G.I. Ingenuity:

M1 Carbine Battlefield Modifications

August 8th, 2023

7 minute read

When the M1 Carbine (officially the United States Carbine, Caliber .30, M1) began to reach American combat units in late 1942, the handy little rifle quickly gained a reputation as the “soldier’s pet”.

And why not? The little M1 Carbine weighed just 5.8 pounds (loaded with a 15-round magazine) and was only 35.6” long. By 1942 standards, it was a semi-automatic sweetheart.

Consequently, as the Carbine quickly made its way from its intended role as a weapon for officers and specialist troops (like artillerymen, tankers, and paratroops) into the hands of the long-suffering infantrymen, the G.I.’s penchant for customization created some interesting field modifications for their new favorite rifle.

They had plenty of opportunities — there were 6.1 million carbines made during World War II, and they were issued in every combat theatre.

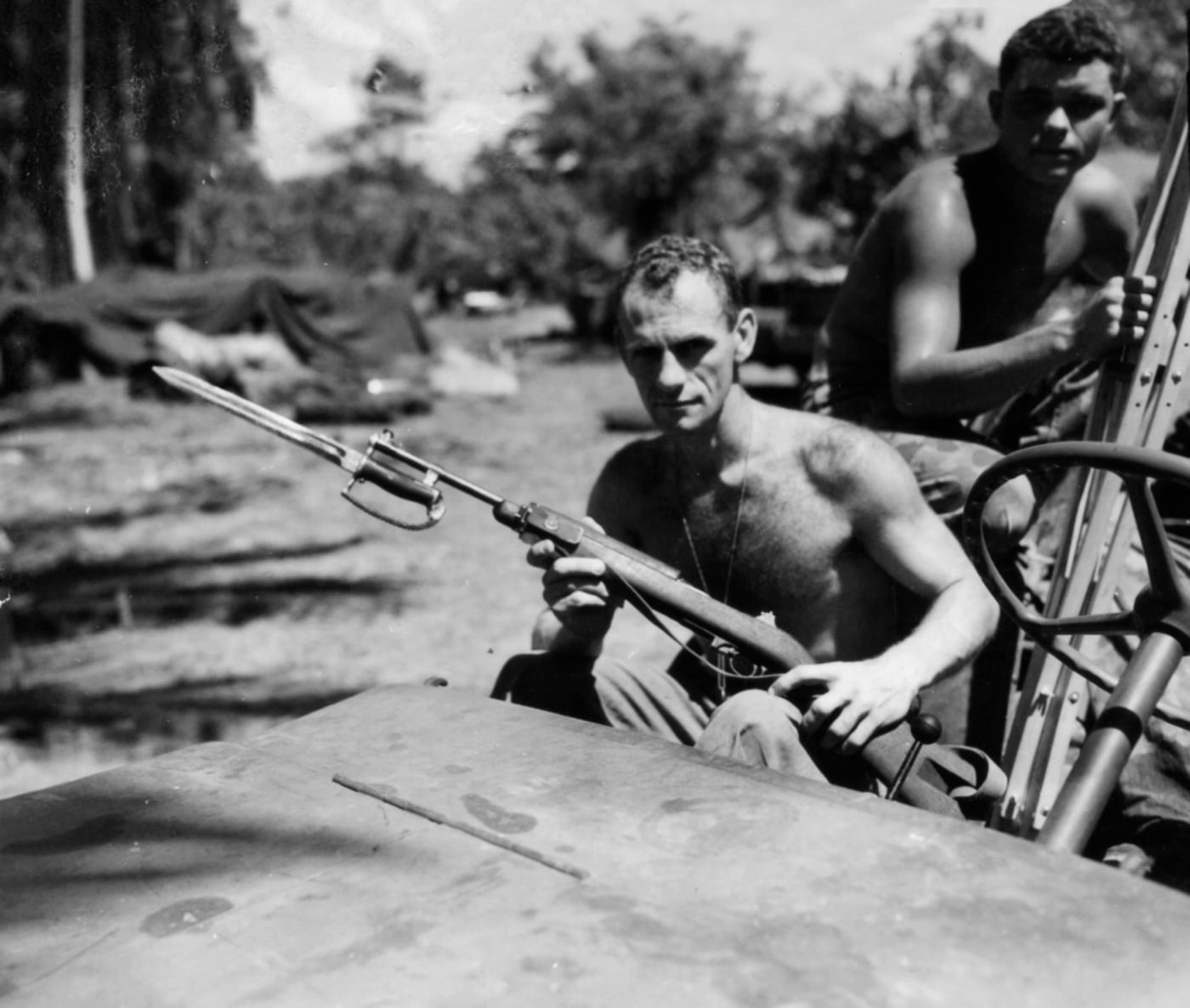

Bayonets

M1 Carbines equipped with a bayonet lug did not appear until the final weeks of the war, but that doesn’t mean that American troops weren’t creating their own bayonets for the Carbine in the field.

