Everything You Need to Know About the M1 Garand

January 12th, 2021

10 minute read

My father was a combat infantryman who fought from Normandy until the end of World War II in Europe. Most of my uncles were also combat men. So too were several of my neighbors in the little town where I grew up. A few of my teachers were combat veterans as well. The Second World War had a massive impact on the United States, and consequently on America’s culture. And the iconic M1 rifle was well known by most folks, kids and adults, civilians and veterans alike.

People talked much more about firearms then, while not necessarily about their use in the war, but it was much more of a common topic. It is also important to note that 20th century military firearms were not hot “collectibles” at that point. Some folks did collect them, but there weren’t so many outlets to find them, nor the fierce competition to acquire them like you find today.

In that era, if you had questions about the M1 Garand rifle, you likely had a primary source of information close by. All you had to do was ask. Today, it isn’t so easy. The M1 rifle is now a prized collector’s item, and even with more information about it available than ever before, some of the basic facts have become obscured by 80 years of myth and misconception. So let’s dive into the story of the M1 Garand.

The Man Behind the Legend

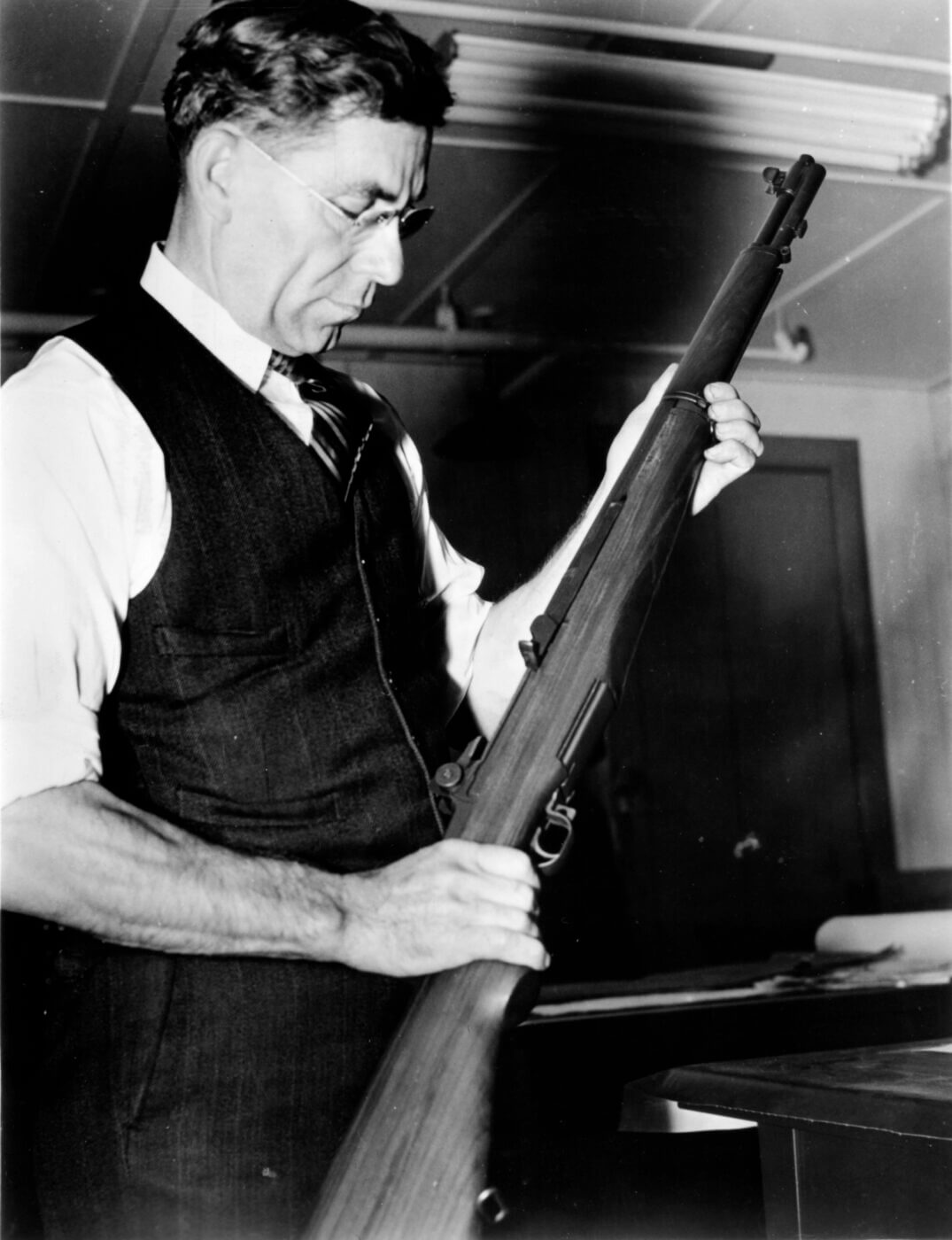

The creator of the M1, John Garand, was born in Quebec, Canada in 1888. He moved to the United States in 1909 and became a naturalized citizen in 1920. He began working for Springfield Armory as an engineer in 1919 and remained there until he retired in 1953. Garand designed the M1 rifle and then ceded all rights to the weapon to the U.S. government during 1936. So even though there were millions of M1 rifles made, John Garand never received any royalties for his famous design. Talk about being a team player!

You will hear various pronunciations of his last name, but according to family members and close friends, his preferred pronunciation of “Garand” rhymes with “errand”.

What About the Carbine?

Eighty years on from World War II, U.S. military nomenclature of the war era often adds to the confusion of modern shooters and collectors. In the rapid-fire discussion overheard at gun shows, the term “M1” is sometimes used so frequently that even experts ask for a time-out for clarify. When you consider that there is an M1 Rifle, an M1 Carbine, even an M1 helmet, the language used to describe the equipment of the era often stands in the way of clear communication.

