Battle of Peleliu — Revisiting a Meat-Grinder of the Pacific War

September 21st, 2023

17 minute read

September 15 marked the anniversary of the start to the Battle of Peleliu. Spearheaded by the 1st Marine Division, Operation Stalemate II was to take less than a week. Instead, entrenched Japanese defenders utilized the island’s rugged terrain and an intricate system of caves and bunkers to inflict severe casualties on the Americans.

The days stretched into weeks, with U.S. troops suffering from a lack of water while fighting in debilitating heat. U.S. forces suffered more than 10,000 casualties as the amphibious invasion stretched on for more than two months.

The Armory Life contributor and retired Marine Captain Dale A. Dye tells the tale of the battle for Peleliu in a way only he can.

Like most newly minted Marines, I was forced by boot camp curriculum to become an amateur historian. It was part of the drill. You learned about the founding of the Corps and early recruiting efforts at Philadelphia’s Tun Tavern — born in a bar; how cool is that? — and then went on to memorize dates and places significant to the Marine ethos right up to our own time wearing the eagle, globe and anchor. Most of my fellow boots promptly forgot the gritty details when they left Parris Island or San Diego. Not me.

Hooked on the colorful stories of past glories, I kept digging into Marine Corps history like a prospector mining for gold, searching for nuggets that revealed more than dates and generalities. What I thirsted for were insights, first-person accounts from PFCs in the rear ranks. Since there were no living veterans of operations against the Barbary Pirates or the Boxer Rebellion around to interview, my focus fell on infamous battles of World War II in the Pacific. There was still a significant number of old codgers around who had heard the owl and seen the elephant at places like Guadalcanal, Saipan, Okinawa and Iwo Jima.

I hit a vein of pure historical gold one night in a musty, off-base bar when I struck up a conversation with a retired Master Gunnery Sergeant with service as a PFC rifleman with the 1st Marine Division in the Pacific. He served in the 1st Marines under the legendary Col. L.B. “Chesty” Puller, which gave him a certain panache as he revealed some eye-opening details about the deprivations of Guadalcanal in the Solomons and the follow-on fight at Cape Gloucester.

He was salty and sagacious with a sharp memory for detail. Most importantly, he was willing to answer my probing questions from the perspective of a man who had observed those fights mostly through the peep sight of an M1 rifle. We met several times when I could get away from regular duties at Camp Pendleton, and I got a feel for what it must have been like for an 18-year-old from a farming community in Kansas to steam around the Pacific aboard aging, vulnerable amphibs, island-hopping over coral-ringed beaches and crawling through the jungles facing fanatical Japanese defenders.

It was like listening to your grandad or a favorite uncle reminiscing around a campfire, dropping fascinating family gems. Until I mentioned Peleliu. The Master Gunny just shook his head. It took at least three more beers to find out he’d fought with King Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines on Peleliu and wound up barely surviving hotspots like The Point on White Beach 1, the Horseshoe, the Five Sisters and the Umurbrogol massif.

He could only go so far in his descriptions of action on Peleliu and then he just developed a thousand-yard stare across a 20-foot barroom. “Ain’t no way to describe it,” the Master Gunny whispered. “If you wasn’t there on Peleliu, ain’t no way you could understand that rat-bastard of a fight. By D plus four I wasn’t no human being no more. No buddies left. I fired at anything that moved in front of me. I just wanted to kill.”

At that point, I vowed — somehow, someday — I’d find a way to stand on that infamous island and explore Peleliu.

My Peleliu Pilgrimage

It was 50 years later, long after the old Master Gunny had made his last muster when I got my chance. As Military Advisor for the HBO feature “The Pacific,” I was given the welcome assignment to recon some of the island battles we would depict in the TV mini-series to be shot on various Australian locations.

It was a long, complicated flight from LA through Guam in the Marianas to Koror in the Palau Islands. It’s no stretch to say the Palau Islands — particularly Peleliu, where I was headed — is a bit off the standard tourist map. The Palau group is in the Micronesia area of the Western Pacific. It’s an archipelago of some 500 large and small islands. For reference, Guam is 730 miles to the northeast, and the Philippines are 600 miles to the west.

