Hanging Fire: Top 5 Failed Ammo Tech

July 8th, 2021

6 minute read

Where there’s a will, there’s a way. This has been one of the main mantras in the world of firearms ammunition. Round lead balls fired from smoothbore muskets gave way to bullets featuring hollow bases that would expand out when fired to engage the rifling of the barrel, and by extension improving accuracy.

Self-contained metallic cartridges were a total game-changer by keeping powder dry and incorporating the primer into one unit. This prevented inclement weather from preventing them from firing and also freed up some of the extra components that used to need to be carried by shooters. Magazines that stacked cartridges vertically rather than horizontally such as in a tubular magazine made it safe to fire pointed bullets.

But, for every step forward, there can be two steps back. For every success, there was a failure. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see today that some of these were never going to work; but at the time of their invention, success was anyone’s guess, and the only way to know for sure was to give it a try. Here are five top examples covering the last century and half.

Rocket Ball

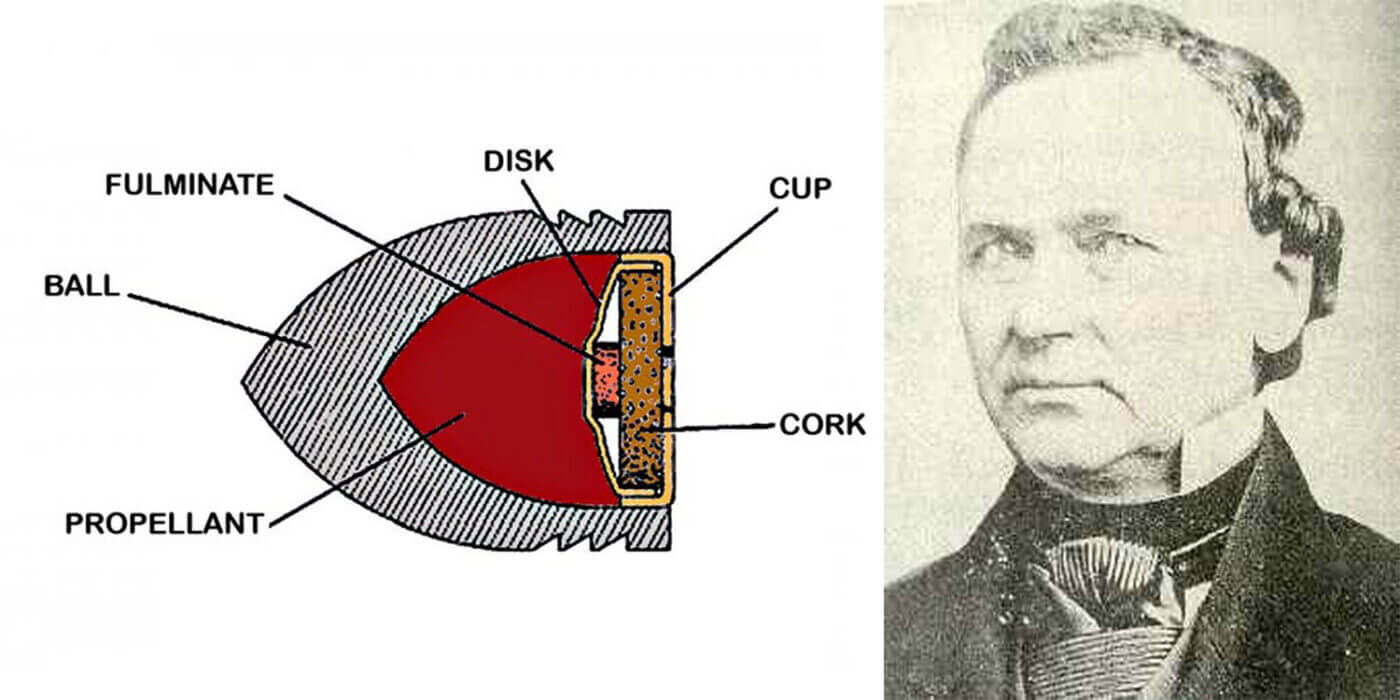

Walter Hunt was a mid-19th century New York-based inventor who created many things we today would know, such as the fountain pen as well as the safety pin, and much more. He also took a shot of improving ammunition design with a unique design known as the “Rocket Ball.” It however would not match the success of his other creations.

