Over There: World War I War Posters

August 25th, 2020

8 minute read

When the Great War began in August 1914, none of the world’s leaders could have predicted the horrific loss of life would follow. In a little more than four years, World War I produced more than nine million battlefield deaths. The conflict consumed most of a generation of European men.

While European empires crashed headlong into war, more than 70 percent of American voters had no interest in becoming involved in what they considered a “European conflict.”

Many Americans had only recently arrived in the United States as part of a large wave of immigrants from Central, Eastern and Southern Europe. Most of them preferred to keep European problems in their rearview mirror and concentrate on their new life in America.

Leaning Toward Isolationism

The August 1914 to April 1917 period proved to be particularly lucrative for America. More Americans became millionaires during this period than in any other time in U.S. history to that time. Beyond the profitability of the era, Americans had a distinct distaste for foreign military involvement — on the whole, Americans of the era did not want to pay for it or see American soldiers die in foreign lands.

Even so, American troops fought outside U.S. borders in the Spanish-American War of 1898 (in Cuba and the Philippines), and then in the multi-national Peking Relief Mission during 1900. American troops were also fighting in the unpublicized Philippine Insurrection, a conflict that would last until 1913 and cost more than 6,100 American lives.

In April 1914, President Wilson sent the U.S. Marines to occupy the Mexican city of Veracruz, in a preemptive move to prevent German intervention in the Mexican revolution. U.S. forces held Veracruz until November 23, 1914. More trouble with Mexico would arise in the spring of 1916, stemming from the terrorist acts of Pancho Villa, and resulting in General Pershing’s hot pursuit of him (to learn more about this event, click here).

War of Attrition

In the first year of the Great War, America was barely an afterthought to Allied powers England, France, Italy and Russia. But after the offensives sputtered, and the trenches were dug, the horrible meatgrinder began. More weapons, and most importantly more men were needed for the Allied cause.

America remained firmly neutral, even after 128 Americans died aboard the RMS Lusitania, torpedoed by U-20 on May 7, 1915. Many Americans were outraged, and anti-German sentiments simmered, but heated debates in Congress did not translate into action.

By 1916, the casualty counts were growing exponentially. What had begun with eager volunteerism and a great sense of national pride had quickly degenerated into an ugly war of human attrition in Europe. As volunteers declined, conscription was introduced to fill the ranks.

Within the British Isles, conscripts were only culled from England, Scotland and Wales. Irish men were not conscripted. The British Government passed the Military Service Act during 1916, and conscription continued until 1919.

Early on there were exemptions allowed for certain types of high-value civilian work, health reasons, domestic hardship and religious conscientious objectors. Married men were initially exempt from conscription. Very soon however, precious few exemptions to military service were allowed. Ultimately, almost all British men, ages 18 to 51, were subject to conscription.

