Best Rifle Scope for Deer Hunting

September 27th, 2021

9 minute read

Looking for a new rifle scope for the upcoming deer season? Here are the most important features to keep in mind. Want to adjust and zero any scope for faster, more accurate shots — or update yourself on reticles, mils and range-compensating scopes? These tips from 50 years of deer hunting will help you make that crucial shot when a buck appears opening day!

A Brief History of Rifle Scopes

Rifle scopes pre-date the Civil War. The first scopes were barrel-length tubes with small, dim fields and fragile innards. While they don’t have the same quality of modern optics, they were an improvement over standard sights.

Zeiss listed a short “prism” scope around 1904, soon after the J. Stevens Tool Co. began building scopes stateside. A few years down the road, U.S. scope-makers proliferated during the Great Depression. More people taking to the field to feed their families with deer meat might have played a role in this.

Bill Weaver invented his Model 330 in 1930. The 10-ounce 3x sight had a 3/4-inch steel tube and internal W/E (windage/elevation) adjustments. It sold for $19. While that sounds like an extraordinary deal, in today’s dollars that would be a little more than $300. That’s still a good price for a quality optic.

By the time Weaver rolled out the Model 330, Zeiss acquired Hensoldt and offered variable power scopes. Soon thereafter a Zeiss engineer found coating lenses with magnesium fluoride made images brighter. Fog-free scopes arrived shortly after WW II, at Leupold & Stevens. Scope prices had moved little since the ’20s.

Until the 1950s, adjusting W/E dials sent the reticle out of the field’s middle. To keep it centered, engineers placed the erector pivot at the tube’s rear, where the reticle was. In 1962, a year after Leupold announced its Vari-X 3-9x, Lyman began fitting All American scopes with Perma-Center reticles. I began deer hunting a few years later. The most popular scope of that day was Weaver’s K4, a 9-ounce, $45 optic that had appeared in 1947.

Scopes have since grown bigger, heavier, more powerful and more complex. This is not always a good thing for deer hunting rifles. While improved optics are always welcomed, the cost — both in terms of price and weight — can push them out of consideration by many hunters.

Swarovski recently announced a 5-25x52mm scope with a fat 40mm tube. The 38-ounce dS is a feature-laden laser-ranging sight with “digital intelligence.” A heads-up display shows ballistic data (downloaded from your smartphone) relevant to each shot. Pressing a button on the eyepiece puts a lighted dot where your bullet will land, the dS having factored in not only distance, but air pressure, temperature, and shot angle.

Such optics drain savings accounts. While hunting rifles list for five or six times what they did in the 1960s, scope prices have vaulted through the four-figure barrier into the stratosphere.

The Foundation

Before raiding Junior’s college fund to give your rifle new glass, think of how it will actually help you harvest deer this hunting season. Some features have little utility. Some can even limit your success.

Every scope worth owning has coated lenses, which reduce light lost to reflection and refraction (the bending of light beams passing from one medium to another of different refractive index). These two gremlins can steal 4 percent of incident light at each uncoated glass-air surface in a scope!

Magnesium fluoride, a colorless, low-refraction compound, has given way to multiple coatings of rare earths affecting specific wavelengths. Fully multi-coated optics (every lens, several coatings) yield the brightest images.

External lens surfaces also benefit from abrasion-resistant coatings — and from hydrophobic or hydrophilic coatings that bead or “slip” water, for distortion-free aim in rain. It doesn’t matter if you stalk on the ground or sit in a treestand, the weather will always assert itself. A hydrophobic coating on the lenses can help.

Soon after the 1947 debut of its 4x Plainsman, Leupold & Stevens borrowed a Merchant Marine process to fog-proof scopes, replacing air with nitrogen gas inside. Argon is now used too. Fog-proofing is a must — and, like fully multi-coated lenses and centered reticles, is now standard in high-quality optics.

The high resolution found in modern scopes helps you distinguish detail. In good light, a healthy human eye can resolve detail down to a minute of angle, or about 1 inch at 100 yards. Magnification multiplies that level of resolution.

ED or extra-low dispersion lenses have resolution-enhancing compounds. Fluorite, an optical form of the crystal fluorspar (calcium fluoride) boosts resolution, as does fluoride glass with zirconium fluoride. These are frequently found in the best deer rifle scopes.

