Molotov Cocktail vs. Tank: A History of This Desperate Measure

March 3rd, 2022

13 minute read

The recent Russian invasion of Ukraine has shocked the world. Meanwhile, the response of the Ukrainian people has been equally surprising (and also inspiring), as their government has issued automatic rifles to ordinary citizens, and a modern militia army quickly rose to fight the invaders.

Along with some basic firearms training, Ukrainian officials provided instructions for the creation and use of Molotov cocktails, the time-honored anti-tank weapon of last resort. Looking back, the Molotov cocktail was notably used by the Hungarians in their uprising against the Soviets (October 23rd to November 11th, 1956) and to a lesser extent during the Czech Uprising of August 1968.

We’ll take a look at how this simple incendiary has been served up to invading armies for more than 80 years.

Origin of the Flaming Cocktail

The term “Molotov cocktail” originated from the local response to another Russian invasion, this time in Finland during late 1939. As the Red Army pushed into Finland, Soviet bombers began to indiscriminately bomb civilian targets in Helsinki.

Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov described the bombs dropped in these raids as “food parcels” provided to the hard-pressed Helsinki residents. After that, the Finns referred to Soviet cluster bombs as “Molotov Bread Baskets”.

Shortly afterwards, as Finnish troops fought desperately to hold back Soviet armored attacks, the glass bottle gas-bombs were called “Molotov cocktails”, an appropriate drink to go along with Molotov’s propaganda food deliveries. Today, nearly 83 years later, those same cocktails are being served up for Russian troops and tanks yet again, this time in Ukraine.

