Germany’s Desperate Battle to Stop Allied Bombing

June 18th, 2024

8 minute read

As U.S. bomber formations appeared over Occupied Europe with increasing regularity during 1943, Luftwaffe interceptors were obliged to find ways to stop them.

Luftwaffe fighters had experienced considerable success earlier in the war against British twin-engine bombers flying unescorted missions at medium altitudes. The weapons of the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Bf 110, along with the newer Focke-Wulf Fw 190, were strong enough to bring down the RAF bombers in their short period of daylight raids. Consequently, British bombers switched to night raids.

Enter the American Flying Fortresses

To their disappointment, the Germans soon found that fighting the American B-17 Flying Fortress proved a much greater challenge. Adolf Galland, the Luftwaffe’s General of Fighters, said that the B-17 “has every possible advantage combined in one bomber…heavy armor, enormous altitude, tremendous defensive armament, and great speed.”

As the 8th Air Force grew, so did the size of the B-17 formations sent to bomb the Third Reich. German interceptors watched the B-17 “flying porcupine” grow into massed squadrons of prickly beasts, protected by seemingly impossible numbers of of .50-caliber machine guns covering the standard attack routes.

In early and mid-1943, the Browning AN/M2 defensive guns held a range advantage over the German interceptors — who normally used tracers from their 7.92mm MG 17s to sight their 20mm MGFF and 20mm MG 151 cannons. This brought them within killing range of the B-17s guns, and the hellstorm of tracers coming at them caused many German pilots to open fire from too great a range, and to break off their attack much too soon.

A Matter of Numbers

Inspection of downed B-17s showed that, when attacked from the rear, it took an average of twenty hits from 20mm cannons to bring down a Flying Fortress. Unfortunately for the Germans, the average Luftwaffe fighter pilot was only hitting the bombers with about 2% of his shots in stern attacks from normal ranges.

In that equation, most of the Luftwaffe’s single-engine fighters couldn’t carry enough 20mm ammunition to bring down a B-17 by themselves. The Luftwaffe’s weapons and tactics needed to be changed.