Acquiring a patent in 1848, the Rocket Ball was designed to negate the need for a paper cartridge, which was the current best technology at that time. In a sense, Hunt had created a caseless round.

Designed in .31 and .41 calibers, the Rocket Ball rounds featured charges of gunpowder packed into hollow bases of the bullets. The cavity was filled with powder and then covered with a waterproof cap. This cap had a small hole in it to allow the ignition source access to the powder. In addition, this hollow base expanded when fired to engage the rifling, improving accuracy.

While exceedingly clever, this design lacked power due to the lack of area for a significant powder charge. Even in the slightly larger .41 caliber rounds, it still wasn’t much. As result, this round quickly faded into obscurity.

Dardick Tround

In the mid-20th century — specifically, 1958 — David Dardick was granted a patent for a unique magazine-fed revolver. Yes, that’s right; a magazine-fed revolver. His gun used U-shaped chambers that were not completely enclosed instead of more traditional round chambers. This was the key part of the design that would allow the rounds to feed automatically into the chamber from the magazine. Extraction was also automatic.

Unfortunately, the U-shaped rounds had to be fed in a very specific fashion or the firearm would not function. He had to go back to the drawing board and do some redesigning. That same year, he was issued another patent for a triangular-shaped round. This design ensured the rounds feed more easily into the cylinder, ensuring greater reliability.

Dardick named these rounds “Trounds”, and the first gun for it was named the Model 1100. It was chambered for the proprietary .38 Dardick Tround. To ease ammo problems, a cylinder adapter was offered that allowed you to shoot traditional handgun ammo. Later versions had additional chamberings as well as carbine conversion kits. The handgun essentially fit into a frame with a longer barrel and a shoulder stock.

Unfortunately for Dardick, the public never embraced the design and the Tround and the guns remain merely a footnote in firearms history.

Gyrojet Rocket

By the early 1960s, Americans were enthralled with the space race and everything related to it. This included a wide variety of things, including the rocket fuel used to power our extraterrestrial endeavors.

MBAssociates, made up of Robert Mainhardt and Art Biehl, teamed up to develop small arms ammunition that employed solid rocket fuel as it’s propellant instead of the centuries old method of using gunpowder.

When the ammo design was finalized, the end result was a self-contained, non-reloadable brass cartridge that burned solid rocket fuel. The force from this fuel was channeled through jet ports at the rear of the cartridge that were angled to impart spin — much like traditional gun barrel rifling had done for more than one hundred years.

The gun’s hammer was actually located in front of the cartridge. It hit the nose, which pushed the round back onto the firing pin, and the rocket reset the hammer as it exited the barrel. The projectile would increase velocity as it headed down the bore, so barrel length had a notable impact — as did things like wind deflection at the muzzle. In theory, a longer barrel would help remedy this problem. Unfortunately, the carbine’s longer barrel didn’t fare much better.

By 1969, the company was in trouble. Their unconventional design, low muzzle velocity, questionable performance, inconsistent ignition, and expensive ammo (around $3 each) proved too much to overcome. They folded in 1969.

Two things have remained constant in the half century since production stopped. The rockets are still cost-prohibitive to own and shoot, and they’re still just as (if not more) prone to failed ignition now.

Daisy VL Caseless Ammo

Daisy, a household name in the air gun and BB gun world, wanted to expand their product line in the 1960’s and take things to the next level. The design that resulted was unlike anything seen before. It was devoid of a firing pin, extractor or ejector. Instead, Daisy leaned into their history and designed a gun that fired using a method the company knew all about: compressed air.

The rifle employed a tiny caseless .22 caliber lead projectile. The round had a nitrocellulose-based propellant that was molded, hardened, and affixed to the back of the bullet. The rounds were roughly the size of two pencil erasers stacked atop each other. They even looked similar to pencil erasers, albeit different in color.

Unfortunately, the propellant easily flaked off, rendering it unusable if this happened. If you were to dump a handful of these rounds in your pocket, the jostling motion in your pocket would loosen the nitrocellulose propellant from the lead projectile, leaving the shooter with a pocket full of ammunition that was completely unusable.

Despite developing a specially design ammunition package to protect the rounds, there were bigger problems afoot. Since the round used a combustible propellant, the ATF deemed the rifle to be an actual firearm. Daisy was legally allowed to produce air guns, but not firearms because they did not possess a Federal Firearms License that would allow for firearms manufacturing. Production ceased in 1969.

