Hotchkiss Mle 1914: Failure, or a Maxim Killer?

January 9th, 2024

9 minute read

At the start of the 20th century with the clouds of war on the horizon, while many of the nations of the world found it impossible to agree on many things, they still largely employed the same weapon — the Maxim gun. Invented by American-born Hiram Maxim, it was the first successful machine gun, and even today, firearms historians continue to debate which country adopted it first.

It is known that it was first employed in combat on October 25, 1893, at the Battle of Shangani, fought during the First Matabele War in what is modern-day Zimbabwe. By 1900, the Maxim gun had practically become synonymous with machine gun with most military planners.

Yet, there were still plenty of inventors who thought they could create something as good or perhaps even better.

In fact, numerous countries — including the UK and Germany — did improve upon the design, but one nation that had essentially dismissed the Maxim was France. There are several reasons why, but it almost certainly came down to the fact that in the 1890s a rivalry was still simmering between the UK and France over territorial aspirations in Africa — and it is even largely forgotten that a war almost broke out over the Sudan of all places. Cooler heads prevailed and within a decade, the UK and France were allies that would stand together in the Great War that was to come.

While the British employed the Vickers, an improved version of Maxim’s design, the French found favor with a competing design, the Hotchkiss. Yet, what is also notable is that both nations had Americans to thank.

Origins of the Hotchkiss Machine Gun

Like Hiram Maxim, Benjamin Berkeley Hotchkiss was an American who ventured to Europe and began producing firearms that he sold to the military. In the case of Hotchkiss, he had been a proven gun maker in his native Connecticut, and later went on to patent a line of projectiles for rifled artillery that were used by the Union forces in the American Civil War.

After the end of that horrible conflict, the United States government expressed little interest in new firearms, so Hotchkiss moved to France and set up a new arms company. Among the weapons he devised was the Hotchkiss gun, and a series of cannon revolvers that saw limited success.

After his death in 1885, Hotchkiss et Cie continued under the direction of another American, Laurence Benét. Seeing the success of the Maxim in the early 1890s, Benét sought to compete in the market — but was faced with difficulties because Maxim had secured patents on every possible method of recoil operation. However, in 1893, Austrian-born Captain Adolf von Odkolek offered a design for an air-cooled machine gun that operated completely differently from Maxim’s design.

Below the barrel was a cylinder in which ran a piston, while a small port/vent connected the gun barrel with the end of the cylinder so that when a bullet passed up the barrel, some of the expanding gas behind it was diverted through the port and into the cylinder to drive the pistol to the rear. In turn, it extracted the empty case and at the end of the stroke the spring expanded and pushed the bolt back — picking up a fresh round and chambering it.

It was the first true attempt to create a gas-actuated machine gun.

The design was rough but Benét saw that the concept was sound, and he perfected the design with the assistance of Henri Mercié. It should be noted too that Benét was a gun designer who was part John Browning and part Samuel Colt. In addition to being a bit of an inventor like Browning, he was a shrewd businessman like Colt, and purchased the design and patents from Odkolek’s design outright, refusing any royalty deal.

As a result, Odkolek lost out on what would have been a near fortune!

There is further irony that the soldiers of the Austrian Army were to find themselves on the receiving end of the Hotchkiss design.

Enter the Mle 1897

The French Army had established what can only be described as an uncomfortable working relationship with the Hotchkiss Company but adopted its machine gun in 1897, fittingly designated the Mle 1897. It proved to be only moderately reliable — its primary issue being that it was prone to overheating. As with Browning’s Model 1895 machine gun, the weapon was air-cooled rather than water-cooled like the Maxim design.

Firing long bursts with the Mle 1897 could quickly make the barrel red hot, despite the use of its massive brass cooling fins that were meant to act as a radiator. Benét attempted to address the issue in the subsequent Mle 1900, which employed steel cooling fins. It was effective, but not “good enough” for the French Army, which never accepted that perfect was the enemy of good.

