Battle of Iwo Jima — Returning to the Black Sands

February 19th, 2024

13 minute read

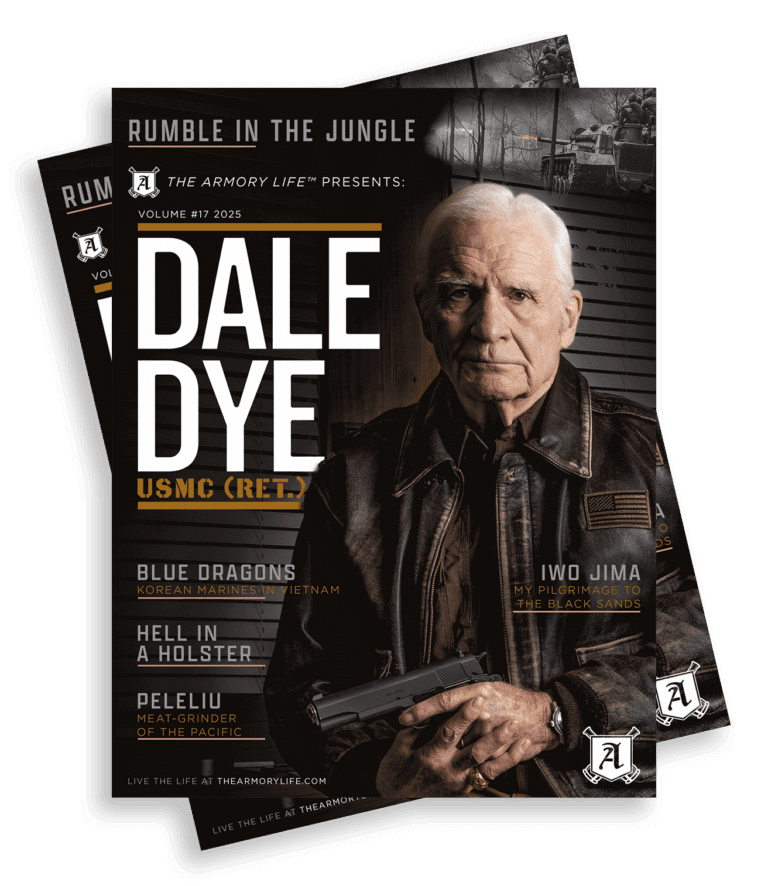

On 19 February 1945 — 79 years ago today — the US Marine Corps began the bloody work of taking Iwo Jima from the Imperial Japanese Army. Casualties were extremely heavy — nearly 7,000 Americans killed and close to triple that number wounded. In today’s article, Capt. Dale A. Dye, U.S.M.C. (ret.) describes his experiences in visiting that historic volcanic island.

Unless you’re a Marine, it’s likely you don’t know that the Corps has its own version of the Haj, the annual pilgrimage that all Muslims are expected to make once during their lifetime. Devout Muslims make the trek to Mecca. Devout Marines — if they’re lucky enough — make a soul-stirring journey to Iwo Jima.

It’s a rare opportunity for most Marines, but I’ve been blessed to make that Haj three times, walking the infamous black sands and standing on the very spot where five men back in 1945 raised the American flag atop Mount Suribachi and created an image so timeless and impactful that it has come to visually define the Marine Corps.

Setting My Path to Iwo Jima

My first visit to what is now called Iwo To by the Japanese government was really an accident. I was flying across the Pacific aboard a KC-130 that developed engine trouble and had to land on the sulfur island as a precaution. Say what you will about that Marine aircrew regarding flight safety and NATOPS procedures, but I’ll always believe they ginned up that detour just so they could say they’d been on Iwo Jima.

Back in those days of the mid-1960’s, there wasn’t much more than a small Japanese Self-Defense Force garrison and a detachment of US Coast Guard technicians running a Long Range Aid to Navigation (LORAN) station on Iwo Jima. They seemed more interested in whacking golf balls into black sand traps than exploring the island’s pivotal place in World War II history. Not much to see in those days other than a few rusty relics and a chance to climb Mount Suribachi.

But looking down from that perch over the volcanic beaches was still awe-inspiring for a Marine steeped in the lore of the Corps. For years, I longed to return, so I armed myself with maps and began a knee-deep study of the battle, hoping for a future opportunity. I went into research mode and learned a hell of a lot more than I was taught in boot camp history classes.

[Check out Tom Laemlein’s article on WW2 American flamethrowers.]

Contested Ground

On maps of the vast Western Pacific, Iwo Jima is a flyspeck located about 750 miles southeast of Tokyo, Japan. It’s part of the Volcano Islands south of the more familiar Marianas Islands (Guam, Saipan and Tinian) for geographic reference. And it turns out, early explorers — for reasons not explained — named the island after a grinding bowl used in Japanese cooking.