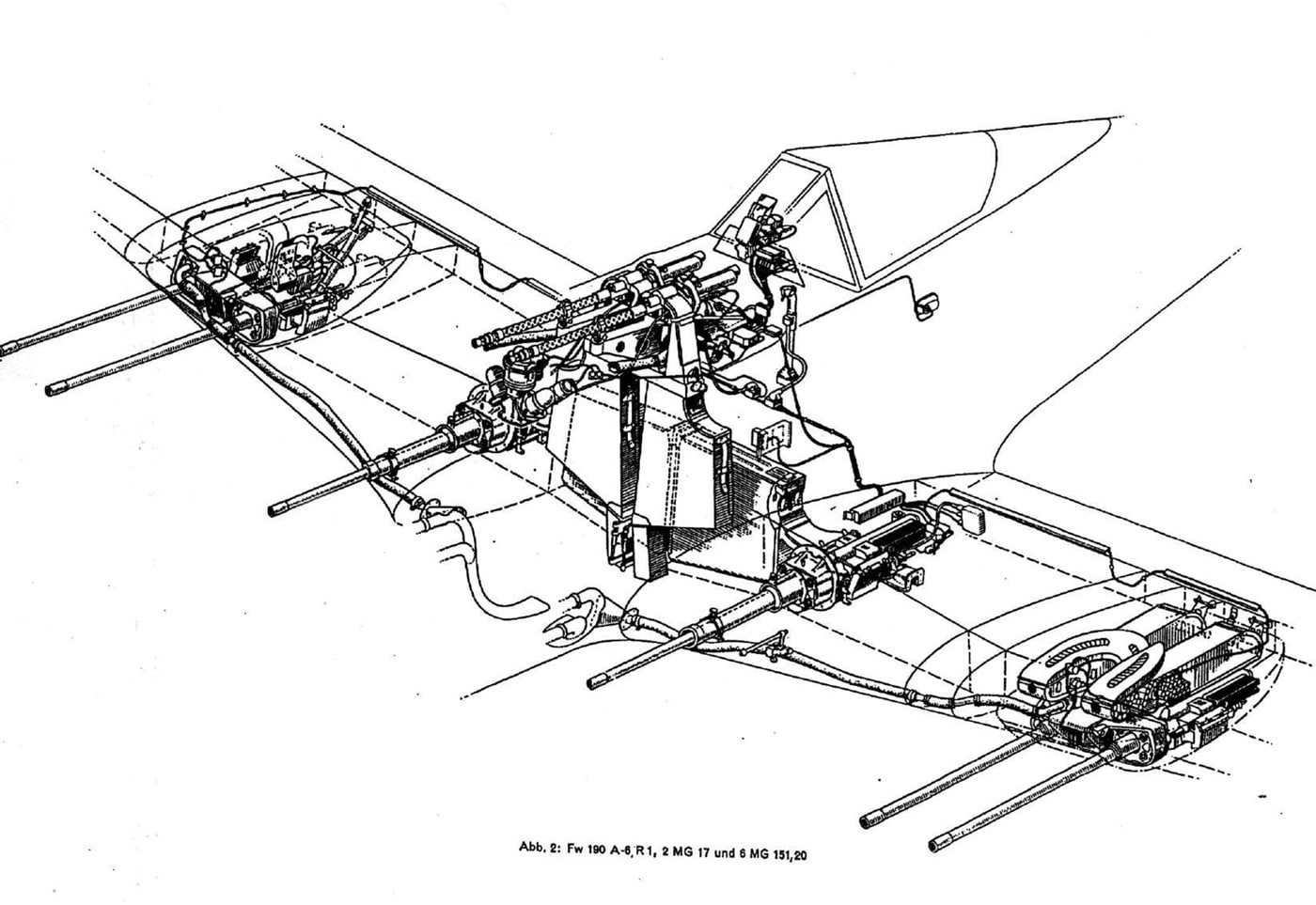

The first improvements in armament saw the MG 17s replaced by 13mm MG 131s, and the slow-firing and short-range MGFF cannons were superseded by the more powerful MG 151 weapons.

These changes were helpful, but on their own they were not enough. When the fighters began to attack the B-17s from the front, that is when the Flying Fortresses began to fall in concerning amounts. The head-on attack meant that the interceptor would face the least number of defensive guns, and the incredible closing speeds (at times more than 500 mph) meant there was little time for the gunners to get off a well-aimed burst.

Likewise, the German pilot had little time to shoot, but his target was substantially larger, and the impact point of his fire was often the engines or the cockpit. These hits could be fatal for the bombers.

While the 8th Air Force’s unescorted missions pressed deeper into the Reich, the Germans went to great lengths to find air-to-air weapons that would either keep their interceptors outside the range of the American’s .50-caliber machine guns, or provide more destructive force when they hit.

The following are some of the Luftwaffe’s specialized anti-bomber weapons.

