Fritz X: The Nazi’s Ship-Killing Guided Bomb

November 14th, 2023

11 minute read

A forerunner to modern anti-ship weapons (ASW), Germany introduced the Fritz X guided bomb to the battlefield during World War II. These armor-piercing bombs were guided weapons mainly used against Allied ships in the Mediterranean region. However, Hitler’s precision-guided bombs could have been used to disrupt Operation Overlord in Normandy. Tom Laemlein gives us the full story on what may have been the world’s first precision guided ASW.

On the morning of September 9, 1943, the bulk of the Italian fleet left La Spezia harbor to sail to Malta where they were to surrender to the Royal Navy. The day before, U.S. General Dwight Eisenhower had announced that the Italian government had surrendered, Mussolini was in custody, and Italy was no longer a part of the Axis powers. The Italian fleet had originally planned to attack the Allied landing force at Salerno on September 9th, but the surrender changed everything. Instead of steaming into combat, the Italian battle fleet would instead sail into capitulation.

The flagship of this Regia Marina armada, commanded by Admiral Carlo Bergemini, was the massive battleship Roma. Laid down just five years earlier, Roma had been commissioned in June 1942. The massive (46,000 tons) ship carried nine 15-inch guns, and a dozen 6-inch cannons as well. She was protected by up to 13.8 inches of armor, and at full speed the Roma could make 30 knots. Her sister ships, Vittorio Veneto and Littorio sailed with her on the way to Malta. Allied naval intelligence rejoiced that the three most powerful battleships in the region would soon be off the Mediterranean chessboard.

Meanwhile, German forces in the Mediterranean were not sitting still. On September 8th, German troops in Italy, Yugoslavia, and the Balkans attacked and disarmed Italian troops, as Operation Achse went into motion. By September 19th, more than a million Italian troops had been disarmed, and nearly 30,000 who resisted were killed. Despite the Allied conquest of Sicily in August, and the invasion at Salerno on September 3rd, most of the Italian mainland was under German control. So too was much of the airspace above Italy and over the Mediterranean. What followed was to be one of the most shocking events of the war, revealing a deadly new technology, and opening a new era of ship attack.

Enter the Fritz X Bomb

World War II saw the demise of the battleship. As the power of attacking aircraft grew, the once almighty capital ships struggled to protect themselves. Early in the war, when the Luftwaffe maintained air superiority over portions of the North Sea, the English Channel and in the Eastern Mediterranean, German dive-bombers (most notably the Ju 87 Stuka) achieved notable successes against warships of the Royal Navy. But dive bombers needed air superiority to create an effective operating environment, and by the time of the Allied landings at Salerno, Italy in early September 1943, the Axis no longer completely controlled the skies over the Italian coast.

The Germans had been diligently working on new ship-strike methods that allowed the attacking aircraft to remain at a safe distance from naval anti-aircraft fire. Operating at high altitude, the aircraft would also be relatively safe from most Allied interceptors as well.

