The Noble

(but Doomed) M551 Sheridan in Vietnam

April 29th, 2023

8 minute read

The M551 Sheridan Light Tank, an ambitious project designed to deliver powerful armored support to U.S. troops, ultimately fell short of its potential due to various design and operational issues. The tank, characterized by its sleek appearance, flexible mobility and high speed, could support paratrooper operations due, in part, to its lightweight aluminum alloy construction. Despite its impressive firepower, the Sheridan faced significant challenges, including a finicky track system, sensitive ammunition, and vulnerability to anti-tank weaponry. In this article, Capt. Dale Dye, U.S.M.C. (ret.) recounts the noble, but ultimately doomed, journey of the M551 Sheridan Light Tank, offering a glimpse into its potential, drawbacks, and the harsh reality of warfare.

As a result of losing a urination competition with a senior officer over assignments in the summer of ’69, I found myself homeless in Vietnam. As a sore loser in a towering snit, I did something a salty Marine sergeant should never do. I volunteered myself for assignment to any combat outfit that needed a warm body.

Through a confluence of events too weird to recount, I wound up temporarily assigned to a U.S. Army advisory team mentoring the 4th ARVN Armored Cavalry Regiment in northern II Corps. It would have been a fairly sweet deal if I knew anything about armor, which I didn’t. But the soldier advisors were happy to teach me.

One of my first lessons was that armored vehicles require regular maintenance, which means pre-op, post-op and all the time in between. Nothing on or about a big, motorized steel box on tracks is in any way lightweight. Everything you touch wants to chew your knuckles, crush your fingers or cause arterial bleeding. And there are few things on a track or tank that weight less than a ball-busting ton or better.

Apparently, tankers are great believers in the Archimedes Principle, and leverage is applied to balky components with hernia-inducing wrenches or prybars long enough to move the earth. Looking back beyond the pain, bruised knees and damaged ego, I recall most of it fondly.

Lighting the Way

After learning to salute indoors and shape a black beret so it didn’t look like I was wearing a pizza plate on my head, we got down to the cool stuff by reviewing the unit’s armory. The infantry troopers — called dismounts for some arcane reason — were hauled into the fight via the Army’s bog-standard Armored Personnel Carrier, the M113.

Unlike the Marine amphibian tractor version of an APC (35-plus tons), the speedy little Army version weighed in at a spare 12-plus tons due to its mostly aluminum alloy construction. It was powerful enough — pushed by a 275hp Detroit Diesel — to bull bush and deliver troops to the fight even in fairly heavy jungle terrain. The APC was rated roomy enough to carry up to 15 dismounts, but we were dealing with diminutive South Vietnamese soldiers here, so the personnel payload was up around 20 men or more if the advisors could shoehorn them aboard.

And the M113 was not just an armored truck. The Army developed a version called the ACAV (Armored Cavalry Assault Vehicle) that looked something like a pissed-off porcupine with multiple machine guns mounted and pointing in all directions.

An ACAV kit for the M113 included armor gun shields and a fully rotating turret ring for the M2 Browning .50 caliber in the Track Commander (TC) position. There was also provision for two M60 machine guns with shields for gunners covering the left and right rear of the vehicle. To help with surviving AT mine encounters, which were a constant threat in our AO, the improvements also included a bolt-on belly armor kit.

As an armor neophyte, I mostly manned one or another of the machine guns until the day deep in a muddy patch of jungle when our ACAV driver made an overly abrupt turn and threw a track. It was at that point I realized there was more to being an armor crewman than looking cool in the turret, breaking stuff and killing people. By rough calculation, I dug about 37 foxholes worth of mud and putrid mulch just to get at the errant track that was buried atop a colony of stinging ants.

Stepping Up

Shortly thereafter I made a pitch to broaden my knowledge of armor in other areas, and the CO turned me loose to learn something about the unit’s big hammer. To support armored infantry tactics in our area, the 4th ARVN Armored Cav had a tank…sort of.

