M18A1

Claymore Mine:

From Vietnam to Today

June 24th, 2023

8 minute read

Aimed in the right direction, the U.S. M18A1 Claymore mine is one of the most lethal and devastating anti-infiltration weapons of modern warfare. There’s a reason for the qualifier on that kudo, and more about that in a moment. From its initial employment with U.S. forces in the mid-1950s, the Claymore gave infantry units a reliable and deadly device that could be used in perimeter defense or offensively as an ambush trigger.

The Claymore, named after the Scottish broadsword that cut bloody swaths through enemies, garnered infamy and worldwide recognition employed for those same purposes in Vietnam.

A New Path for Anti-Personnel Mines

Most mine-type weapons direct explosive power upward and are usually initiated when a man or a vehicle steps on or rolls over a buried or hidden trigger. However, the M18A1 Claymore is a truly directional mine. This means the user can aim the blast as desired.

A claymore mine is typically command-detonated via wire crimped to an M4 electrical blasting cap. The detonation is initiated by an M57 squeeze-type firing device (often called a “clacker” for the snapping sound it makes when squeezed to fire the mine), which sends an impulse to the blasting cap and detonates the Claymore.

The Claymore package as used in Vietnam, came wrapped in an M7 OD bandolier and weighed in at about four pounds with all components present, including the mine, clacker and 100 feet of wire. The wire was wrapped around a plastic spool, with one end featuring the blasting cap and the other a plug for connecting to the firing device. A printed instruction sheet was sewn into the flap of the Claymore bag for those who slept through the block of instruction for using the mine.

One of the most appealing features of the Claymore is its flexibility. Soldiers can fix it around the perimeter of a position and detonate it remotely as required to prevent infiltrators, or they can use it to sweep trails in order to stop enemy traffic and disrupt resupply or reinforcement efforts. It can also be daisy-chained or attached to other mines for sympathetic detonation to cover a wider area. Employment of the Claymore is really only limited by the soldier’s devious ingenuity.

