Medieval WWI Trench Weapons

October 18th, 2022

11 minute read

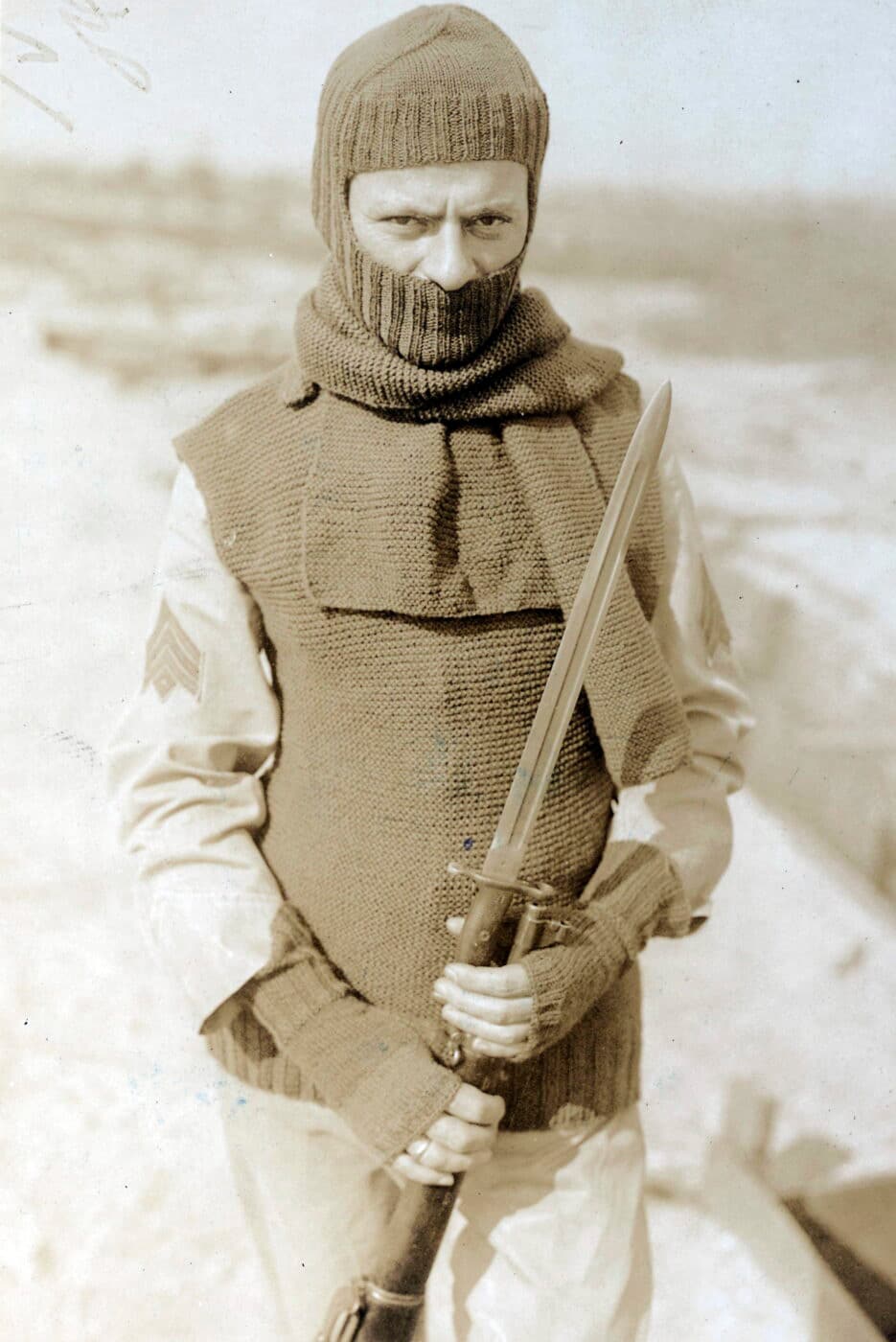

From trench maces to knuckle dusters, the truly medieval weapons employed by trench raiders in World War I were employed in some of the most brutal combat seen in the 20th century. In today’s article, Tom Laemlein looks at these trench weapons.

Almost any time World War I is mentioned, the term “trench warfare” inevitably comes up. Most of those trench warfare references are about the overall condition of the Western Front, particularly the massive battles of 1916-1917, when thousands of men lost their lives in pointless assaults that achieved little more than mass slaughter.

By the spring of 1918, American troops were arriving in France at a rate of more than 5,000 per day. The Doughboys had to learn the difficult and very specific lessons of trench fighting. Even though the French and British provided experienced instructors and training manuals to the newest Allied nation, American troops still brought their own special weapons and unique fighting spirit to the brutal business of trench raids.