The M1 Rifle is chambered in .30-06. It is a big firearm at 43.5″ long. The M1 Carbine is also chambered in .30 caliber, but it uses a significantly smaller cartridge — the .30 Caliber Carbine. The M1 Carbine is much smaller, just 35.6″ long.

The two rifles are not related — the M1 Carbine is not a shortened version of the M1 Rifle. The M1 Rifle was adopted as the standard U.S. service rifle in 1936. The M1 Carbine was born during World War II and standardized in 1942.

The M1 Garand is the first model of its type (semi-auto rifle), and thus the “M1 rifle” designation. The M1 Carbine is also the first model of its type (semi-auto carbine), and so it also gets an “M1” designation, in this case followed by “carbine”.

Many of us like to abbreviate, we feel like it makes communication simpler, and in most cases it does. However, when discussing the M1 anything, it can make the conversation confusing. In any event, you’re never wrong to ask for clarity, or to use some extra words to make sure you are understood.

The Carbine’s original purpose was to replace the pistol and the submachine gun in U.S. service. Ultimately, the Carbine was made in massive numbers, but it never replaced anything; the U.S. military simply added it into an already crowded mix. Along the way the M1 Carbine proved to be a fine little weapon, but it remains one of the least understood American military firearms of all time — even during World War II and Korea, some troops overestimated the M1 Carbine’s capabilities by expecting it to match the M1 Rifle’s level of range, accuracy and hitting power.

Why the M1?

At the end of World War I, the U.S. military possessed two of the finest battle rifles in the world: the M1903 Springfield and the M1917 Enfield. Both were bolt-action rifles, chambered in .30-06. U.S. Ordnance chose to put the M1917 rifles on the shelf and concentrated on producing and issuing the M1903 to all branches of the service. American infantry firepower was in fine shape.

Even so, U.S. Ordnance looked forward. At Springfield Armory, John Garand was tasked with developing a semi-automatic rifle as early as 1919. Development continued throughout the 1920s, and the U.S. Army became interested in a new 7mm (.276) cartridge. Competing designs were submitted by Thompson, Pedersen, Colt-Browning, Browning and Bang. No clear winner was established after multiple tests.