Mount Suribachi is the highest point on the island at 554 feet above sea level. Otherwise, the eight square miles of Iwo Jima are relatively flat, featureless and composed mainly of dark volcanic sand. There are two other similar but smaller islands in the Volcano Group, but they were never contested during World War II. Iwo Jima proper — and later Okinawa — were the primary targets of the Allied powers slogging toward the Japanese homeland in early 1945.

As usual in Allied strategy during the island-hopping campaigns of war in the Pacific, the focus was on airfields. Iwo Jima had three of them (designated Motoyama 1, 2 and 3), making the island an ideal fighter escort base as well as a refuge for bombers damaged during raids on the Japanese mainland.

America’s new B-29 Super Fortress long-range, heavy-duty bombers had been striking Japanese home island targets since the summer of 1944, and these raids required escort by fighter aircraft that didn’t have the legs to reach Japan from more distant bases. Iwo was also an ideal location for damaged Super Forts to conduct controlled crashes or land for repairs before returning to airbases in the Marianas. Allied planners realized all this. So did the Japanese.

There was also a certain last-ditch, face-saving element involved for the Imperial Japanese Forces reeling from defeat elsewhere in the Pacific. Iwo Jima was considered a part of Tokyo Prefecture. If Iwo fell, it would be the first part of the traditional homeland to be captured by their enemies. Iwo Jima had to be heavily defended, so they sent a couple of their best to fortify the island and command its defenders.

Lieutenant General Tadamishi Kuribayashi would command the soldiers and Rear Admiral Toshinosuke Ichimaru, a naval aviator, commanded naval forces. Kuribayashi had better than two regiments of infantry, plus artillery and heavy mortar outfits, and a tank battalion on the island. Ichimaru controlled two large fighter units, a construction battalion and a bunch of coastal defense and AA units. It all amounted to around 20,000 Japanese defenders on the island.

They went to work with tenacious defense as a single-minded purpose. All over Iwo’s eight square miles of volcanic ash, Japanese forces found, cleared and reinforced natural caves. They dug in like termites all over Mt. Suribachi at the island’s southern tip where the high ground dominated both of the island’s possible landing beaches.

Every inch of those beaches was zeroed in for enfilading fire. Blockhouses and pillboxes flanked the landing areas. Machine guns were sighted for deadly interlocking fire. Rockets, anti-boat and anti-tank guns were emplaced with wide-open fields of fire. When the calendar flipped to 1945, the Japanese were ready.

A Marine’s Second Look

With all this in mind and a set of copious notes, I visited the island for a second time as Marine Combat Correspondent based in Hawaii. It was coming up on the 45th anniversary of the Iwo Jima fight when I conned my way into a solo visit to the island by promising a feature story based on something nebulous like “the ghosts of Iwo Jima.” Call it hubris, but I thought I might somehow channel both defenders and attackers if I could spend a week or so crawling that old, remote and relatively unchanged battlefield.

The first thing I noticed was the smell. There’s an obvious and odious miasma that hangs over Iwo Jima. It’s no wonder Marines and others called it sulfur island. The place reeks of that element and reminds constantly that you’re walking around on a dormant volcano. Seeking escape from the heat and odors, I climbed Mount Suribachi and stood on the spot where a patrol from the 28th Marines of the 5th Marine Division raised the American flag.

There’s a monument up there marking that spot where AP correspondent Joe Rosenthal took his immortal still photo of the flag-raisers. Those included Pima Indian Ira Hayes, immortalized much later by a popular Johnny Cash song that could have been the original anthem for PTSD.