“Boys, I’m Dying”

Private Dyer J. Bird of the US 42nd Division, 166th Infantry Regiment, was recently deployed to France in 1918 and was stationed at a listening post. He saw a large German raiding party emerge from nearby shell holes and rush toward the American trenches with weapons in hand. The young Doughboy hurled two hand grenades into their midst and when he turned to call out and warn his comrades he was shot through the chest.

“The Germans are coming in the form of a wedge. Boys, I’m dying.” Dyer’s warning gave his unit enough time to turn back the German raiders. It was part of the hellish introduction to trench warfare that fresh American troops received in early 1918.

In “The Doughboys” (Harper & Row, 1963), Laurence Stallings described the style of training that the young Americans received from their French allies, the Poilus worn down physically and emotionally from 3½ years of bitter fighting.

A Doughboy had to learn the formal trench warfare of the French, with emphasis upon Chauchat and Hotchkiss guns, bayonet and grenade, barbed wire, and the shovel—and little attention to the rifle. Frenchmen pursued Germans in a clash of patrols by throwing grenades at them, as if the Lebel rifle possessed no trigger assembly.

If Intelligence desired a raid, with a prisoner brought back for interrogation, it was understandable but deplorable. Some friend might be killed by grenade or bayonet, and a wounded enemy dragged back through the gaps in the barbed wire.

The Doughboys (Harper & Row, 1963)

What the Doughboys lacked in experience in the conduct of trench warfare, they made up for in aggressiveness. The British and French commanders craved the American zeal for combat, while the Germans massed on the other side of the lines, first mocked it, and later feared it.

Some of the first prisoners taken by the Americans said things like: “If only we could have met you in 1915 when we too were young!” Stallings recounts the Doughboys’ eagerness to fight: “Each man in the 1st Division wanted to go on a patrol, and then a raid, each wanted to kill a German, to capture one, to be the first.”

The trench raid was a nasty, brutal business, conducted almost exclusively at night. Raiders reduced their equipment to the essentials of rapid movement and close-quarter killing power, often with specialized trench weapons. Trench raids were tactical reconnaissance in their most aggressive form — quick strikes designed to assess enemy strengths and activity, to cause as much mayhem as possible within enemy lines, and to grab a handful of prisoners and drag them back for interrogation.

The following description of an American trench raid is from a cable sent by General Pershing’s AEF headquarters to the War Office in Washington DC on June 13, 1918.

Our raiding party consisted of five groups, each under the command of an officer. The raid was executed in the Bois Allonge, the raiding party entering from the west and penetrating to the eastern edge. The first party moving in a northwesterly direction located a lighted and occupied dugout.

On the occupants’ refusal to come out, it was destroyed by the use of phosphorus and other grenades. The second party encountered fire from an automatic rifle as they entered the woods. The gun was rushed, three of the gun crew killed, and the gun captured.

The party then moved to the eastern edge of the wood where three men were found in a light shelter. One was killed and the others taken prisoner. The third party was also fired on by a machine gun. This gun was rushed and its crew killed but as the gun was chained to a tree it could not be brought back. The fourth party encountered a group of the enemy and opened fire with rifles. Four of the enemy were seen to fall.

The fifth party reached the eastern edge of the woods and then moved along the edge in a southerly direction. Several shelters and dugouts were located and destroyed by incendiary bombs. It withdrew on the signal of the raid commander who ordered the retirement as soon as he assured himself that prisoners had been captured.

As a result of the raid much information was gained concerning the enemy’s defensive works, which include quarries and connected shell holes in addition to the trenches.

Cable from Gen. Pershing to the U.S. War Department, June 13 1918

An earlier cable from Pershing’s HQ gave a description of a typical German raiding party: “Their objective was to capture prisoners and gain information concerning our forces. Arrangements for the raid were shown in orders found on the body of a German officer in command of the raiding party. The attacking party consisted of the commissioned officer, three noncommissioned officers, and five squads taken from troops specially trained for such work. They moved in three sections. Support was furnished by artillery fire, four light trench mortars, four heavy machine guns, and three light machine guns. Of the latter, one MG furnished special protection for each section of the attacking party. Equipment of the attacking troops included eight stick grenades and four egg grenades on average per man. Double rations were carried.”

