Ayoob: Can Shooting a Revolver Make You Better with Your Semi-Auto?

May 28th, 2022

8 minute read

We are in a time when the semi-automatic pistol predominates in the handgun world. After all, in the 2/4/22 edition of The Shooting Wire, industry insider Jim Shepherd reported that only one out of 10 handguns sold today is a revolver. When some shooters are asked about revolvers, they’ll reply, “Wheelguns? In the 2020s? What are you, a cave person?”

In my 50th year as a firearms instructor, I’ve spent decades telling students that a double-action revolver will help teach them how to shoot their autoloader better. And it’s still as true as the first time I said it. Here’s why.

Combat Semantics

There are many words for the way we bring the trigger straight back toward us as we break a shot we hope will strike exactly where we aimed it. Even non-gun people use the term pull the trigger. “Hey, boss, let’s pull the trigger on the new business project!”

Of course, a “pull” can also describe a mighty “yank,” and we all know that would be deleterious to accuracy. So, by at least the 19th century, marksmen advised those they taught to shoot to squeeze the trigger.

However, “squeeze” implies an encircling inward pressure that is not present when we activate a trigger for an intended shot. Realizing this, in the mid-20th century, Lt. Col. Jeff Cooper became perhaps the first shooting authority to advocate that we press the trigger.

Cooper was an extremely articulate man who knew his semantics, but there were semanticists who quibbled with even his word. To most people, they argued, “press” connoted an outward pressure, like pressing the button on an elevator or a car radio. Since we were bringing the trigger back toward ourselves, the semanticists argued, shouldn’t “pull” the trigger be the correct term after all?

If the simple act of discharging a firearm can evoke this much “combat semantics,” we know that we’re talking about something that may be more complicated than it sounds, at least if we hope to get good results.

Revolver Training: Distribution Factor

I think we’d all agree that what we want is an evenly distributed rearward pressure that doesn’t pull the muzzle off target before the shot breaks. The long, relatively heavy pull of a double-action revolver (or double-action autopistol) is hard to master, but it forces the shooter to distribute that trigger pressure.

Back in the day when the double-action revolver dominated, the debate was between one-stage and two-stage pulls. One stage meant a single sustained rearward pressure until the shot broke. Two-stage was essentially “trigger-cocking”: the shooter would bring the trigger back until the bolt locked the cylinder on some revolvers, or until he or she could feel the “stacking” of a V-mainspring of others as the two sides of the spring closed into contact at the bottom. Then, they would ease the trigger the rest of the way as with a cocked single-action. Some revolver shooters installed little rubber trigger stops that looked like tiny pencil erasers to achieve a two-stage feel.

The two-stage pull has pretty much gone the way of the Dodo bird with serious double-action revolver shooters. It was easy to overshoot the first stage and break the shot before the sights were where the shooter wanted them, and keeping that from happening slowed down the shot.

Even at long range, double-action was found to be superior to single. If a clock was running, it took time to thumb the hammer back and then re-grip, and breaking the hold to do so interfered with the consistency of grasp. On most double-action revolvers, the hammer fall was shorter in double-action than from the single-action cocking notch. This made lock time — the interval between the beginning of hammer fall and the discharge — shorter, leaving less time for human error to allow the sights to stray from where they were when the shooter finished the trigger stroke.

But the main thing was that the long double-action pull allowed more of a surprise break, which in turn prevent a trigger jerk when the shooter decided, “Shoot NOW!”

The shorthand explanation: The double-action forces you to distribute trigger pressure. Which is a cure for jerking the trigger. Which improves shooting performance.

So, here’s the deal. We know we have to keep the handgun (or any firearm, really) indexed on the target as we bring that trigger to the rear to send the shot on its way. With a handgun, unless you are holding something absolutely huge and heavy with its hammer cocked, you are exerting a poundage of pressure that is greater than the weight of the firearm itself, directly upon said firearm. If you don’t bring the trigger straight back — if you don’t divert the muzzle the slightest bit off the target — the bullet will fly true to your chosen point of aim.

The trick is in distributing that trigger pressure to prevent the jerk, the mash, the “got it NOW!” convulsion or whatever your particular coach chooses to call it, that pulls the muzzle off target as the firing pin or striker is coming forward in the irrevocable moment of truth that is The Shot.

That rearward pressure must be even. It must be consistent.

And a revolver, fired double-action for every single shot, can help us learn to master that distribution of trigger pressure. In fact, for many shooters, it will help us learn that better than anything else.