The French Military Takes Over

Whereas the British Army was happy to allow the Vickers Company to refine the Maxim gun, the French Army opted to take matters into its own hands — having never been fully satisfied that a private firm was producing its weapons.

The first attempt to improve upon the Hotchkiss Mle 1897/1900 was the “Puteaux,” which was developed in 1905. It was little more than the former weapon with additional fins on the barrel and a complicated device added to vary the rate of fire. It was heavy, unreliable and did little to address the overheating issues. The Puteaux was eventually relegated to use in France’s frontier forts.

In 1907, the French Army introduced the St. Étienne Mle 1907, and it has been described as a Hotchkiss with everything changed for the sake of changing it — largely to avoid any patent disputes. It further borrowed its gas-operated, blow-forward design from the semi-automatic Bang rifle of 1903, where the gas piston blew forward instead of backward, while the Hotchkiss bolt was discarded and a Maxim-style toggle was added.

It was a complicated machine gun, but it was a truly French designed, which satisfied Paris.

However, the St. Étienne Mle 1907 was arguably one of the worst machine guns to see service in the First World War, where its complex operating system often jammed if one looked at it wrong. In the muddy conditions, it was a disaster waiting to happen. The weapon was later supplied to French allies while many were sent to the French Foreign Legion.

The Mle 1914

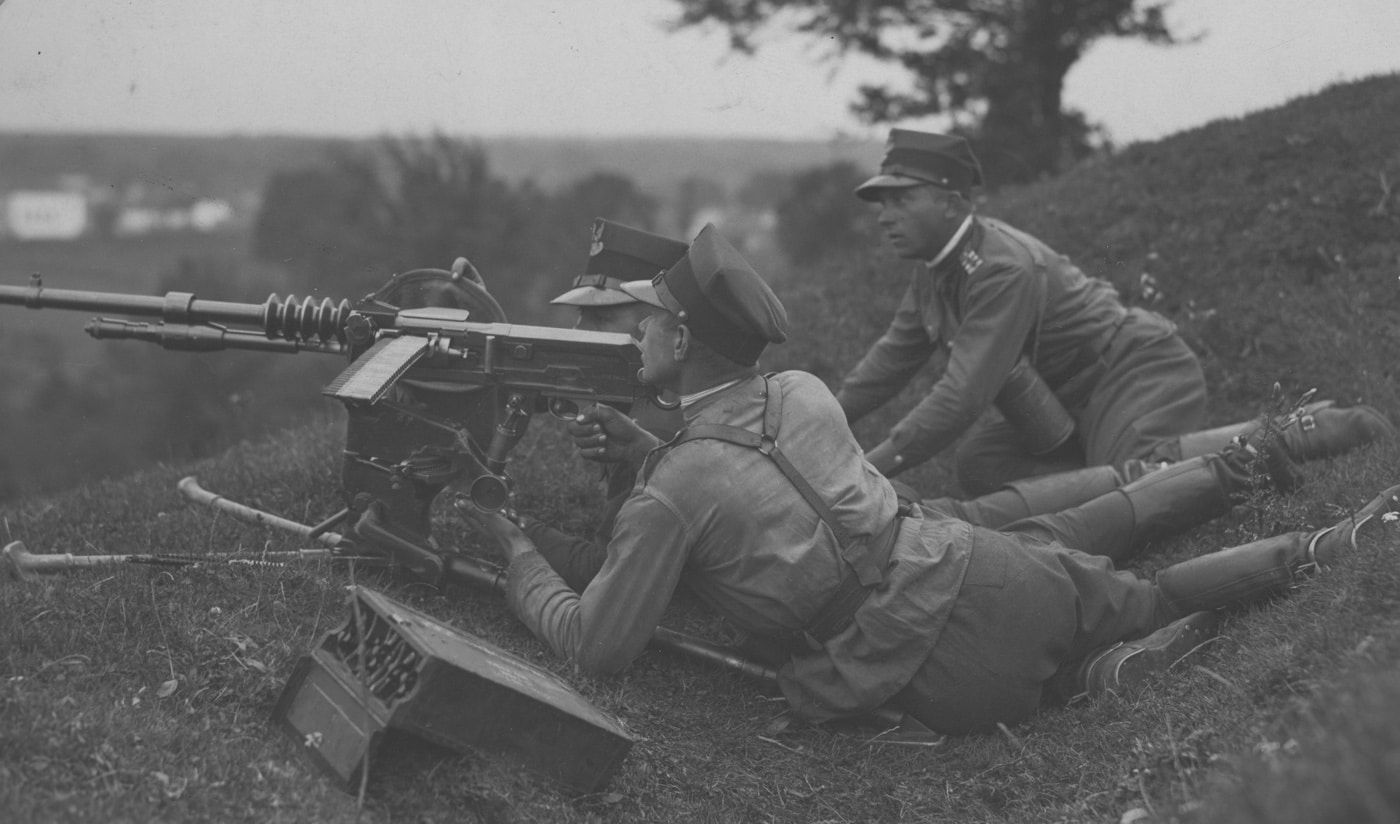

When the First World War broke out the French military found itself literally fighting for its life. It needed every weapon it could get, and it opted to adopt the Hotchkiss Mle 1900 with a few changes, and thus the Mitrailleuse Automatique Modèle 1914 entered service. For political reasons, it was widely employed by second-line troops initially, but a parliamentary committee of inquiry determined that the Hotchkiss design was superior to the St. Étienne Mle 1907.

By 1916 it had become the main frontline machine gun of the French Army. It proved to be a reliable, albeit heavy and bulky machine gun. Not all of its quirks had been fully addressed, however.

Where other machine guns were belt-fed, the Hotchkiss employed stamped steel or brass feed strips that held either 24 or 30 rounds. In theory, the strips could be linked by the assistant gunner as the weapon fired, providing a continuous stream of lead flying down range.

