Japanese Body Armor in World War II

March 12th, 2024

8 minute read

While Japan focused on the “spirit of Bushido” and counted on the aggressive fighting spirit of the Emperor’s soldiers, there were still efforts made to protect their men from superior Allied infantry firepower.

During WWII, the Japanese created several types of body armor, and while these designs had minimal impact on the battlefield, they did have a strong influence on American body armor after the war.

Types of Japanese Body Armor

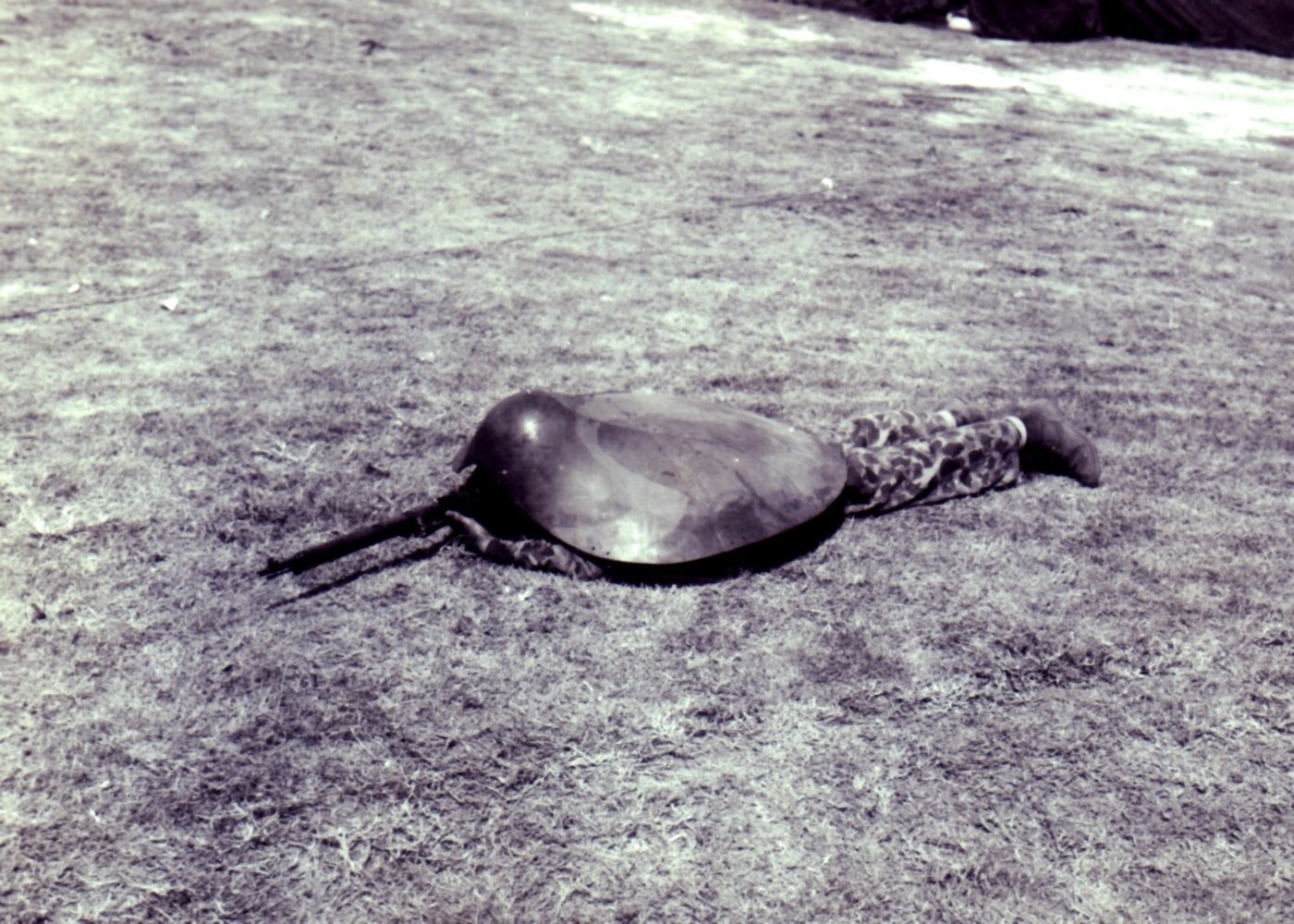

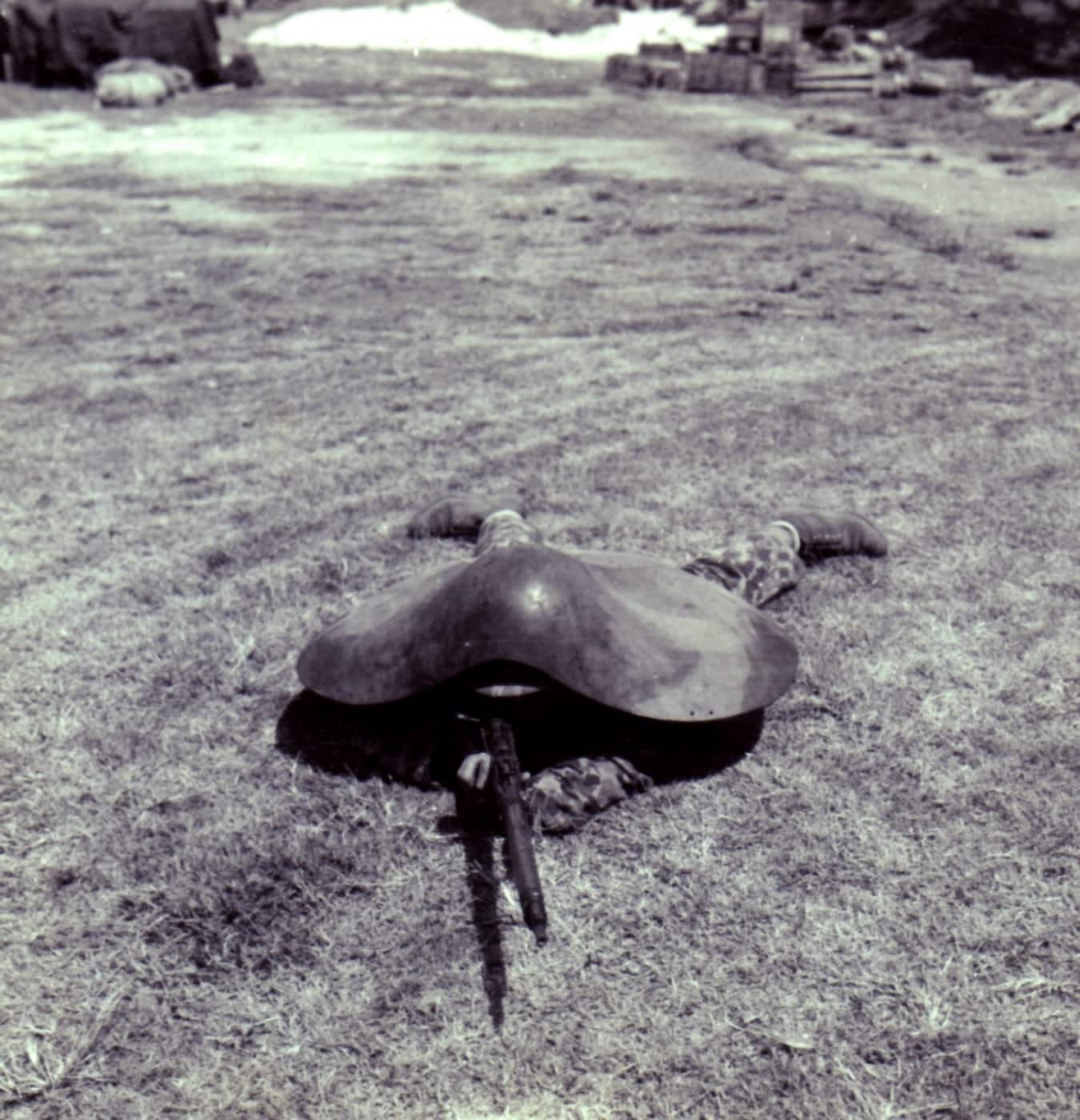

The first Japanese body armor design that caught American attention was actually a light armored shield that looked much like a turtle shell. Consequently, U.S. troops called it “turtle armor,” while the Japanese called it “tortoise armor.” A U.S. Ordnance Technical Intelligence Report created in Tokyo during January 1946 provides a little insight into this unique form of personal protection.

