Don’t Let Perfect Accuracy Kill You

January 27th, 2022

6 minute read

Accuracy can be defined as a state or quality of being exact or precise. No matter the shooting discipline we are involved in, we want our firearms to be accurate enough for the task at hand. Depending upon the context in which the firearm will be used, there is a great disparity in performance potential. For example, a very high-end .22 caliber target pistol will no doubt exhibit much greater accuracy potential than a pocket pistol or a snubbie revolver.

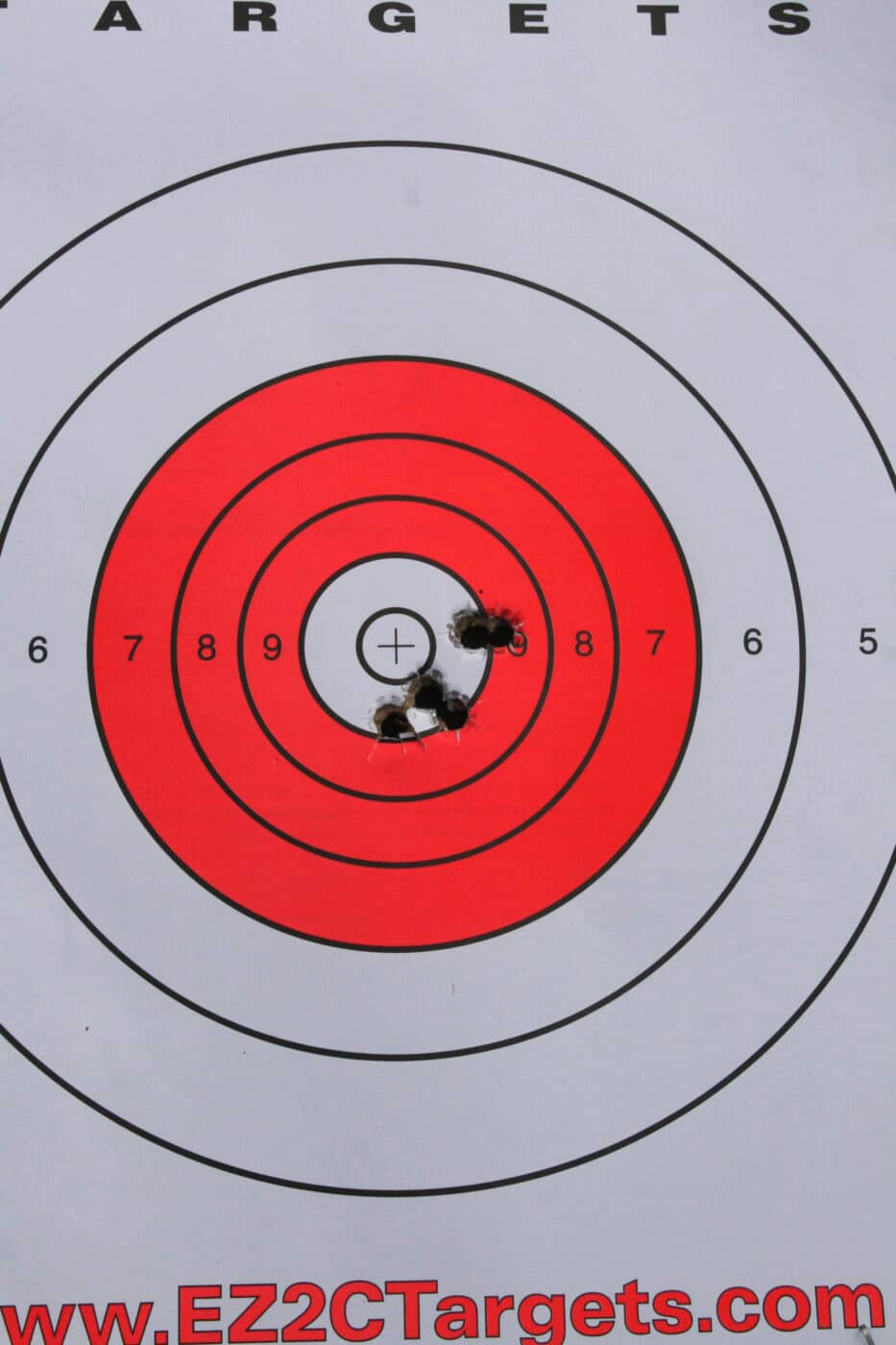

To my thinking, accuracy is a relative term. For the serious target shooter, only a tight cluster of hits in or around the X ring of that B8 target is going to make the cut. That high-value area is significantly smaller than the A-Zone of an IPSC target commonly used in practical pistol competition, where the time allotted to shoot a specific string of fire is compressed. Without question, available time is a big factor in determining whether or not we can place our hits where we want. Although the accuracy potential of our firearm doesn’t change, human performance begins to degrade when we start pushing down on the gas pedal.