Glass-etched (acid-engraved) reticles are replacing suspended reticles, horsehair to spider webs. The first- or front-plane reticle, standard in Europe, is gaining traction stateside in long-range scopes. It doesn’t move with power changes so cannot cause a change in point of impact. Because its dimensions remain constant relative to the target throughout the power spectrum, the reticle quickly helps you range the target at all settings.

On the other hand, the apparent change in reticle “thickness” runs counter to what’s useful. In deer cover, magnification turned down for fast shooting at big targets up close, the reticle can be hard to see. At high magnification, targets that beg fine accuracy but are shrunk by distance may be obscured by the suddenly heavy reticle.

Rear- or second-plane reticles don’t shrink or grow and remain popular with most U.S. hunters.

Check out Richard Johnson’s article on the differences between first and second focal plane scopes.

On Target

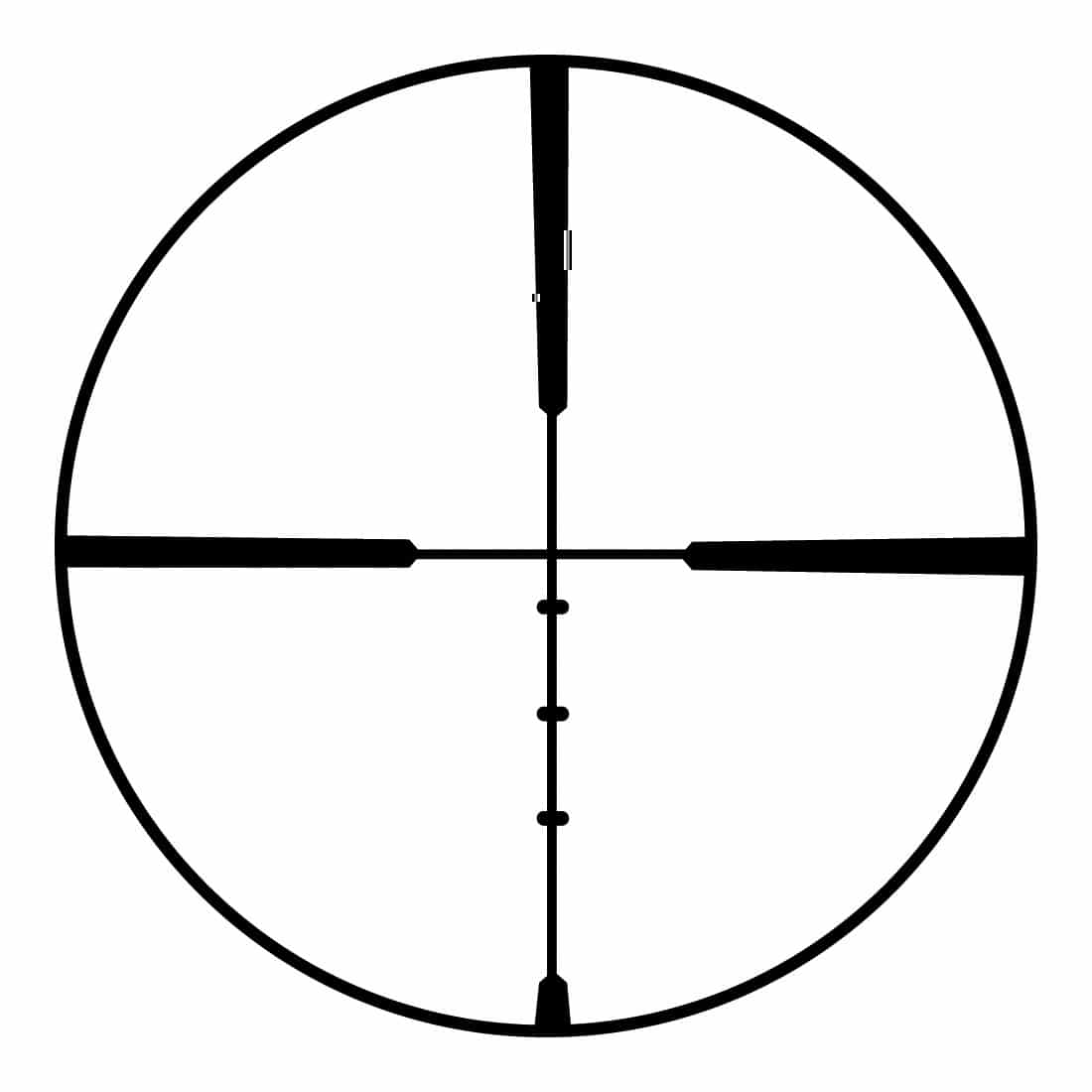

The best-selling reticle now is the “plex” (with brand-specific prefixes). Pioneered by Leupold’s Duplex, it’s essentially a crosswire with thick outer posts to catch your eye and thin center lines for fine aim.