In February 1932, the Secretary of War ordered all work on semi-auto rifles in .276 abandoned, and development efforts focused on the Garand rifle in the U.S. standard .30 caliber. The “US Rifle, caliber .30, M1” went to field trials in May 1934, was cleared for procurement on November 7, 1935, and then formally adopted and standardized on January 9, 1936. America had the first semi-automatic rifle as its standard infantry rifle.

En-Bloc?

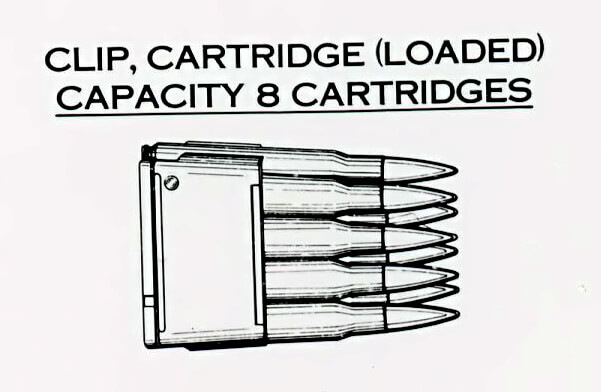

The M1 rifle has an internal magazine that is fed by an 8-round en-bloc clip. This one feature is the main source of confusion and complaints about the rifle. In the modern era, this clip-loading system seems cumbersome and limited. But John Garand’s design was in response to U.S. Ordnance requirements for a fixed, non-protruding magazine. A detachable magazine was considered to be too easily lost or damaged, and the magazine well offering too easy an entry point for dirt and moisture. At that time, some also considered a protruding magazine to be a hindrance to prone position firing.

So, the M1 Rifle has the blessing, and the curse, of being the first semi-auto rifle adopted for service. Remember we are talking about a rifle developed during the 1920s — our current expectations of a military rifle are so high because the M1 design worked so well back then.

Certainly, the en-bloc clip has its drawbacks. Once loaded, the M1 rifle’s magazine is difficult to “top off”. Some folks think that the M1 cannot be easily unloaded, but this is not true — the clip latch button will eject fully or partially loaded clips with the action held open. Without a clip, the M1 can only be loaded with single rounds.

The thin metal clips are not difficult to load, but they take a bit of time. Chasing after an ejected clip and then re-loading it in combat was certainly not easy or desirable, and fortunately American logistics provided most troops with enough pre-loaded M1 clips, usually distributed in bandoleers.

The distinctive “ping” heard after the last round is fired and the clip is ejected was the source of some discussion during the war, and then in strange folklore about the M1 rifle ever since. Claims have been made that some U.S. troops were killed because their enemy knew they were out of ammunition after hearing the sound of an M1 clip ejecting. However, there are no documented cases of any American warrior killed or wounded in this type of situation.

The fog of war includes audio, and the battlefield is a confused and noisy place where the sound of a metallic ping would hardly be noticed in a firefight. Even if it was heard, how would the enemy know that the American rifleman hadn’t simply reloaded, or that his buddy wasn’t ready to cover him? The whole issue is total nonsense, but it makes for grand stories at the local gun show. Don’t let it keep you from acquiring an M1 Garand.

On the plus side, the en-bloc clips allowed the M1 to be reloaded rather quickly. Experienced troops could get off up to 50 rounds a minute of aimed fire.

M1 Thumb?

M1 Thumb is a painful experience shared by many M1 Garand shooters. It is an easy club to become a part of, and one that you will immediately wish you had not joined. M1 Thumb is the result of the bolt closing at incredible speed and smashing the user’s thumb into the receiver. For your trouble, you receive a nasty crescent-shaped blood blister beneath your thumbnail, or maybe even a cracked thumbnail. Either way, you will scream out curses, and maybe even invent some new swear words.

A Numbers Game

A little more than 5.4 million M1 rifles were made, and the lion’s share of these were produced during World War II. Production was slow until 1941, then increasing dramatically as war appeared imminent. Springfield Armory handled most of the World War II production, with a smaller amount of rifles made by Winchester. During the latter part of the Korean War, the Department of Defense increased production again, awarding contracts to International Harvester and Harrington & Richardson. The last M1 rifles were made at Springfield Armory in early 1957.