Directional Mines In Practice

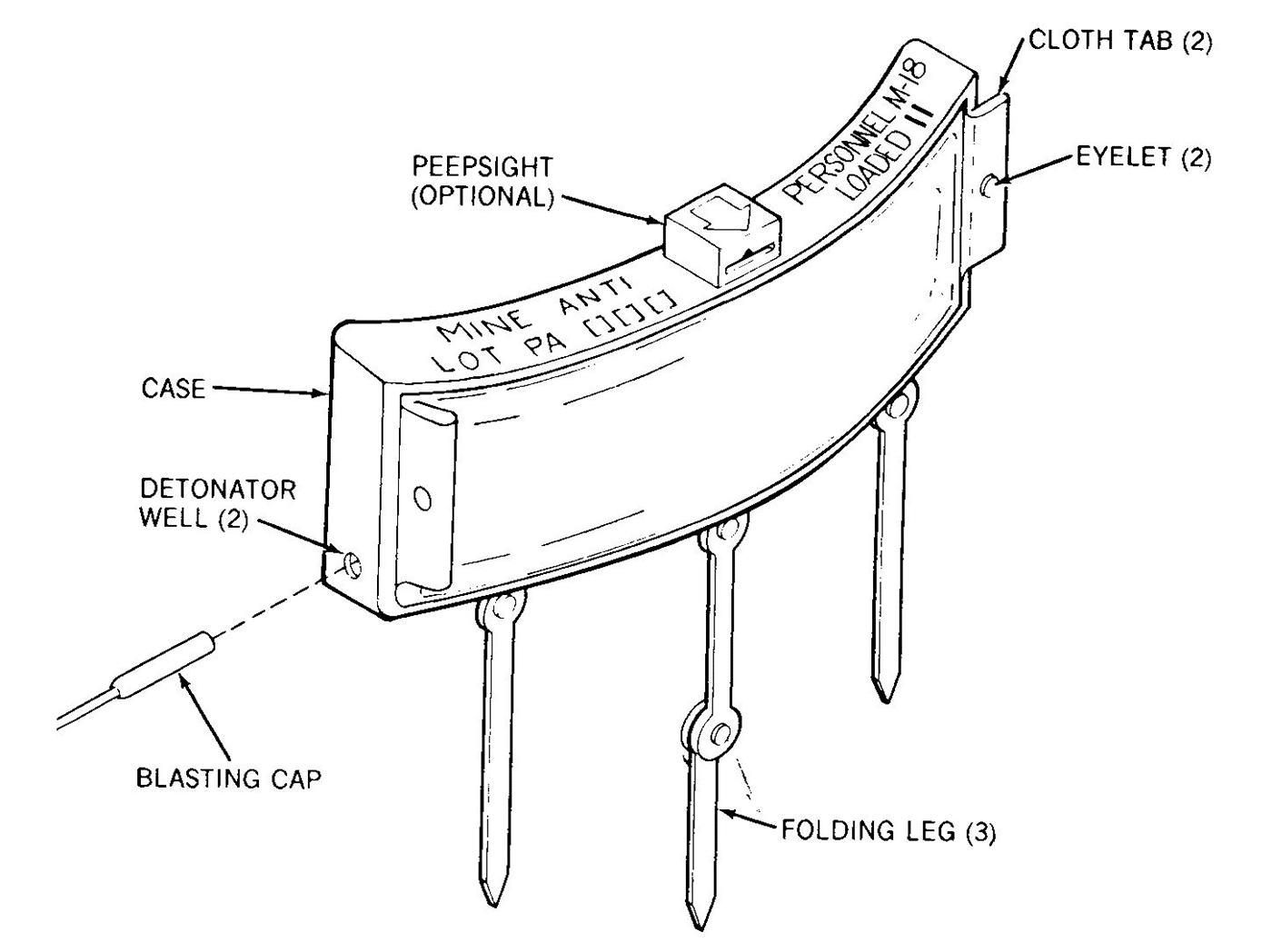

The M18A1 Claymore is essentially a plastic casing, slightly convex in shape, which contains a pound and a half of C4 explosive. Embedded in the C4 are 700 one-eighth-inch steel ball bearings, which make up the shrapnel that is discharged when the mine is detonated. Those ball bearings are approximately the size of a .22 round and are blown out in a 60-degree arc to the front of the mine when it’s triggered. That arc runs from two meters high to 50 meters wide. It’s lethal at about 50 meters and anyone out to about a hundred meters is likely to become a casualty.

In simple terms, to set the Claymore a soldier or Marine selected a firing position that would give him some protection from backblast, about 20 meters to the rear of the mine itself, and preferably in a hole or behind solid frag cover.

At that point, haul the package to the selected emplacement site, keeping the firing device safely under control in a pocket. Set the mine by unfolding four pointed legs, two on each end of the mine, and press it firmly into the ground. Go prone and aim the device along the intended path of devastation using the peep-sight provided atop the mine casing.

Then, pull the shipping plug from one of the two “ears” on top of the device and thread in the blasting cap. Screw the shipping plug back in to prevent the wired cap from dislodging and camouflage the emplacement with local flora. Then unspool the wire as you return to the firing position.

At that point, connect the firing device, set the safety bail on the clacker and hang out waiting for the bad guys to approach. Some units had different SOPs for emplacing Claymores, but that’s basically the method involved with getting the mine emplaced, armed and ready for action.