Man vs. Tank

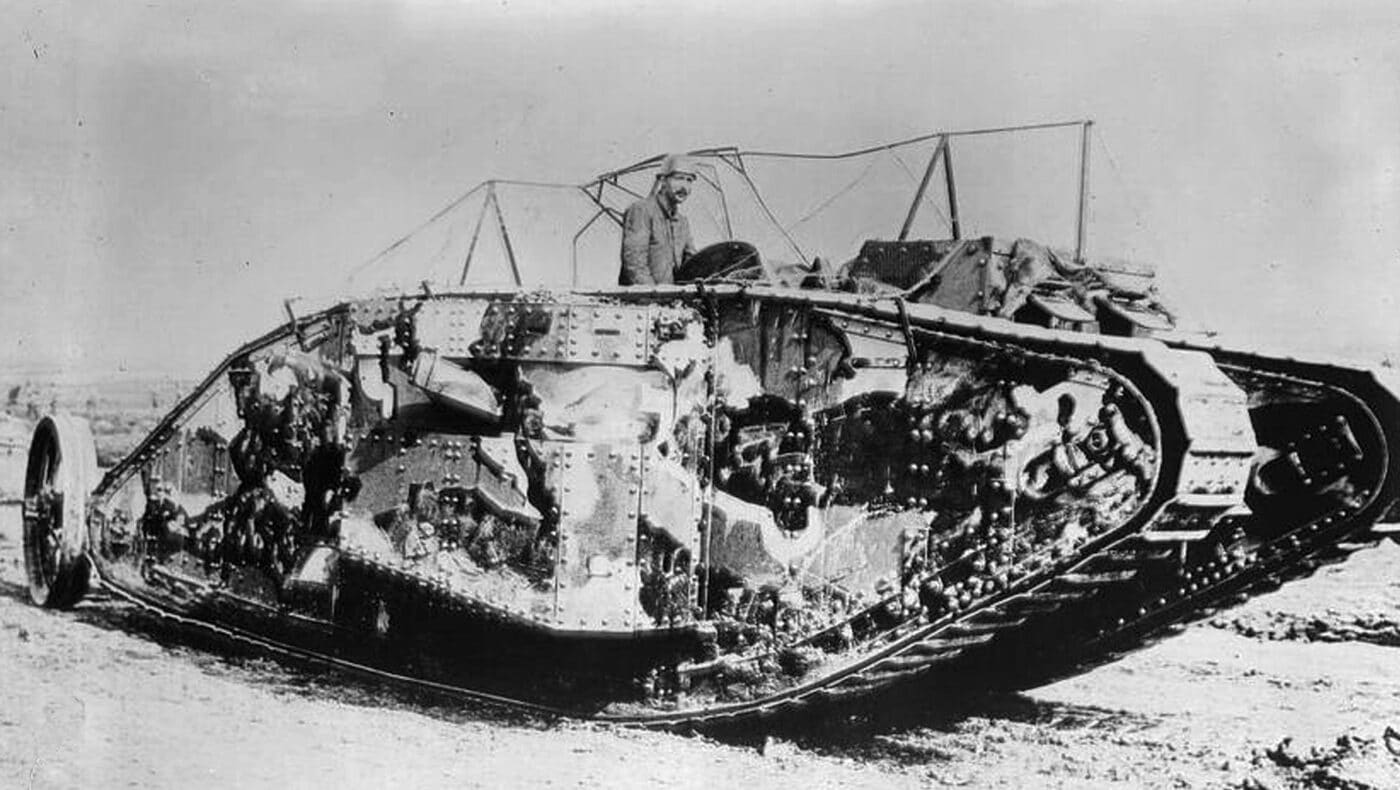

When tanks first appeared on the battlefield during World War I, there were no specialized weapons or tactics available to fight them. The German troops facing these armored, albeit slow-moving, monsters were at first obliged to run for their lives.

Unfortunately for the British tankers operating on the Somme in the late summer of 1916, their Mark I tanks were plodding vehicles, mechanically unreliable, and particularly difficult to see out of due to their rudimentary hatches and vision ports. Captured examples provided the Kaiser’s troops with better ideas of how to fight their new armored opponents, and German industry quickly set out to develop specialized weapons for that purpose. In the meantime, German infantry anti-tank doctrine focused on close assault tactics.

Germany’s World War I “tank hunters” frequently used smoke grenades to blind the tanks, and then special bundled charges, made from several stick grenades wired together and fired by the central grenade, were thrown onto the roof of the vehicle, or under the tracks. The explosion was normally enough to cave in the roof, disable the crew or engine, or blow off the track.

There were examples of German troops firing pistols in through gaps in the armor, and on at least one occasion they tried to pull the tank’s machine guns off their mounts and out of the vehicle. When possible, flamethrowers were used in the anti-tank role, but by the end of the Great War most German anti-armor weapons were focused on engaging the boilerplate coated vehicles from a safe distance.

The Spanish Civil War

The years after World War I saw little peace, and some of the conflicts became proving grounds for the weapons and tactics of World War II. This was particularly evident in the Spanish Civil War, where the Soviet Union sent T-26 and BT-5 tanks to equip the Spanish Republic’s army, and they joined in combat with the two-man L3/35 tankettes of Italy’s Corpo Truppe Volontaria, and the equally tiny Panzer One light tanks of Germany’s Condor Legion.

The early days of the Spanish Civil War featured very few purpose-built anti-tank weapons, and for a time the armored vehicles reigned supreme. However, much of the fighting was at very close quarters, and troops on both sides quickly learned the effectiveness of the cheap and easy-to-build gasoline bombs.

In John Weeks’ excellent book “Men Against Tanks, A History of Anti-Tank Warfare” (Mason/Charter 1975), he describes the first widespread use of the Molotov cocktail, slightly before the weapon received its name:

“The Spanish had no effective answer to the tank; in desperation they resorted to hand-to-hand fighting. Men lay in ditches and trenches until the tanks were almost upon them, and then leapt out and climbed on top, firing into vision ports, jamming crowbars into hatch covers and gun mantlets, and pouring petrol into the engine compartment and lighting it.

“The ‘Molotov cocktail’ (was) a mixture of petrol or benzene, water and phosphorous with a piece of rubber added to make a sticky jelly with the benzene. The mixture was kept in bottles and just before throwing, it was shaken vigorously. On hitting a hard surface, the bottle smashed, the phosphorous ignited in the air and the benzene blazed merrily. A pint or so of burning petrol did not deter a tank very much, but in time the smoke was pulled into the crew compartment and the usual effect on the crew was to cause such alarm that they stopped and bailed out.

“In any case, the tanks of 1936 were all petrol-driven and the fuel tanks could be set alight if enough Molotovs were thrown. Molotovs are dangerous things both to carry and to throw, but the next weapon was even worse. This was a specialty of the Asturian miners of northern Spain. They invented the satchel charge, which is simply a cloth bag filled with blasting explosives and fitted with a short-burning fuse and a pull switch.”

The tanks of the time were much smaller than we think of today, and they were vulnerable to Molotovs if the enemy was able to get in close enough to use them. Petrol-soaked blankets and rugs were also used, and close-assault anti-tank tactics in Spain normally featured attacks against the vehicles’ running gear with crowbars, lengths of heavy pipe, or even railroad ties shoved into the tracks.

