My Caliber Crisis: Do I Need a 10mm?

September 30th, 2019

4 minute read

I’m having another caliber crisis.

Over the years, I’ve ventured into cartridge odysseys that include unusual chamberings like .357 Sig and 300 Blackout. More recently, I’m kind of developing a thing for 10mm. I’ve been testing out a Springfield Armory Range Officer Elite Operator chambered in the big-boy version of the .40 S&W and I’m kinda liking it. There are definitely some benefits. Let’s discuss.

Weight and Velocity

We’re going to argue forever about whether the light, small and fast 9mm is as good as the heavy, fat and slow .45 ACP, so why not just choose heavy, moderately portly and fast?

The 10mm, when fired from the Springfield Armory Range Officer Elite Operator, launches 200-grain bullets in the 1,100 feet per second velocity band. That’s the mid-weight of the .45 ACP bullet family and the mid-velocity range of 9mm.

How Powerful Is a 10mm Auto?

Many stand in awe of the 10mm, likely because it has a simple, yet badass name. Then there’s the fact that the FBI moved to it (sort of) for a time. It’s hard to argue with credentials like that.

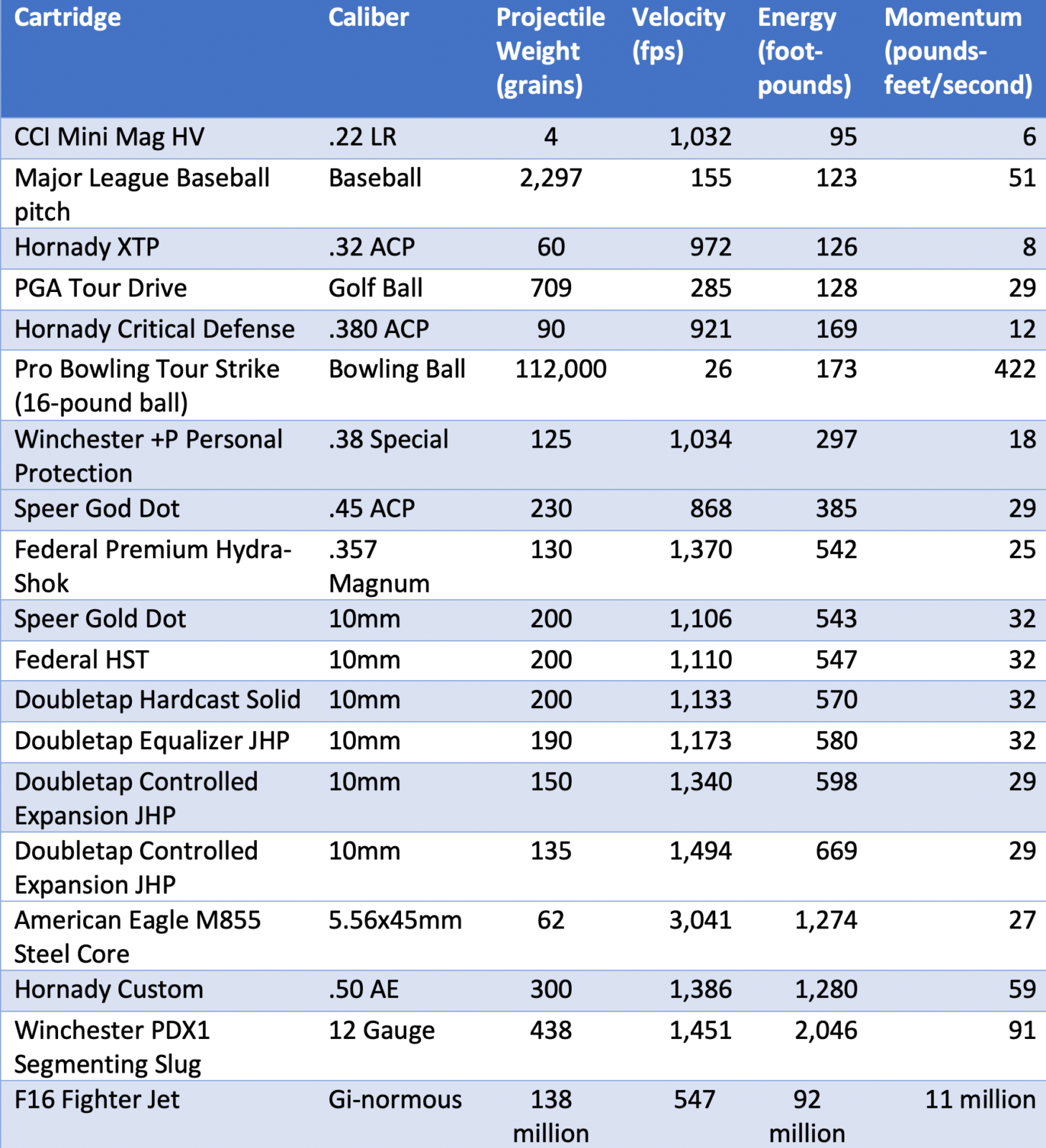

Being the inquisitive sort, I wanted to see how it stands up to all the other common cartridges and a few other kinetic energy-generating objects. So, I dug up my database from all the ammunition and guns I’ve tested over the years and looked up a pile of actual cartridge, velocity, kinetic energy, and momentum calculations for some representative samples.

As a side note, I like to look at both kinetic energy and momentum to tell the whole story of how “powerful” a cartridge is. Kinetic energy is easy — we all know “foot-pounds” as a standard measure of “oomph.” However, kinetic energy emphasizes velocity the way it’s calculated, so a super-light bullet can have huge foot-pound numbers simply because it’s moving fast. The slow and fat projectile crowd likes to take bullet weight into consideration and that’s where the momentum calculation comes into play.

At the risk of insulting physics, you might think of kinetic energy as destructive power, like a power drill. And you might think of momentum as the ability for one object to move another. The more weight the “mover” object has, the more powerful it is. Think wrecking balls. They don’t move all that fast, but few of us would want to be hit with one.

Anyway, I fired several different loads from the Springfield Armory Range Officer Elite Operator pistol you see in the picture above and recorded velocity so I could run the numbers. Just for fun, I did the math on a few other non-shooting moving objects and added in info on several other chamberings.

