Did the M14 Fail the BAR?

March 6th, 2020

6 minute read

Most people get the BAR wrong. While the Browning Automatic Rifle is one of the most celebrated American military firearms in the history of U.S. Ordnance, it remains one of the most misunderstood weapons of all time.

The key to John Browning’s genius design is in its name. It was, is, and always will be an “automatic rifle.” Shortly after the Allied victory in World War I, new trends in infantry weapon designs led many in the U.S. Military to try to alter or replace the BAR. None of these alterations were successful, though. No bipod, carrying handle or flash hider could change this fact, and ultimately the BAR was phased out of service during the 1960s with nothing developed to replace it.

The initial BAR, the M1918, is truly a man’s gun. It is nearly four feet long and weighs sixteen lbs. Later versions added several accessories (the aforementioned bipod, carrying handle and flash hider), and the weight jumped up to 20 lbs.

The size and weight can be intimidating for some shooters, but once you shoulder a BAR and fire it on full auto, you quickly understand that it is almost perfectly balanced, and its normal weight absorbs much of the recoil of its .30-06 ammunition.

A New Direction

During the 1920s, the concept of the “light machine gun” became popular. Many military planners around the world began to gravitate to the notion of a “squad automatic” to provide a base of fire for infantry sections (all equipped with bolt-action rifles).

These early light machine gun concepts would manifest themselves as the French FM 24/29, the Czech ZB vz. 26, the Italian Breda Model 30, the Soviet DP-28 and the German MG-13. Some of these guns had quick-change barrels, others did not. All of them used a magazine of some type. The second generation of these light machine guns saw the arrival of the first general-purpose machine guns (GPMG), the German MG34 and the British Bren.

In the United States the water-cooled Browning M1917 served as the heavy machine gun. The air-cooled Browning M1919 generally defied pigeon-hole descriptions and was used for a wide range of applications. The BAR continued to serve as the base of squad firepower, albeit cluttered up with a bipod and carrying handle in a faux LMG guise.

Within its original role as an automatic rifle, the lack of a quick-change barrel and the limitations of a 20-round magazine were minor problems. Force-fit into a nebulous role as a “LMG”, the BAR was found wanting. American troops have always been noted for their ingenuity, and so they quickly adopted a “if-it-isn’t-broken-then-don’t-try-to-fix-it” approach. As World War II emerged and progressed, the BAR was gradually returned to its original state (at least in the field), with bipods, carry handles and even flash hiders discarded to save weight.

By the time the Korean War began in 1950, many of the hard-learned lessons about how to best use the BAR had been forgotten or ignored. Most of the BARs issued to troops bound for Korea were fitted with the same add-ons that had been taken off and thrown away in the previous conflict. By the end of the Korean War, most BAR gunners had again stripped down their weapons to their original configuration. The BAR performed best in its birthday suit.

A BAR, Lite

Much like the concept of the “light machine gun” was all the rage in the 1920s and 1930s, the notion of the “squad automatic” really took hold in the 1950s and 1960s. Almost every significant rifle developed at that time had a squad automatic variant: the Belgian FN, the German G3, the Soviet AK-47, Italian BM59 and the U.S. M14 are all examples of firearms that were modified and tweaked as part of this development.

As the M14 rifle was planned to replace the M1 Garand and the M1/M2 Carbine, so too was it planned to replace the BAR. In theory, the single rifle platform was an effective solution, particularly from a logistics perspective.