Body Armor: During the years 1938 to 1940 several types of body armor were proposed and made. One type mounted a light machine gun and had small wooden wheels. The maneuverability of this type being very poor, a second type which could be fastened to a man’s back, was introduced. This was called the “Tortoise Armor”. Interest in this project ceased in about 1940 and further research was abandoned.

U.S. Ordnance Technical Intelligence Report, January 1946

What few pieces of the tortoise armor was created must have been shipped to the defenders of Saipan, with at least one example captured by the USMC.

The most commonly encountered “personal armor” fielded by the Japanese were the armored shields developed for riflemen and light machine gunners. The small shields had been in use by various nations since World War I, and were still seen in use (usually in static-warfare conditions) on the Russian Front. American troops were mildly surprised to find them, and after they tested the shields, they wondered why the Japanese bothered to issue them at all.

The U.S. Army described these devices:

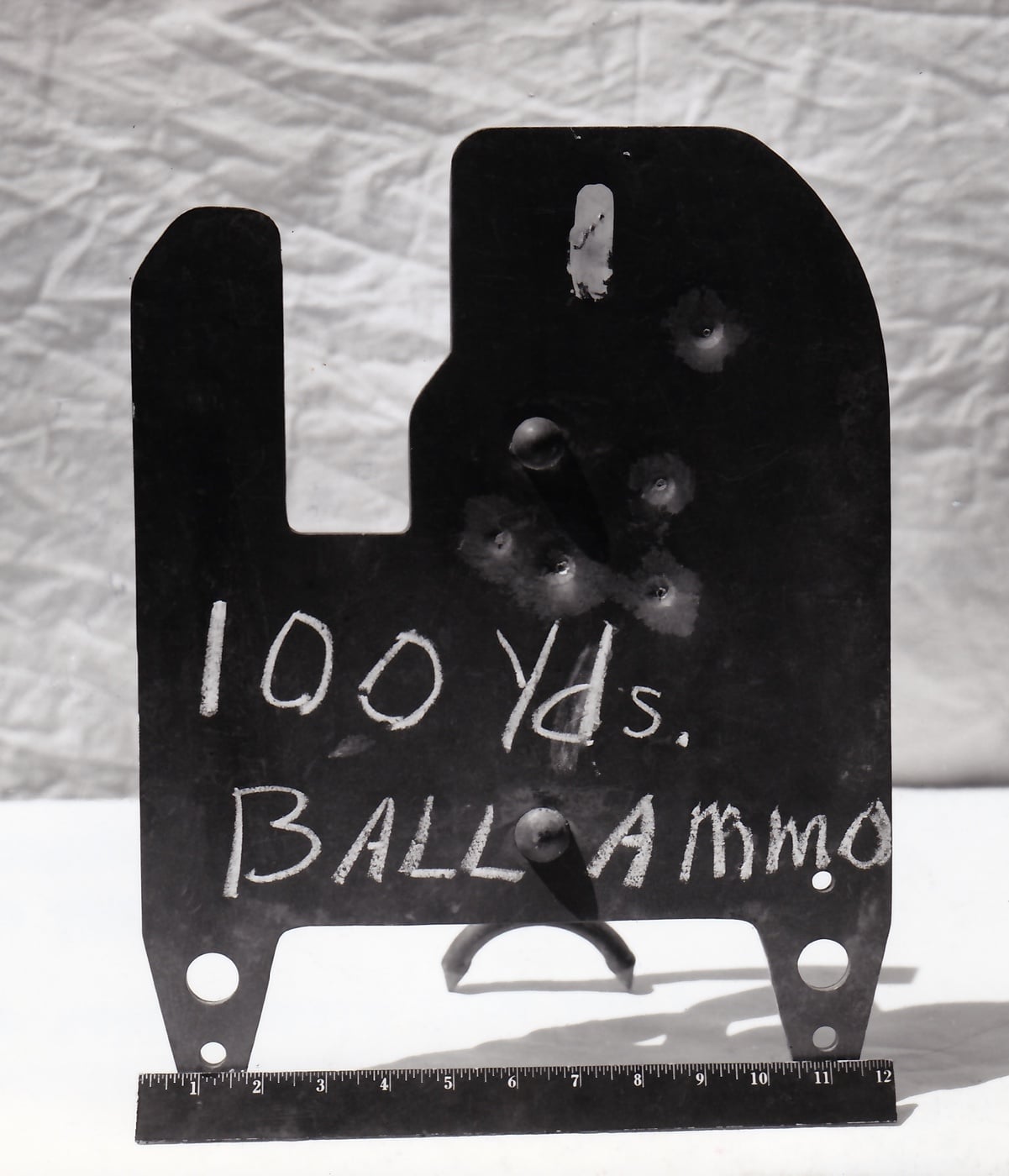

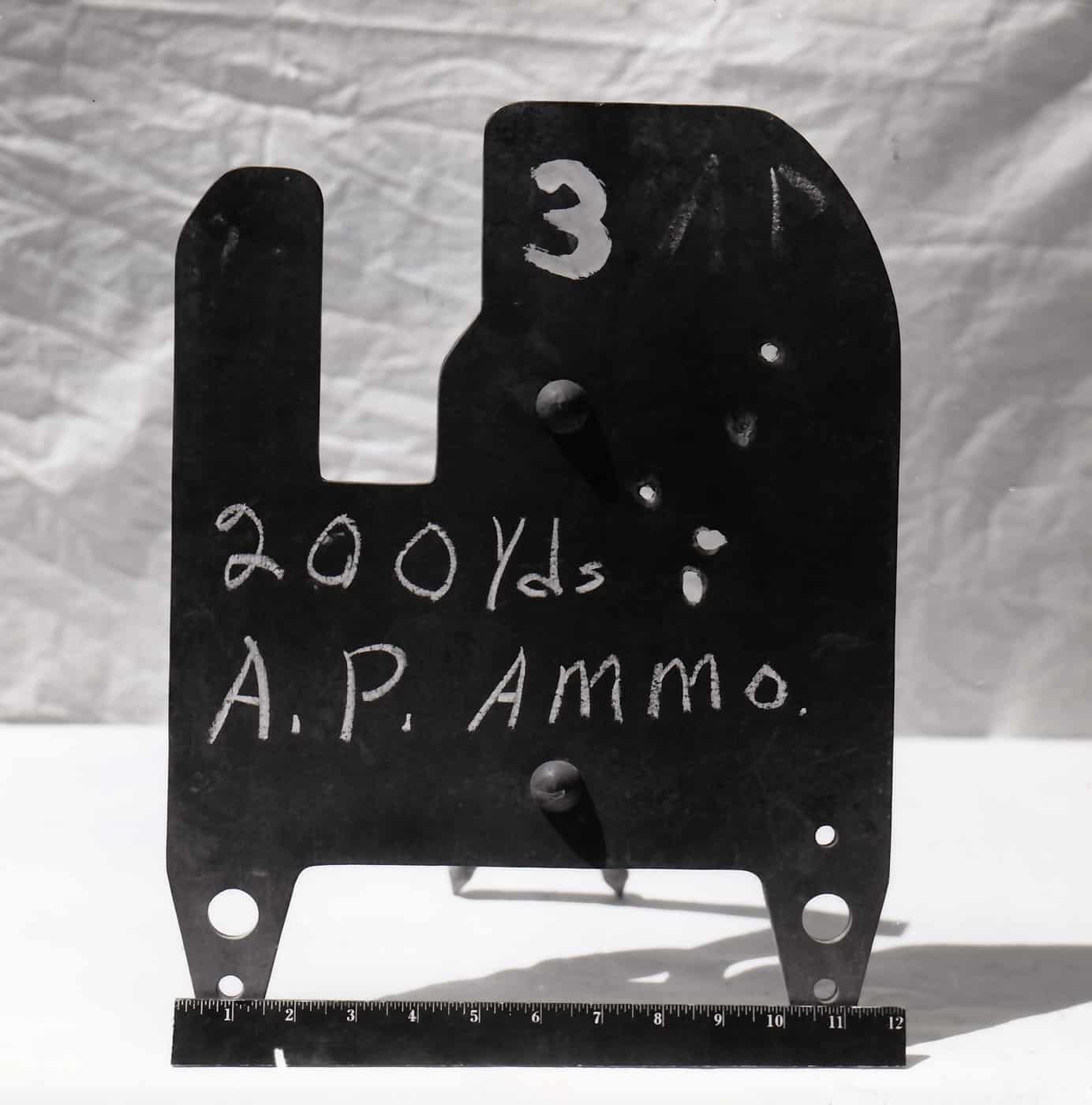

Armored shields: While these shields are suitable for use in the open, specimens constructed from what appears to be face-hardened plate have been found built into the weapon ports of pillboxes. Two sizes have been recovered, the larger measuring 14 x 20 x ¼ inches, and the smaller 12 x 16 x ¼ inches.