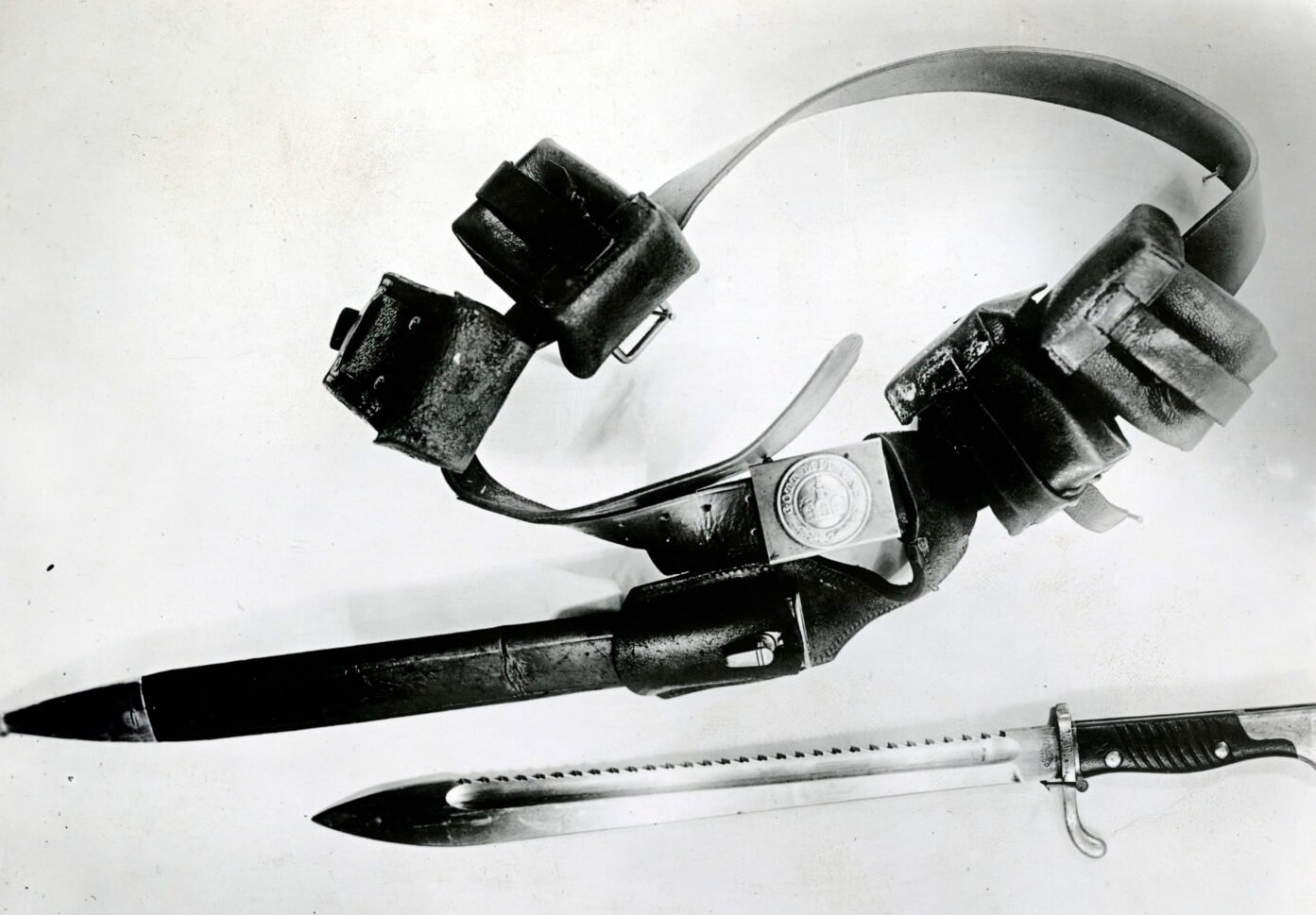

Laurence Stallings describes the preparations of a German raiding party in “The Doughboys”: “The Assault Company, swaggering among the holding troops, awaited its hour. Some among them took out pocket whetstones and sharpened trench knives, others looked to their Bangalore torpedoes for blasting barbed wire or blew sand from the stringed triggers of potato-masher grenades. Luger pistols were repeatedly cleaned and oiled, bayonet studs looked to.”

The Doughboys quickly learned the deadly game on the Western Front. From the city slickers to the country boys, Uncle Sam’s troops proved themselves to be fearsome fighters. American daytime patrols grew more frequent through the summer of 1918, and the nighttime trench raids more effective. By September, the great Allied offensive was ready to begin.

Weapons of the Trench Raiders

World War I saw the introduction of most of the modern weapons of war we have now become accustomed to, or horrified by — the armored vehicle, the submarine, the aircraft, the machine gun, the flamethrower and poison gas all saw their first significant use in World War I.