We flew from Guam to the capitol on Koror and got overnight accommodation on the largest island of Babelthuap (Bobble-top) while negotiating for a boat to take us 25 miles southwest to Peleliu where I would spend a week exploring battle sites.

The internet wasn’t as much of a thing in 2010 and even less of a thing on Babelthuap where trans-oceanic phone lines were rare and restricted. I broke out the reference library — mostly Marine Corps historical monographs — that I carried with me and went to work studying the broad brushstrokes of the Palau campaign.

Plans for the Battle for Peleliu

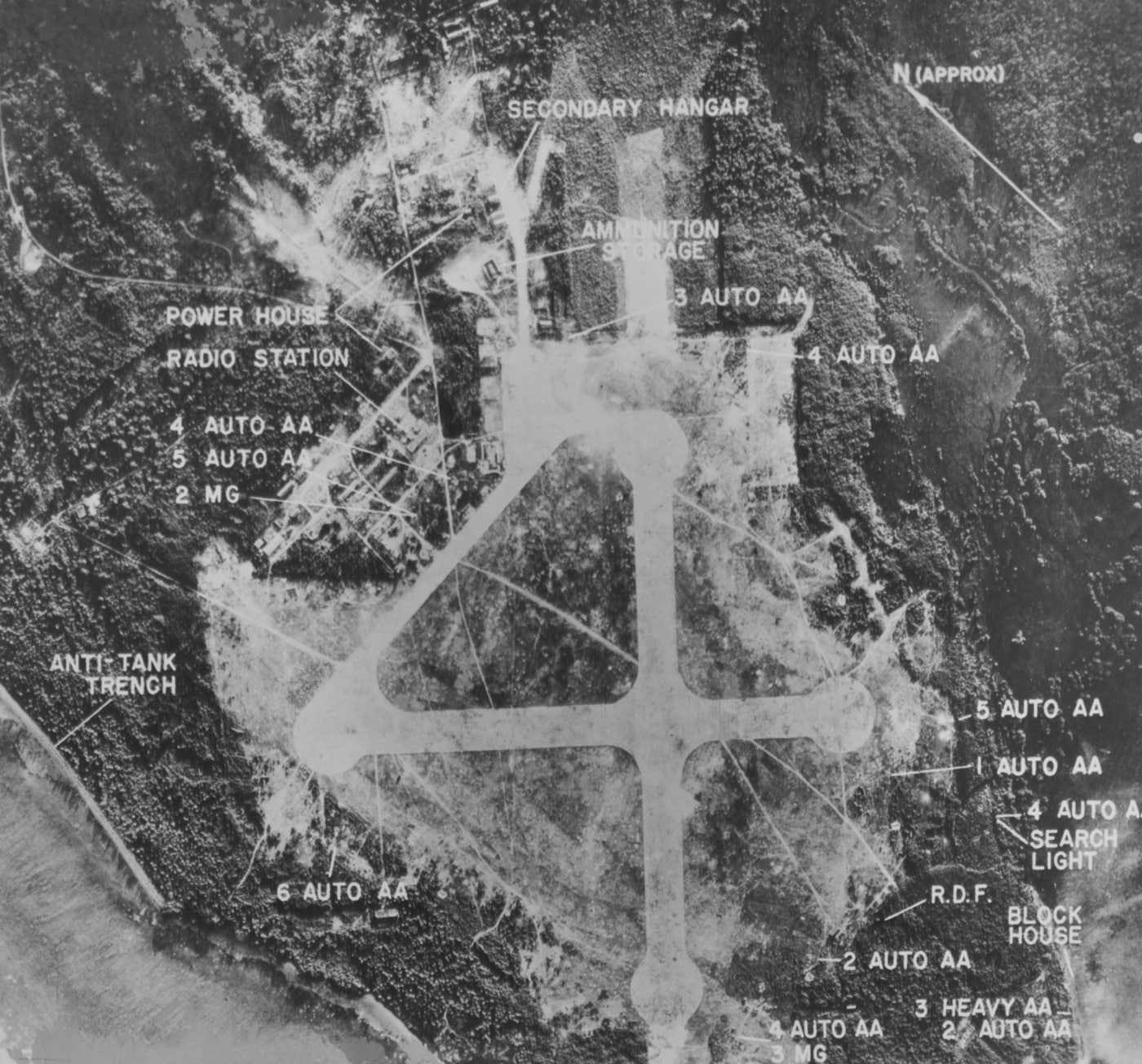

The assault on Peleliu was designed to protect the right flank of MacArthur’s scheduled return to the enemy-occupied Philippines by seizing deep-water ports and airfields that the Japanese might use to disrupt that drive. Palaus had both in abundance, and the Allies were particularly worried about a pair of airfields on Peleliu and Ngesebus (“N’yesbus” in blended Polynesian and Melanesian), a smaller island located just a few hundred meters north.