Stovepipe W.Gr.21 Rocket

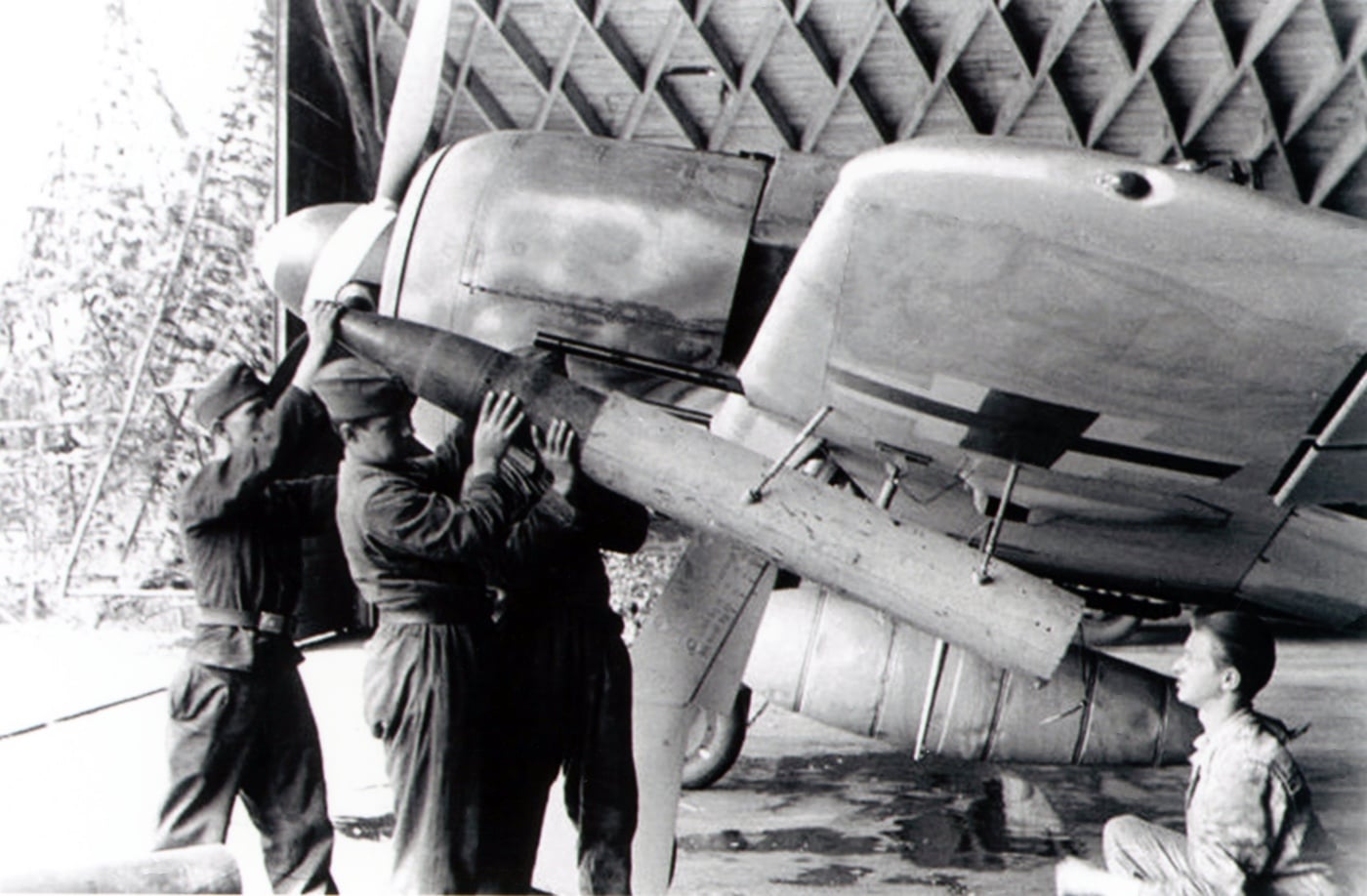

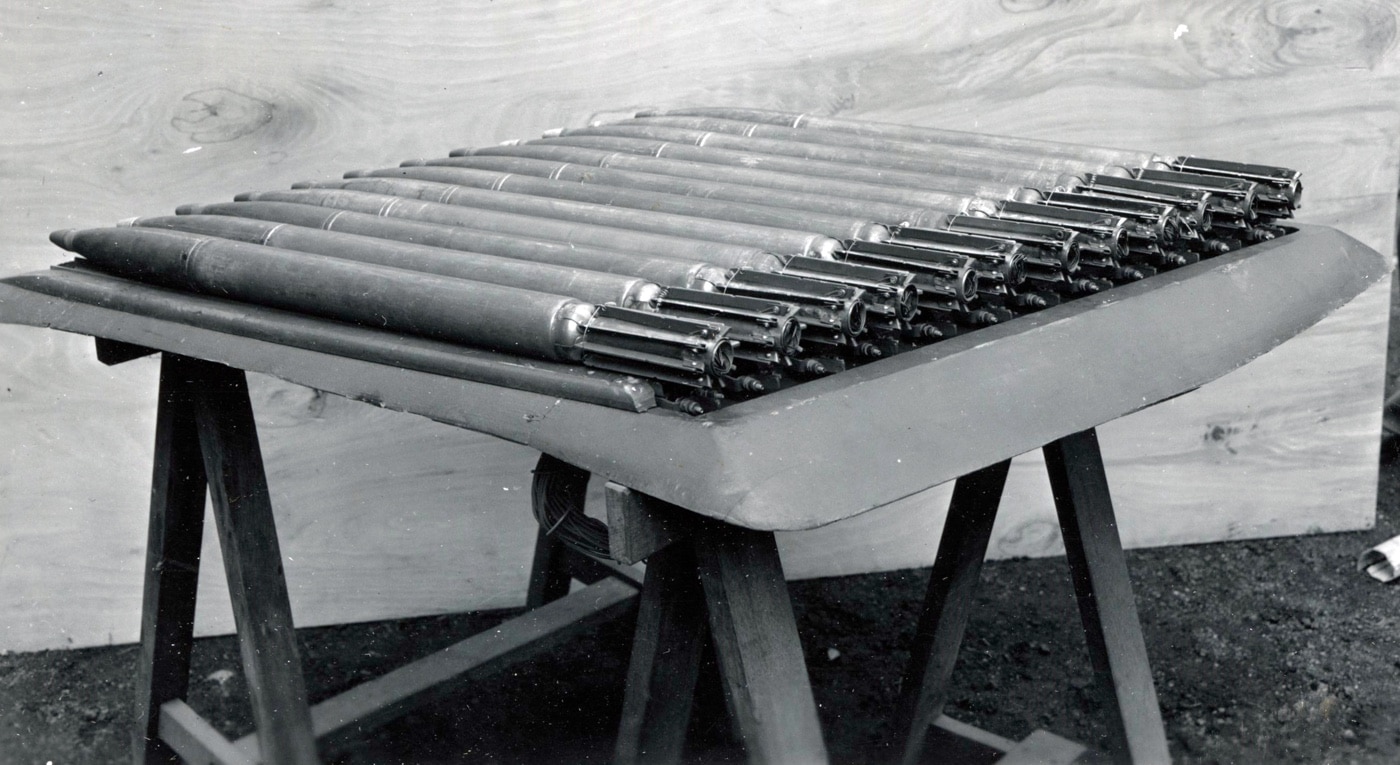

Looking for a way to break up the bomber formations, the Germans adapted their 21cm Nebelwerfer 42 artillery rocket for use aboard Luftwaffe interceptors. Called the Werfer-Granate 21 rocket launcher, or W. Gr. 21, these were referred to as the BR 21 in much of the German literature from the time.

It was a relatively simple conversion, using a short tube mounted beneath the wings — single tubes on Bf 109s and Fw 190s, and twin tubes under the wings of twin-engine heavy fighters Bf 110s and Me 410s.

The mortars were sighted by Revi 16B reflector sight fired simultaneously by a separate button on the control column. The low-velocity rockets were spin-stabilized, but they were anything but accurate, and since they drooped in flight, they needed to be sighted at least 60 meters above the target.

The use of the rockets was truly a crapshoot because the weapon’s time fuse was pre-set and could not be adjusted — the pilot’s estimating as best they could with a weapon of inconsistent performance.

Germans called the rocket tubes “stovepipes” as they seriously degraded the fighters’ flight performance, in both speed and altitude. Understandably, they were not popular among the crews.