Brutal Simplicity

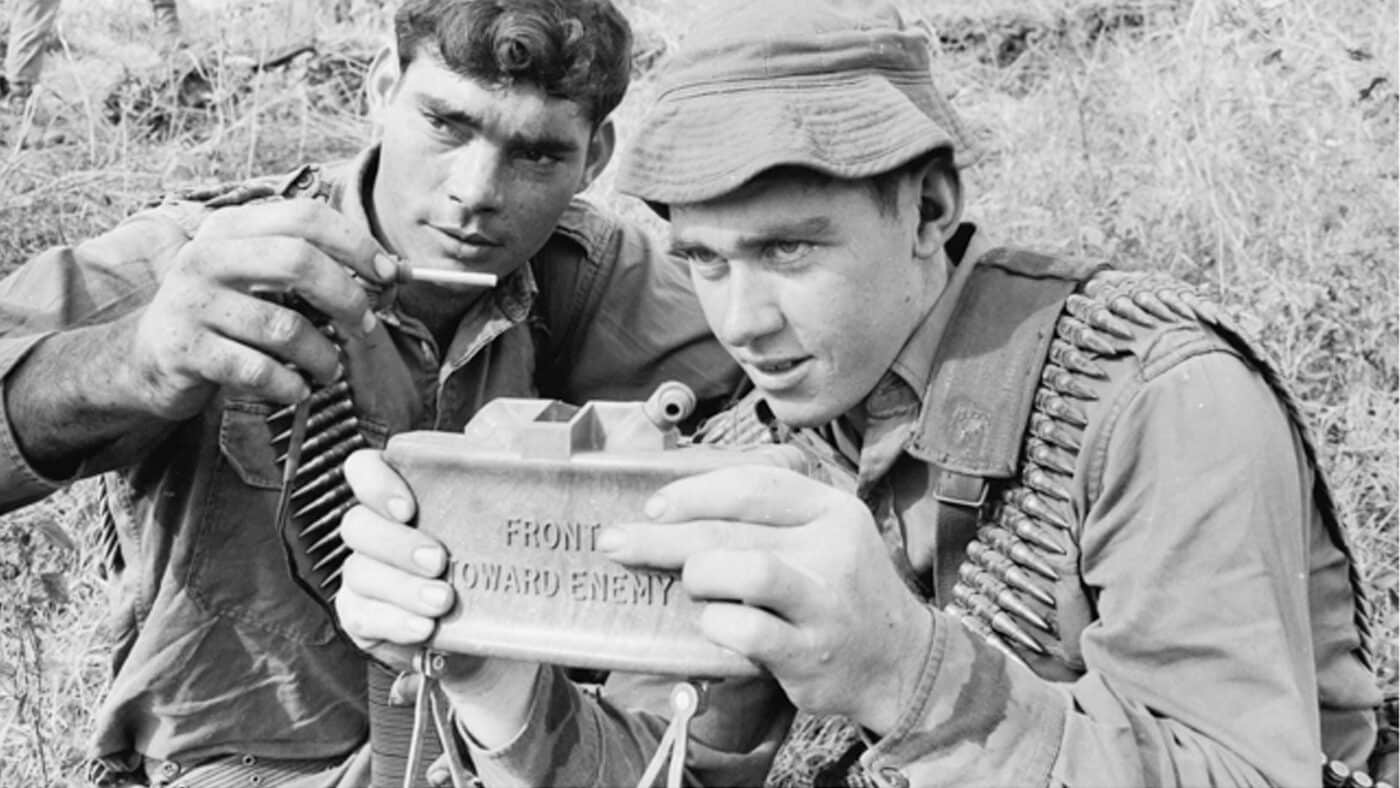

A Claymore has the words FRONT TOWARD ENEMY embossed in raised letters on the business side of the casing, which made it fairly dumb-ass proof. When it was necessary to emplace a Claymore at night, you could reassure yourself by braille that you had the thing pointed in the intended direction.

This brings up the stories from Vietnam days about VC or NVA sappers crawling silently up to a Claymore position and simply turning the mine around so it would fire back on the unit that set it in place. While I never actually saw that happen, I’ve heard enough tales about it from other veterans to believe there must be something to the claims. And it seems to me that a unit that set up its Claymores during daylight hours or in plain site or nearby villagers who just might be rice farmers by day and radical guerillas by night, could suffer the consequences of a reversed Claymore detonation.

On the Other Side

Not that the enemy in Vietnam didn’t have plenty of their own lethal toys to cause Allied nightmares. They most certainly did as casualties from high-explosive mines and boobytraps can attest.

The VC/NVA did employ their own version of a Claymore. Officially the Dh-10 directional mine, it looked something like a large lollipop on a swiveling wood or metal frame, which was used to direct the blast. It was employed in much the same way as our version and was packed with the same lethal shrapnel to prevent movement along jungle trails.

Later versions of ChiCom Claymores included a Type 66, which was a direct rip-off of our M18A1 down to the same function, shape and appearance — including raised print on the front in Chinese characters.

Conclusion

Few anti-personal mines have proved as successful in combat as the Claymore type. Practically every nation with a standing military force has one or has access to something like it through allies. And our own R&D components have continued to update and improve the M18A1.

The more modern version of the weapon includes a non-electric firing device featuring a shock-tube and pull-initiator that saves some weight and increases the methods for firing the device — specifically, rigged as a hands-free explosive that detonates when disturbed by the enemy. And there’s a mini-mine version available to some modern line units of Special Forces teams called the Mini-Multi-Purpose Infantry Munition that is employed in much the same fashion as its larger cousin, but is smaller and weighs only about half as much.

Sidebar: Original M18 Claymore

The Claymore mine’s roots trace back to World War II. During that time Germany experimented with a “side attacking” anti-tank mine that used the same general principles as the Claymore. Additionally, the country looked at using the technology against infantry as a “tench mine.”

After experiencing the overwhelming numbers of troops brought to the battlefield by the Chinese in the Korean War, Canada developed the Phoenix landmine that used the same principles. It was thought that a directional mine with a fan-shaped pattern might be able to disrupt human wave attacks. With Composition B as the explosive, the Phoenix mine would launch a curtain of steel cubes toward an enemy. The range was relatively short — maybe 30 meters on the outside — and it was too large to be man-portable.

In the U.S., Norman MacLeod developed the T-48 mine for the Picatinny Arsenal. The T-48 was a directional mine that used cube-shaped steel projectiles like the Phoenix. Also like the Phoenix, it had a limited range: less than 30 meters. However, it had a huge advantage over the Canadian mine: it was infantry-portable.

Unlike the M18A1, the first Claymore mines used a battery to trigger the detonator.

Approximately 10,000 of the original M18 Claymores were manufactured, and some were used in the early days of the Vietnam War.

The Picatinny Arsenal issued a request for proposal in 1954 for an improvement to the original M18. As a result, several design changes were tested and adopted. One of the most significant was that the projectiles changed from a cube shape to a spherical one.

Initially, the new projectiles were 7/32″ ball bearings made of hardened alloy steel. Testing showed that these balls broke apart when the explosive detonated, diminishing both the range and lethality of the mine in the target area.

Engineers opted for smaller 1/8″ steel balls that were relatively softer. The result was a more efficient and deadly directional anti-personnel mine with an effective range up to 100 meters. Within a range of 55 yards (50 meters,) the updated mine would hit about 30% of the enemy. With small changes, this new variant was standardized as the M18A1 Claymore anti-personnel mine.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

859

859