Admiral Chester Nimitz, with his Navy and Marine staff, cobbled together Operation Stalemate, which would send elements of Marine General Roy Geiger’s III Amphibious Corps to seize major targets in the Palaus with emphasis on Peleliu and Angaur, located seven miles southwest of Peleliu. D-Day on Peleliu was set for 8 September 1944, but flash reports from Admiral Bull Halsey nearly canceled the whole show.

Halsey had been sailing his 3rd Fleet throughout the southern Philippines area, launching repeated air strikes from his carriers. He became convinced that the PI was not as heavily defended as planners anticipated. He recommended that the forces slated for Operation Stalemate would be better employed in the Philippine operations and urged that Stalemate be scrubbed, thus safely isolating the 14,000 Japanese occupying the Palaus on Babelthuap, Koror, Angaur and Peleliu with the majority of Japanese General Murai Kenjiro’s forces dug in heavily on the latter.

Nimitz and staffers dithered, but it was really too late to cancel such a major operation with forces including the Pacific War veteran 1st Marine Division (Peleliu/Ngesebus) and the Army’s untested 81st Infantry Division Wildcats (Angaur/Corps reserve for Peleliu) already afloat in the area. Nimitz decided to proceed with Stalemate II, moving D-Day eight days later than originally planned to 15 September.