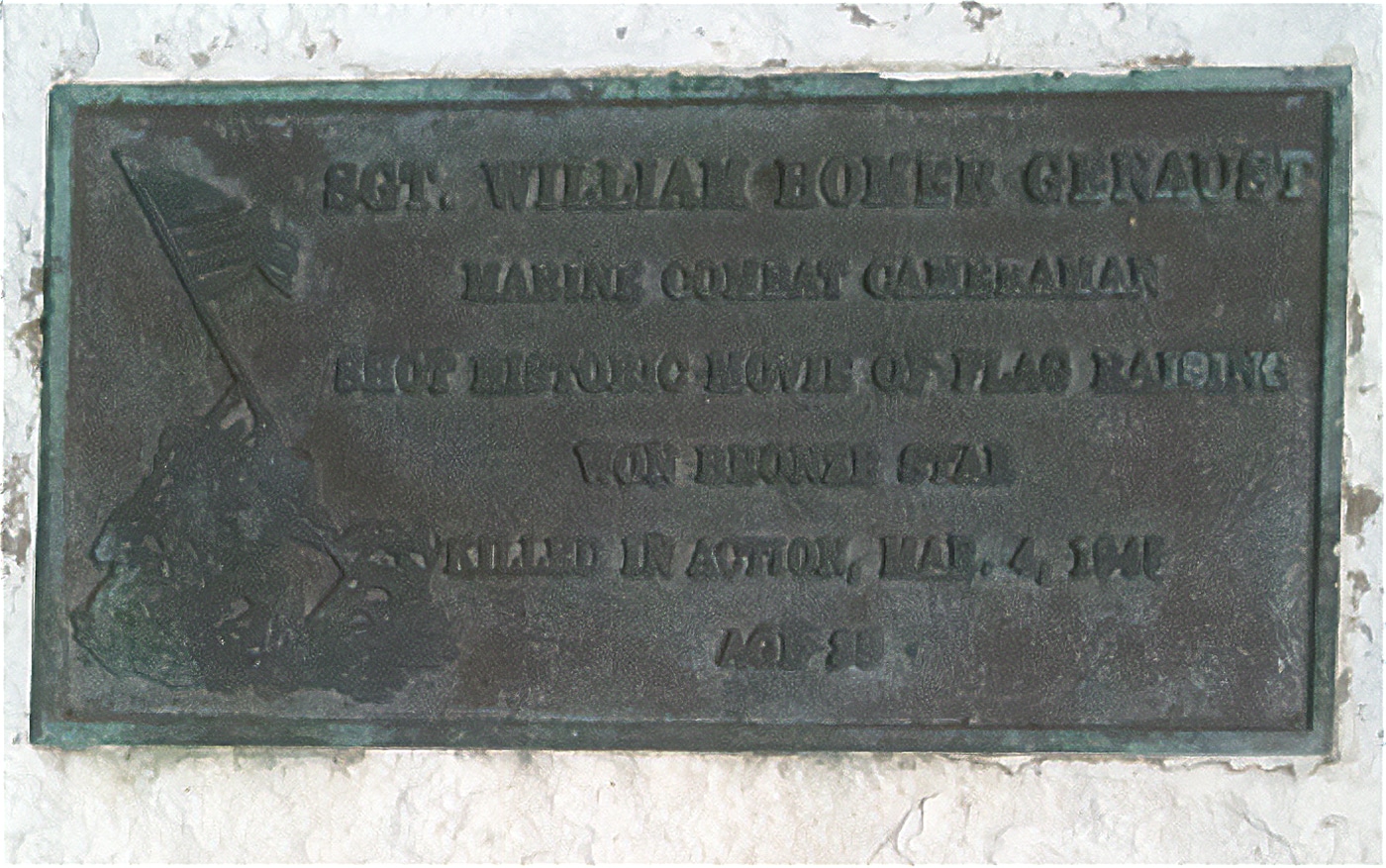

And I thought about a lesser-known photographer who also captured that drama. Marine Sergeant Bill Genaust shot 16mm color film of the flag-raising. His brief view was eventually shown as a patriotic trailer in theaters all across the nation and later became a standard in early TV signoffs. Genaust was killed on Iwo and his body never recovered.

Picking up a white basalt rock from the flag-raising summit, I stepped down a bit onto a ledge that overlooked the landing beaches and sat thinking about the V (Fifth) Amphibious Corps (Marine Major General Harry Schmidt) and the units that bobbed around in LVTs on the morning of 19 February 1945.

Below me, stretching from southwest to northeast were beaches Green and Red (5th Marine Division/Major General Keller Rockey), Yellow and Blue (4th Marine Division/Major General Clifton Cates) over which some 70,000 US Marines — including the 3rd Marine Division (Major General Graves Erskine) in Corps reserve — would eventually land on this porkchop-shaped island.

Iwo Jima had been blasted and pummeled from air and sea for weeks prior, which tore away at Japanese positions above ground but hardly touched the maze of underground fortifications. That left the assaulting Marines with just one tactic — frontal assault.

At Great Cost…

D-Day was nothing short of a bitch-kitty for those men as they struggled for traction over the shifting, slippery black sand of the landing beaches. One step up and three steps back just to reach the beach plateau.

Fighting their way through constant enemy fire and high-explosive raining down on their helmeted heads, plus mass confusion on overcrowded beaches, littered with burning and wrecked landing craft, the assault elements lost nearly 600 killed and some 1,800 wounded that morning while barely getting a toehold on Iwo.