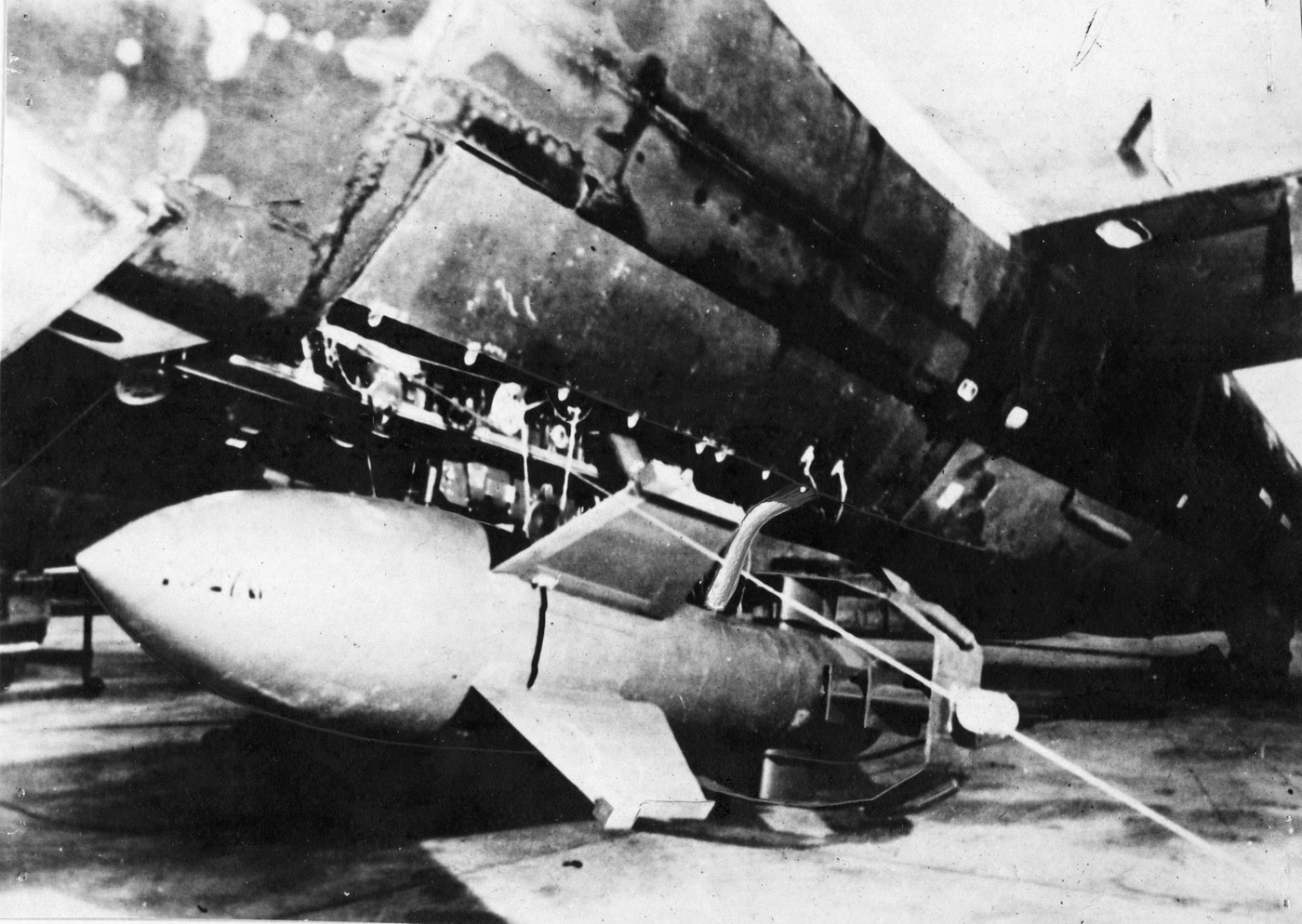

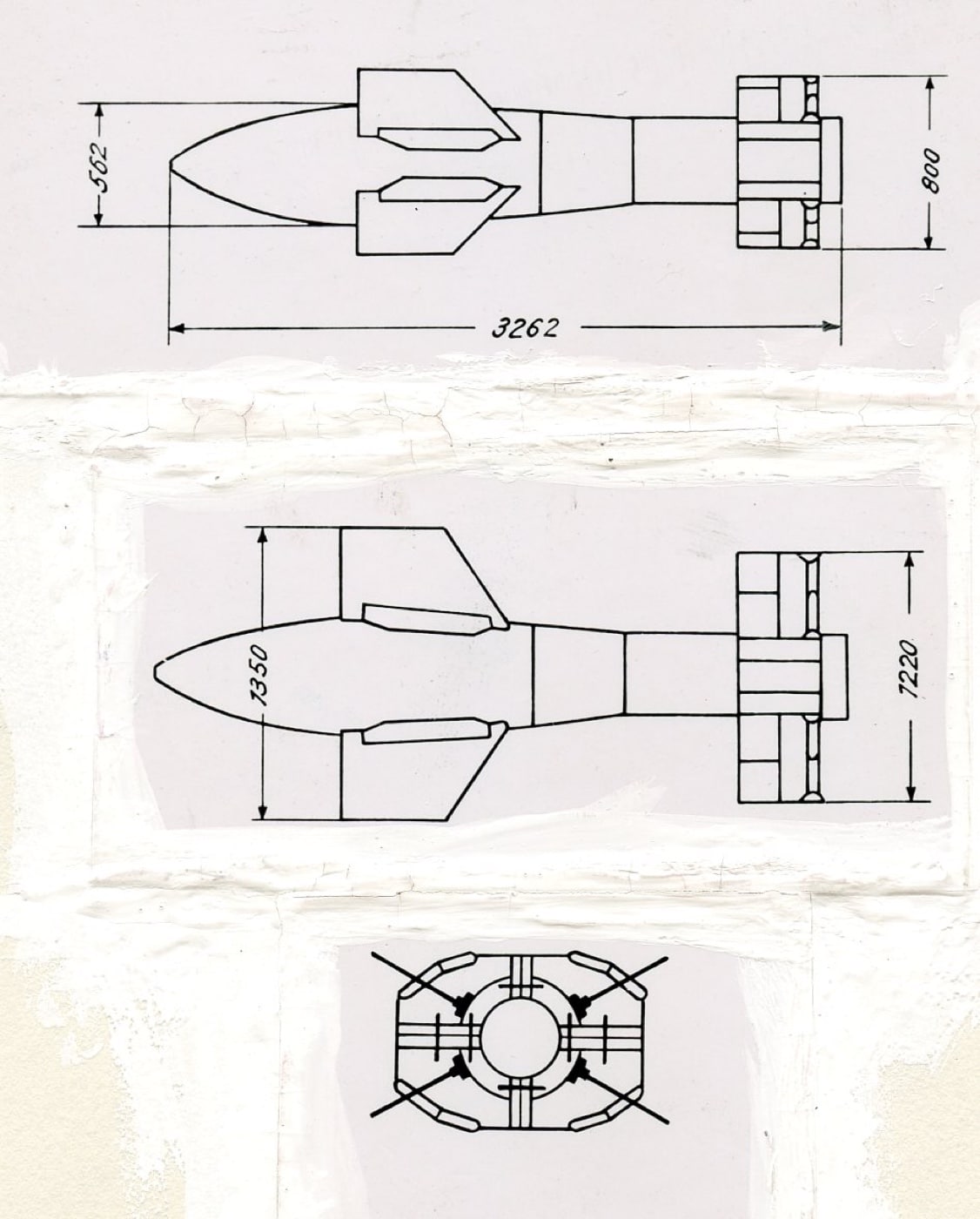

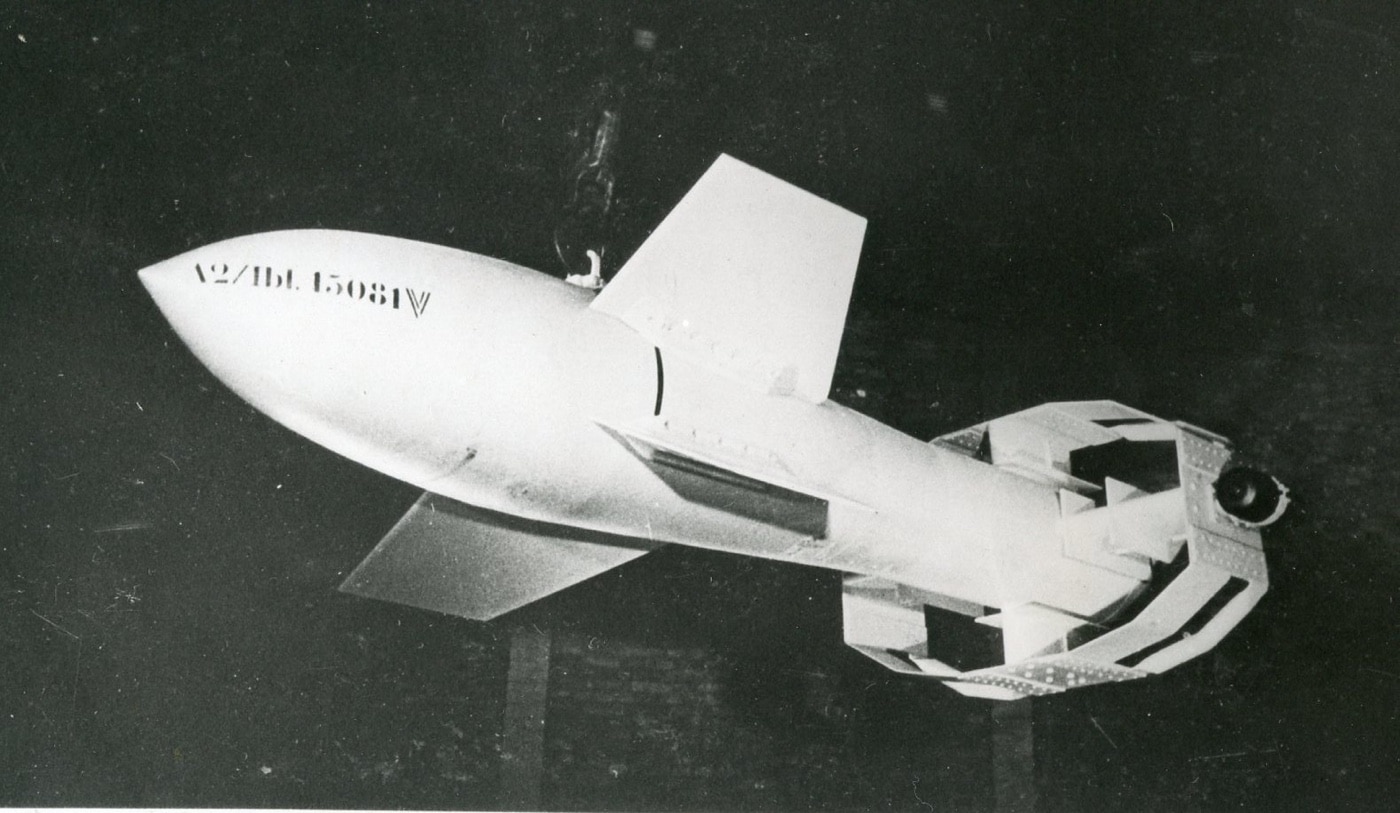

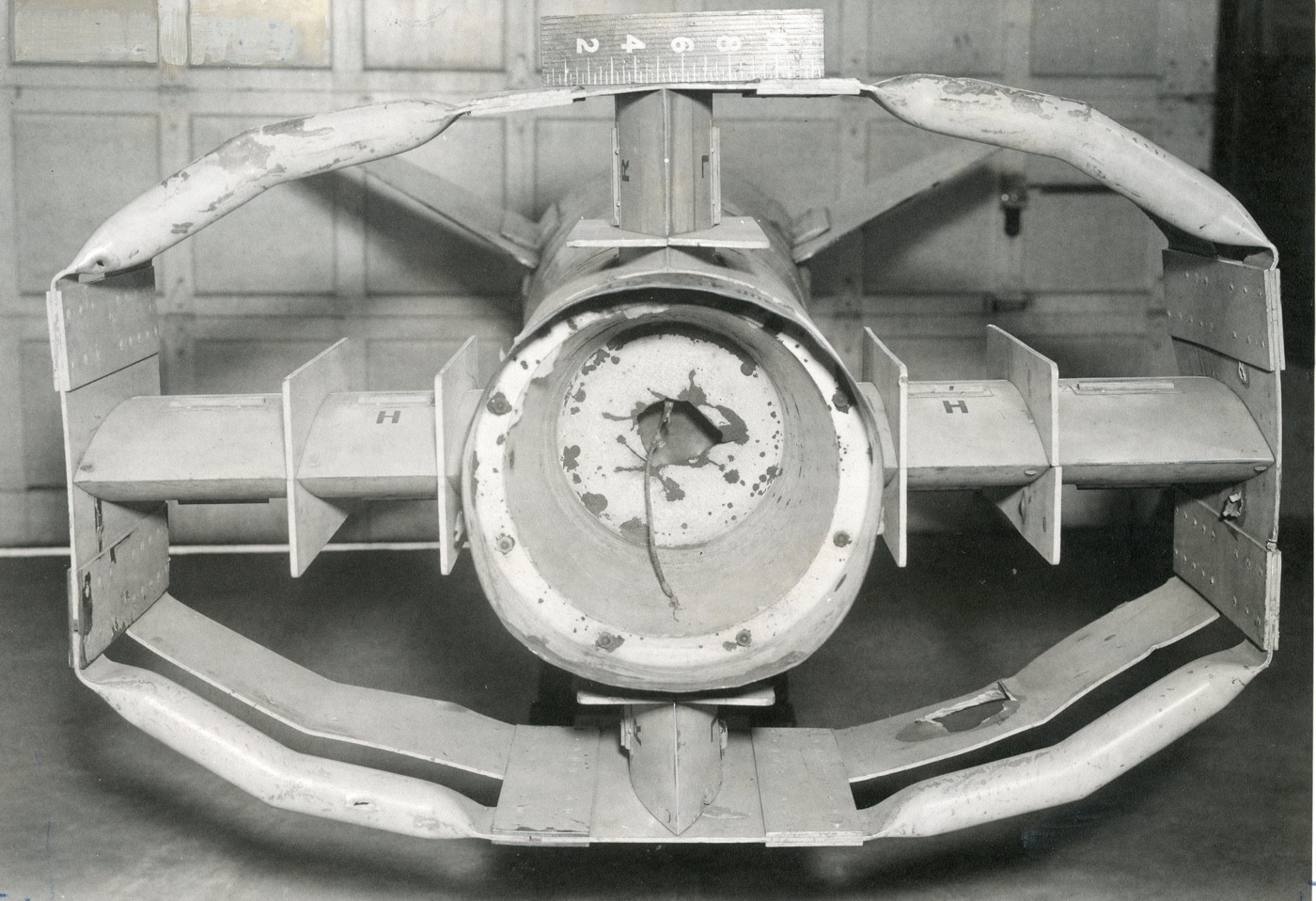

Bombing ships from high altitude normally produced negligible results, leading scientist Max Kramer and his team to develop the Ruhrstahl SD 1400X or “Fritz X” radio-controlled glide bomb. The term “glide bomb” seems rather gentle, but in reality, the Fritz X was a 3,000-pound weapon (with a 710-pound warhead) propelled by gravity alone, achieving a speed of 767 miles per hour.

Fritz X was radio-controlled (Kehl-Strasbourg radio control) with movable spoilers in the tail and featured a massive flare in the tail that helped the operator track and guide the bomb to the target. However, it was a delicate operation for the controller, due to the “parallax problem” — as it was difficult to triangulate the impact point between a quickly moving bomb, a quickly moving launch aircraft and a moving ship.

