M3 Grease Gun: Taking a Cheap Shot

January 26th, 2021

9 minute read

Around the 1920s, first-generation submachine gun designs featured finely machined metal and wood stocks. While these weapons were growing in popularity with troops around the world, government accountants often passed them over as “too expensive.” The demand for full-auto firepower was high, but budgets were tight. Consequently, arms makers often sold their designs in small lots, but rarely with a contract to become widely issued, standard equipment.

When World War II and the Blitzkrieg-era arrived, the German’s all-metal, folding stock submachine guns (the MP38 and MP40) quickly created quite a stir with their innovative design. The Allies found themselves scrambling to come up with their own lighter and more cost-effective submachine guns. (Read more about the submachine guns of World War II.)

Is Less, More?

Beginning in 1941, Britain produced the Sten Gun, an innovative, indigenous submachine gun design. The Sten was lightweight (a little more than 7 lbs.), simple to use, and exceptionally cheap to manufacture (less than $10 each). While the Sten was effective enough in combat, its outrageous cheapness didn’t endear it to British and Commonwealth troops. However, the gun was widely considered to be a success.

The cost-effectiveness of the Sten was not lost on American arms designers who looked to replicate the success of that firearm with a design of their own. The U.S. Military had adopted the Thompson submachine gun during 1938, but when war came to America in December 1941, the “Tommy Gun” was only available in small numbers to American troops. America had also provided the Thompson in some quantity to the British, who found themselves without a submachine gun at the beginning of the war.

While the Thompson gun was carefully crafted in its manufacture, it had two primary drawbacks. First, it was rather heavy — the Model 1928 was a hefty 10.8 lbs., unloaded. The second drawback was strategic in nature — the Thompson was extremely expensive to produce.

Before the war, a single Thompson gun cost the U.S. government as much as $209. As design changes were instituted (creating the simplified M1 version), individual gun costs were brought down to $70. The further simplified M1A1 brought down the price per gun to $45 apiece. The time and cost it took to manufacture it, coupled with the strategic materials required to build the Thompson, added up to an unsustainable solution that was considered too taxing on the American war effort.

Greasing the Gears of War

Colonel Renee Studler of U.S. Army Ordnance was given the task of developing a submachine gun with a focus on ease of use and simplicity as well as cost-effectiveness in manufacturing. Colonel Studler put together a design team consisting of George Hyde and Frederick Sampson. Mr. Hyde was a noted arms design engineer, while Mr. Sampson (of the Guide Lamp Division of General Motors) was an expert in the field of stamped metal construction.

As it turns out, this was a perfect combination to create what would become the M3 submachine gun. Using readily available and non-critical materials, they developed a revolutionary new design in American firearms manufacturing. This design could be subcontracted out to machine shops around the country for rapid production.