Ultimately, the M3 fighting knife was transformed into the M4 bayonet for use on the M1 Carbine. The official design appears to follow along with improvised bayonets created in the field.

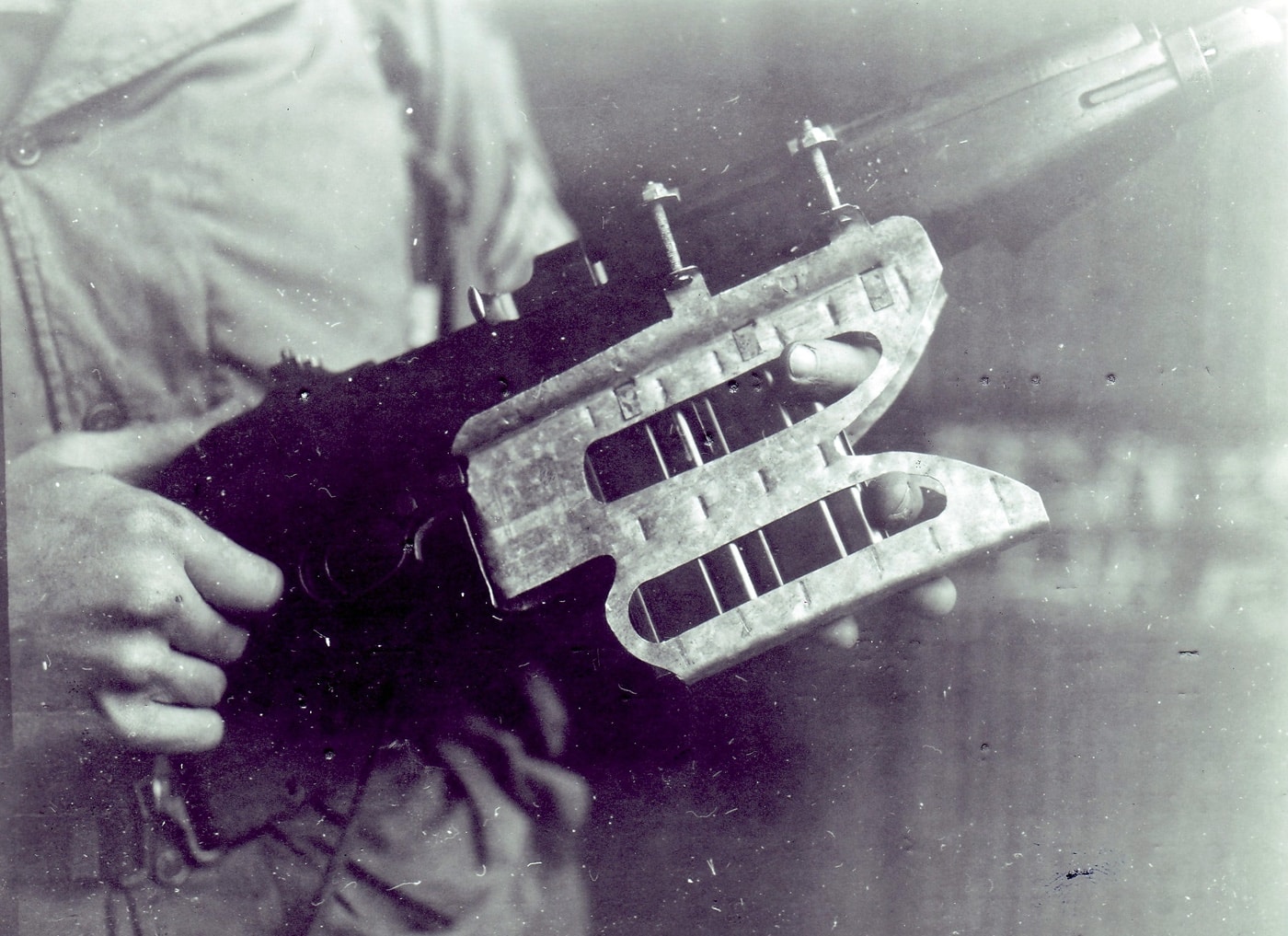

Flash Hiders

During the war, the T23 (later designated M3) flash hider was developed for use with the M3 Carbine and its infrared sniperscope. Only a handful of the M3 Carbines saw service by the war’s end, and consequently few of the M3 flash hiders were in use until the Korean War.