For deer hunting, you won’t find a more versatile design.

The German #4 lacks the top post, which also suits me. Range-finding reticles with, say, three tics on the lower post to bracket distant targets, can help with long shots. But beware the busy reticle that distracts. For fast, sure aim, simple is good.

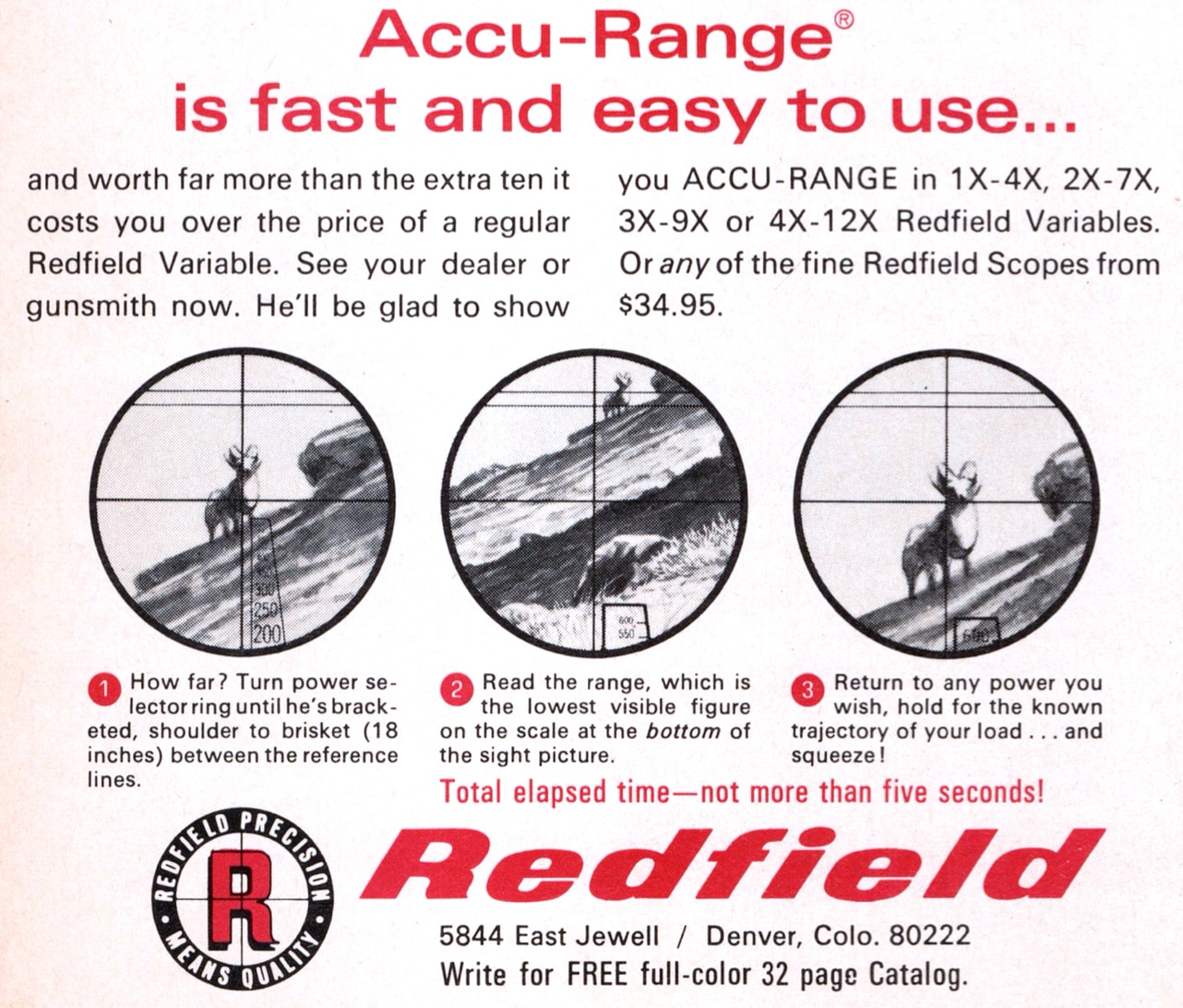

Range-compensating scopes absolve you of hold-over. The Burris Eliminator has a laser-ranging device, programmed with load data to yield a lighted aiming point for a center hold at any practical range. A Bluetooth link between external lasers and other scopes is a recent option.

