A History of U.S. Recoilless Rifles: Applied Physics in War

September 5th, 2023

8 minute read

It’s highly unlikely Isaac Newton was thinking about warfare when he published his laws of motion in the Principia Mathematica back in 1687. As a brilliant and ground-breaking mathematician, Newton was pondering bigger things, but it wasn’t long before others saw battlefield possibilities in his theories.

Of particular interest to rudimentary weapons researchers was Newton’s 3rd Law of Motion that basically claims for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. And the age of recoilless weapons dawned.

What Is a Recoilless Rifle?

Flash forward three centuries and we see the modern recoilless rifle, a direct-fire weapon that effectively bridges the battlefield gap between rifles and mortars or artillery. Before we get knee-deep into this, it’s important to understand there is a distinction between a recoilless rifle and a recoilless gun. It doesn’t mean a whole lot in common soldier reference, but technically, only weapons that fire spin-stabilized projectiles from a rifled barrel are true recoilless rifles. Smoothbore variants, fin-stabilized or not, are recoilless guns or — more-commonly these days — rocket launchers. For the gunner, the principle remains the same.

The key here is that they all work basically by application of Newton’s third law of motion. The weapon is fired from a tube, and the launch of the projectile results in ejection of propellant gas at the rear, which counteracts most of the weapon’s recoil.

Basically, a big high-explosive projectile flies out the muzzle and a fan of hot gas simultaneously exits the breech end. What this equal and opposite force balance creates is a relatively lightweight weapon that can be man-packed and shoulder-fired or fired from a simple, mobile platform without having to worry about any kind or recoil-absorbing mechanism such as required on big mortars or artillery cannons. The gunner on the trigger or the mount system experiences little in the form of recoil. There is always some jolt, so no weapon is truly recoil-less, but more about that later.

Building Blocks — Early Designs

The earliest known example of a design for a gun based on recoilless principles was one created by Leonardo da Vinci in the 15th century. He designed a gun that was built to fire projectiles in opposite directions based on Newton’s pioneering principles.

Soldiers of the day weren’t overly excited about a weapon that was as likely to be as lethal to friendlies in the rear as it might be to enemies in front. So early pass on the recoilless principle for weapons of war. It was back to muskets, blades, bayonets and simple cannons for a couple of centuries.