However, in the autumn of 1943, the 8th Air Force considered the rockets a major threat. Aside from the rare direct hit, the biggest successes of the W.Gr. 21 rockets came when their blast effect broke up a bomber box, leaving the individual B-17s to be hunted down by fighters.

Pneumatic Hammer — 30mm MK 108

Faced with the challenge of knocking down massive four-engine bombers like the B-17 and B-24 (as well as the British Lancaster and Halifax), the Luftwaffe turned to larger-caliber weapons that offered more powerful ammunition coupled with a high rate of fire. This concept arrived in the summer of 1943 in the shape of 30mm MK 108 made by Rheinmetall-Borsig. The distinctive heavy thumping of the aerial cannon, cycling at 650 rpm, earned it the nickname of “the Pneumatic Hammer”.

German analysis showed that it took just four hits from the MK 108’s 330g ammunition to bring down a heavy bomber. The steel case ammunition used a “drawn steel” manufacturing process to create a mine shell featuring a thin but strong exterior, allowing a much larger explosive charge to be used in the warhead.

The MK 108 was relatively light and could be fitted beneath the wings of single-engine fighters. Its range was short, and with a relatively low muzzle velocity (1,770 fps), pilots had to close in to make the most of the firepower.

In 1944, the Luftwaffe began to use specialized Sturmjäger squadrons, flying heavily armed and armored Fw 190s. These pilots specialized in close-range attacks from the rear — opening fire at less than 400 meters with 20mm MG 151 cannons and targeting the tail gunner. At 200 meters, the 30mm MK 108s would be fired on the inboard engines and the wing root.

Some gunfights in the sky were at point-blank range, as the Sturmjäger continued firing as close as 50 meters, while the B-17 gunners took a heavy toll on the attackers.