America and the Draft

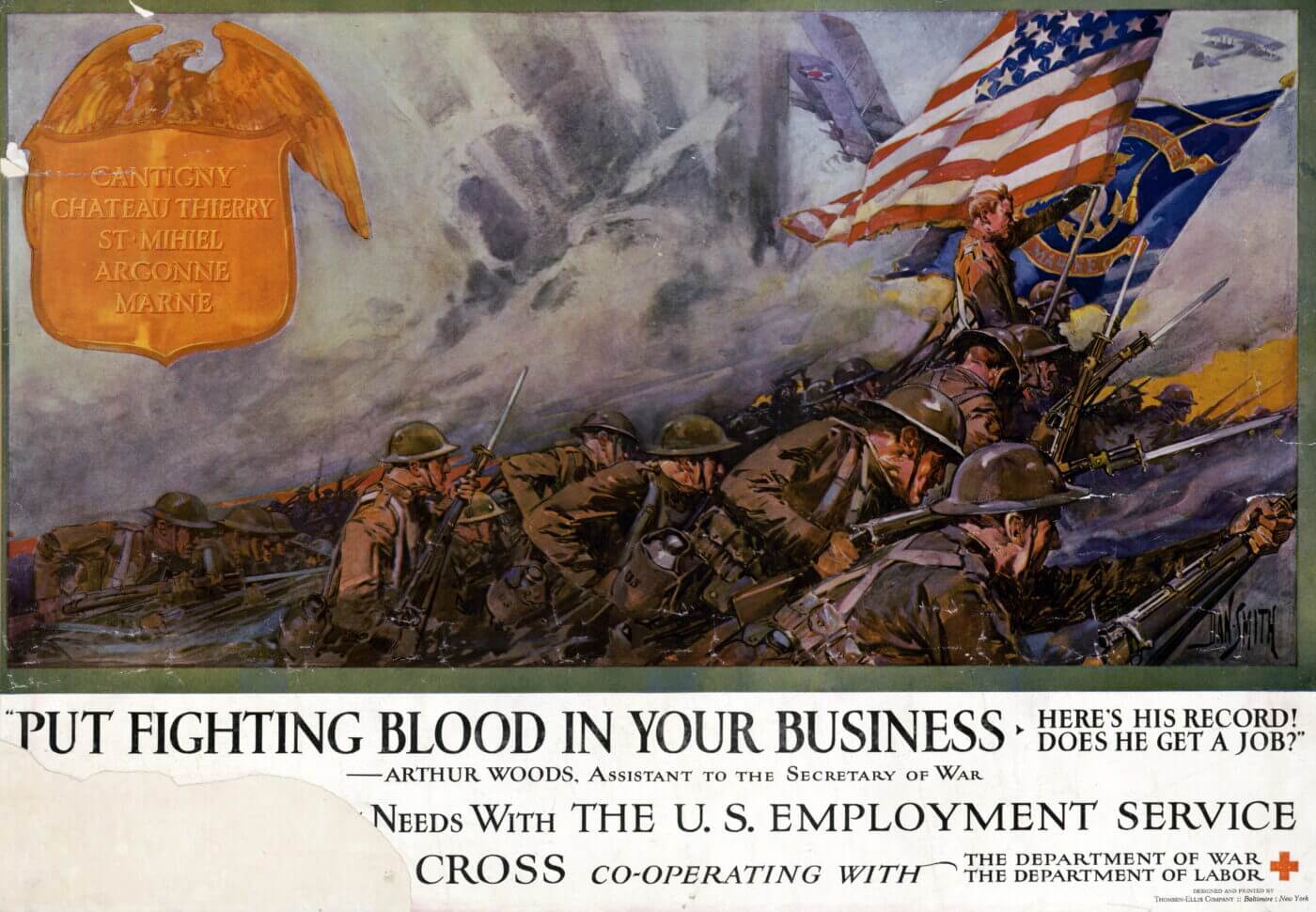

In the United States, “the draft” had been used during the Revolutionary War and the Civil War. When America entered the war in April 1917, less than 10 percent of the anticipated amount of one million volunteers came forward.

In that light, President Wilson chose to turn to nationwide conscription. The Conscription Act of 1917 saw more than 2.8 million American men, ages 18-45, brought into military service.

In the United States, exemptions for conscientious objector status was only granted to the Amish, Mennonites, Quakers and members of the Church of the Brethren. No other objections, religious or political, were allowed.

Almost 65,000 men claimed conscientious objector status, but even so, approximately 21,000 of them were inducted into the army. Most of them gave up their “CO” status and served in the military, including Sergeant Alvin York, Medal of Honor winner and the greatest American hero of World War I and one of the most celebrated military marksmen of all time (to learn more about him, click here).