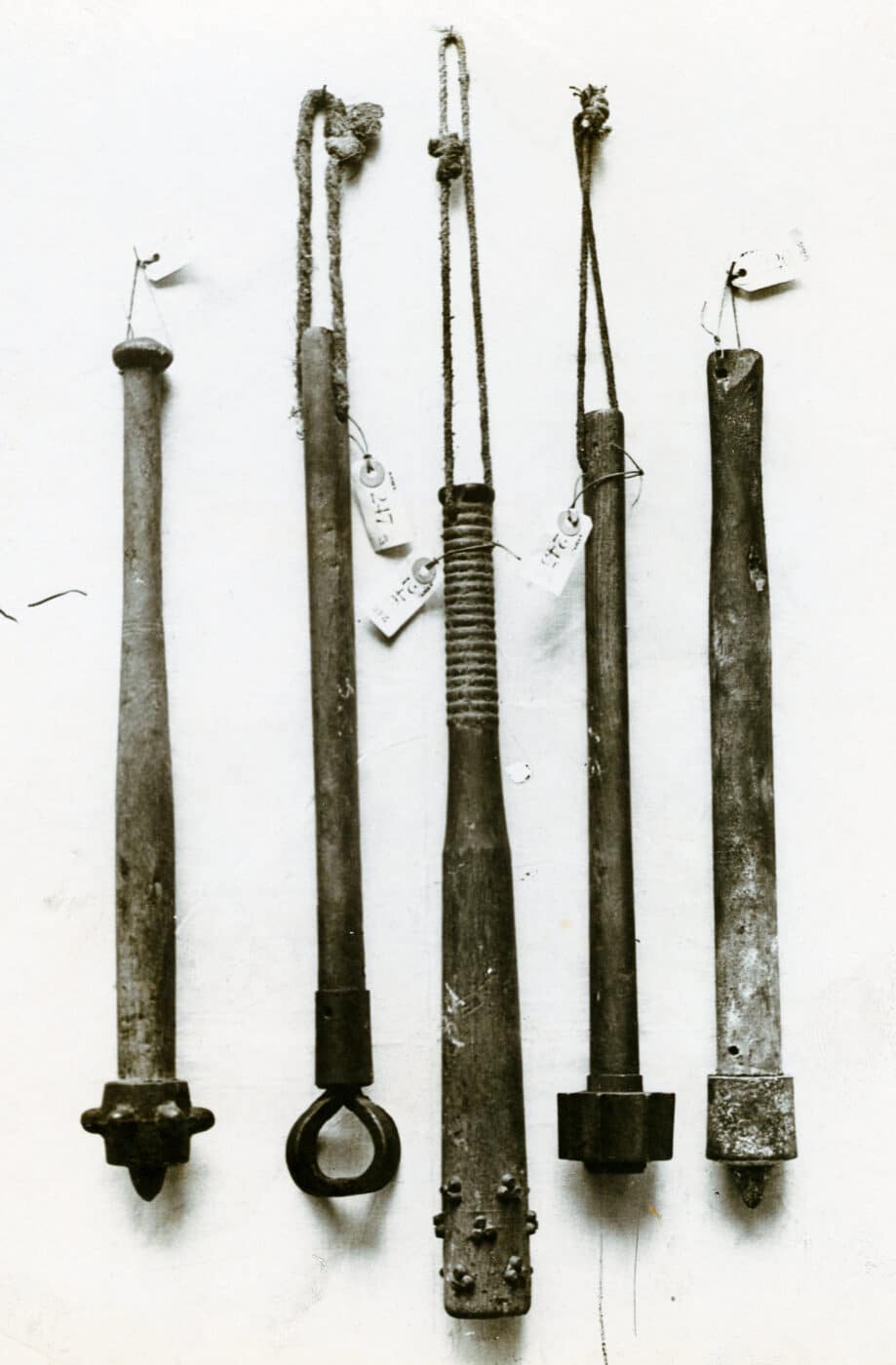

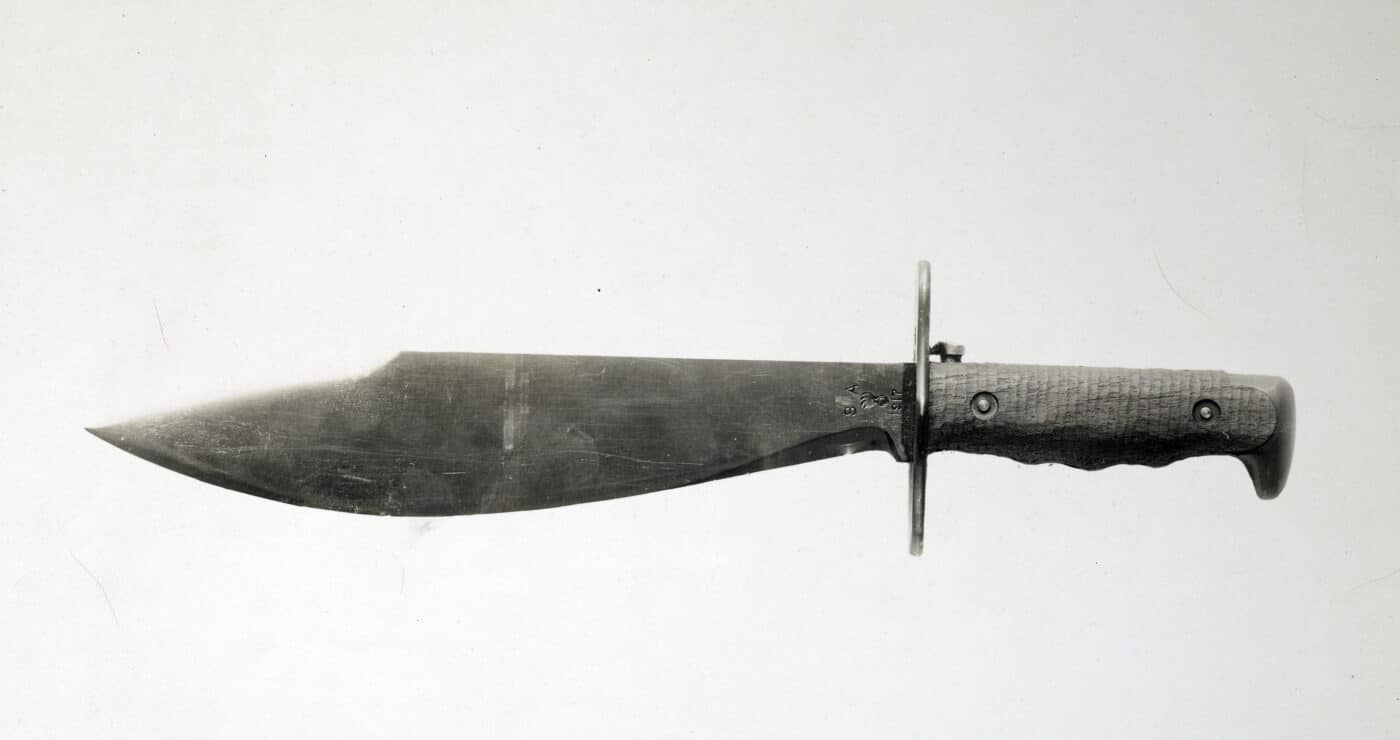

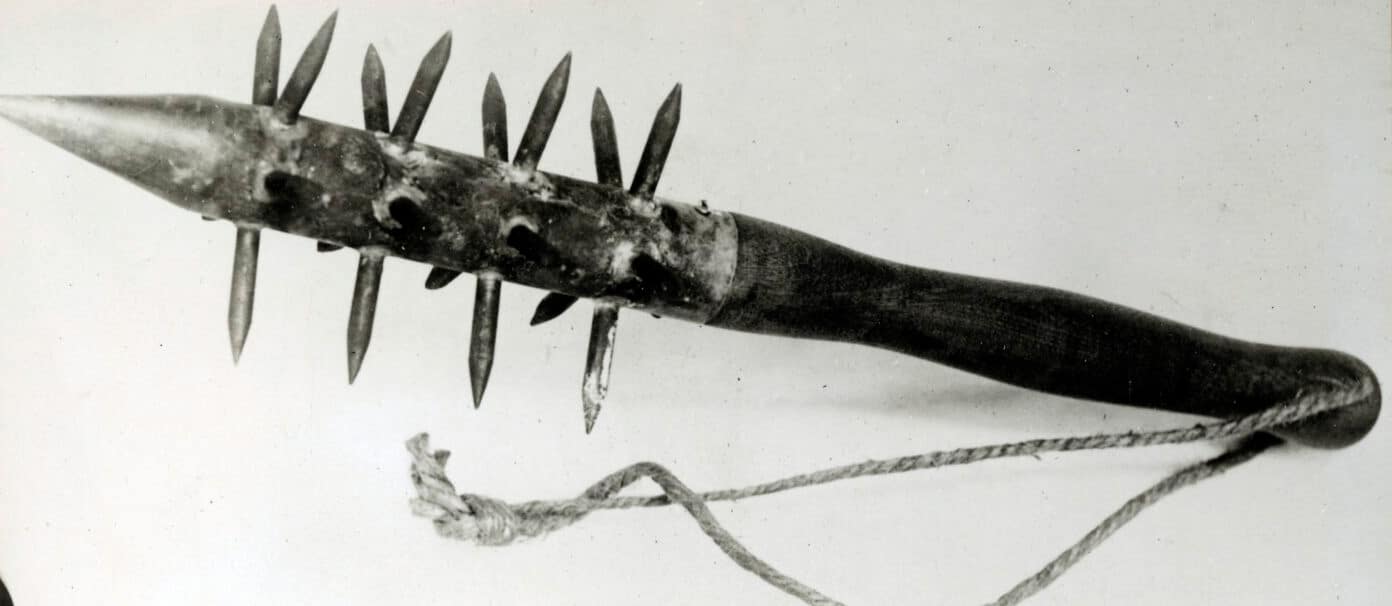

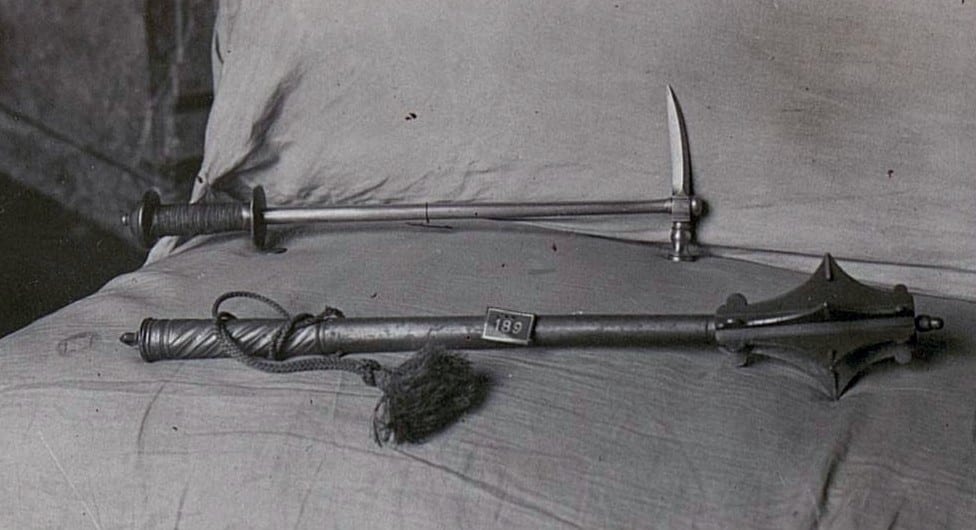

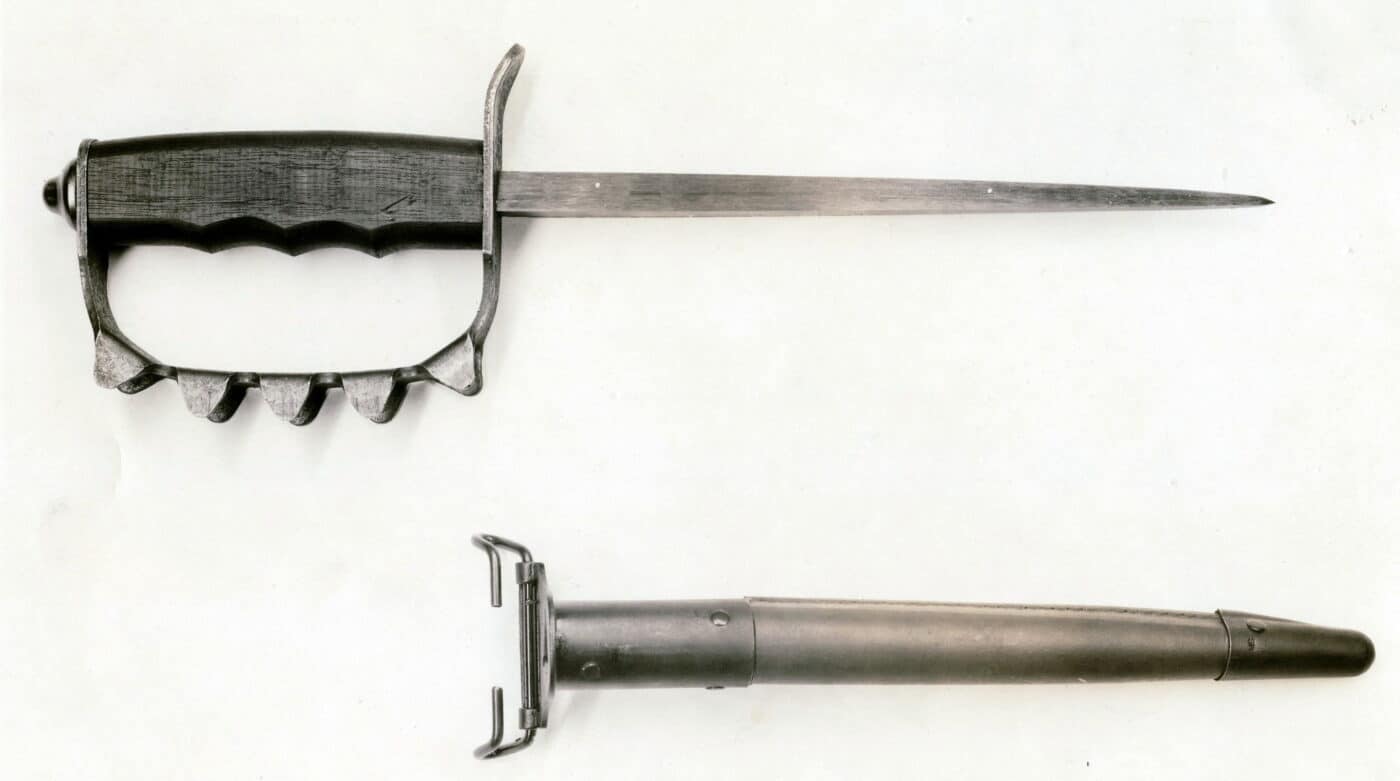

But just as war seemed at its most futuristic, the battles fought by the night patrols and the trench raiders reduced combat to its most primitive. Men hacked and slashed at each other with trench maces, clubs and sharpened entrenching shovels, deadly tools that seemed better suited for a medieval battlefield. Melee weapons included bayonets, fighting knives and daggers that were lightweight and silent killers. American forces had two specialized trench knives available to them.

M1917 Trench Knife

The M1917 was more of a pick than a true knife — using a triangular stiletto blade with a knuckleduster hand grip. The M1917 was designed to penetrate thick woolen uniforms and while the Doughboys often put it to good use, its stabbing-only blade was a bit of a liability.

Mark I Trench Knife

The American “knuckleduster knife” is a formidable-looking weapon that is a somewhat misunderstood design. The brass knuckle hand guard was meant more to help the soldier keep his grip on the knife in furious close combat. Even so, the opportunity to deliver a devastating punch to the face could make all the difference in a knife fight. The metal stub at the base of the pommel was called a “skull crusher”, adding yet another level of primeval violence to the weapon.

Few of the Mark I knives were finished in time to see action in WWI, but many were provided to American troops (particularly paratroops) during WWII.