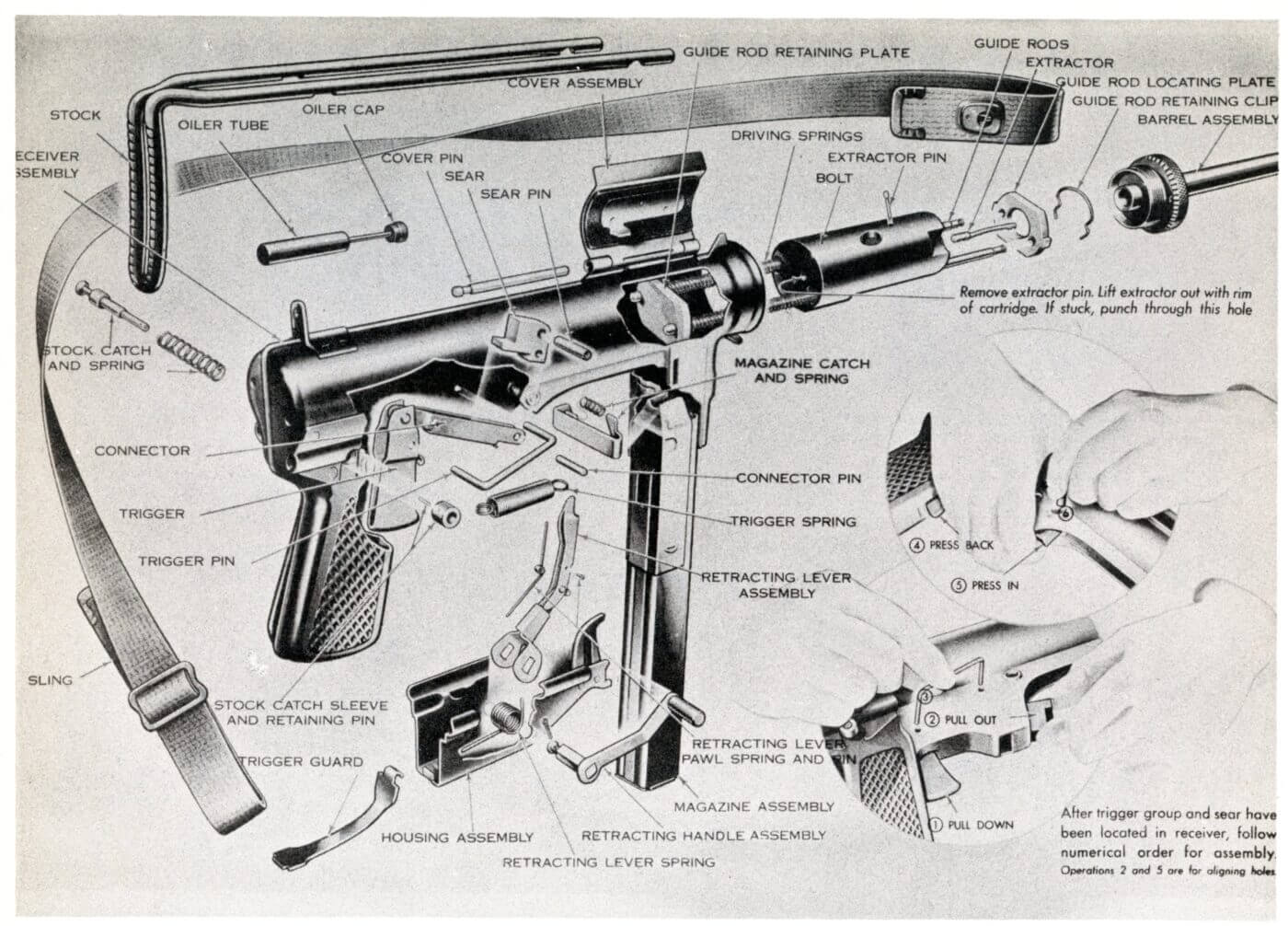

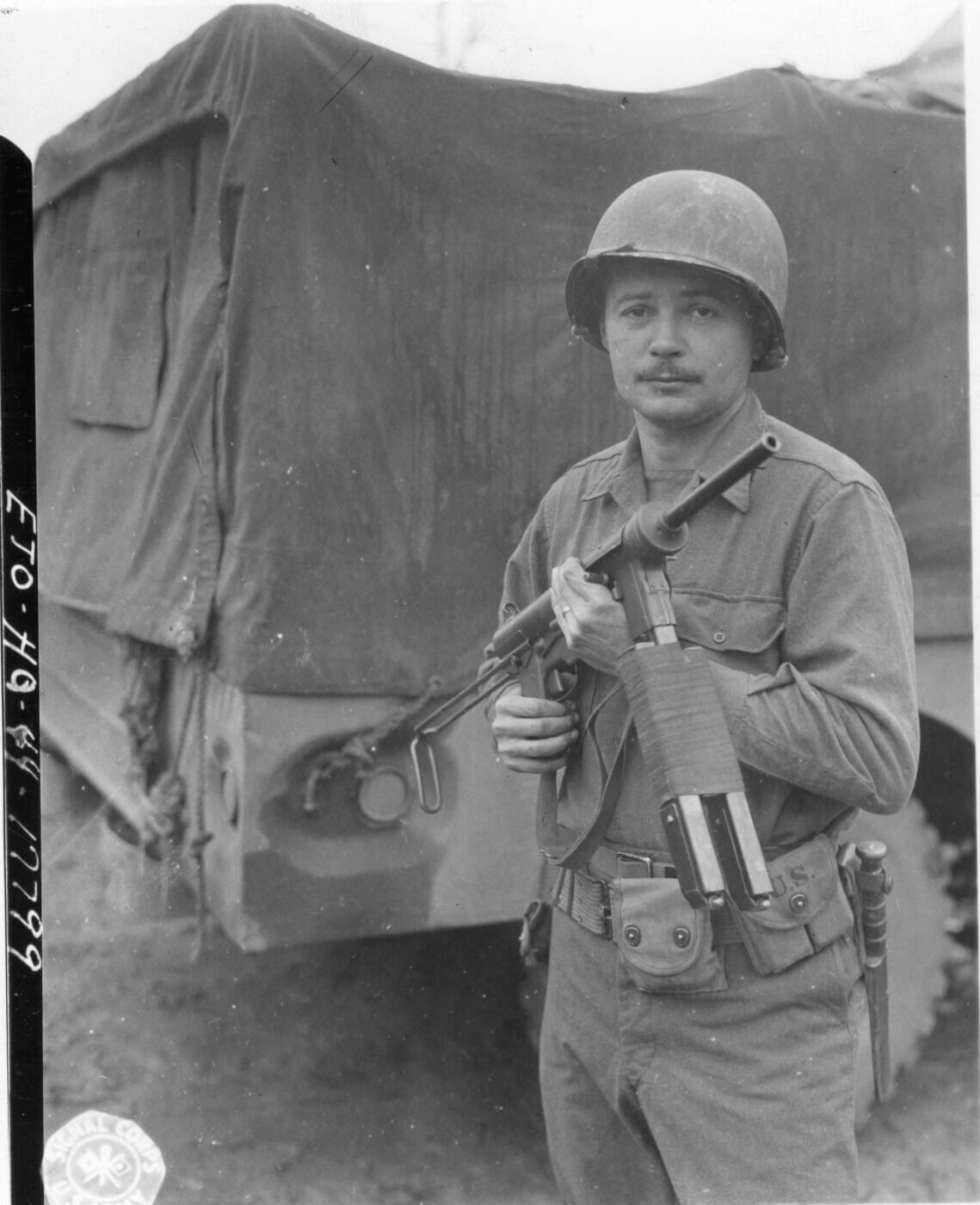

Ultimately the M3 was the first primary American firearm to use stamped and pressed metal in its design, along with spot welding. Ingenious features included a telescoping wire frame buttstock that was threaded on the ends to accept a bore brush — allowing it to double as a cleaning rod. The M3 quickly earned the nickname “Grease Gun” for its resemblance to the mechanic’s tool and its overall workmanlike appearance.

Designated as the US Submachine Gun, Cal .45, M3, the new submachine gun was accepted into U.S. Army service on December 12, 1942, although it would be some time before the “Grease Gun” would see combat. Throughout 1942, the guns went through a rigorous series of evaluations, and when approved for production, GM’s Guide Lamp Division produced more than 600,000 M3 submachine guns by the end of World War II.

The Details

The M3 is a blowback weapon that fires from an open bolt in full-auto only. However, the low rate of fire (about 450 rounds per minute) makes the gun quite controllable, and most shooters can easily squeeze single shots out of it. An excellent design feature of the M3 was the use of dual operating rods and springs, which could be adjusted so that the bolt never “bottomed out”. The heavy bolt was carefully engineered so that it never struck the back of the tubular receiver.

The stamping for the receiver created a solid pistol grip, complete with pressed-in serrations, offering a truly “man sized” submachine gun. The M3 is strongly built, and the whole receiver is welded together with a threaded insert for the barrel coupled by a sturdy collar.

Initial issues with the ejection port were corrected and this created a simple, but robust safety. When the ejection port cover is open, then the weapon is ready to fire. When the cover is closed, the weapon is on safe, as the cover cleverly moves the bolt off the sear. It is nearly foolproof, and one of the finest safeties ever employed on a military weapon in my opinion.

The M3 had two flaws that were corrected in the later M3A1. The original design’s cocking handle was complicated and fragile, and prone to breaking. Second, disassembly was complicated in that the trigger and cocking mechanism had to be removed before the bolt assembly could be taken out.