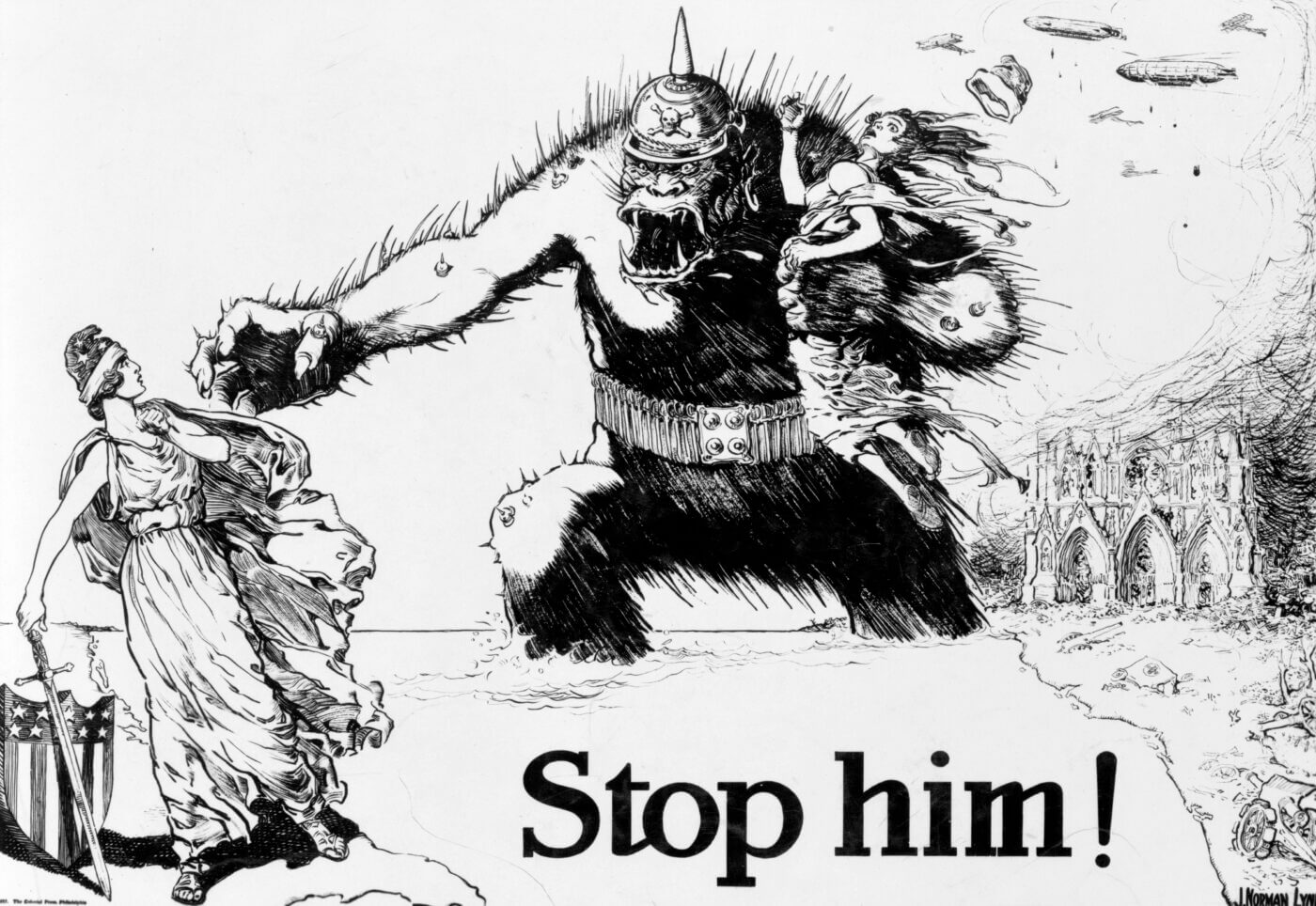

The Mad Brute

The race to motivate neutral America to take up arms against Germany faced significant challenges. A huge hurdle came from the immigrant make-up of the U.S. population, as Germans were quietly the largest immigrant group in America.

A few artists illustrated Germany and the Kaiser’s government as a murderous ape, hell-bent on violating Lady Liberty. However, few Americans ever believed that German troops would cross the ocean to invade the United States.