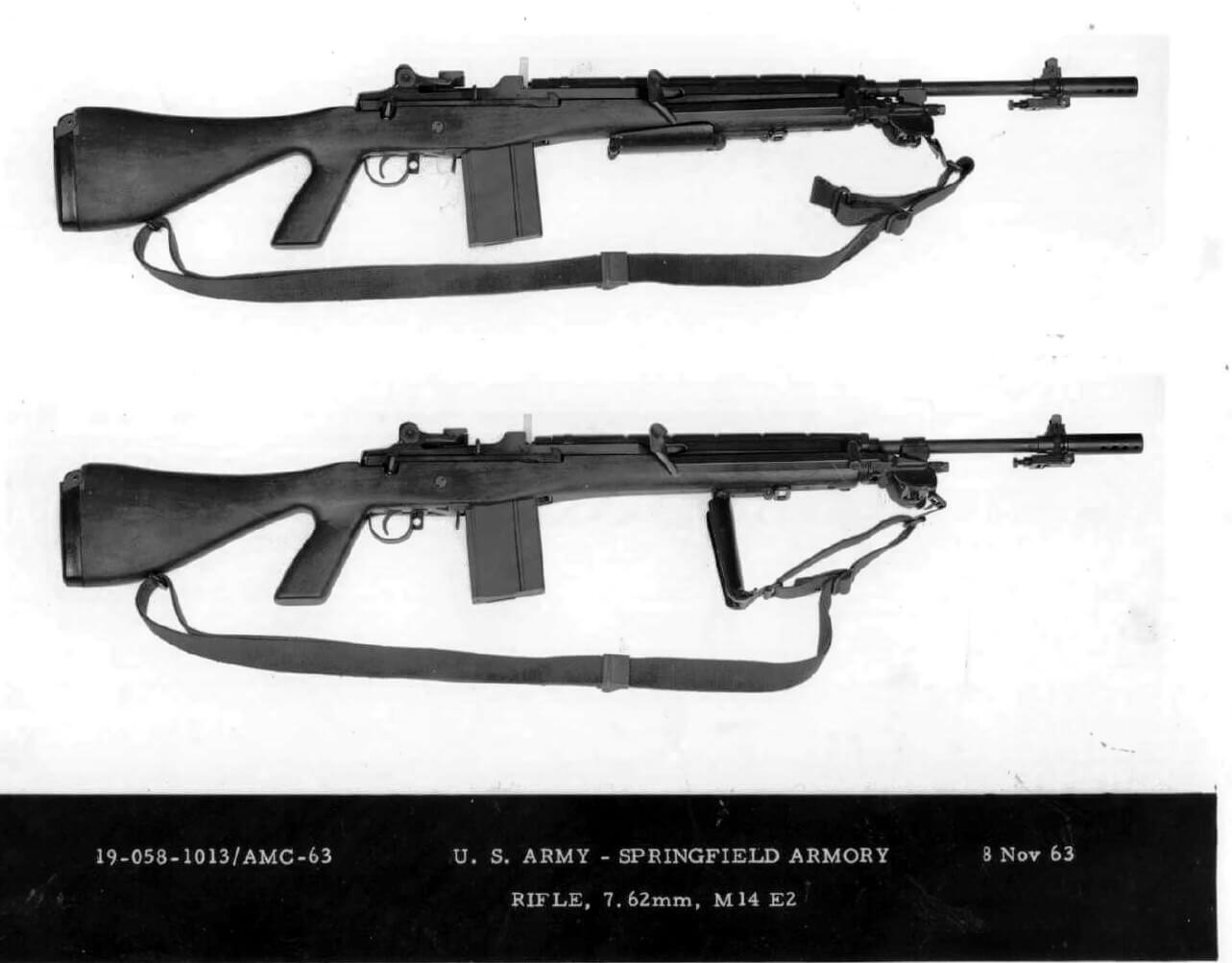

To create a squad automatic using the M14 rifle, the United States Infantry Board (USAIB) developed the M14E2, which featured an in-line stock with a pistol grip and more prominent butt, a plastic upper fore-end, an adjustable bipod, and a clamped-on muzzle stabilizer. A folding metal foregrip was fitted to help the gunner control the weapon during full-auto fire, and the stock was given a sturdy rubber recoil pad.

The Infantry Board determined that the E2 configuration was able to meet the accuracy requirement of a squad automatic weapon, placing 80% of hits in a 40-inch circle at a range of 200 meters.

Some numbers of the M14E2 (also known as the M14 USAIB) were issued beginning in 1963. Adjustments were made to better secure the muzzle stabilizer, the M2 bipod, and to strengthen the foregrip and the stock itself. All in, it weighed 14.5 pounds.

The Wrong Answer?

During 1966 it was formally adopted and designated as the U.S. Rifle M14A1 7.62mm. By that time, the standard M14 rifle had been out of production for nearly four years. Despite this, more than 8,300 M14 rifles were converted to the M14A1 standard. Of those, only a few hundred are known to have been sent to Vietnam. Correspondingly, few photos of the M14A1 in combat exist.

Apparently, the rifle worked well enough as a squad automatic, but issues with controllability on full-auto, overheating and sustained fire continued to dog the specific rifle, and the squad automatic concept in general. As such, the M14A1 quickly faded away. It seemed that the M14 would not step into the now empty role formerly filled by the famous BAR.

But it was likely an unfair attempt to make the M14 into this in the first place. A truly fine rifle that performed well in its intended role, the M14 was simply too svelte to truly be a squad automatic. And those characteristics are what make the Springfield Armory M1A, the civilian-legal sibling of the M14, such an appealing option for U.S. civilian consumers.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

211

211