The Transfer

The skill learned in manipulating a double-action revolver trigger transfers easily to the shorter trigger stroke of the semi-automatic pistol. It is essentially a revolver pull, in microcosm, over a shorter length of travel.

There is another advantage of the “revolver pull applied to the auto” — you’ll never again “short-stroke” — that is, fail to reset — your auto’s trigger.

The double-action revolver shooter quickly learns to allow the trigger to return all the way forward between shots. If he doesn’t, the trigger will either lock up, or rotate the cylinder without raising or lowering the hammer.

A semi-auto shooter following the popular mantra of “don’t let the trigger return all the way forward, but just enough to feel the tick of the sear resetting” can find his gun not going bang when he wants it to, because the trigger has not come forward enough. The more pressure the shooter is under, the more likely this is to happen. Under stress, particularly in a fight or flight state, physical strength increases greatly and suddenly, but dexterity and fine motor skills go just as swiftly down the toilet.

If you’ve ever seen a frightened person turn deathly pale, you’ve seen vasoconstriction in action. Vasoconstriction is part of fight or flight response: the body redirects blood flow away from the extremities. It’s as if the fingers “go to sleep.” We very likely won’t be able to feel that tiny “tick” of the trigger resetting. But if we let the trigger come all the way forward, that’s still gross motor enough for even a vasoconstricted finger to feel that the autoloader is ready for the next shot.

In the early days of target shooting with cocked revolvers and single-action autos with light triggers, shooters learned to press the trigger with the pad of the index finger. Double-action revolver shooters for the most part used “the power crease,” the distal joint of that finger on the palmar surface, to get more leverage for heavier pulls. The “service auto” trigger pulls of most striker-fired guns and a “street” as opposed to “match” 1911 can benefit from this greater leverage, too.

If a student has been jerking his or her trigger, I’ll often have them stand on the sidelines with their gun hand’s index finger upraised, so they can watch it and the revolver shooter I’ve told them to observe. As the wheelgunner fires each shot, I tell the student, keep your finger going at the same pace. Their trigger finger keeping pace with the wheelgunner’s helps them develop trigger pressure distribution.

Watch Out For …

The autopistol shooter accustomed to a straight thumbs grasp, particularly with the support hand well forward, needs to watch out for a couple of things with revolvers. A thumb in contact with the rotating cylinder can cause a revolver’s barrel to deviate from point of aim. The thumb can also come far enough forward to be in the way of gas and debris spit from the barrel/cylinder gap.

Also, with a heavy (up to 14 or so lbs.) double-action trigger pull, a hard hold on the gun is essential to keeping it on target. That transfers in a positive way to the auto shooter as well. Curling thumbs down, popular with revolver shooters, maximizes grip strength and helps stabilize the gun.

Bottom Line

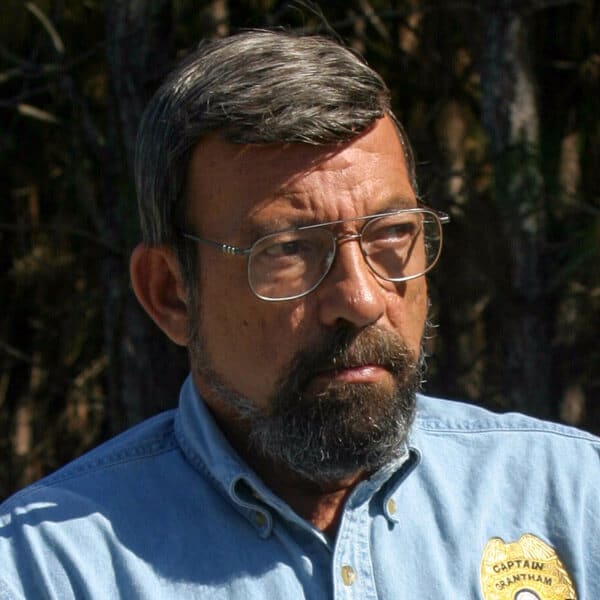

Do you feel that your shooting with your autopistol needs improvement? Spend a month shooting your double-action revolver. Expense doesn’t need to be great. A .22 rimfire such as the old High Standard Sentinel in my photos illustrating this article will do. We’re not working on recoil control, remember, but trigger control.

Give it a try. You’ll very likely find, as many of us long-time instructors have found, that double-action trigger time with a revolver will make you a better shot with your semi-automatic pistol.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

90

90