Penetration: Tests have shown that these shields will resist penetration by .30 caliber ball ammunition at 100 feet. However, some damage may be caused by flaking (chipping). These shields have been penetrated readily by .30 caliber AP ammunition at up to 200 yards.

Handbook on Japanese Military Forces (1944 Edition)

Some have described the Japanese rifle shields as sniper equipment. Based on Japanese sniper doctrine this seems unlikely — their focus on stealth and concealment tends to preclude dragging around several pounds of an armored shield.

Photos show some use of the armored shields incorporated into Japanese pillboxes and bunkers, but their inability to resist even standard US .30 caliber ball ammunition at anywhere short of 100 feet makes them of dubious effectiveness.

Japan’s Bulletproof Vest

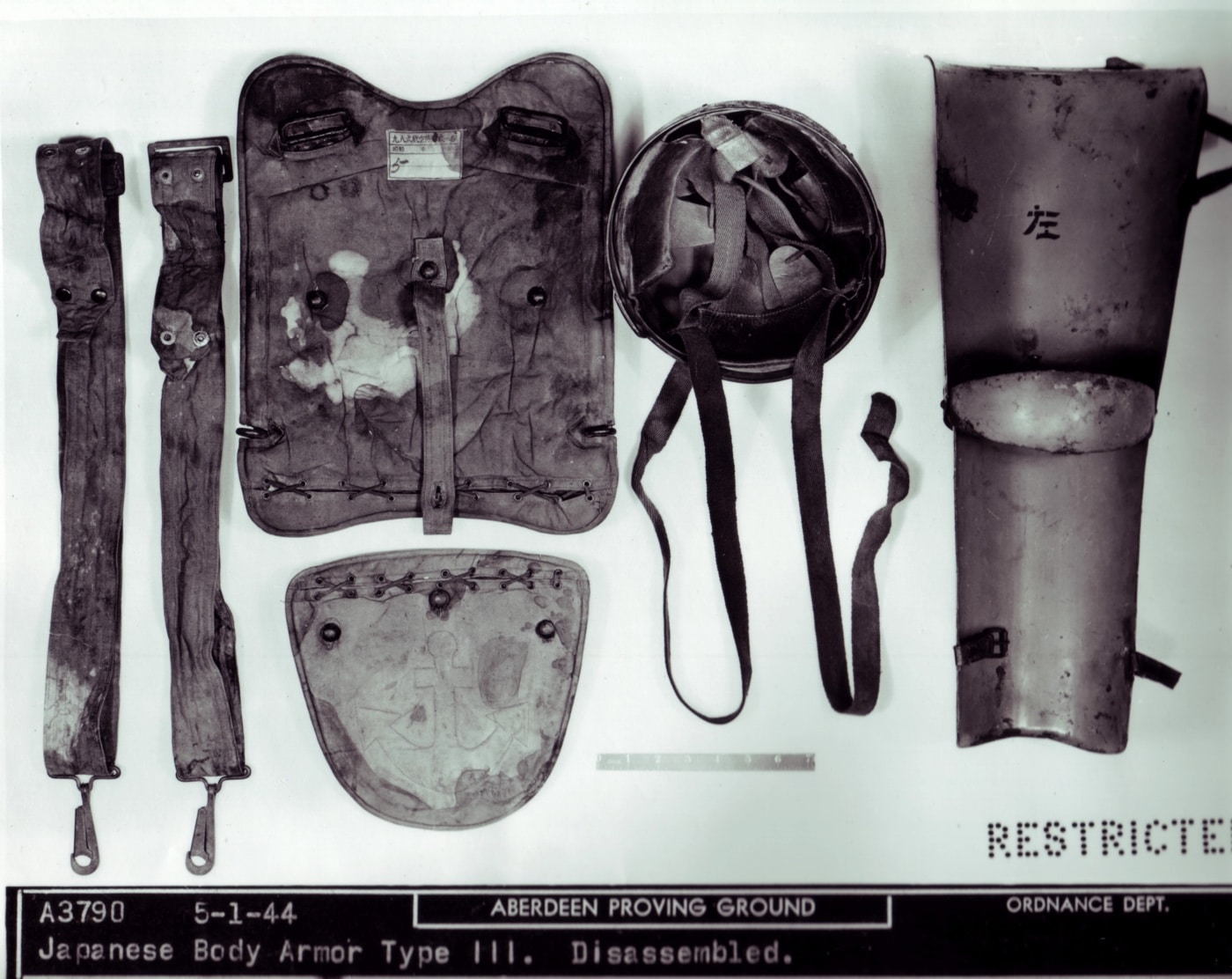

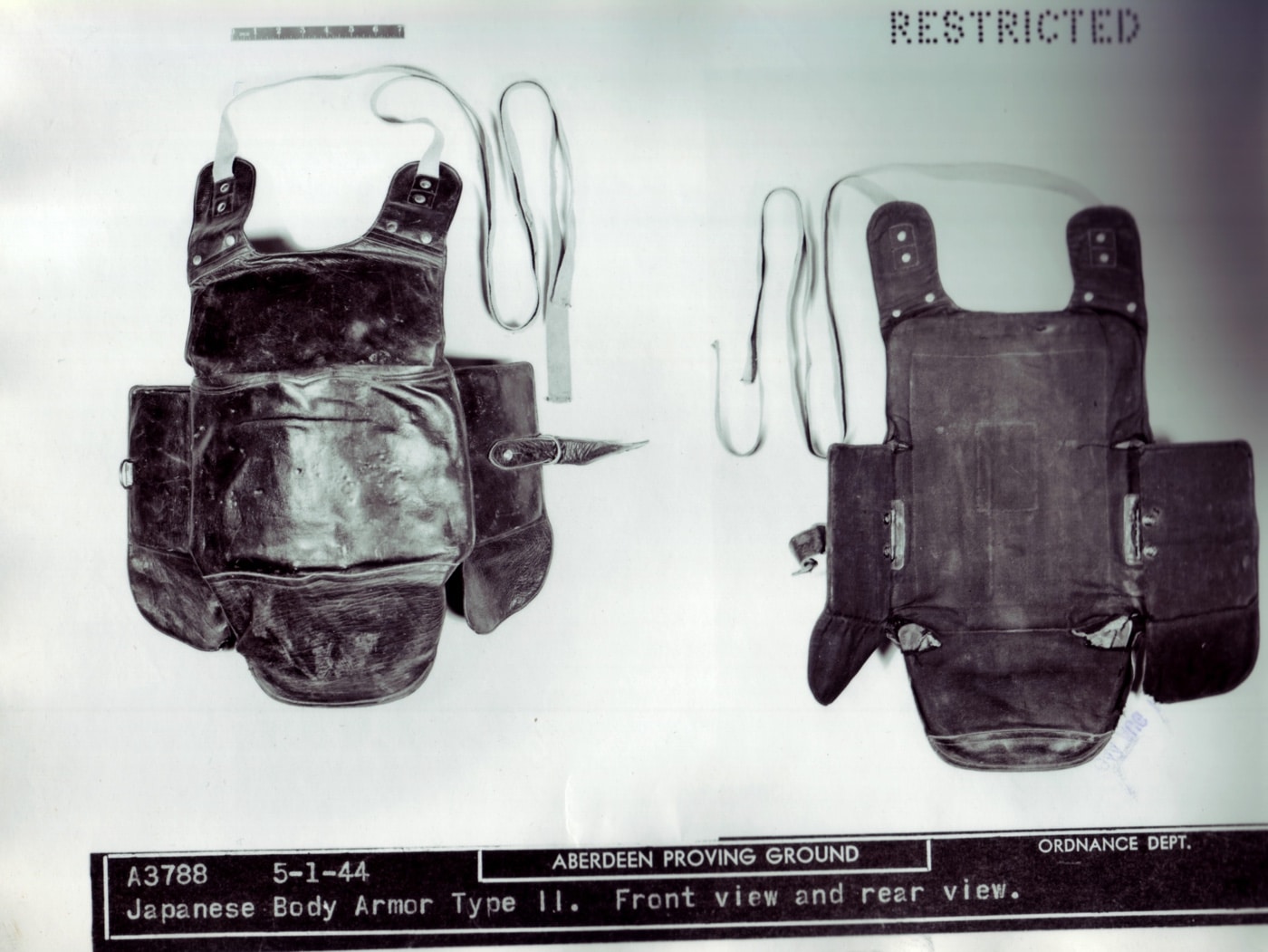

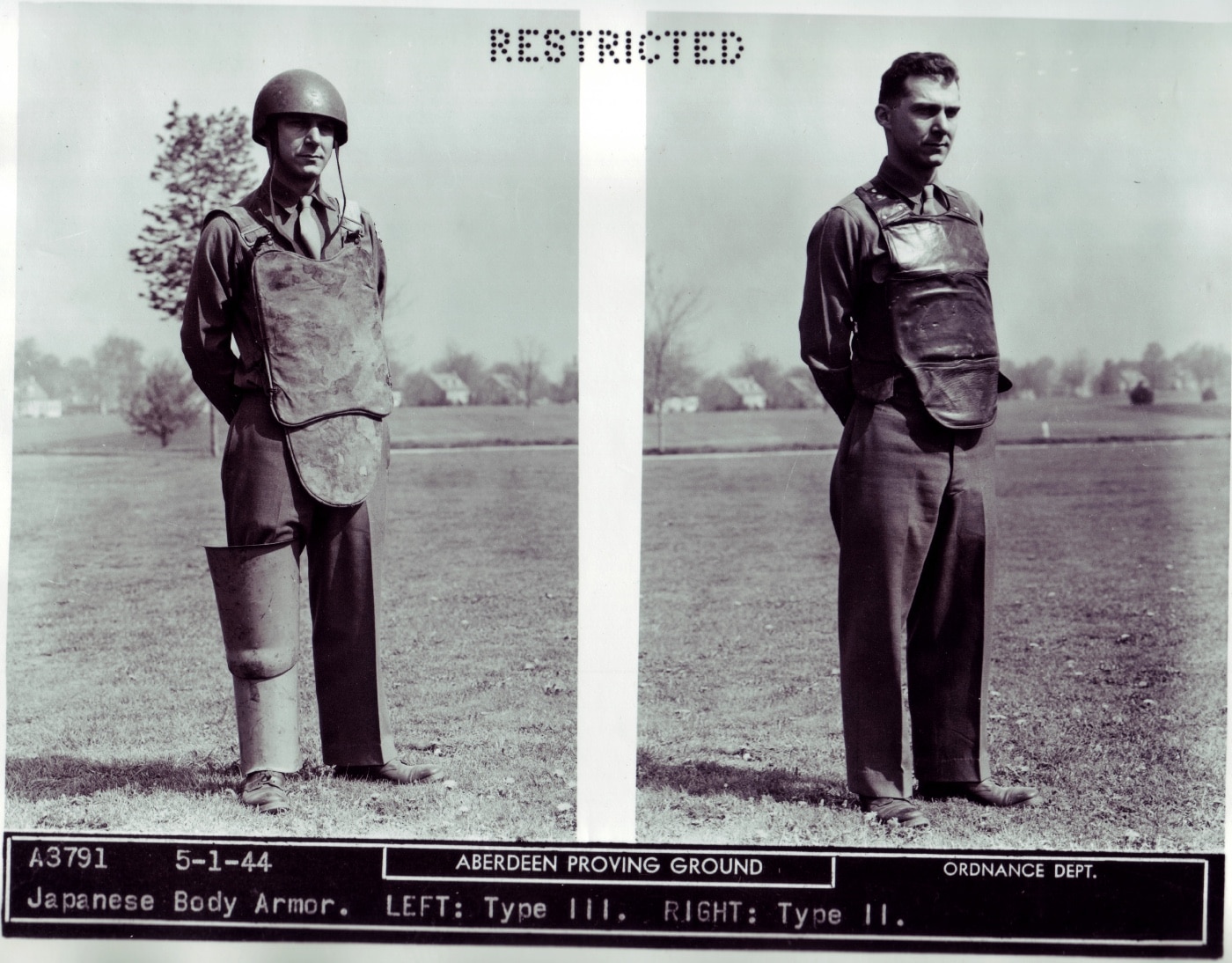

The final types of Japanese body armor were two variants of a bulletproof vest, one of which included an armored helmet and form-fitting leg protection.