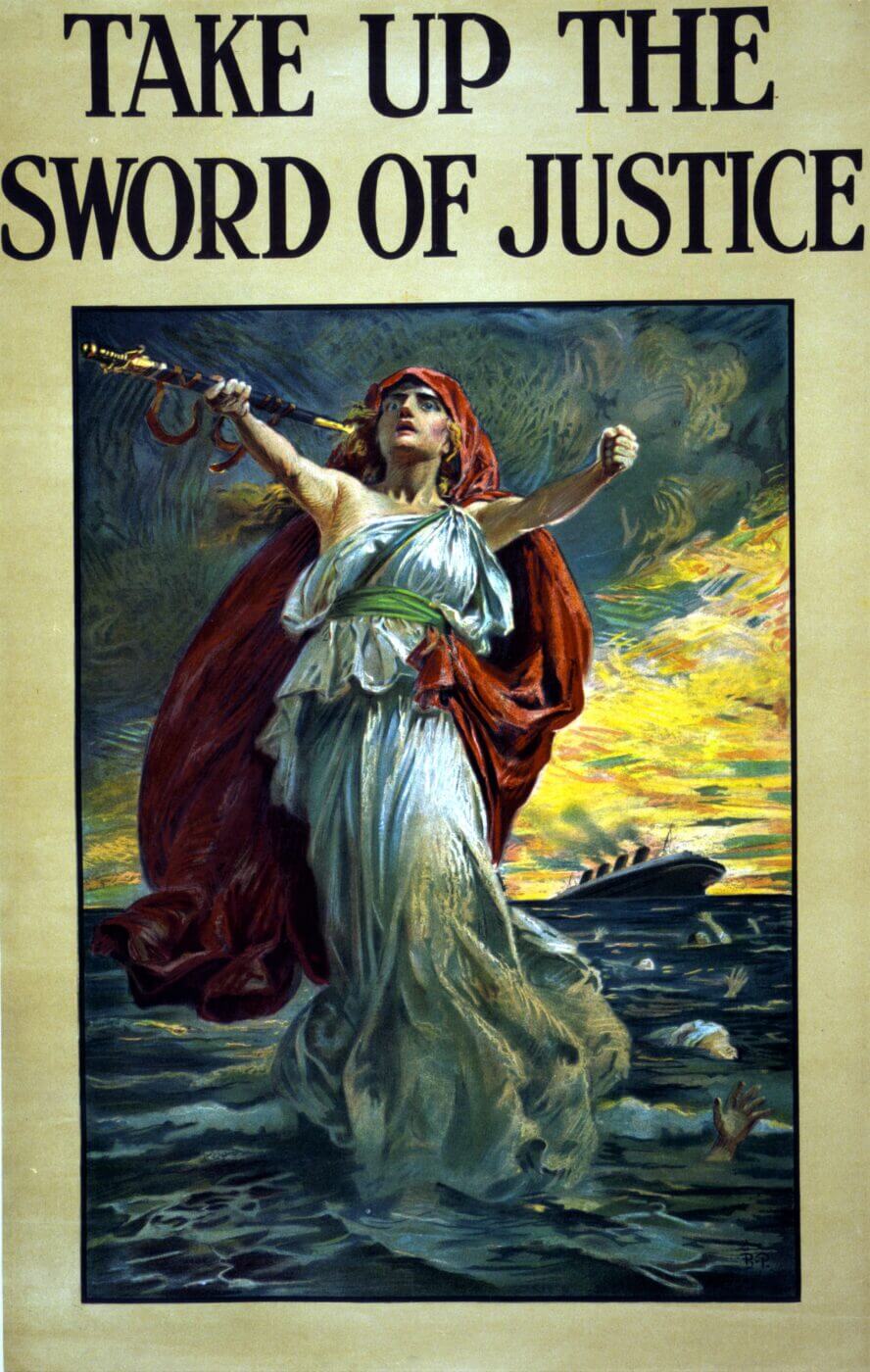

Germany’s use of unrestricted submarine warfare was condemned as murderous piracy by most nations. However, even after the sinking of the massive liner Lusitania in May 1915 claimed more than 100 American lives, the U-Boat attacks did not drive the U.S. to quickly enter the war.

