Independence-Class Aircraft Carriers — America’s Forgotten Warriors

August 19th, 2023

10 minute read

With war on the horizon, President Franklin D. Roosevelt supported a plan to convert a number of Cleveland class light cruisers into light aircraft carriers. Called the Independence Class, these “new” flattops were meant to augment the U.S. Navy until the newer, larger Essex class carriers could come online. Within six months of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, America reordered nine cruisers as Independence-class carriers with the first commissioned in January 1943. Though they were small aircraft carriers, these nine ships played an important role in the Allied victory during WWII. Peter Suciu tells us their story.

As the clouds of war appeared on the horizon in the late 1930s, the United States Navy began the development of the Essex-class aircraft carrier — a new breed of fleet carriers that went on to be the workhorses of the Second World War. These flattops would serve in the Pacific as floating airfields that helped the U.S. defeat the Empire of Japan.

However, the Essex-class vessels were large and complex ships, and as a result, there were fears during their development that that the U.S. Navy wouldn’t have the necessary flattops ready in time. With none of these new fleet carriers expected to arrive until 1944 and a limited number of in-service carriers bearing the brunt of the fight, President Franklin Roosevelt — who had previously served as assistant secretary of the navy — proposed converting a number of cruisers then under construction into light carriers.

The plan had its pros and cons.

Such conversions had actually resulted in the pair of Lexington-class aircraft carriers — USS Lexington (CV-2) and USS Saratoga (CV-3) — which had each been originally laid down as battlecruisers after the First World War. The conversation had come about as a result of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, which limited the total tonnage allowed for traditional warships leading up to World War II. In addition, the USS Langley (CV-1) — the Navy’s first aircraft carrier — was converted from the USS Jupiter (Collier #3) in the early 1920s.

These early U.S. Navy carriers proved vital in the development of carrier aviation tactics.

USS Langley (CV-1) was later reclassified as a seaplane tender (AV-3), and supported seaplane patrols and aircraft transportation until she was attacked by Japanese aircraft in late February 1942, and subsequently scuttled. The Lexington was sunk just months later during the Battle of the Coral Sea, the first carrier engagement in history, while the USS Saratoga survived the war despite being seriously damaged on no less than three occasions.

In addition, another successful conversion resulted in the development of the Long Island-class escort carriers that were converted from C3-class merchant ships. The conversions of two ships took fewer than six months to complete.

Thus, the concept to convert cruisers to stopgap carriers had merit, at least in concept.

Though it had the support of Roosevelt, the admiralty noted several limitations and actually objected. One issue was that the carriers would be too small to carry a significant airwing, and it was not seen as compatible with the U.S. Navy’s air-naval doctrine at the time. However, the order still came from the president — aka the commander-in-chief — so there was no actual discussion.

BuShip Studies on Conversions

The U.S. Navy directed the Bureau of Ships (BuShip) to begin studies for a cruiser-sized aircraft carrier. One of the initial proposals called for a conversion from the Pensacola-class cruisers — the first “treaty cruisers” as these were based on the limitations imposed by the interwar naval treaties. Not surprisingly the plan was immediately met with pushback from the General Board of the United States Navy, which placed a veto on the proposal.

The thinking was that such a conversion resulted in too many compromises for the ship to be effective. It was argued that it would be a waste of time and resources, each of which could be directed elsewhere. But Roosevelt was determined that the U.S. Navy needed carriers quickly and pressed for the admiralty to find a way of making a conversion happen.

Roosevelt ordered another study.

The BuShips worked around the clock — finding ways to include a hanger that could accommodate a larger air group. The second study was then submitted to the admiralty, which deemed it of a “lesser capability” than desired, but it would be available sooner.

The discussions were actually ongoing when the Imperial Japanese Navy launched its sneak attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. That event completely changed the dynamic and the U.S. Navy’s admiralty quickly recognized that more carriers were needed, and as quickly as possible. U.S. Navy officials went on to approve the second proposal but also recommended that all efforts be made to accelerate the construction of the Essex-class aircraft carriers. Believing that the Essex-class still couldn’t arrive until at least late 1943, efforts were also directed at converting a number of Cleveland-class light cruisers into carriers.

In hindsight, it remains a questionable decision.