Even so, I managed to find a pair of photos of a field-made flash hider from an Army unit in the Philippines. Different units experimented with flash hider/compensator combinations for their carbines, the flash hider for use in close-quarters night fighting, and the compensator for Carbines field-modified for fully automatic fire.

The Clip Carrier

By late 1944, the twin-magazine “stock pouch” was fitted to many carbines — giving troops quick access to three 15-round magazines without using an ammunition belt. In the spring of 1945, a semi-official “clip carrier” was introduced in small numbers in Germany.

The unusual ammunition clip carrier allowed three additional 15-round magazines to be carried forward of the normal 15-round magazine in the mag-well (60 rounds total).

he U.S. War Department’s “Combat Lessons No. 8” describes the device:

This ammunition clip carrier was designed by T/4 Pierce S. Priest, for use with the .30 caliber carbine M1. When the carrier is fully loaded, the exhausted clip is removed in the usual manner and a fresh clip placed in position for insertion by pressure exerted with fingers of the left hand at the front of the carrier. When the carrier is partially loaded, operation is the same except that the fingers of the left hand are inserted at the side of the carrier.

Cut-Down Carbine

Units with access to tools often experimented with converting an M1 Carbine to full-auto fire. Likewise, the already small carbine was sometimes cut down even further to create an oversized pistol, or machine-pistol.

During the 1960s, both Iver Johnson and Universal created commercial variants of the M1 Carbine cut down to pistol length for sale in the USA. It seems likely that the G.I. field modifications were popular enough for postwar manufacturers to “productize” them.