Finding Footing

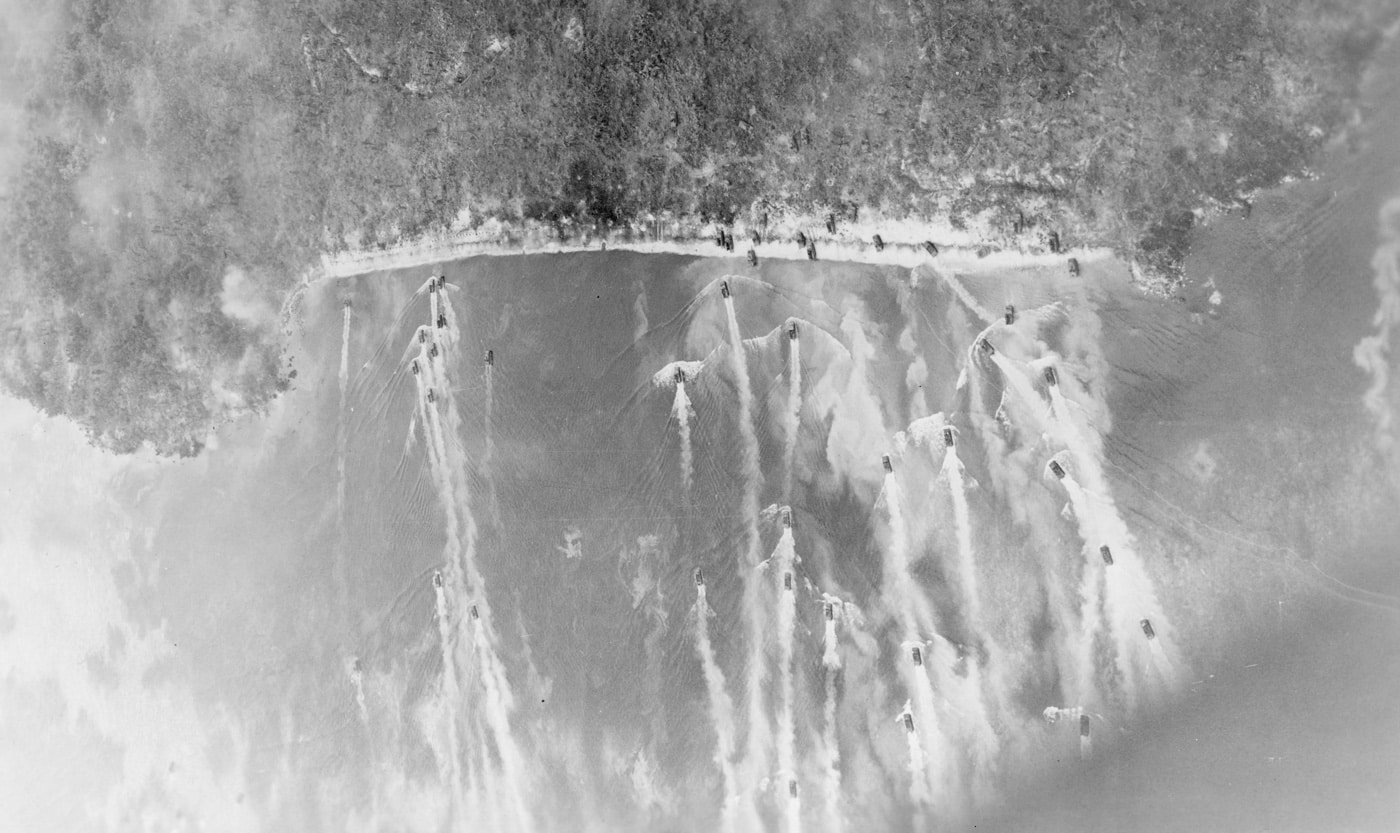

From the air, Peleliu most resembles a big lobster claw with pincers pointed northeast. From a boat cruising just beyond the island’s fringe reef, I got a landing force perspective of the actual beaches on the southwest end of Peleliu. Those beaches were designated in 1944 as White 1 and 2 on the left or northern end and Orange 1, 2 and 3 to the right or south. Windswept rows of tall coconut palms crowded the sandy stretch of just over 2,000 meters, where the 1st MarDiv came ashore with three regimental combat teams in line abreast.

The 1st Marines (Puller) would land on the left flank over White Beaches 1 and 2. The 5th Marines (Col. Bucky Harris) would land in the center sector over Orange Beaches 1 and 2. The 7th Marines (Col. Herman Hanneken) were on the right flank landing over Orange Beach 3. The basic scheme of maneuver was simple and fairly straightforward. Come ashore, establish a beachhead, advance to take the airfields a short distance inland, then wheel left or north, driving Japanese forces from all positions along the way. As usual, the Marines would find it much simpler said than done.

The landing on Peleliu plan and basic scheme of maneuver were approved by 1st MarDiv CG Major General William Rupertus, who believed the Peleliu operation would be a relative cakewalk lasting no more than a few days or a week at most. Glassing Peleliu to the north of the landing beaches, I found it hard to believe any commander would have made that kind of prediction. Looming over the island like the spiky spine of some mythical dragon was the Umurbrogol Mountain range, a coral and limestone massif where Japanese defenders had created hardpoint defenses like termites infesting a rotted tree stump.

The native skipper nosed our boat ashore on White Beach 1 where I wanted to get a close look at the murderous coral formation Puller’s 1st Marines called The Point. That little promontory overlooking the otherwise ruler-straight landing area had allowed Japanese gunners to pour enfilading fire up and down the landing beaches. It was a memory that brought shudders to my friend the Master Gunny when he talked about it. I wanted to stand on that ground where K/3/1 had nearly been wiped out on D-Day in September 1944.