Meet the Independence-Class

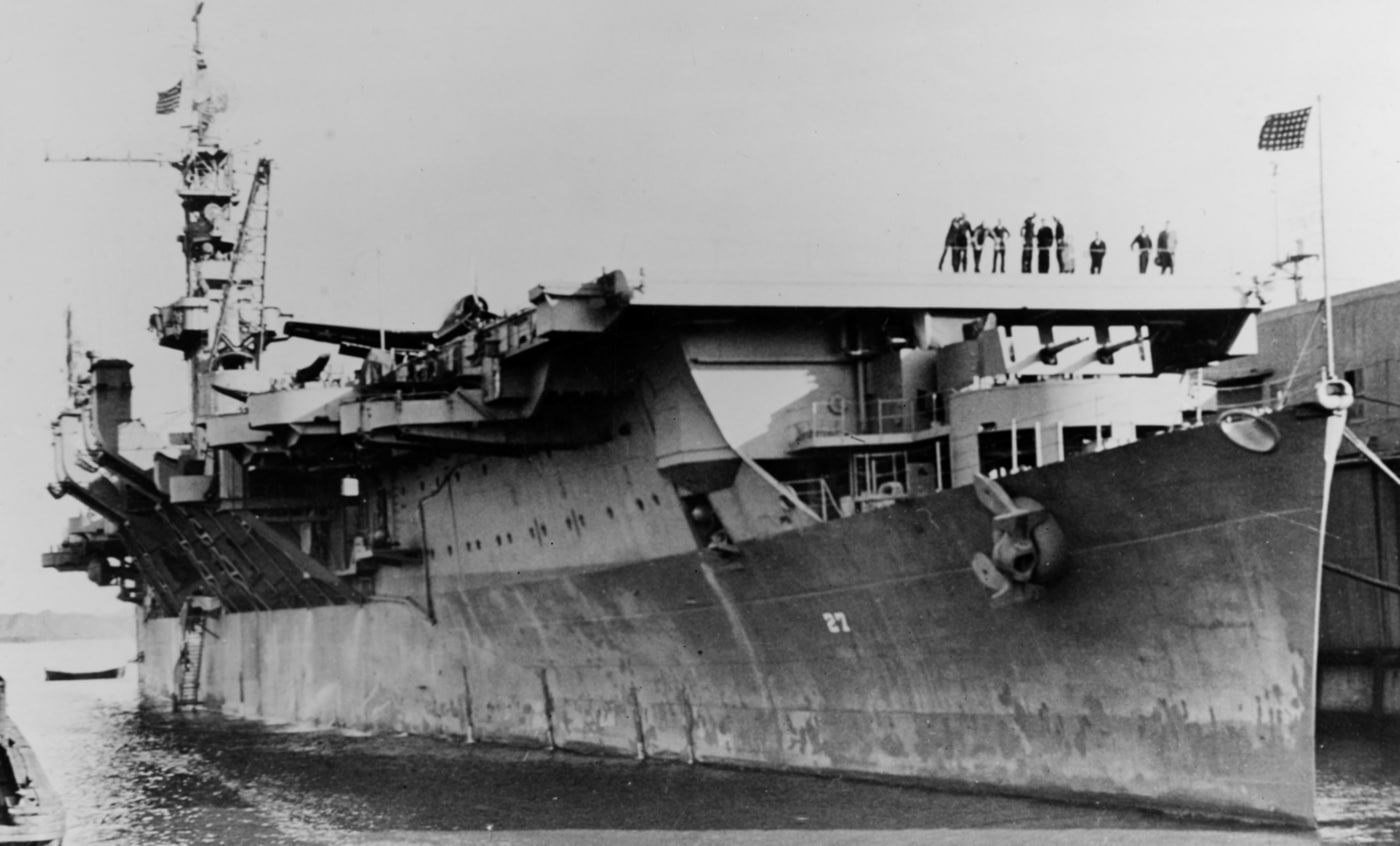

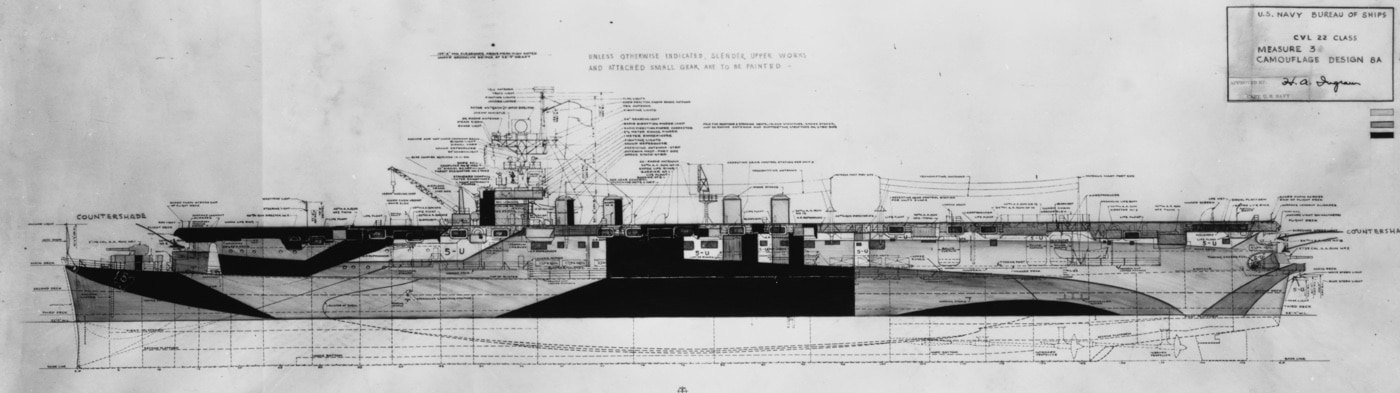

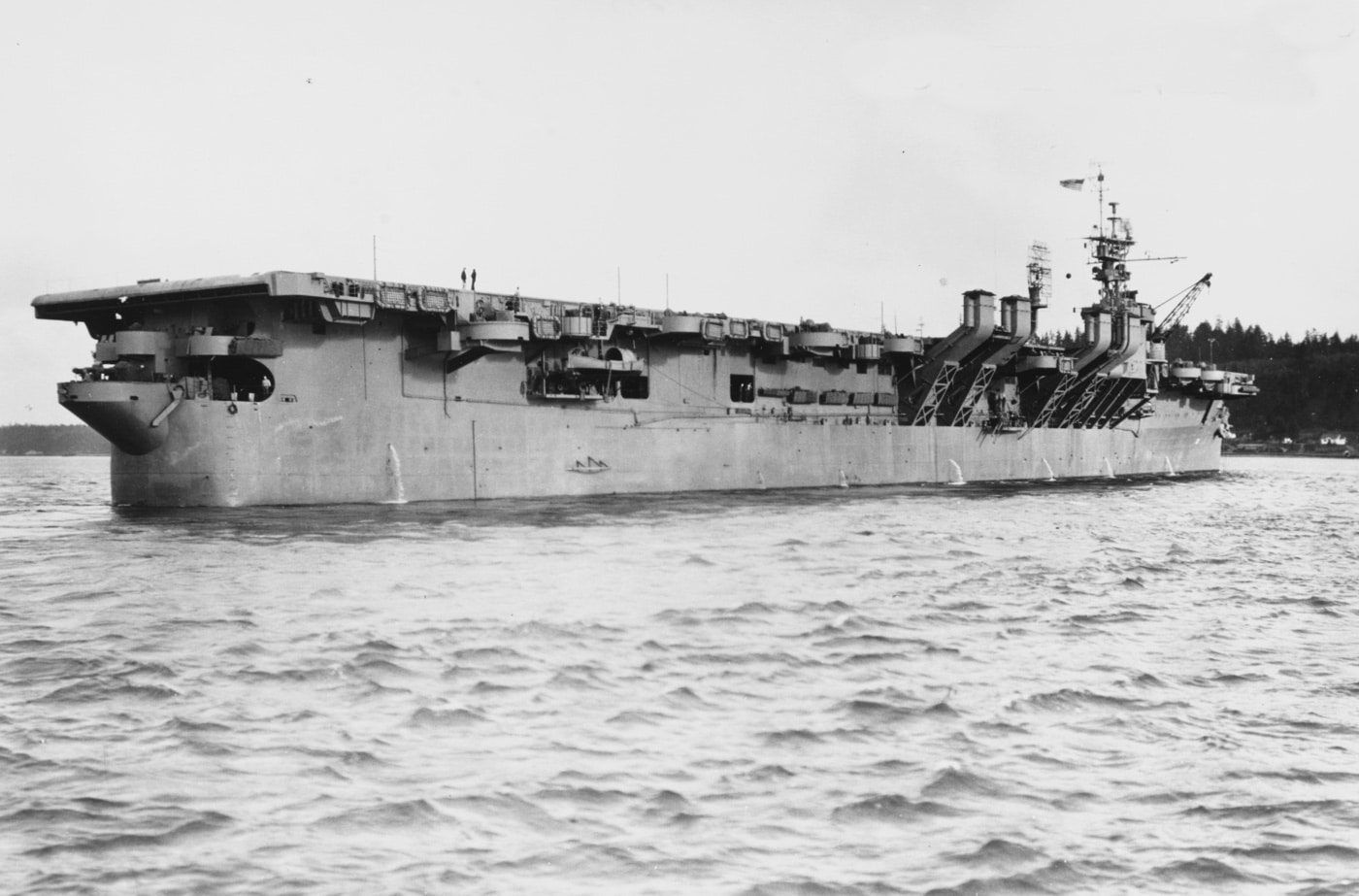

Nine hulls were eventually requisitioned at the New York Shipbuilding Corporation Naval Yard in Camden, New Jersey. The soon-to-be-named Independence-class carriers were equipped with a relatively short and narrow flight deck and hanger, as well as a small island superstructure. As all of that resulted in a significant increase in topside weight, the carriers’ beam was increased with the addition of blisters, which provided extra buoyancy as well as greater protection from torpedoes.