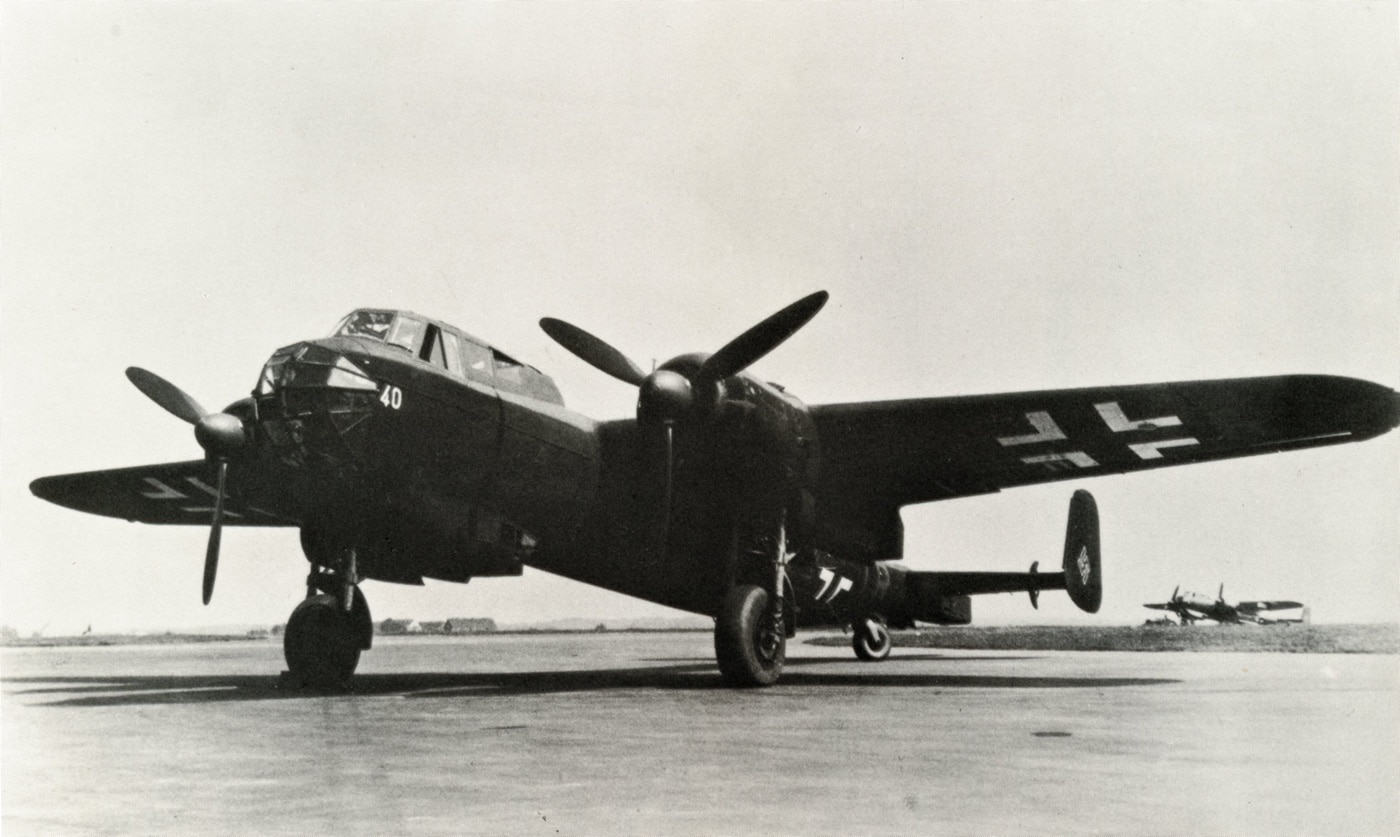

The first launch aircraft for Fritz X was the twin-engine Dornier Do 217 bomber. The Do 217 featured a large, glazed nose with excellent vision for the controller, and the aircraft had decent performance at high altitude — allowing the Dornier to carry a pair of Fritz X bombs to above 20,000 feet.

The preferred altitude for launch was 18,000 feet, with about a three-mile distance to the target. The launch aircraft had to maintain its course as Fritz X fell, and the pilot could not take evasive maneuvers to avoid flak or interceptors. Even so, hopes were high as units training with the Fritz X achieved a nearly 50% hit rate during tests with the new bomb.

On September 7, 1943, a squadron of Dornier Do 217 bombers of the Luftwaffe’s KG 100 was sent to Istres to reinforce German anti-shipping units preparing to combat the Allied armada gathering around Salerno. As Italy surrendered to the Allies, the Italian Fleet, with three modern battleships, six cruisers, and 13 destroyers, was to sail to Malta to surrender.

The Germans considered the Italian surrender a “stab in the back”, and, from a military perspective, could not allow the Allies to gain control of the Italian fleet. With that in mind, on September 9th, nine Dornier bombers took off from Istres to intercept the Italians when the fleet reached the straits of Bonifacio. Neither the Italians nor the Allies were aware of the Fritz X, but they would soon become familiar. The Germans launched a total of nine Fritz X bombs from approximately 19,000 feet.

The German bombers had trailed the Italians for a short time, but the ships did not alter their course or take evasive action. It is thought that Admiral Bergimini (in overall command of the fleet aboard the Roma) believed that the planes were a promised Allied escort. Regardless, positive identification of the bombers would not have been possible at that range and altitude.