Time is indeed the 800-lb. gorilla in the room in any discussion about making effective self-defense hits. In most target shooting disciplines, and for that matter most police qualification courses, time frames are generous and allow plenty of time to line up the sights and apply a perfect trigger press. Real-life defensive shooting isn’t nearly as accommodating. The fact that you are probably playing “catch up” with an adversary who has already initiated some sort of aggressive action is a huge disadvantage, and the need to quickly make defense-effective hits is readily apparent.

But where do I need to place those hits? And exactly how fast do I need to be? Those answers might be best found taking a hard look at human anatomy and those two-dimensional paper targets we train on.

Stopping the Threat

When shooting in defense of life, our goal is to quickly place decisive hits on the aggressor in a location where it will prevent him from continuing his assault. The most reliable area to achieve a reasonably fast stop is to place multiple hits in the high chest area. Sure, one shot may do the trick but despite great strides in the effectiveness of ammunition, handguns aren’t especially decisive stoppers and more than one hit may be required.

So why shoot for the high chest? Wouldn’t a headshot be a better bet? Frankly, headshots are an “iffy” proposition, to say the least. I know of multiple instances where a bad guy has taken more than one hit to the head and kept on fighting. The rounds either deflected off the skull, or it struck non-vital areas and didn’t drive into the brain. Heads are also very difficult targets to hit, especially when you factor in stress and movement.

On the other hand, the chest is a relatively large area and contains the vital organs that support life. Should you introduce serious trauma to the heart, lungs and major blood vessels by delivering multiple shots with your pistol, the likelihood of stopping the threat is high. Unlike on television or in the movies, you adversary will not instantly stop fighting, but there is a pretty high likelihood they will no longer be in a position to hurt you.

The bottom line is that it is impossible to predict with absolute certainty what effect a bullet strike will have on an aggressor. Hits to the heart/lung area will typically result in rapid incapacitation. However, there are numerous documented instances where an attacker has sustained mortal injuries but is able to stay in the fight. But when it’s all said and done, multiple strikes in the high chest area afford the best odds of success.

Targets Matter

The targets we utilize in our training should to a certain extent, reflect reality. Many popular silhouette targets feature an oversize “high value” or place it in the wrong location. Others, like the original FBI Q target, have no designated high-value area and a hit on the bottom edge is scored the same as a hit in the chest. As a result, shooters who fire an exercise on these less-than-optimal targets come away with a high score and a vastly inflated idea of their skill level.