World War I

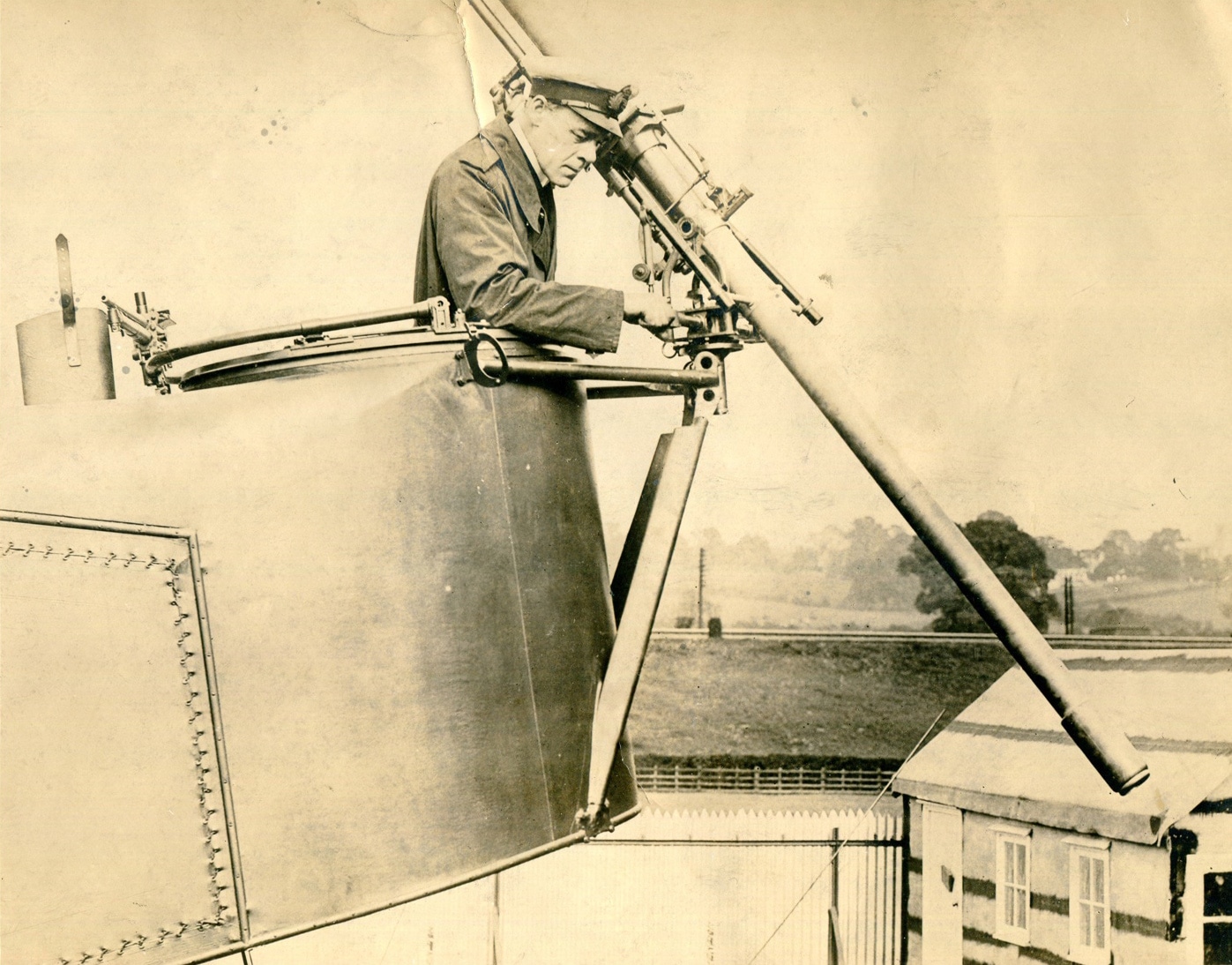

The first recoilless gun actually constructed and tested was a Navy model cobbled together just prior to WW I, Called the Davis Gun for its designer Commander Cleland Davis USN.

It was a variation on da Vinci’s concept with two tubes connected back-to-back. The backward facing tube was loaded with lead balls packed in grease, which was measured to match the weight of the explosive projectile being fired from the forward tube.

Not much traction with that one, but the Brits did tinker with it for use as an antisubmarine weapon mounted on patrol aircraft. Reports indicate not many RAF pilots volunteered to fly the thing, so the concept was shelved.

[Read all about this unique weapon in our article Davis Gun — Steampunk Airborne Artillery.]

World War II

Tinkering with recoilless weapons continued during early days of WWII by the Russians and the Germans in particular. The Germans had the most luck with the concept and eventually fielded a respectable recoilless gun, a 75mm smoothbore for airborne troops that could be para-dropped or airlifted into combat as an infantry support weapon.

The U.S. had seen the light at the end of the tube before America got involved in WWII combat. Recoilless rifles — as opposed to recoilless rocket launchers (technically recoilless guns) such as the M-1 and M1A1 bazooka — were fairly rare in American WWII combat formations.

[Catch the History of the Bazooka here.]

The most common recoilless rifle used by U.S. forces was the M-18, a shoulder-fired 57mm weapon that appeared in mid-war and was an anti-tank staple or bunker-buster along with a 75mm big brother that appeared late in the war. These two recoilless rifles remained in service right into the Korean War.

Cold War Goes Hot

By the time Korea got hot in 1950, the U.S. had basically replaced the 57mm rec rifle with the M-20 75mm version in all line outfits. It was a handy weapon that could be mounted and fired from the .30-caliber machinegun tripod, rigged to a jeep or anything else that could bear the weight of the weapon.

When more serious anti-tank firepower was needed against Soviet T-34s, the 3.5” rocket launcher, called the Super Bazooka at the time, was brought into the fight. For some arcane reason, the Bazooka was also designated M-20, but there was little danger of confusing a rocket with a recoilless rifle round, so the dual designation stood.

The Super Bazooka was so good in the AT role that the other M-20, the rec rifle, was mostly relegated to infantry support roles and did a notably effective job. But technically, the bazooka was a rocket launcher and we’re talking about recoilless rifles here.

The heyday of the true recoilless rifle had arrived and, by the end of the Korean fracas, the U.S. was all in on the concept and working overtime at weapons design. Naturally, they went big. The M-27 105mm rec rifle was fielded but proved too unreliable, too heavy and too hard to aim accurately.

Back to the drawing board which yielded the 90mm M-67, which served until U.S. designers solved the problems experienced with the larger weapon. Finally, the 106mm M-40 came into service in the late 1950s. That version of the most common recoilless rifle was actually 105mm, but the Ordnance Department designated it a 106 to avoid confusion with ammo for the M-27 that was still in their inventory.

American allied forces around the world inherited tons of WWII- and Korean War-vintage weapons, including plenty of 75mm and larger recoilless rifles. U.S. recoilless weapons were used in several worldwide post-war actions and a number of them fell into enemy hands as we discovered in Vietnam.

American forces in that war brought the 106mm recoilless rifles into combat effectively mounted on everything from tripods to jeeps and mechanical mules, to armored personnel carriers and even the venerable Ontos which carried six as the main battery on an armored and tracked vehicle.

[Learn more about this wild design in the article M50 Ontos — “The Thing” in Vietnam.]

Conclusion

This deep dive into the history and the physical science of recoilless weaponry led me to an understanding that Sir Isaac’s third law of motion is not absolute. It seems there are some elements of nature that bend the line a bit when force is exerted between two bodies. Friction, the nature of either body, or impulse, for instance, can cause an unequal reaction to what should be an equal and opposite action. It’s rare when forces are completely in balance. In the real world, recoilless rifles do recoil with varying degrees of severity, but it’s usually manageable and that’s the value added to the concept for soldiers on the battlefield.

All of this put me in mind of what Gunny Butts told me when I was learning to fire the 3.5” rocket launcher on a range at Camp Pendleton many years ago. “Remember this”, he growled. “Friendly fire isn’t, and recoilless weapons ain’t.” The black eye I got from snuggling up too close to the sight proved the latter point. Combat chaos with friendly and enemy rounds flying in every direction, taught me he was right about the former, too.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

96

96