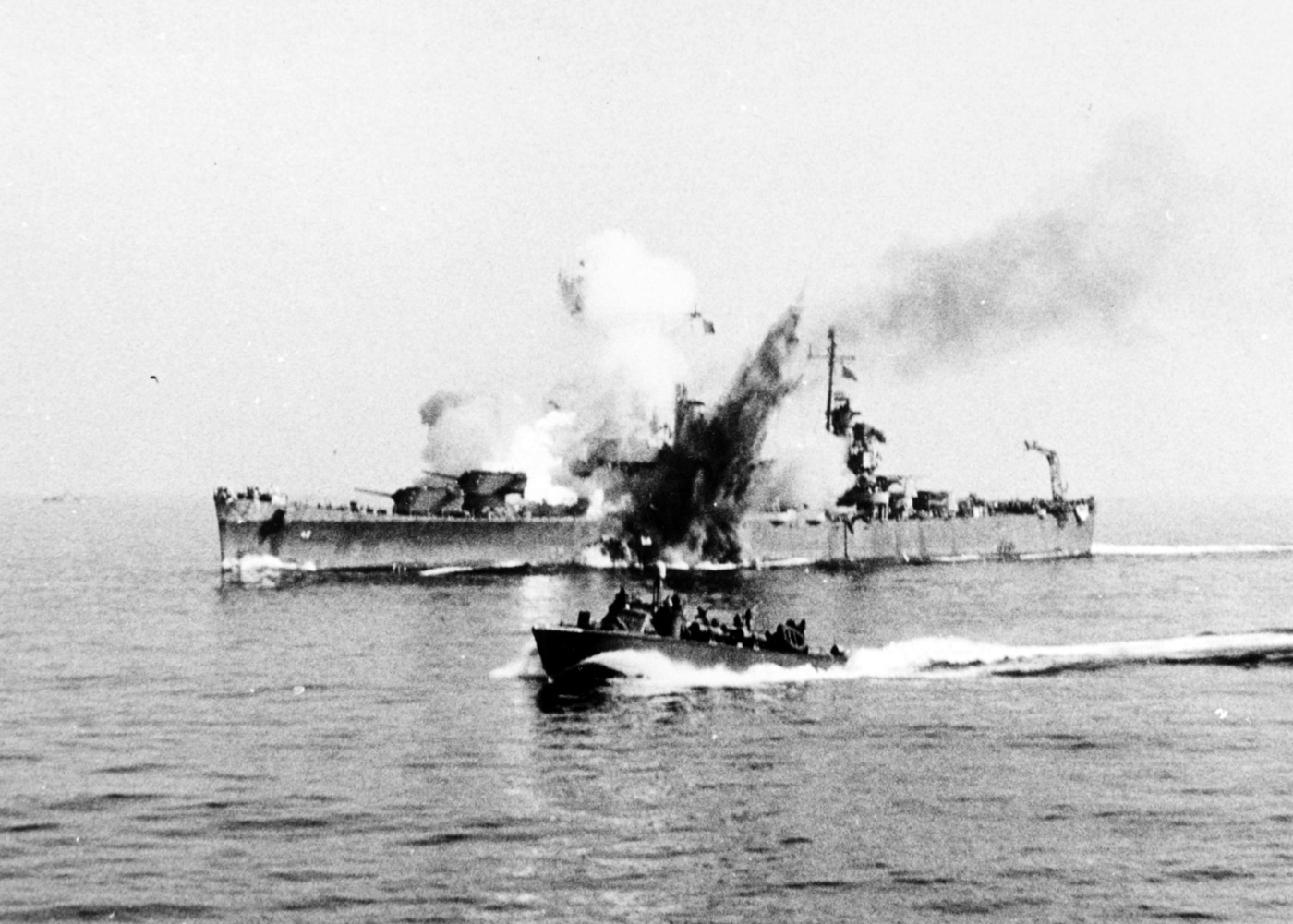

The first Fritz X hit the Roma on the stern, instantly flooding boiler rooms, the aft engine room, starting fires in the rear of the ship. Roma was limping on reduced power when the second Fritz X pierced the deck armor near the number two turret and detonated in the forward engine room. The explosion caused terrific flooding and worse — it detonated the ammunition in the number two turret’s magazine. The resulting blast broke the giant ship in two, and Roma capsized and sank in minutes, taking nearly 1,400 crewmen, along with Admiral Bergamini, to their deaths.

Fritz was not finished. As the Italian fleet began evasive maneuvers, the battleship Italia (formerly Littorio, and sister ship to Roma) was targeted and hit just ahead of her number one turret. The bomb penetrated the 6.4 inches of armored deck, then passed all the way through the ship, exploding below the hull. This caused massive damage to the Italia’s bow, with flooding, and multiple casualties. Italia was essentially out of commission, but she was able to sail to Malta, where she was interned. Italia and Vittorio Veneto were eventually sent to the Great Bitter Lake in the Suez Canal, where they were kept until October 1946.

Fritz X had arrived out of the blue and eliminated two-thirds of the Italian battleship force in just a few deadly moments.

Attacking the Invasion Fleet off Salerno

The Luftwaffe then turned its attention to the Allied invasion fleet near Salerno, and the first Fritz X attacks came on September 11th. The anchorages were crowded with ships of all types and there was no room for evasive maneuvers.