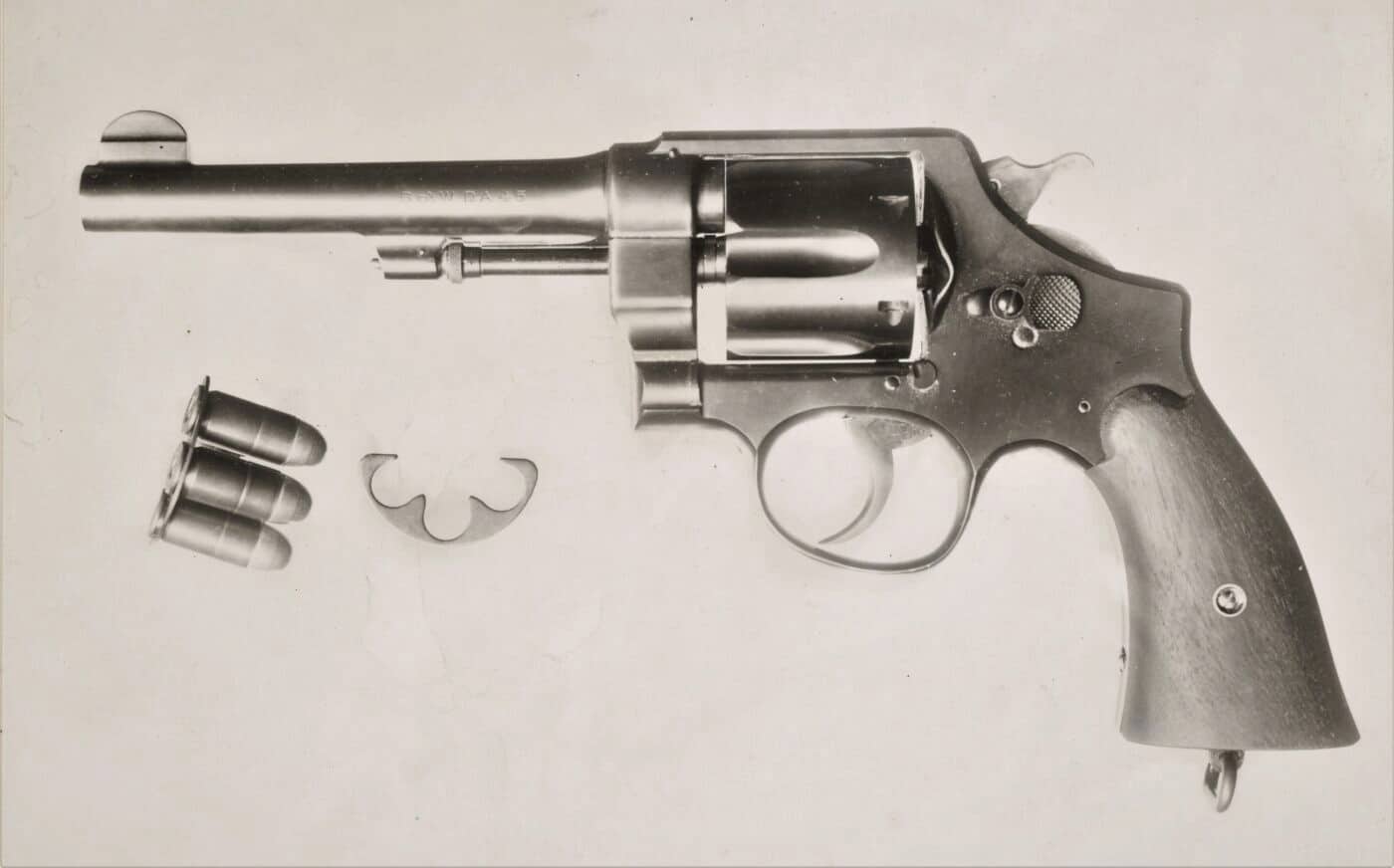

Small Arms

In addition to the bladed weapons and impact weapons, U.S. troops also had access to some fearsomely capable small arms designed for close-range combat.

M1911 Pistol

As most pistol shooters know, the .45 ACP M1911 is a handful of handgun. The .45 automatic was greatly favored by American trench raiders for its man-stopping firepower. (Read more about the M1911 in World War I here.)

Alongside the M1911, the .45 ACP M1917 revolver was also popular, and it packed just as deadly a punch. As cops carrying backup guns know, one pistol is good, two is better, and many Doughboys carried a second pistol during a trench raid — often using a captured German Luger, Mauser pistol, or one of the many smaller caliber German semi-auto handguns.

Trench Gun

There has been a fair amount of controversy surrounding the Doughboys’ use of the M1897 12-gauge shotgun, or trench gun. The Germans complained it was a violation of the law of war (specifically Article 23 of the 1907 Hague Convention) and claimed that it showed that American troops were not only inept marksmen but also barbarous. The Germans further claimed that any American captured with a shotgun (or shotgun ammunition) could be subject to summary execution. The U.S. government responded quickly: “Inasmuch as the weapon is lawful and may be rightfully used, its use will not be abandoned by the American Army…”

U.S. officials also responded that they knew exactly what to do in the way of reprisals should any American soldier taken prisoner be harmed, stating, “If the German Government shall carry out its threat in a single instance, it will be the right and duty of the United States to make such reprisals as will best protect the American forces, and notice is hereby given of the intention of the United States to make such reprisals.” Uncle Sam wasn’t messing around, and the Germans quickly backed down. Given the fact that the Germans introduced poison gas and flamethrowers to the battlefield in WWI, shotguns seemed a curious objection for the Kaiser’s men to have.

For its part, the trench gun was a fearsome close-range weapon. Fitted with a perforated heat shield above the barrel, and a lug to accept the M1917 bayonet, the trench gun has an intimidating profile. Hold the M1897’s trigger back, and you can slam-fire five rounds of 00-buckshot (with nine .32 caliber pellets in each shell) in an exceptionally short time — perfect for clearing a trench or providing suppressing fire to cover a withdrawal. Most of the 00 buckshot shells issued during World War I used a paper casing, and these could cause jamming issues if the shells were allowed to get wet. Some all-brass shotgun shells were issued but ordnance officers generally burst into tears over the cost of all-brass shotgun shells.

Laurence Stallings recounts in “The Doughboys”, that the trench shotgun was the weapon of choice for some: “One of the 33rd’s Medal of Honor performers was First Sergeant Johannes S. Anderson. First Sergeants were armed with the Army’s brutal .45 automatic, which left an exit hole in a man’s back the size of a derby hat; but the Chicago sergeant, undergoing much hostile fire to reach a concrete pillbox, made his entrance through the stage door of the pestiferous machine gun nest bearing a sawed-off shotgun. Two buckshot blasts and the twenty-three performers left on their feet surrendered. Like Sergeant Gregory, a mile to his right, Anderson was scornful of conventional weapons, and there were others who felt the same.”

Conclusion

Combat in the trenches of World War was simultaneously modern and medieval, but always brutal. And these capable — yet terrifying — close-range weapons made it even more so.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

382

382