EtronX Ignition

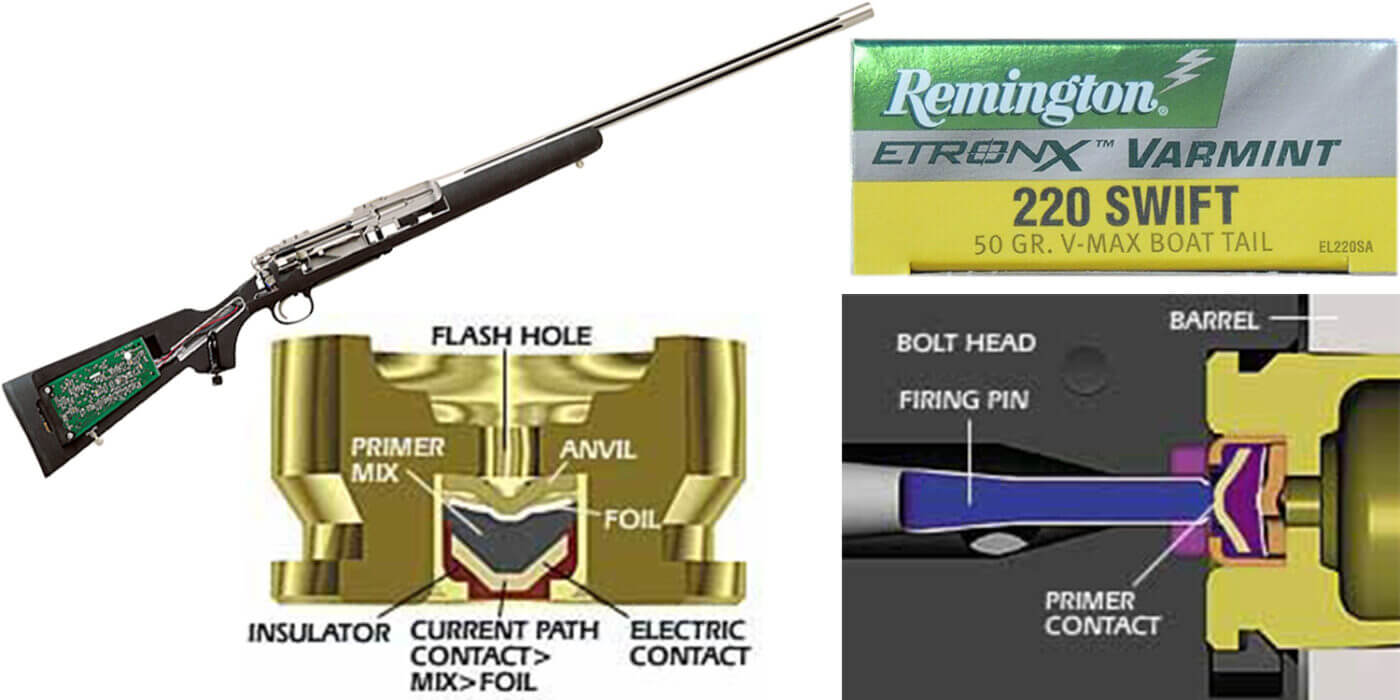

Sometimes, your efforts can be too ambitious. Case in point is the EtronX technology introduced in 2000 by Remington, which called it “the most significant advancement in rifle and ammunition performance since smokeless powder.” It was a lofty claim that was just as optimistic as everything else at the beginning of the new millennium.

Developed for the popular Model 700, the rifle’s bolt formed a crucial part in an electrical circuit between a special firing pin and primer when it was locked closed. When you pulled the trigger, a circuit was completed, sending an electrical pulse from the firing pin into the primer. This primer was specially designed to ignite by electrical impulse.

The result was a design with no moving parts other than the trigger, which reportedly had roughly a third less travel than a traditional one. The result was a near-instantaneous ignition of the round, resulting in theoretically a more accurate shot. The entire intricate electrical system was controlled by one nine-volt battery in the buttstock

The EtronX-equipped Model 700 rifles had an MSRP of $1,999, double the price of a standard Model 700. Despite its potential, the cost proved to be too much for the new design for most customers. Most people were hesitant to shell out the money to embrace this untested type of ignition system. The old adage of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” was in full swing here. As a result, Remington’s EtronX technology was gone within just a few years.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

200

200