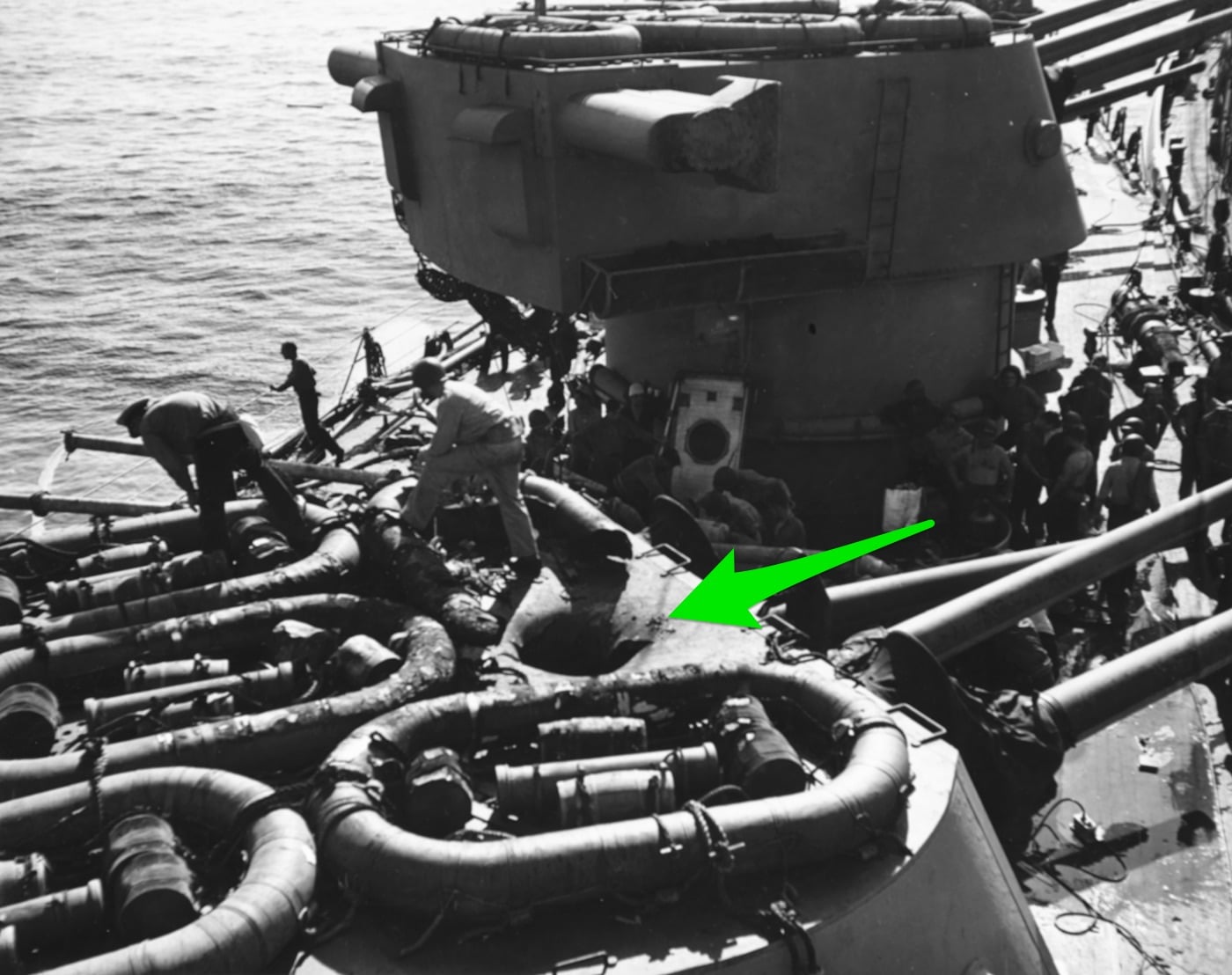

First, the Brooklyn-class light cruiser USS Philadelphia (CL-41) was damaged by a near miss. Then, its sister ship, the USS Savannah(CL-42,) came under attack and a Fritz X penetrated Savannah‘s port side near C turret. Excerpts from the USS Savannah’s war diary describe the damage, and the confusion related to the attacks by a new weapon:

“Men aboard the Savannah saw the bomb leave the plane. Many of them thought, in the first second or two of its downward course, that it was not a bomb but one of the fighters that had fallen victim to the German’s guns. This, they explained, was because the missile trailed a plume of smoke like that of a crippled plane.

But it was a bomb, and it had Savannah’s name on it, for it struck with the force of several thousand pounds of screaming metal traveling at four or five hundred miles per hour on the number three turret, the third from the bow and immediately in front of the bridge.

In the hundredths of a second from the time it thundered through the turret’s protective armor until its time fuse detonated its huge cargo of high explosive, it plunged down the turret’s barbette and on into the depths of the ship below the waterline. There, in a part of the vessel surrounded by magazines and oil tanks, it burst like the clap of doom.

From a hole 20 feet in diameter in her bottom, and a narrow rip 60 feet long in her side below the waterline, the sea poured into the Savannah. Water-tight doors had been torn off by the blast, while decks and bulkheads near the explosion were ruptured.”

From a crew of nearly 1,400, the Savannah lost 197 men and 9 officers killed.

“Commander Philip D. Lohmann, now Acting Captain of the ship since Captain Cary’s transfer to other duty, said the hit might have been scored by “good precision bombing done with a good bomb sight”, despite the evidence of those who saw the bomb “twist”. But two pieces of evidence point to radio-direction of the huge charge. First, fragments of the bomb itself: these included certain coils and other bits indicating the presence of electric circuits in the bomb. Second, the plume of smoke trailing the missile as it plunged may have been a device by which the bombardier could follow its course by eye and thus direct it by radio.

What has been determined about the bomb is, of course, a military secret, but at the time it struck the Savannah, bombs of similar characteristics had been encountered only a few times previously and few facts were known.

Command Lohmann said a bomb which appeared to be of the same type, missed the cruiser Philadelphia by the narrowest of margins only a short time before the Savannah.”