Stepping ashore on pristine white sand, which reflected tropical sunlight in stifling waves of damp heat, it was quickly obvious why water would have been such a precious commodity on Peleliu. Several reports indicated that what water came ashore to refill Marine canteens arrived in cans and barrels previously used to carry aviation fuel. It was tainted, nearly unpotable, and that added to the misery of the men slugging it out on the island.

But Peleliu, to a post-war visitor, presented a sleepy, peaceful scene unlike what the landing forces would have encountered when fringing palms were shattered by fire from battleships and cruisers offshore. The crystal-clear air here was then full of choking, blinding smoke and flame as Marines came ashore from LVTs, blindly advancing under fire.

On this day 50 years later, we could see for what looked like miles up and down the western coastal road, through the palms to the ruins of the Japanese airfield, intersected by a spikey finger of the Umurbrogol pointing at high ground to the right and bloody sites like the China Wall, the Five Brothers and Five Sisters and Death Valley. Those were places I wanted to observe closely, trying to put myself in the mindset of the men who had to assault and reduce them.

But first, as an homage to my old friend the Master Gunny, I explored The Point on the far north end of the landing beaches. With his buddies from King Company 3/1, he’d held out here against savage Japanese attack and counterattack for 30 long, bloody hours after H-hour on Operation Stalemate. The point today is simply a rugged coral ridge rising some 30 feet above the level of the adjacent landing beaches. In 1944, it was honeycombed with Japanese caves, firing points, defensive blockhouses and pillboxes.

Standing atop the ridge in the ruins and concrete rubble of a casement that once housed a 25mm automatic cannon, I could see why The Point had to be taken and held. Firing from here, Japanese defenders could sweep everything close offshore and all across the landing beaches with deadly fire. Looking at The Point from a slightly higher perspective, the way counterattacking Japanese would have seen the besieged strongpoint, it was easy to understand why only 18 men from the King Company element defending the point were still standing when they were finally relieved.

The first week of fighting on Peleliu was tough on attackers and defenders alike, but Puller’s 1st Marines were particularly hard hit. Caught in a meat-grinder as they struggled for a toehold to begin clearing the Umurbrogol, and under constant pressure from the Division CG to “continue the momentum,” by D+6 the 1st Marines were a sagging skeleton, a regiment in name only, having suffered nearly 1,800 casualties, or 70 percent of their strength either KIA or WIA.

When III AC Commander Major General Roy Geiger visited the struggling 1st MarDiv, he was more than a little upset and demanded that what was left of Puller’s regiment be relieved and evacuated to a rest camp on Pavuvu in the Solomons. Much to General Rupertus’ displeasure, the Army’s 321st Regimental Combat Team of the 81st Infantry Division was brought to Peleliu from Angaur to replace the 1st Marines as the Allies struggled up into the Umurbrogol mountains, steadily pushing north against stubborn Japanese defenders.

Surveying the Field

While the scars of war on Peleliu are overgrown by a dense carpet of tropical vegetation, there are still plenty of relics lying around untouched by natives who earn a few dollars from vets, history buffs or SCUBA divers who infrequently visit the island.

Late in our stay, I was exploring Ngesebus just north of Peleliu and the site of a secondary Japanese airfield when I literally bumped into a complete LVT, rusting where it was disabled or abandoned but still mounting a pair of M1919 .30 caliber machine guns in pintle mounts.

By D+14 Marine aircraft, primarily F-4U Corsairs, were operating from Peleliu’s captured airfield. When 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines staged a textbook amphibious assault led by tanks and LVTs from Peleliu across about 350 meters of water to reach Ngesebus, they were covered by aircraft from Marine Fighter Squadron (VMF)-114, marking the first time in the war that a U.S. Marine amphibious landing was supported entirely by Marine aviation. The flight time from Peleliu to Ngesebus was so short that the pilots didn’t even bother to raise their landing gear before rolling in on targets.

Back on Peleliu, it was low tide when we ducked into a large cave in the Umurbrogol foothills. Rocks surrounding the entrance still bore scorch marks from a backpack flamethrower or perhaps one mounted in a tank or LVT.