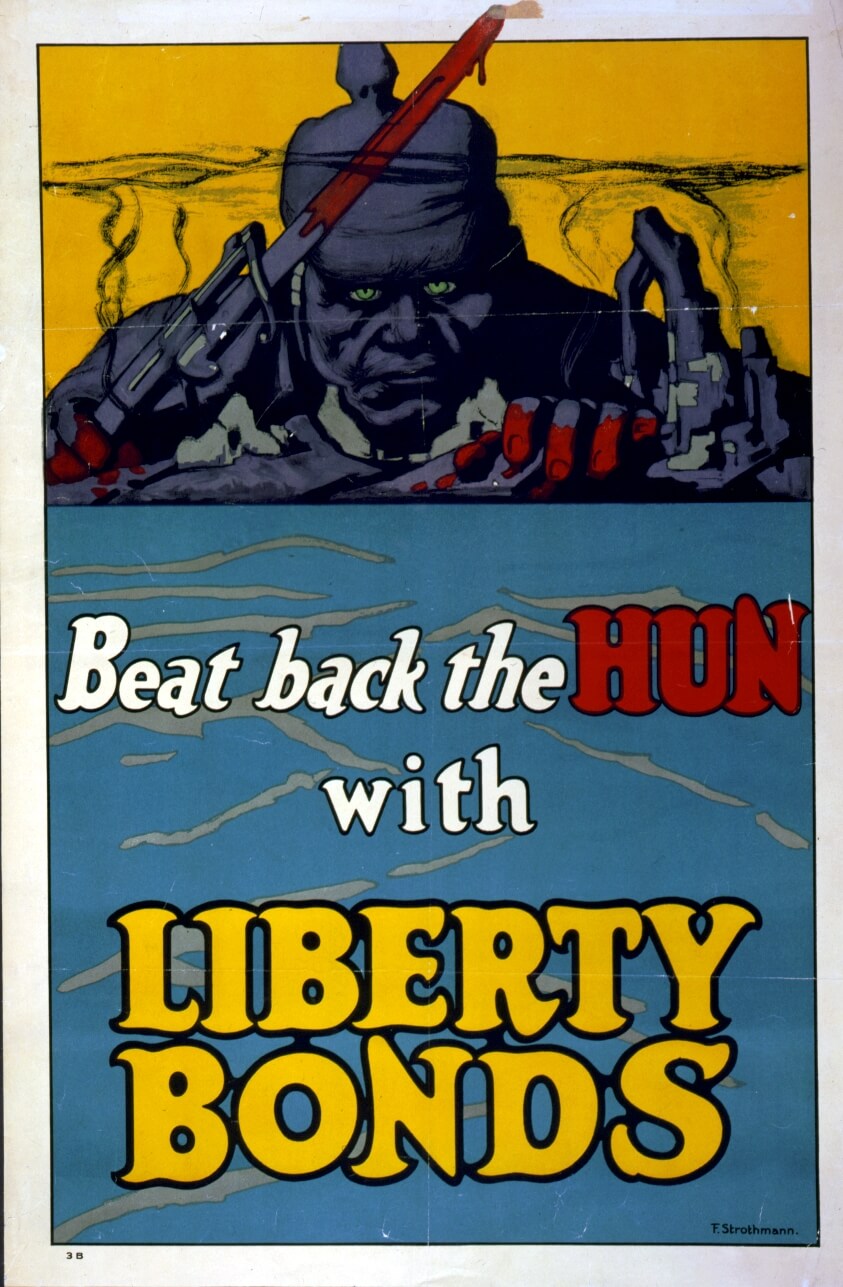

The Allies advanced many tales of German barbarism in their occupied territories, particularly Belgium. As 1917 began, new propaganda campaigns were developed to help convince America to join the fight against Germany.

Images of German troops were shown in human form, albeit hulking, brutish and blood-soaked. “Keep him out of America” became a theme.