The flight deck allowed aircraft to be parked on each broadside while still allowing aircraft to take off and land. The hanger could hold 30 aircraft — one-third that of an Essex-class air group.

No one would likely call the Independence class a handsome vessel. The ships were boxy and were arguably an evolutionary step backward in naval design, but they were seen as better than nothing at a time when the U.S. Navy had few carriers.

The Battle of Midway in June 1942 changed the dynamic considerably, but by that time construction was well underway on the light carriers.

Arrival of the Converted Carriers

The lingering question is whether the Independence class was actually a wasted effort. A total of nine were built with all entering service in 1943 — so they offered essentially the air power of three Essex-class. That could be seen as a fair tradeoff, but the first in class, USS Independence (CVL-22) — the former Amsterdam — was launched in August 1942, completed in December of that year, and then finally commissioned in August 1943.

By that time USS Essex (CV-9) was also in service, thanks to an accelerated construction.

The bigger issue was that sacrifices that were made to build the carriers so quickly also meant that they weren’t well suited to the Pacific typhoons, while the small flight deck made operations difficult. Even with a smaller air wing, the accident rate was higher on the light carriers. For those reasons, “rookies” were often sent to the new Essex-class CVs rather than the CVLs.

The Independence class, as it was based on light cruisers, did prove to be speedy ships — faster than the U.S. Navy’s Casablanca-class escort carriers (CVE). The carriers went on to make up a vital component of the Fast Carrier Task Force, which took part in the Navy’s campaign through the central and western Pacific from November 1943 through August 1945. In addition, eight of the light carriers also participated in the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944, which effectively ended the Imperial Japanese Navy’s carrier air power.