So, what does all this mean? Here are the important learnings.

The 10mm mostly tops the charts for “rational” handgun power levels. Sure, a .44 Magnum brings half again more kinetic energy, but unless you’re Dirty Harry, it’s not the most practical carry handgun.

If you’re a foot-pounds junkie, 10mm thumps 9mm, .40 S&W and .45 ACP.

The 10mm and .357 Magnum are similar from a kinetic energy perspective. While the .357 Magnum uses a much lighter projectile, it moves a lot faster, hence the high foot-pound count.

Frankly, the Federal 10mm HST load is impressive. It delivers nearly as much energy as the niche 10mm loads but with the proven hollowpoint used by police officers and others for self-defense. For personal protection, it is tough to beat.

A 10mm has about the same momentum as a PGA drive launched by Bubba Watson, although I’m pretty sure the 10mm projectile will win handily in the penetration and expansion tests. Sorry Bubba.

Capacity of a 10mm Pistol

There’s nothing to write home about here. Normal capacity for a 10mm is virtually identical to that of a .40 S&W. That’s because the case diameter is the same, although the 10mm cartridges are longer. Remember, the whole point of the .40 S&W “great compromise” was to offer more capacity than a .45 ACP pistol while launching larger bullets than a 9mm.

But What About 10mm Recoil?

I think the real recoil penalty (or lack thereof) is what makes the 10mm interesting. While it’s not as easy to control as a 9mm or .40 S&W, it’s not all that different from that of a .45 ACP pistol of the same weight. What you feel as recoil depends largely on the weight of the pistol, so if you’re comparing a steel 1911 chambered in .45 ACP to one packing 10mm, the numbers work out about the same.

I won’t bore you with the common-core math details, but the recoil energy of a .45 ACP 1911 and 10mm 1911 works out to 5.43 and 6.28 foot-pounds. To put those numbers in perspective, the same math on much lighter Springfield Armory XD-S pistols in 9mm, .40 S&W and .45 ACP works out to 5.07, 6.92 and 8.15 foot-pounds.

The Bottom Line

Here’s my take. If you want a gun that’s super-duper easy to control so you can deliver rapid-fire strings without the sights moving, buy a steel 9mm like a Range Officer or EMP. If you want more power in a semi-automatic package that’s as carry friendly as a .45, consider the 10mm. You might fit an extra round or two in a gun of similar size owing to the smaller cartridge diameter while fulfilling your need for speed.

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

318

318