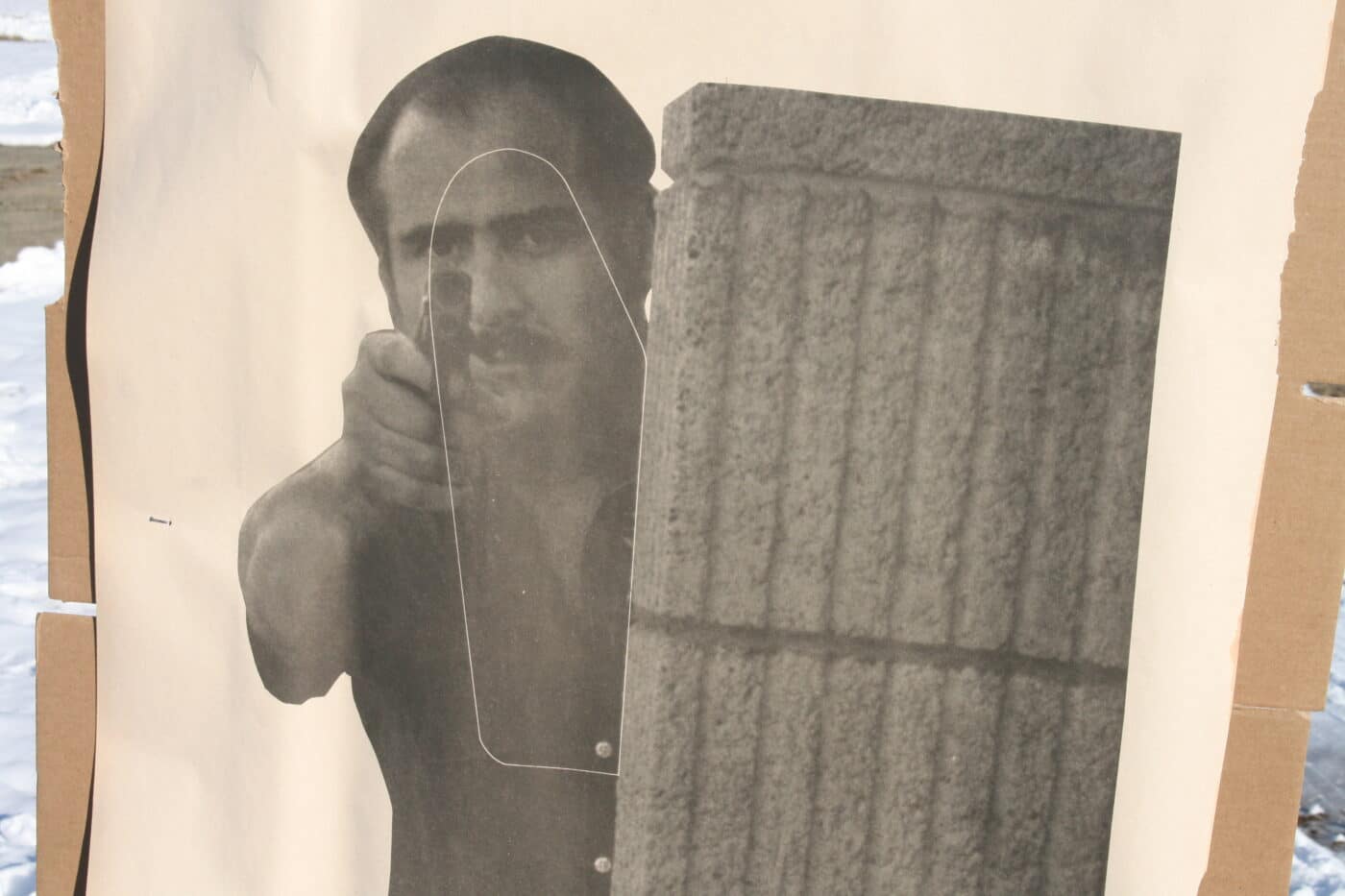

The good news is that there are all sorts of targets out there that better represent the human form, complete with a realistic size high-value area. Bear in mind that this area really isn’t that large. For years, I have used IPSC targets in my training and, while not perfect, the A-zone does emphasize a greater reward for hits in the center chest. On occasion, I also use photographic silhouettes that feature a subject, a partially exposed subject or one with the body bladed to make that high-value area an even more difficult target.

With just a little bit of imagination, you can create your own targets with a high-value area. Printable anatomy overlays can be found on the internet and affixed to any cardboard or paper target. Other range props I have used include 8” paper plates, B-8 centers, and even 3”x5” index cards. Don’t settle for mediocrity! The formula for success remains reasonably quick hits into the area they will do the most good.

Train to Prevail

Placing a tight knot of hits on a target from typical self-defense distance is no special trick. However, doing it at speed is another matter altogether. Not only do we have to hit, but the shots have to be placed with a degree of precision so they can do the most good.

A number of elements factor into our ability to make quick hits, including distance, size of the target area, movement, mental state, and skill. Since we have a bit of control over it, let’s consider skill first. For some time, I have used a simple “step back” exercise to get both new and experienced shooters dialed in. I begin a mere 5 feet or so from the target, and the pistol is drawn to the ready position. On the command, the shooter fires a three-shot burst with no time limit. Are all the hits in the high-value area? Good. Now, take a step back and repeat. I take it back to about 10 yards and, if we have met with success, I have the shooter come back up close and now add a time element. Can we fire three shots in three seconds for all hits? How about two seconds? As distance increases, shooters will typically slow it down just a shade to ensure good hits. If we continue to meet with success, you can reduce the time, change the number of shots to be fired, or draw from the holster. This drill isn’t especially difficult to run, nor does it require a great deal of ammo. However, it will give you some insight into your skill level.

Conclusion

Unlike the range, a real-life threat may be moving and present a much more challenging target. Extreme stress can also play havoc with your ability to precisely place hits on a threat. I would submit that point shooting or stance-directed fire will allow you to place decisive hits on a target just a few yards away, but success falls off dramatically once distance increases or the threat is only partially exposed or moving. One of the major advantages of miniature red dot sights is that your focus can remain on what is unfolding in front while you superimpose the red dot on the threat and get a reliable point of aim. So that is something to consider.

Set the bar high in your training and don’t settle for just “good enough”. Your ability to place decisive hits on an aggressor at typical self-defense distances will determine who survives the fight.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

383

383