The “mobility kill” presents a terrible situation for the crew of the immobilized tank, and the prized target of roving groups of tank hunters. In this scenario, the Molotov cocktail and the satchel charge have been effective weapons for nearly 90 years, and they remain so today.

The Soviet-Finnish Winter War

When the Soviet Union invaded Finland on November 30, 1939, the world became familiar with the term “Molotov cocktail”, and Russia’s habitual aggression on its neighbors. In mid-September 1939, the Soviets had attacked Poland from the east, while Nazi Germany invaded from the west.

Two months later, Stalin set his sights on Finland and long columns of Russian tanks and trucks began to pour onto the narrow Finnish forest roads. The hardy Finns were extremely aggressive in their defense, their troops often overflowing with “sisu” (guts), and Molotov cocktails and satchel charges became critical components of their early anti-tank defense.

At the time of the invasion, the Finns had barely 60 days’ supply of ammunition of any sort, and glass bottle gas bombs were both a financial necessity as well a tactical one. Even as Soviet tanks grew in size, firepower and armor protection, the Molotov cocktail remained as a part of the Finnish arsenal, serving through the Continuation War against the USSR from June 1941 until September 1944. By the end of the Winter War in March 1940, the Soviets had lost more than 3,000 tanks in Finland, many of them abandoned by their crews in fear of the Finnish tank hunters.

Britain’s Home Guard

After Germany’s lightning victory in Western Europe during the battles of the spring of 1940, Britain found itself facing the Nazis alone. Fears of invasion in the British Isles were rampant and were not completely unfounded.

After their armored charge across Belgium and France, Hitler’s Panzer had become the stuff of British nightmares, and anti-tank weapons in the UK were few. The British Home Guard looked to the Molotov cocktail as a ready answer to fight the potential menace of German tanks on British streets.

John Weeks details a rather optimistic anti-tank method offered in Home Guard defense manuals in his book “Men Against Tanks”, stating “There was much wishful thinking and misleading advice about stopping tanks” in England at that time:

“There is another way in which tanks can be stopped by brave men. Where the path that they will take comes close to thick cover, or consists of a narrow village street, you can wait for them with crowbars, lengths of tramline or similar metal. This is a job that is best done from the open doorway of a house against a tank traveling fairly slowly and very close to the house. The metal bar must be thrown or rammed into the side of the tank so that it gets in amongst the gear wheels and bogie wheels of the track. If a tank is traveling fast, the bar will probably be jerked from your hand, and you will fail to get it in among the works. But if you can get it properly placed, the tank will be stopped and will probably block the road for those following it. For smaller tanks, a pick slung into the tracks from the side will sometimes do the job.”

Other British leaders noted that the Molotov cocktail was often as dangerous to the user as it was to the enemy, with some sources claiming that up to 10% of gas bomb users suffered serious burns before they made their attack. That figure appears to hold true even now, particularly among irregular or militia forces.

Germany’s Panzerknackers

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, German troops encountered many of the T-26 and BT tanks they had seen in action in Spain, and again in Finland. To their dismay, they also found the next generation of Soviet tanks, the advanced T-34 medium tank, and the well-armored KV series of heavy tanks.

In that awful moment of discovery, German infantrymen found that their prime anti-tank weapon, the 37mm Pak 36 AT gun, was woefully inadequate. Consequently, the Wehrmacht had to learn and adopt aggressive close-assault anti-tank tactics, and the Molotov cocktail became a part of the “Panzerknacker” arsenal. German troops adapted the gas bomb idea with a larger field modification, using a five-gallon Jerrycan of gas ignited by a standard M24 stick grenade.

German infantry anti-tank manuals and training materials show all kinds of bizarre recommendations for fighting tanks with strange means — hammering exposed machine gun barrels with crowbars, inserting grenades into the tank’s main gun barrel, even chopping through the vehicle’s ventilation louvres with an axe to pour gasoline into the engine compartment and ignite it. Any of these methods may have worked once or twice, but the tactical conditions needed to be exactly right, and the troops extraordinarily motivated to attempt it.

Japan

Japan’s first experience with anti-tank tactics came during their battles with the Soviets in the Khalkhin Gol region on the Mongolian/Manchurian border. During the sporadic engagements from May through September of 1939, Japanese troops armed themselves with gasoline bombs as expedient anti-tank weapons.