First Combat Use?

The M1 rifle debuted in combat during the defense of the Philippines, December 8, 1941 to May 8, 1942. Japanese troops were quite surprised by the level of U.S. infantry firepower, wondering how America could afford to “equip every infantryman with a machine gun.” Before the islands fell, very positive reports were transmitted to the United States about the rifle’s combat performance.

The M1 rifle’s combat debut in Europe came during the large raid on the French port of Dieppe, August 19, 1942. A group of 50 American Rangers accompanied the British commandos and Canadian troops during the raid, with some of the U.S. troops carrying M1 rifles.

Did All Troops Have the Garand?

Eventually they were, but wartime distribution was greatly varied. Most U.S. Marine Corps combat units were still equipped with the M1903 rifle well into 1943. Some U.S. Army infantry units in Italy and in the Pacific theater had a mix of M1903 and M1 rifles until 1944. After D-Day, most U.S. infantry units in Western Europe were equipped with M1 rifles, but many combat engineers, MPs, and artillery units in the same area were not. By the end of World War II, however, the M1 rifle had seen action all over the world, with every branch of the U.S. military.

In his book Shots Fired In Anger, U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel John B. George described the Marines’ desire to acquire an M1 rifle during the Guadalcanal campaign:

“During the organization of a joint Marine-Infantry patrol…I saw this Marine, a member of the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion, place and keep himself squarely behind one of the Army sergeants in the advance platoon. When the march was well underway the Sergeant inquired as to why the Leatherneck kept treading on his heels. The answer came quickly: ‘You’ll probably get yours on the first burst, Mac. Before you hit the ground I’ll throw this damn Springfield away and grab your rifle.’”

M1 Sniper Rifle?

The Army adopted the M1C as a standard sniper rifle in June 1944, but very few M1Cs saw combat during World War II. The M1C saw extensive service with Army units during the Korean War. Designated MC52 by the Marine Corps, the M1C saw some use by the USMC in Korea, and soldiered on until the early part of the Vietnam War. As for the M1D, although more than 21,000 were made, few were completed in time to see action in Korea. Both are considered to be excellent sniper weapons for their time.

What Is the “Tanker”?

As World War II progressed, there were increasing calls for a shortened M1 Rifle for use in jungle warfare as well as with the new concept of “armored infantry.” Two variations were created, the M1E5 with an 18″ barrel and a metal folding buttstock, and the T26 which featured the 18″ barrel with a standard wood stock.

Neither one was approved for production, but a few T26 were used in combat tests in the Philippines during 1945. The “Tanker Garand” is not an official term, and any M1 rifles offered today are likely postwar commercial productions. With the short barrel, muzzle blast and recoil are quite notable.

Service Life

Despite the adoption of the M14 rifle in 1958, the M1 Garand remained in limited service until 1965. Some of the early American advisors in Vietnam carried M1 rifles. The M1 remained in service with the U.S. Army Reserve, the National Guard and the U.S. Navy until the mid-1970s. The Navy used a small number of M1 rifles rechambered in 7.62x51mm NATO.

The United States also provided the M1 rifle to a wide range of friendly nations after World War II and through the 1960s: Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Columbia, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Uruguay, Venezuela, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, Israel, Iran, Turkey, Austria, Great Britain, Greece, France, Italy, Netherlands, Belgium, West Germany, Denmark, Norway, Ethiopia, Taiwan, Indonesia, South Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Philippines, South Korea and Japan.

Greatest Implement, Ever

Fresh from victory in World War II, General Patton described the M1 Rifle in glowing terms, calling it: “The greatest battle implement ever devised.” From buck private to supreme commander, the rifle’s record of achievement speaks for itself. Who am I to argue with General Patton? Even John Garand was moved to say about his creation: “She is a pretty good gun, I think.” She’s definitely good enough for me.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

291

291