That proved to be harder to accomplish in combat than the designers might have expected. But that was probably a good thing.

In sustained fire in the trenches the barrel could glow red-hot despite the cooling fins. The weapon could continue to operate, but once completely overheated the only option was to let it cool as the barrel couldn’t be changed while hot. In fact, the guns were pushed to the breaking point so often that Hotchkiss machine guns with worn barrels were often sent to rear areas to receive a new barrel.

Nearly 50,000 were delivered to the French Army by the end of the war, and the Mle 1914 remained in service until 1945.

Foreign Service and the Hotchkiss

It wasn’t just the French that employed the Mle 1914 in the latter half of the First World War. Twelve divisions of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in France were also equipped with the weapon. Interestingly, while the French were able to supply the Hotchkiss to the U.S. for training, it couldn’t provide tripods.

During the conflict, the French military largely used one of two basic tripod types, when the final and most effective third Hotchkiss tripod model (the Mle 1916) became adopted and widely distributed.

However, the AEF adopted a third type of tripod — also known as the Model 1916 — which was produced by The Standard Parts Company of Cleveland, Ohio. Approximately 2,500 were manufactured, and it remains unclear how many were actually sent to France.

Most were scrapped after the war, and it is extremely sought after by collectors today given that only a few hundred are known to have survived.

Conclusion

Following the end of the First World War, Mle 1914s were provided to China, Czechoslovakia and Poland — while numerous nations in Latin America also adopted the machine gun. It was produced under license in Japan and went on to evolve into the Type 3 and Type 92 heavy machine guns.

The combat history of the Hotchkiss series of machine guns is mixed. It was fairly easy to maintain, but heavy. It didn’t require a bulky water jacket, but it could quickly overheat. Its greatest legacy is that it was arguably the first successful and lasting alternative to the Maxim.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

92

92