The Big Gun: 50mm BK-5

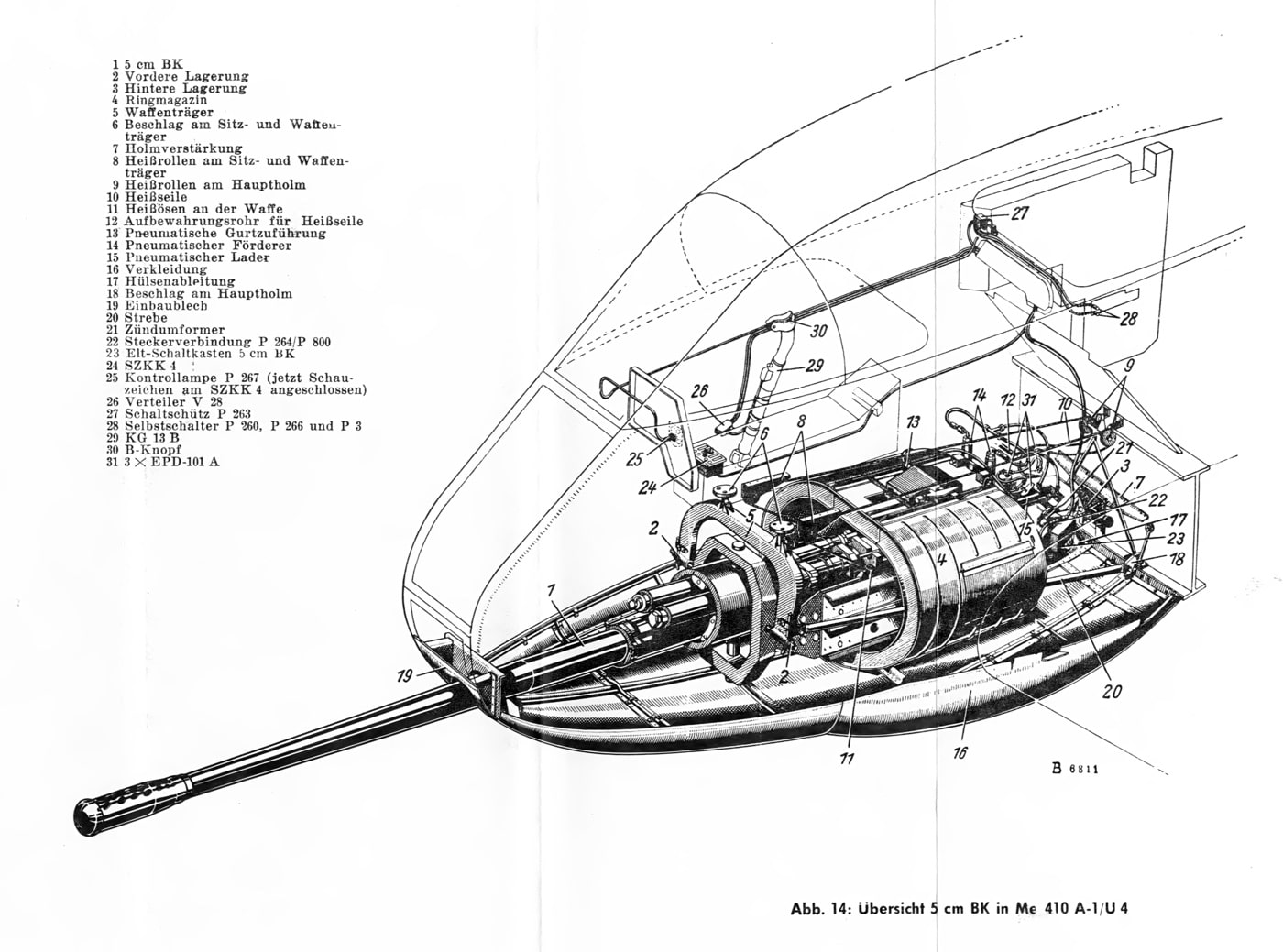

Hoping to stay far outside the range of the Browning .50-caliber MGs, the Luftwaffe turned to a particularly heavy aircraft weapon. The 50mm Rheinmetall Bordkanone 5 (BK-5) was an adaptation of the 5 cm KwK 39 tank gun — and at nearly 10 feet long and weighing almost 1,200 pounds, the BK-5 was one of the largest aircraft weapons of all time.

The Messerschmitt Me 410 (Me 410 A-1/U4) was selected to carry the BK-5, and the cannon protrudes rather awkwardly from the lower part of the nose. The BK-5 could be used with the fighter’s standard Revi gunsight, and it was also provided with a special telescopic sight for long-range shooting. Rocking and buffeting at altitude made effective use of the telescopic sight hopeless — and the whole notion of picking off bombers from a distance quickly evaporated when combat operations started.

The BK-5 handbook provides a very optimistic estimate of 900 meters as an effective range. In combat, the practical range proved to be 500 meters, and the destructive power of the BK-5’s ammunition (with only 21 rounds magazine capacity) left much to be desired. Impressive though the big gun may have looked, successes for the BK-5 armed Me 410s were few. Its impact on flight performance was considerable, and the Me 410 had little chance to escape if escort fighters were nearby.

Germany’s Own “Divine Wind”

Despite all the technological advances and the increasingly heavy armament they carried, Luftwaffe interceptors had one consistent solution to destroy heavy bombers: get in close and shoot accurately.

The danger from the bomber gunners’ .50-caliber machine guns was a constant, unflinching threat. In the last desperate days of the Reich, the 8th Air Force recorded:

Signs of desperation are evidenced by the fact that Fw 190 pilots deliberately rammed the bombers, baling out before their planes went into the bomber formations and making fanatical attacks through a murderous hail of fire.

Tactics were thrown to the wind and attacks were made from all positions, mainly in ones and twos…it appears that although the enemy is fighting a losing battle, the German Air Force is preparing to fight to a finish in a fanatical and suicidal manner.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

437

437