The M3A1 was not adopted until December 1944, so very few made it into combat by the end of the war. The improvements in the M3A1 were straightforward. First, the exterior cocking mechanism was replaced by a “finger hole” drilled directly into the lengthened ejection port so the bolt could be retracted by the user’s hand. The bolt was also improved so that the ejector went through the bolt, allowing the whole assembly to drop out in one piece by simply unscrewing the barrel assembly. Finally, the wire shoulder stock was also modified to include a magazine loader, and the stock was bent to allow it to be used as a wrench to loosen the barrel nut assembly. Plastic caps were also issued to keep loaded magazines clean until they were ready for use.

The M3 proved to be a robust and reliable weapon. The advances made in simplified production created a very cost-effective weapon system as well, as each “Grease Gun” was estimated to cost just a little over $20. Due to its low production cost, the M3 was originally intended as a “disposable” weapon, and troops were to throw it away when it wore out.

However, this did not prove practical in combat. After D-Day in June 1944, the limited supply of M3 submachine guns forced U.S. Army Ordnance workshops to fabricate various spare parts (which had never been created at the factory as part of the original low-cost concept of the M3) to keep the issued Grease Guns in operation. In action, when replacement parts for the M3’s cocking handle were unavailable, some guns were field modified to include a protruding cocking handle attached to the bolt, and a slot cut into the top cover to accommodate it.

M3 Experimentation

One seldom-mentioned M3 variation was the T29. Submitted in the fall of 1944, the T29 was an attempt to chamber the M3 for the .30 M1 Carbine round. Only three were made as it was found that the .30 Carbine load was a bit too much for the M3’s spring action. With plentiful M1 Carbines already in service, and with an upgrade soon coming to provide the Carbine with selective-fire capability, the project was soon dropped.

Attempts were made to provide a “curved barrel” for the M3 submachine guns, intended for use by tank crews. This would enable the tankers, firing from hatches and loading ports, to shoot at enemy anti-tank teams that lurked in the blind spots of the vehicle. A few examples were made and tested, but interest in the idea quickly faded after World War II and the concept of bent-barrel M3’s was abandoned. During World War II, Germany also made efforts to develop curved-barrel rifles.

Approximately 25,000 M3s were designated for use with the American OSS (the precursor to the CIA) and were delivered by early 1945. The OSS guns were chambered for the 9mm Parabellum round and were quickly adapted to this caliber by replacing the M3’s barrel and bolt, and inserting an adapter that allowed the use of British Sten gun magazines.

Bell Labs also designed an integral suppressor for the M3, as this was also requested by the OSS. These weapons were intended for use by OSS agents in their covert operations. These guns were also were under consideration to be supplied to various resistance groups in Europe and Asia. (See what might possibly be one of these OSS suppressed M3 submachine guns found in the Philippines.)

Soldiering On

The M3 continued in U.S. service through the Korean War and well into the Vietnam War. Meanwhile, it seemed that U.S. Ordnance was always looking for a replacement to the submachine gun concept, but that answer was not easily found.

The M14 rifle was tried, fitted out with a pistol grip and a folding stock. The M16 rifle was modified into the SMG-like CAR-15 XM177 (to learn more about the XM177, click here). Despite these efforts, nothing fit the bill — particularly for armored vehicle crews — like a true submachine gun. Consequently, M3A1s could still be found in the weapon racks of U.S. armored vehicles even into the mid-1990s.

In his 1945 edition of Small Arms of the World W.H.B Smith described the M3 SMG:

“This weapon was developed by our Ordnance Department to fill the need for a submachine gun low in cost and simple to manufacture. It is the United States’ answer to the British Sten gun and the German machine pistol 38. It is crude in appearance, because its cost is less than that of a good automatic pistol.”

America had never produced such a utilitarian firearm before, and initially many troops had little faith in it. But necessity is the mother of invention, and the development of the Grease Gun gave U.S. troops a reliable submachine gun that served in multiple wars. Designed to be mass-produced at very low cost, the M3 Grease Gun went on to provide an incredible long-term return on investment.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

264

264