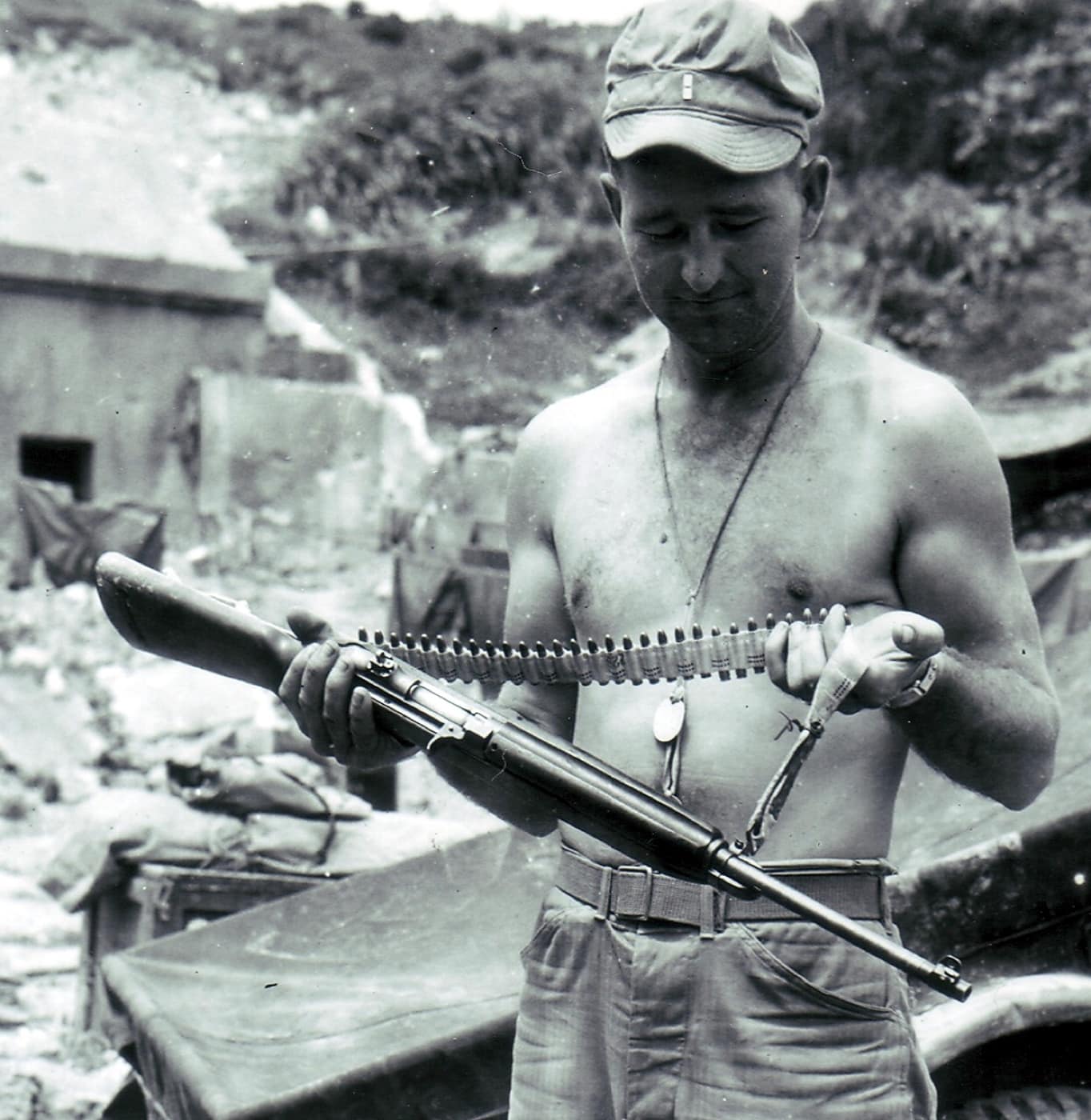

Bandolier-Sling

As a photo researcher, I can tell you that I often find interesting images of firearms modifications or adaptations that ask more questions than they answer. Back in 2006, I published a photo study of the M1 Carbine in action. In that book, I included a couple of photos that showed Marines on Okinawa with a unique sling that doubled as a bandolier for their Carbines. I didn’t say much about it in the captions, as I had no reference to describe specifically what it was.

In the summer of that year, I sat down with renowned gun researcher Dolf Goldsmith. Dolf looked at those images, and quickly asked that a box of .30 Carbine cartridges along with the web ammunition belt for a Browning M1917 .30 caliber machine gun be brought to him. With both of those in hand and an M1 Carbine on the table, Dolf broke down the “mystery sling”.

The Marines had used a web ammo belt (for the .30 cal M1917 machine gun), and the .30 Carbine rounds held in there perfectly. The newly made sling did the same job as the standard type, while providing the user with about 30 rounds of loose ammunition. All of the materials were readily available, and the conversion was relatively simple to complete.

The next expert I talked to took in all the available information, and then shot back some questions that I could not answer. I reviewed the bandolier-sling photos with the leading M1 Carbine expert, the late Larry Ruth. After a little thought, Larry had this to say: “I think you and Dolf have figured out what it is and how it was made. That makes perfect sense. But I wonder why it exists at all?”

Solving the Mystery

Apparently, the bandolier-sling concept intersected with some research that Larry was conducting on M1 Carbine magazines. Then he hit me with another question: “In all your photo research and collecting, have you found any images that show empty carbine magazines laying discarded on the battlefield?” I thought about it a bit and concluded that I had not.

Larry went on to explain that although there were millions of spare magazines made for the Carbine during the war — enough that individual magazines should have been expendable. Even today, you can find examples of 15-round magazines that are still unopened in their factory wraps. Larry went on to say that he had not seen images that showed discarded carbines mags, and furthermore, he had no anecdotal evidence of empty Carbine magazines treated as disposable by Marines, or G.I.s, or anyone. I asked several WWII combat veterans that used the M1 Carbine, and all that any of them could remember was that when a carbine magazine was empty, they put it in their pocket to eventually reload and use it again.

It was the mathematics of production and distribution of M1 Carbine magazines that wasn’t adding up for Larry. The fact that U.S. combat troops went to the time and trouble to create a sling that doubled as an ammunition bandolier (particularly late in the war when production was at its peak) appeared to be a symptom of a U.S. Ordnance problem with distribution.

The concept of a bandolier-sling would never have come up if American combat troops had enough Carbine magazines that they could confidently discard the empties in a firefight. It seems like a minor point, but it was next-level thinking on Larry’s part, and it also showed that American troops could invent tactical-level solutions for strategic-level problems. Also — spoiler alert — we won the war, so it is unlikely that anyone bothered to investigate it after August of 1945.

In the years after, I have found more images of the carbine bandolier-sling, and while all of them are shown on rifles in the Pacific Theater of the war, not all of them were taken by Marines. Army units used the same modification. This modification may have been used in the ETO or MTO, but I have no photographs to prove it.

Conclusion

So there you have it, a round-up of some of the more interesting adaptations applied to the M1 Carbine by troops in the field. Necessity is truly the mother of invention, and Americans have always acquitted themselves well when it comes to creativity in times of need.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

646

646