Japanese use of Molotov cocktails continued during World War II. The following is a description of one of these Japanese weapons from a U.S. Intelligence Bulletin, dated March 1944:

Japanese Molotov Cocktail

1. DESCRIPTION

The Japanese have a type of Molotov cocktail which differs from other similar weapons in two main respects, namely:

a. It has a fuze.

b. It will fire when thrown against ordinary ground as well as against hard objects.

The weapon consists of a 12-ounce glass beer bottle (which is 9.5 inches high, 2.4 inches in diameter at the base, and 1 inch in diameter at the top), an inflammable liquid compound, and a combined burster and igniter fuze.

The fuze will activate the weapon at any position the weapon may strike a surface—it is called an “all-ways” fuze for this reason. The burster and igniter fuze combination comes in a separate cylindrical metal container, which is 2.45 inches high and 1.4 inches in diameter. It is sealed with gum paper. The fuze is threaded to screw into a metal lining which fits inside the neck of the bottle. A rubber washer enables the bottle to be liquid sealed. The fuze also has a safety pin with an attached string—which is used to extract the pin before the Molotov cocktail is thrown—and a protective cover.

The Japanese have used at least three kinds of explosives in this weapon. Besides an inflammable compound, some have been found with 91-octane gasoline and some with a gasoline and oil combination—75 percent gasoline by volume and 25 percent heavy oil by volume.

2. OPERATION

The following instructions on operation were translated from Japanese sources.

a. Assembling

Fill the bottle with inflammable chemical compound. Remove the fuze from the fuze container, and, with the fuze cover still on, screw the fuze tightly onto the bottle.

b. Using

Immediately prior to taking up the approach march for the attack, throw away the protective cover for the fuze.

When about 10 yards from the objective, pull out the safety pin in the fuze, and throw the weapon against the upper section of the motor [presumably of a tank]. The effect will be greater if two or three bottles are thrown in succession.

c. Precautions

After pulling out the safety pin, do not drop the bottle or hit it against a hard surface.

If there is no target after pulling out the safety pin, throw the weapon a considerable distance away, or find some other way of disposing of it, as a safety measure.

As World War II progressed, Japanese anti-tank weapons lagged in effectiveness with the appearance of American vehicles like the M4 Sherman tank. By 1945, the Japanese deployed many desperate anti-tank measures, including the use of suicide bombers strapped with satchel charges — the men throwing themselves beneath an American tank to explode their charge against the thin belly armor.

American Forces

The construction and use of Molotov cocktails was no secret to U.S. troops, and examples can be found of their use in World War II training, particularly at the Chemical Warfare Training Center at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. However, I have never found any after-action reports that detail American use of the Molotov cocktail in combat.

In preparing this article, I was reminded of a scene in the Steven Spielberg film “Saving Private Ryan” (1998), where American paratroopers dropped Molotov cocktails into an open-topped “Marder” tank destroyer. The resulting explosion and fire in the cramped fighting compartment of that vehicle is quite dramatic, and entirely realistic. I asked the film’s military advisor, USMC Captain Dale Dye, what he used as inspiration for that scene. This is what he said:

“Interesting query that set me to thinking about how we staged the final assault at the bridge in Saving Private Ryan. I did reference actual battlefield reports about hand-launching 60mm mortar rounds from a decoration citation from a fight in Italy circa 1943.

“As for the Molotov cocktails, what I recall is that director Steven Spielberg had me diagram the battle as I saw it being conducted in real life and telling him how I would do it if I was the senior officer on that ground. Given the lack of anti-armor weapons available to the Rangers/Paratroopers defending the town, I imagined that they would fall back on whatever destructive devices were at hand.

“The ‘sticky bombs’ were in Roger Rodat’s script using C-2 explosive blocks, socks and sticky substances. The writer had included that type of improvised weapon but didn’t provide details, so I worked out how they would be constructed and included the thought of wine bottles, fuel, a make-shift fuse to create Molotov cocktails for use against thin-skinned armor.

“That was not scripted but Spielberg liked it, so we ended up using it. I don’t recall any specific historical references to the Molotovs, but it seemed like something desperate men under fire would do.”

Conclusion

Captain Dye is right, of course. The pages of military history rarely record the specifics of what desperate men and women do in the ferocious struggles that take place in their little corner of Hell.

As history repeats itself, over and over again, the use of Molotov cocktails, smashed against the side of an invader’s tank, are witnessed time and time again. Today is no different; all you have to do is look to the bravery of the Ukrainian people in their fight to remain free.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

540

540