American Firepower

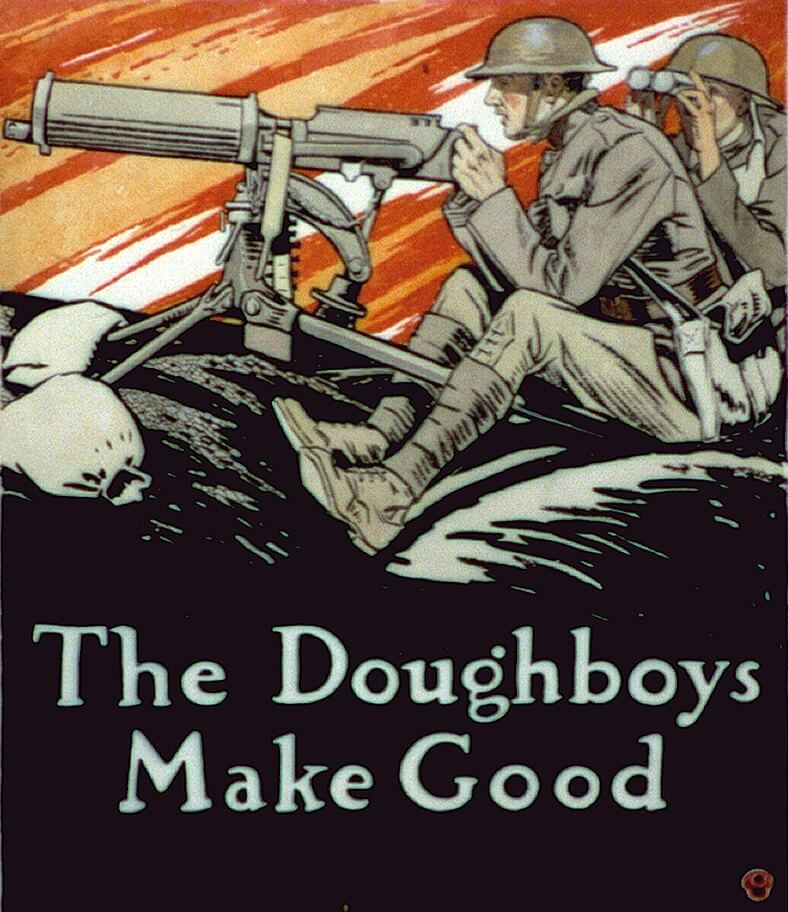