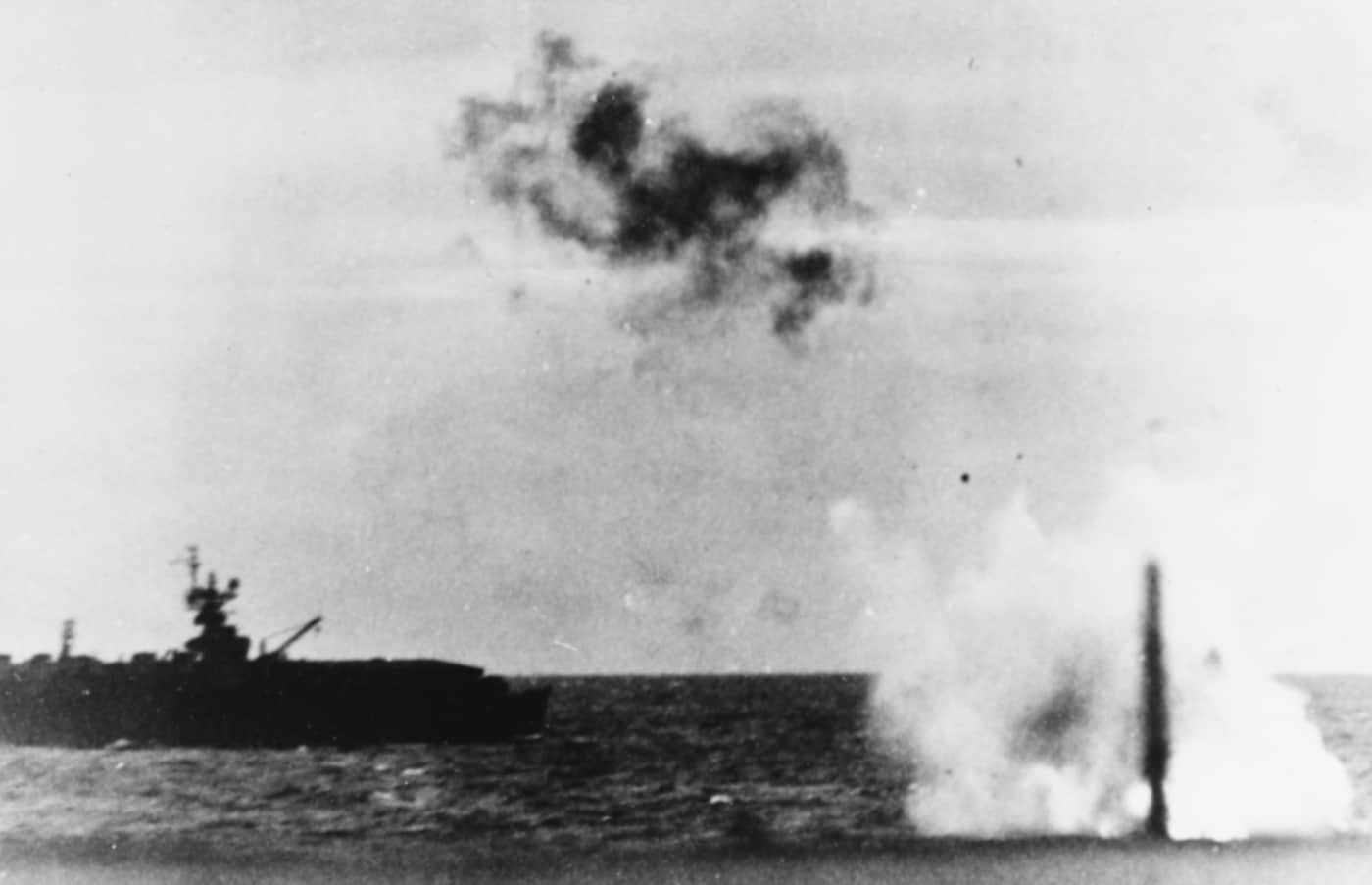

Only one of the Independence-class carriers was lost during the war, the USS Princeton (CVL-23) — the former Tallahassee. She was severely damaged during a Japanese air attack during the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944. A dive bomber dropped a single bomb that struck the carrier between the elevators, punching a hole through her wooden flight deck.

Though the structural damage was actually minor, a fire broke out and quickly spread. Her former sister ship, the cruiser USS Birmingham (CL-62) aided in the firefighting, but a second and far larger explosion occurred — likely the result of a bomb in the magazine “cooking off.” Both ships suffered extensive damage, and while efforts continued to save the light carrier, a decision was made to scuttle her. She had still earned nine battle stars for her service.

Given their short history during the latter stages of the Second World War, it is still hard to say if the U.S. Navy could have lived without the carriers. Though these nine vessels did play a significant role in the war, it is likely the Navy could have gotten another Essex class or two instead from the same production effort.

Post-War Needs, or Not?

Though eight of the Independence-class carriers survived the war, these had truly been stopgaps for the U.S. Navy, which had no need for the Independence-class in the post-war era. All were decommissioned as the service returned to peacetime levels.

The lead vessel of the class, USS Independence (CVL-22) was used as a target ship during the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests at the Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. She actually survived the nuclear blast and was later used as a radiation research hulk for several years. The retired warship was finally expended as a target and scuttled off San Francisco in 1951.

USS Cowpens (CVL-25), USS Monterey (CVL-26), USS Bataan (CVL-29), and USS San Jacinto (CVL-30) were all decommissioned after the end of the war and sent to the reserve fleet. Each was eventually broken up, with CVL-30 being scrapped in 1971.

In addition, USS Belleau Wood (CVL-24), and USS Langley (CVL-27) were transferred to France and served in the Marine Nationale — as the Bois Belleau and La Fayette respectively — until the late 1950s when they were each returned to the United States and subsequently scrapped.

The USS Cabot (CVL-28) actually had the most colorful post-WWII career. She was transferred to Spain after World War II and was recommissioned as the Dédalo, and served for several decades with the Spanish Navy, being modernized to operate the SpAV-8S Matadors, the Spanish version of the AV-8A Harrier. This required that the wooden flight deck was covered with protective metal sheathing. During her service, Dédalo logged 1,650 days steaming, covering 300,000 nautical miles (560,000 km), registering 30,000 landings and takeoffs, while also losing an AV-8A and three AB 212ASW helicopters to accidents.

Dédalo was retired from the Spanish Navy in August 1989, and there were actually efforts in the United States to convert the conversion vessel to a museum ship. However, that fell through and when the private organization that owned the ship was unable to pay its creditors, the World War II warship was auctioned off by the United States Marshals Service. Sabe Marine Salvage of Rockport, Texas purchased the warship and completed the scrapping in 2002 — thus closing the book on the history of the Independence-class carriers.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

415

415