The 1944 Handbook on Japanese Military Forces provides this description:

Bulletproof vest: The vest is made from olive green drill cloth with three pockets on each side to accommodate armor plates arranged in a fish-scale fashion. Characteristics are as follows:

Weight, complete: 9 pounds

Thickness of plates: 0.08 inches

Plate overlap: 0.05 inches

It is believed that the weight of this vest would preclude its general use by the infantry and probably would tend to confine its use to special troops. Tests have shown that the plates are penetrated easily by .30 ball ammunition at 100 yards range, with a 30-degree angle of impact from normal.

An example of the Japanese armored vest was tested at Aberdeen Proving Grounds during July 1943. The armor was given a thorough chemical analysis, and was determined to have “a rather high hardness was obtained (401 Vickers Brinell)”, while the Japanese manufacturers had “obtained maximum toughness at an appreciable hardness level.”

The Aberdeen report concluded that “The ballistic properties of this armor were reported to be excellent.”

Compelling Medical Data

As WWII continued, U.S. forces were seriously looking into the benefits of a light armored vest for use by combat troops. Examples of the Japanese armored vests influenced American designs, and U.S. medical services provided useful data that gave this development a greater sense of urgency.

The first evidence can be found here:

Body Armor: A practical type of body armor has been developed largely through the work of Lt. Comdr. A. P. Webster and Lt. Comdr. E. L. Corey of the Research Division of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. It can be incorporated into the standard life jacket or the Marine Corps utility jacket. The design of the basic garment is not altered, with sheaths similar to large patch pockets being sewn into the jacket for the reception of appropriately designed slabs of a plastic armor material. The armor adds about four pounds to the weight of the garment and increases its bulk very little. In wearing the jacket comfort and freedom of movement are not adversely affected. While the armor is held securely in place when inserted into the sheaths, it can be removed quickly at will; thus, damaged parts can be replaced and laundering of the jacket can be accomplished without difficulty.

The armor was designed primarily for protection against fragments. However, it is not penetrated by a direct hit by a bullet fired at a distance of fifteen feet from a .45 service automatic pistol or from a Reising or Thompson submachine gun. Armored life jackets of this kind are being procured by BuShips and will be issued to various types of vessels in the near future. Field trials of the armored Marine Corps utility jacket are being carried out.

U.S. Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Newsletter, November 1944

Some interesting, and quite compelling data supporting the use of body armor was published here: “Bulletin of the U.S. Army Medical Department” during March 1945:

A study of the effect of wearing body armor by comparing experience before and after its introduction, and the experience of two groups of heavy bomber combat crew members, one wearing armor and the other not wearing armor, indicates the following: (1) Since the introduction of armor, there has been a reduction of 58 percent in individuals wounded and 60 percent in wounds sustained. At least part of this reduction is considered attributable to the wearing of armor. (2) A study of the location of wounds sustained indicates a reduction of 14 percent in wounds of the head and neck, 58 percent in wounds of the thorax, and 36 percent in wounds of the abdomen. (3) Comparison of individuals struck while wearing armor with those struck while not wearing armor shows a reduction of fatality of thoracic wounds from 36 to 8 percent, and of abdominal wounds from 39 to 7 percent. (4) Body armor prevents about 74 percent of wounds in covered areas.

Bulletin of the U.S. Army Medical Department, March 1945

Battlefield Use

In the last few months of WWII, the U.S. sent a few examples of the M-12 armored vest and its related “T-65 Apron” to the PTO for testing. The M-12 weighed in at 12 pounds, using aluminum plates sewn into a nylon vest. The T-65 Apron provided additional protection for the groin. No meaningful combat testing was completed before the war ended, and the Army considered body armor for combat troops to be impractical based on its weight. Consequently, M-12 vests were intended for use by mine-sweepers and ordnance removal specialists.

When the war in Korea began, there was a sudden call for body armor among U.S. troops. The “too-heavy” M-12 was issued as a stopgap until lighter designs could be created. Within a year, a U.S.M.C.-U.S. Army team produced the M-1951 vest that used “Doron”, a laminated fiberglass compound that provided good protection with lighter weight (the M-1951, sometimes called “the Marine Vest”, weighed slightly less than 8 pounds).

During 1952, the Army produced the M-1952 Body Armor, Fragmentation Protective. The 8 ½-pound M-1952 was a more modern design that used laminated nylon to provide a more flexible and effective form of personal protection. Small amounts of M-1952 vests reached the troops beginning in late 1952, and the design remained in service through the Vietnam War.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

82

82