One of those who died on a black sand beach was Gunnery Sergeant John Basilone who had been awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions on Guadalcanal. He didn’t have to be there on Iwo, but Manila John wanted to be where he could use his experience to help others survive.

February 19 was just the first of 36 bloody days it took to secure Iwo Jima. Below my perch on Suribachi were other infamous battle sites such as the Quarry, the Amphitheater, Turkey Knob, Hills 362A, B and C, and the Motoyama airstrips. As much as possible, those were the sites I wanted to explore.

A Lonely Pilgrimage

America had returned Iwo Jima to the Japanese in 1968, but the government in Tokyo didn’t show much interest in the restored island at first. Quasi-official visitors like me were pretty much left on their own to explore. And a military history nerd like me knew where to do that. I crawled through numerous caves that still contained rusty weapons, ammo and little housekeeping items like teacups, canteens, molding equipment and green IJA-issue sake bottles.

Under some rocks in a cave at the base of Hill 362-A, I found two blue and white porcelain mess tins marked with the anchor and rising sun symbol of the Rikusentai, or Japanese Special Naval Landing Force. Apparently, Admiral Ichimaru had some of his own Marines on the island to face their American counterparts.

Practically everywhere in caves and crumbling fortifications, detritus of men at war lay where it had fallen or been discarded more than two decades earlier. Most of it was Japanese origin, including the rusting hulks of heavy-caliber guns like the ubiquitous Type 92 “woodpecker” and it’s lighter Nambu cousins. There were many caves too thoroughly blasted or threatening to collapse, which limited exploration.

Much of the work on Iwo Jima to winkle Japanese defenders out of hiding was done by flamethrowers followed by demolitions or a barrage of heavy-caliber direct fire. But there were enough navigable fortifications above and below ground to give an explorer a nasty close-up look at what fighting must have entailed for attackers and defenders.

A map developed by the Marine Corps after the fighting pointed me to a deep cave complex that was presumed to be General Kuribayashi’s command post. It had been hard hit during the fighting in 1945. Heavy chunks of shrapnel from 16-inch naval shells littered a scorched area around the entrance, but if you were willing to crawl down the tunnels on your belly, you got a close-up look at how the Japanese lived underground.

The cave was full of little nooks, crannies and antechambers, and you always felt like you were headed downward, deeper and deeper into the guts of Iwo Jima. And the deeper you got, the hotter it was. Never mind the shells, bombs and rockets, just breathing in that cave complex was a chore. And in the deepest chamber, a broad rock platform surrounded by shredded wires and remnants of Japanese field phones. Probably where the General received field reports and studied his maps.

At the end of my second visit to Iwo, following a week of spelunking and study of the battle sights at the infantryman’s level, I was in awe of the official butcher’s bill. It was staggering even in comparison to other bloody Pacific battles: 5,931 Marine KIA, 17,272 Marine WIA on the American side of the ledger.

The U.S. Navy lost almost 900 sailors with another 1,900+ wounded. The escort carrier USS Bismarck Sea (CVE-95) sunk after being hit by five bomb and kamikaze attacks. The carriers USS Saratoga (CV-3) and USS Lunga Point (CVE-94) were also damaged by kamikaze attacks. In total, 18 U.S. ships and gunboats were damaged or sunk during the invasion.

Japanese defenders lost nearly everyone involved in the battle. Barely a thousand of 20,000 original defenders survived. Most committed suicide or eventually crawled out to surrender after a few weeks of starvation. And some of them held out by raiding Allied positions at night for water and provisions. The last two surviving Japanese soldiers on Iwo Jima surrendered on 6 January 1949 four years after the battle ended.

The Final Step

The third and last time I visited Iwo Jima was to attend something called the Reunion of Honor during which American veterans of that battle were transported to the island to meet with families of Japanese soldiers or sailors who died in the fighting. It was a different trip in a lot of ways. No cave-crawling allowed these days, and the Japanese Self Defense Forces have beefed up their presence significantly.

Now civilian access to the island is restricted to things like the Reunion of Honor and other memorial services for the American and Japanese fallen, visits by construction workers and the occasional foray by technicians from various meteorological agencies. And sometimes Marine or Navy Squadrons cruising in the Western Pacific are permitted to use the island’s expanded and improved airstrips for practice carrier landings. Battlefield exploration, souvenir hunting and cave crawling are strictly forbidden.

But I’d gotten in under that wire at least twice and, as I watched a Battalion Landing Team from Okinawa land in modern AAVs (Amphibious Assault Vehicles) across the black sand to honor the surviving vets and complete their own version of the Marine Corps Haj, I couldn’t help but reflect on what I’d discovered on that reeking sulfur island. Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz had it right. “Among those who served on Iwo Jima, uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

681

681