In my view, the best assist for long shots is the trajectory-matched elevation dial. Many scope-makers offer one at no cost. Specify the factory load, or provide data from your handload, and the dial is manufactured so you can “dial to the distance.”

That is, instead of counting clicks, minutes or mils, you spin to the number matching the range — say, 4.5 for 450 yards. The bullet strikes point of aim. I’ve used scopes with such dials since GreyBull Precision installed one for me years ago. It’s a quick way to adjust for bullet drop, and more accurate than hold-over. No added weight, bulk or complexity in the scope.

The lust for long-range hits has fueled demand for large-diameter scopes that permit the erector tube inside more room to move, increasing range of W/E adjustment. A 30mm scope may also have larger erector lenses than does a 1-inch (25.4mm) tube, but many do not.

Dialing It In

Crisp, repeatable windage and elevation adjustments are a must if you expect to dial in the field. To check values, I “shoot around the square” on paper, 20 clicks at a time: first right, then down, then left, then up, using the same point of aim.

Quarter-minute clicks should deliver groups 5 inches apart, the last doubling the first. Resettable dials can be indexed to “0” after zeroing. A zero stop sets a travel limit, for no-look return to “0.” I seldom move dials on hunts, so don’t fret if the clicks defy reason. Dials on one of my scopes move impact 4 inches horizontally, 5 inches vertically per click! But this ancient sight holds zero. I hunt with it.

An AO or adjustable objective sleeve on the front bells of target scopes let competitors fine-tune target focus. It also eliminated parallax error — an apparent shift of the reticle when the shooter’s eye was off the sight’s optical axis. Short hunting scopes didn’t need an AO. They were typically set for parallax-free aim at 150 yards, where the target image and reticle fell on one plane inside the scope. Preventing error at other distances was as simple as centering your eye behind the scope. A turret-side parallax/focus dial has all but replaced the less-convenient AO sleeve and now appears on good hunting scopes, whose generous exit pupil at low power won’t warn you of off-axis aim.

Minutes vs. Mils

You can now get scopes with reticle graduations and clicks in either minutes or mils. A minute of angle is 1.047 inches at 100 yards, twice that at 200 and so on. Mil is shorthand for milliradian, a slice of a circle. It has nothing to do with “military,” though snipers are trained on mils.

Like a minute, a mil is an angular measure. It spans 3.6 inches at 100 yards, 3 feet at l,000. In mil dot reticles, the 3/4-minute dots on a crosswire are a mil apart. To determine range, divide target height in mils at 100 yards by the number of spaces subtending it. Result: range in hundreds of yards. If a buck 3 feet tall at the back (10 mils at 100 yards) stands two dots high in the scope, you divide 2 into 10. The deer is 500 yards away. You can also divide target height in yards by the number of mils subtended and multiply by 1,000 to get range in yards. A mil dot reticle words as range-finder at just one power setting, usually the top setting in variable scopes.

Zooming In

For decades, hunters have carried variable scopes with “three-times” magnification ranges. That is, top magnification was three times the bottom. Think 3-9x, 4-12x. Now there are five-, six-, even eight-times scopes. Engineers tell me the broader ranges add weight, cost and complexity, and make aberrations hard to control. Most wide-range variables have 30mm tubes or bigger, albeit Swarovski lists a five-times Z5 3.5-18×44 on trim 1-inch pipe.

For me, the best scope for deer hunting is a fixed-power 4x. Alas, few survive. Among variables, Swarovski’s 3-9×36 and Leupold’s 2.5-8×36 appeal to me, for their lightweight, modest objective size and practical power range. I’ve used heavier optics of superior optical quality from Zeiss, Leica and Meopta, but think a scope should not exceed 15 percent of the rifle’s weight.

Shopping for a hunting scope? Remember it’s a sight. It must leave your rifle feeling like a rifle.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

164

164