Guided Bomb Damage Mounts

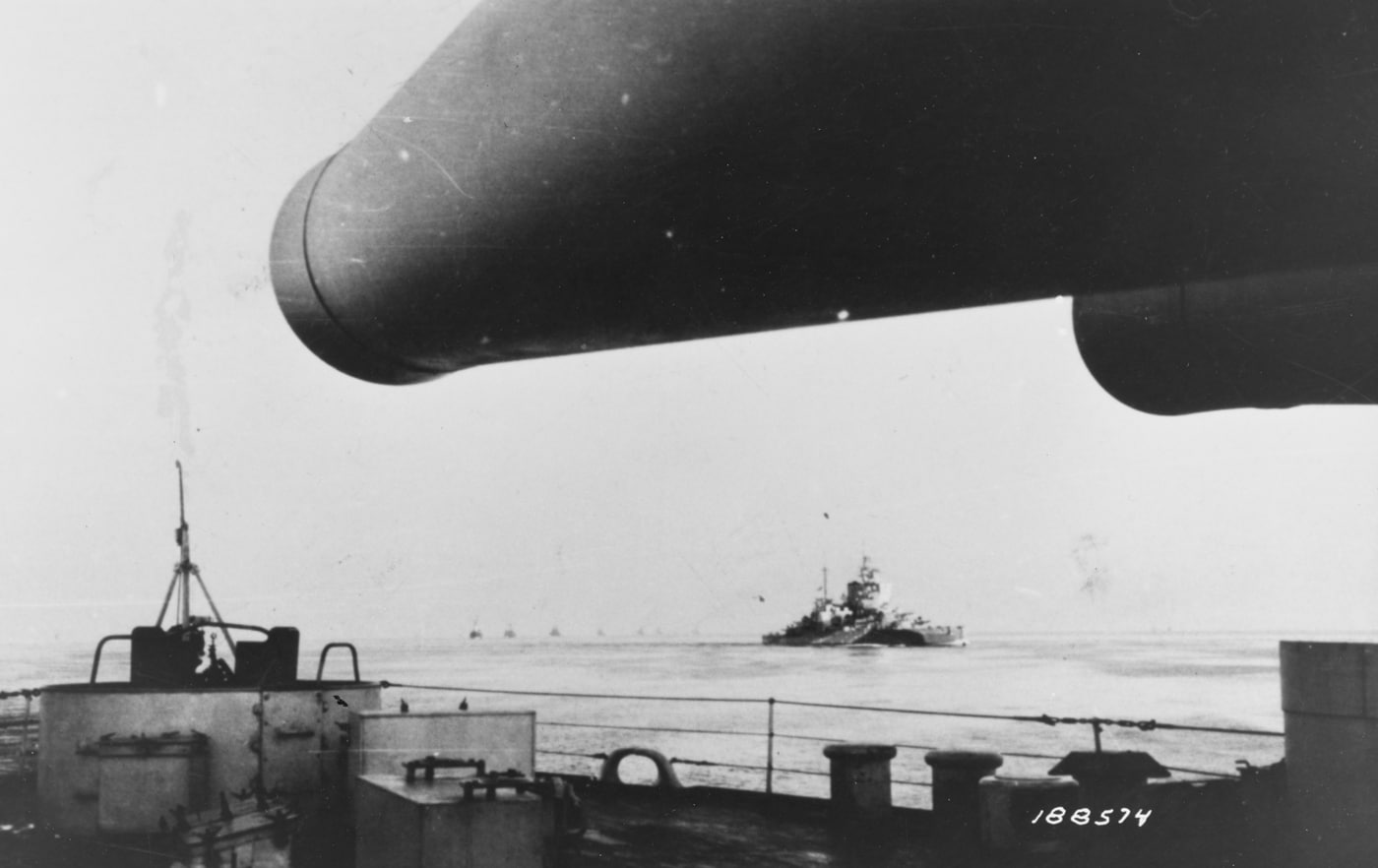

Soon after the hit on Savannah, the British cruiser Uganda was struck and badly damaged. On September 14th, more Dornier 217’s approached the invasion fleet; embarrassingly, they arrived undetected.

While the British battleship HMS Warspite was bombarding the invasion beaches, she was hit by a Fritz X near her funnel, and the bomb crashed through her decks to blast open a 20-foot hole in the bottom of the hull.

Warspite was out of action for many months, but she recovered to become the first Allied ship to open fire during the D-Day shore bombardment on June 6, 1944.

U.S. Navy Bulletin Regarding Countermeasures Against the Fritz X

The following is a U.S. Navy bulletin issued about the Fritz X.

ALL CONVOYS WHOSE DESTINATION IS EUROPEAN OR NORTH AFRICAN PORTS

Description of one type of enemy bomb and recommended evasive action:

Description: In addition to the glider bomb (HS-293), the German air force is now using another type guided missile called the “High Angle Bomb (Fritz-X)”. The following description is based on the best information available and may be modified as more about these missiles becomes known.

The High Angle Bomb (Fritz-X): This is a normal 3000-pound German bomb with a special tail assembly containing a radio receiver. Four fins occupy about one-third of the length behind the nose, with a normal brake ring on the tail. The bomb is dropped from high altitude by Dornier 217 aircraft by means of normal bomb sight. The plane is pulled up sharply to enable the bombardier to keep the bomb in sight. As the bomb nears the target he can, by radio transmission, control flaps in the tail of the bomb sending it to the left or right or into a steeper dive. The bomb is characterized by a smoke or colored vapor trail to aid the bombardier to follow its fall.

Counter measures: Counter measures for this bomb are the same as those employed against the glider bomb. If attacked during darkness or twilight by the HS-293 or the Fritz-X, the use of colored very stars may serve to confuse the enemy if fired in the direction of the missile which carries a light in the tail.

A Rapid Decline

As suddenly and dramatically as Fritz X appeared, its introduction was followed by a rapid decline. As the Allies pushed northwards into Italy, more airbases became available and Allied fighters were able to cover the landing fleet. Also, the Germans began to focus their attention on Mediterranean convoys, and strangely, the Fritz X was considered too powerful for use against lightly armored ships like merchantmen or destroyers.

As many Fritz X hits on well-armored warships saw the bomb pass all the way through the target, the Germans opted to use the Henschel Hs 293 glide bomb, with a 650-pound warhead that was designed for blast effect and not armor penetration.

The Allies also began to deploy electronic countermeasures to interfere with the FuG 203/230 radio system used by Fritz X (and the Hs 293). The British Type 650 transmitter proved particularly successful in this role, and after the Anzio landings in January 1944, the effectiveness of the German glide bombs was greatly diminished.

Few Fritz X bombs were used in attacks against the massive invasion fleet off Normandy, and German bombers were generally kept at bay by a combination of Allied air superiority, anti-aircraft fire and inexperienced crews. In the last weeks of the war, some Fritz X bombs are suspected to have been launched against bridges on the Oder River, without result.

Advanced Ship-Strike Technology

Fritz X’s entry into combat represented a sudden and dramatic challenge to Allied warships. For a brief and terrifying period, it seemed that no ship was safe. The danger was averted with a combination of air cover and eventually electronic countermeasures.

Even so, the story of the Fritz X foreshadowed other anti-ship weapons’ successes in the future, like the French Exocet missile used by the Argentines during the Falklands War in 1982, and the Ukrainian Neptune missile that sank the Russian cruiser Moskva in April 2022.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

103

103