Marine demolition squads were in heavy demand on Peleliu armed with satchel charges and backed by flamethrowers. They operated by a simple if dangerous creed: Blast ‘em, burn ‘em and then blast ‘em again to seal the deal with rockslides.

Other than flame weapons and high explosive charges, the preferred method of reducing the rabbit warren of enemy bunkers and fortifications on Peleliu was with direct fire, flat-trajectory weapons such as the 2.36” bazooka, rifle grenades or the ill-conceived T-20 60mm mortar projector, which stood some chance of putting a round through a firing slit or embrasure. High-angle fire from standard mortars or howitzers was less effective against coral and concrete reinforced positions. And there were hundreds of those on Peleliu.

Another cave complex near the Five Sisters area of the Umurbrogol was long, cramped and circuitous with a low overhead composed mostly of squirming bats that hung from the limestone. The damp coral floor was littered with cartridge cases, rotting Japanese equipment and other detritus, including a case of grenades and a knee-mortar that looked as if would still fire if someone was interested in chipping away the rust.

Most of the caves we explored were similar. In just a few hours, I picked up a fairly intact Japanese gas mask in its issue bag, several canteens and a couple of Nambu machinegun magazines. How such relics resist the elements on Peleliu I’ll never know, but they do if you’re willing to explore in depth.

Native Palauans don’t mess with this stuff for the most part. Still, there is a mildewed, one-room museum fronted by the remnants of a Type 95 Ha-Go light tank towed to the site from where it was destroyed during a Japanese tank battalion’s suicidal assault on the landing forces in the late afternoon of D-Day on Peleliu.

That doomed counterattack, with infantrymen hanging on to the tank turrets, was not typical of Japanese tactics here. After-action reports note American surprise at the lack of fanatical banzai charges on Peleliu. When Japanese forces attacked this late in the war, they did it methodically, using professional fire and maneuver tactics rather than the all-out suicidal charges they engaged in during earlier battles in the Pacific.

We spent more days on Peleliu exploring the remnants of the old Japanese airfield and the hangars and structures that still remain there as a testament to the Korean, Okinawan and native laborers who built them in sufficient strength to resist artillery, naval gunfire and airstrikes that pounded them relentlessly for weeks during Operation Stalemate II.

A day prior to leaving Peleliu, I spent a few hours in the prone position overlooking the Five Brothers. I’d come up there on a long, hot hike to pay my respects to the men of my old 1st Marine Division at a monument atop the Five Brothers, but I spent a good deal of time just lying prone amidst the coral and scrub letting my imagination run, eyeing dark splotches that marked cave entrances, wondering how anyone survived brutal eyeball-range combat in such ugly conditions. No close combat is ever pleasant, as I learned in my own crucible experiences in Vietnam, but this stuff on Peleliu … this stuff must have been a frightening agony. How did anyone survive?

Truthfully, way too many did not. When the butcher’s bill was toted up at the end of the Palau campaign, the Marines had lost 1,050 killed and 5,450 wounded. The Army’s 81st Division lost 1,393 on Peleliu and another 260 killed on Angaur. The Japanese defenders at Peleliu lost an estimated 10,900 killed in action, many of them still resting in those caves near me in the Umurbrogol Pocket. Only 202 prisoners were taken on Peleliu, and of those, only 19 were Japanese. The rest were Korean or Okinawan laborers.

Their bodies were never positively identified, but most historians — American and Japanese — believe both General Murai Kenjiro, who commanded the IJA 14th Infantry Division, and his Peleliu subordinate, who commanded the reinforced 2nd Infantry Regiment, died somewhere in the fighting for the Umurbrogol Pocket.

As for the American CG of the 1st Marine Division on Peleliu, the man who predicted the whole thing would be over in a few days with light casualties? Major General William Rupertus was relieved of command at the end of the battle and sent home to run a schools command. He died of a heart attack before the war ended.

Conclusion

I learned a lot exploring Pacific battlefields and some of that found its way into the HBO mini-series which featured a couple of episodes set on Peleliu. And I understood then why my late friend the old Master Gunny did not want to talk about that particular battle.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

816

816