between four to seven minutes to reload and fire the gun. This meant in a half-hour or so they could fire six to eight rounds — usually enough to find and devastate the target — and then the gun would disappear back into the safety of the tunnel. To help mask the firing, the Germans would add a bag of Deuneberger salts to their powder mix to reduce the muzzle flash.

By early March 1944, the guns had managed to fire more than 300 rounds into the Allied beachhead. On March 8th, they hit a fuel depot and the resulting fire sent flames up to 1,000 feet in the air. Leopold and Robert, or Annie and the Express, had not been found or silenced.

Quietly though, the German gunners had a significant problem: throughout the course of the battle the two guns would fire more than 500 rounds, so much that it exhausted Germany’s supply of available 28 cm ammunition. Meanwhile, even though the railway guns were not bombed directly, the limited amount of railway lines leading to the area were under constant attack. Ammunition was not only running out, what little was left couldn’t get through.

On April 6th, the Allies recovered a 28 cm dud, and this provided them with much more information on the K5’s capabilities. Even so, the guns were not located until May 28th. The next morning, P-40 fighter-bombers attacked the tunnel mouth and, although neither gun was damaged, the gunners knew their time was up. That evening, Annie and the Express fired off their remaining 16 rounds, and escaped in the darkness.

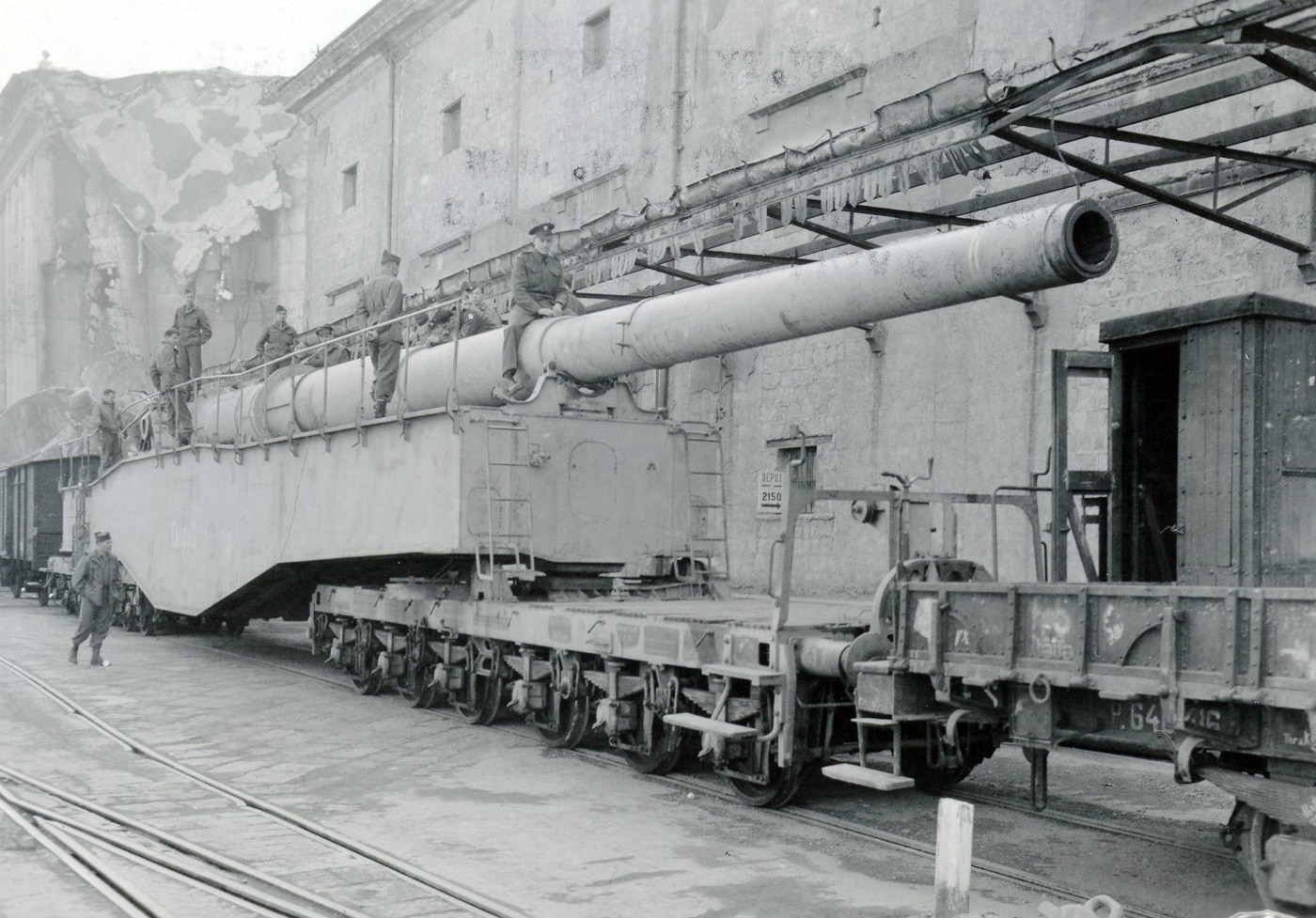

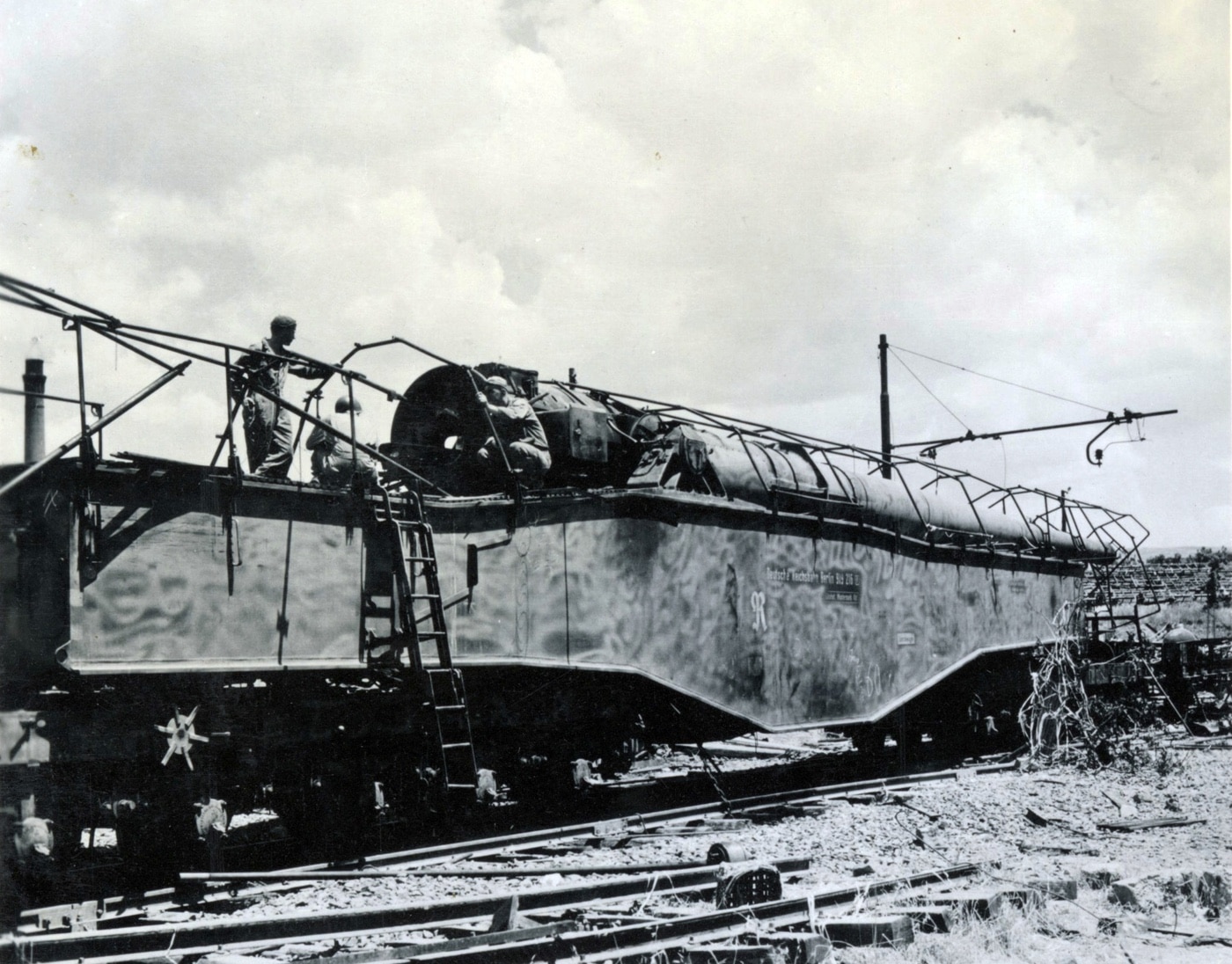

Any useful rail lines to the north were wrecked, so the guns were diverted to the port of Civitavecchia in hopes of evacuating them by ship. But it was too late, and the Allies were advancing too fast. When no sea-going transport arrived, the crews did their best to disable the guns before the Allies could capture them.

Both guns were captured by American troops, and Leopold was sent to the United States to be tested at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland. Leopold was on display at the U.S. Army Ordnance Museum at Aberdeen until 2011, when it was moved to Fort Lee in Virginia, where it is in long-term storage at the U.S. Army Ordnance Training Support Facility (not open to the public).

Parting Shots from the K5 Guns

The Krupp railway guns fought in several actions in France during 1944, notably bombarding the British invasion beaches in Normandy, firing on Allied troops in Rouen and dueling with American heavy artillery in Lorraine. During the Battle of the Bulge, the K5 guns threw nearly 400 rounds at American positions. When the bitter end came in May 1945, Germany’s great railroad guns came to the end of the line without hope or even ammunition.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

76

76