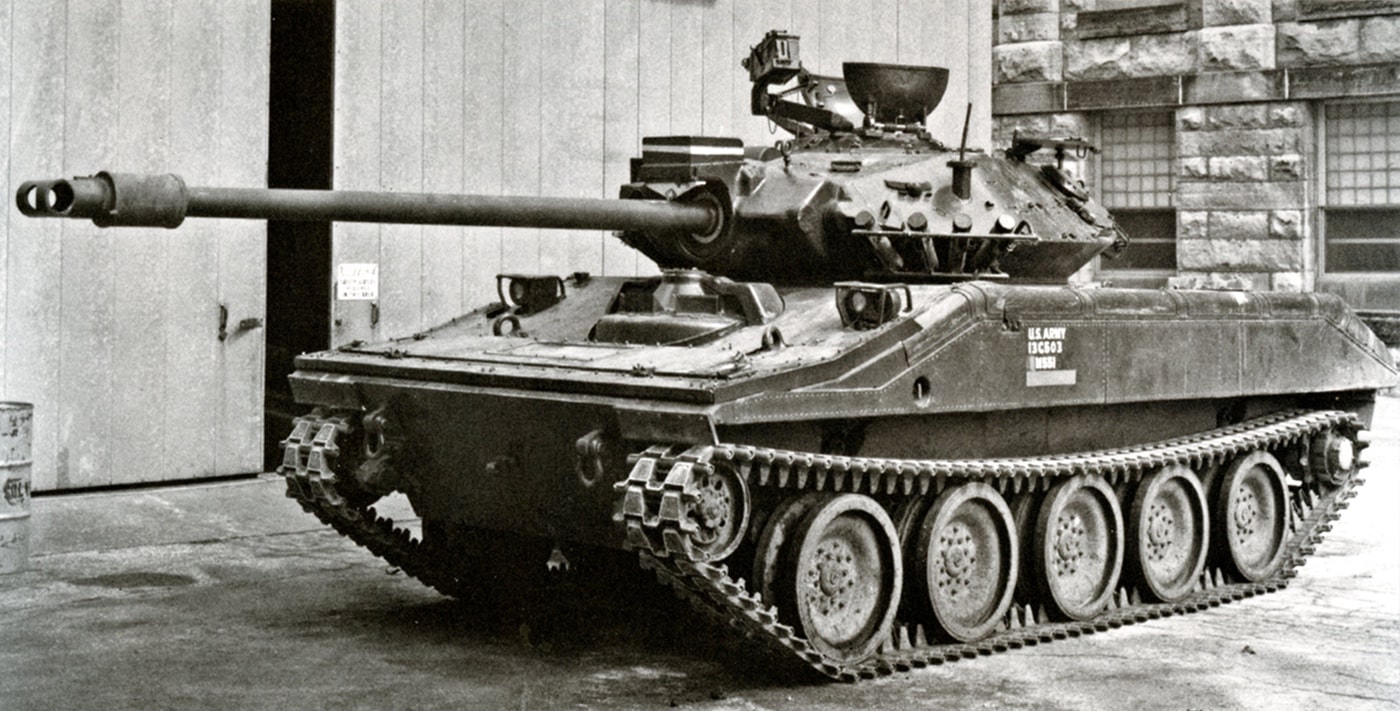

It was the relatively new M551 Sheridan which had only just arrived in Vietnam at the first of the year (1969). It was a hotrod by armor standards, powered by a supercharged six-cylinder Detroit Diesel and capable of around 50 mph on a flat surface with a tailwind.

The Sheridan was sleek and had a futuristic look with a cool saucer-shaped turret mounted on a vehicle that weighed in at just 16-plus tons. It seemed most things in the Army’s vehicle inventory in those days had to be light enough to drop along with paratroopers in airborne operations. None of the advisors in our outfit had ever seen a Sheridan dropped by parachute. As veteran tankers, most were dubious about what a paradrop would have done to a Sheridan’s aluminum armor or delicate fire-control equipment.

That equipment on a Sheridan was delicate mainly because it was designed to aim, fire and guide a missile — the MGM-51 Shillelagh missile bunker-buster — via an infrared sighting system. Non-missile ammo for the main gun — a 152mm smoothbore capable of firing HE, AT and canister — was sort of an afterthought.

The missile drill was way too complex as well as relatively useless in Vietnam combat conditions, so the Sheridans arrived in Vietnam sans Shillelaghs. As it turned out, when the sewage struck the propellors, the Sheridans that could be nursed out of maintenance and into combat did fairly well, especially against enemy bunker complexes and other hard points.

Where It Counts

The infantry loved the Sheridan’s M265 canister round, an updated version of the venerable battlefield favorite Beehive. The Sheridan’s canister rounds were the money shots in Vietnam.

Thin skin and a finicky track system with no support rollers were drawbacks, but the vehicle made up for some of that with road-speed and firepower. But there were some serious kinks in the firepower department that had to be addressed.

It was generally either hot and humid in Vietnam or chilly and wet. Neither condition was good for the Sheridan’s best ammo load — the caseless M265 canister round as it was initially delivered along with the Sheridans.

Crews rapidly discovered that humidity played hell with the combustible cartridge cases, making them almost as much a danger to the crews as to an enemy. Cartridges that were meant to detonate in the breech too often did so in the turret. Blazer messages were launched from the battlefield and landed on the appropriate desk at Aberdeen, which responded with special ammunition covers that had to be removed before firing. It was a little safer for the crew but still painfully slow.

Where an M48A3 main battle tank crew could fire the 90mm as fast as the loader could shove rounds into the breech, the poor Sheridan loader dealing with caseless ammo and a missile-designed system could likely only put a pair of rounds downrange.

Like its M48 Patton tank big brother, the Sheridan had fairly standard secondary armament. There was a .30-caliber co-ax mounted beside the tube and an M2 .50-caliber in a sky-mount on the turret roof. About 4,000 rounds of machinegun ammo were carried into combat. Unfortunately, all of it had to be stowed outside the tank since room in the turret was at a tight minimum. Reloads after firing all the ready MG rounds was a dangerous donkey drill under fire.

Conclusion

In the end, the M551 Sheridan had to be called a failure in Vietnam combat operations. Given fairly constant mechanical or electronics problems, fire (and firing) hazards, plus a lightweight chassis that got eaten for lunch by AT mines and the ubiquitous B-40 and later RPG-7 AT rockets that proliferated among NVA units late in the war, the Sheridan was way too often a combat casualty. And those casualties were most often both the vehicle and the entire four-man crew.

By the time of the Cambodian and Laotian border operations in 1970-71, even the Sheridan’s biggest fans were ready to call the game as lost. Only some 200 of the vehicles ever made it to the war zone. It was a noble but ultimately doomed experiment during the Vietnam War that showed high-tech won’t always tip combat odds in your favor.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

199

199