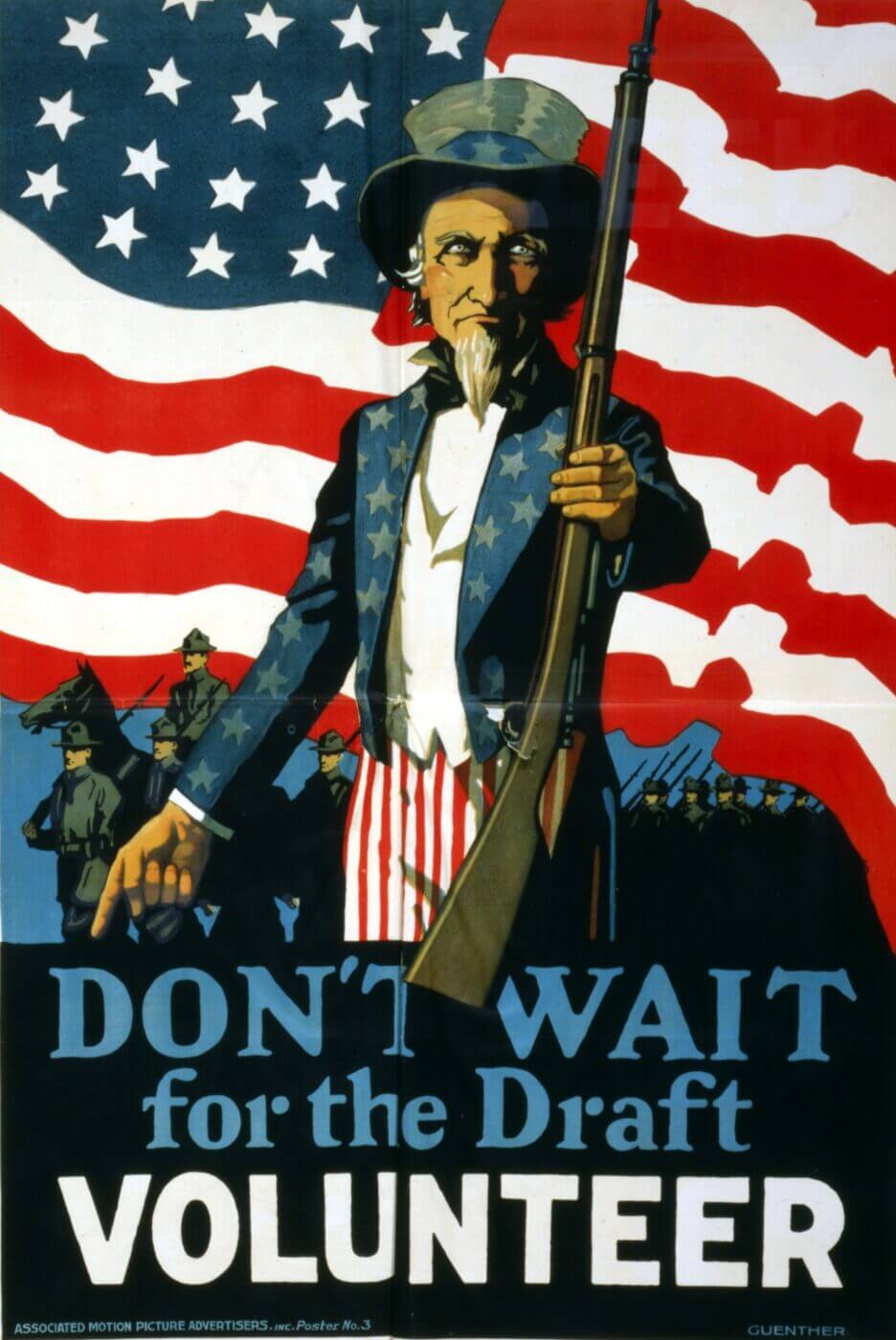

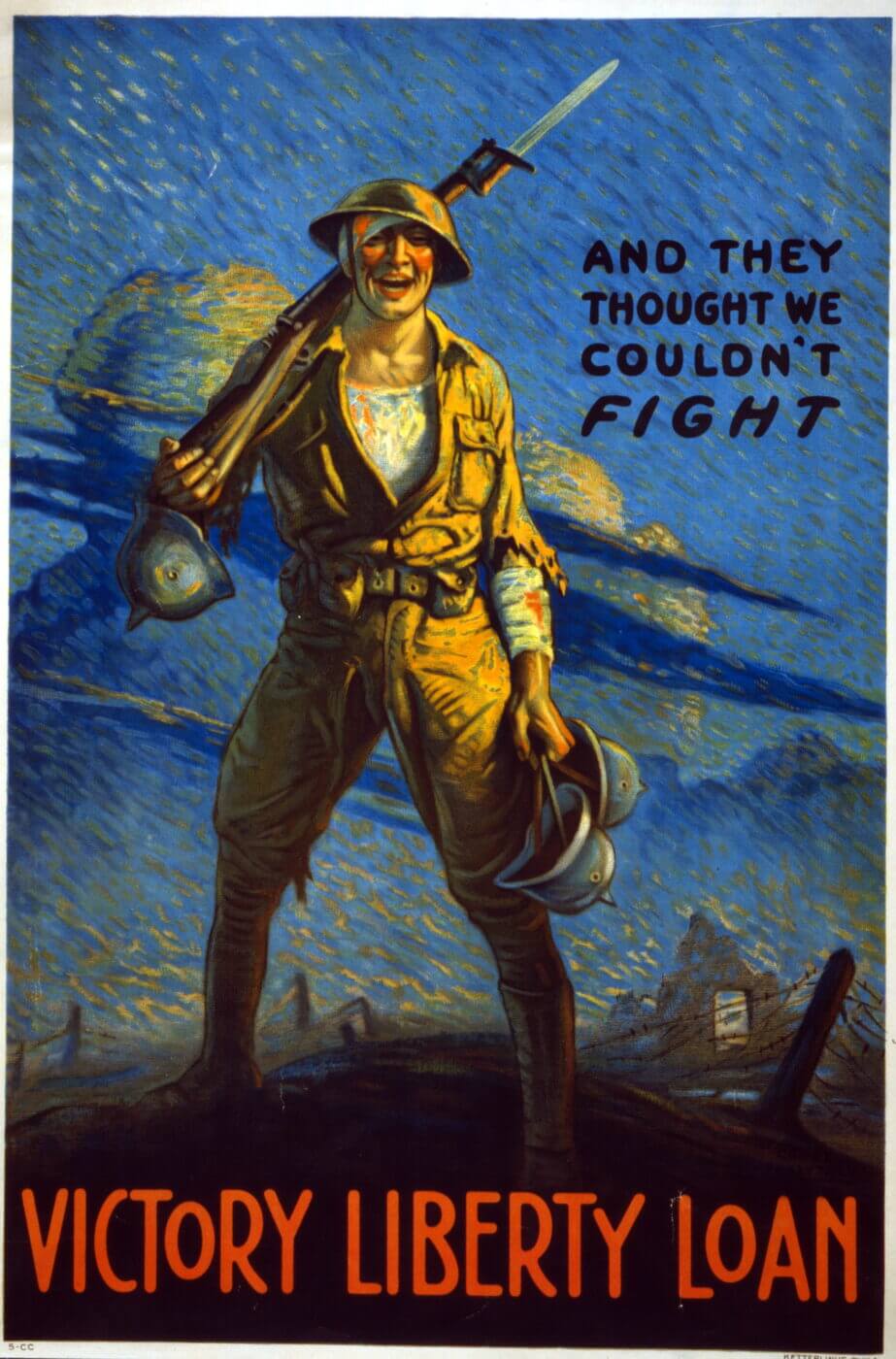

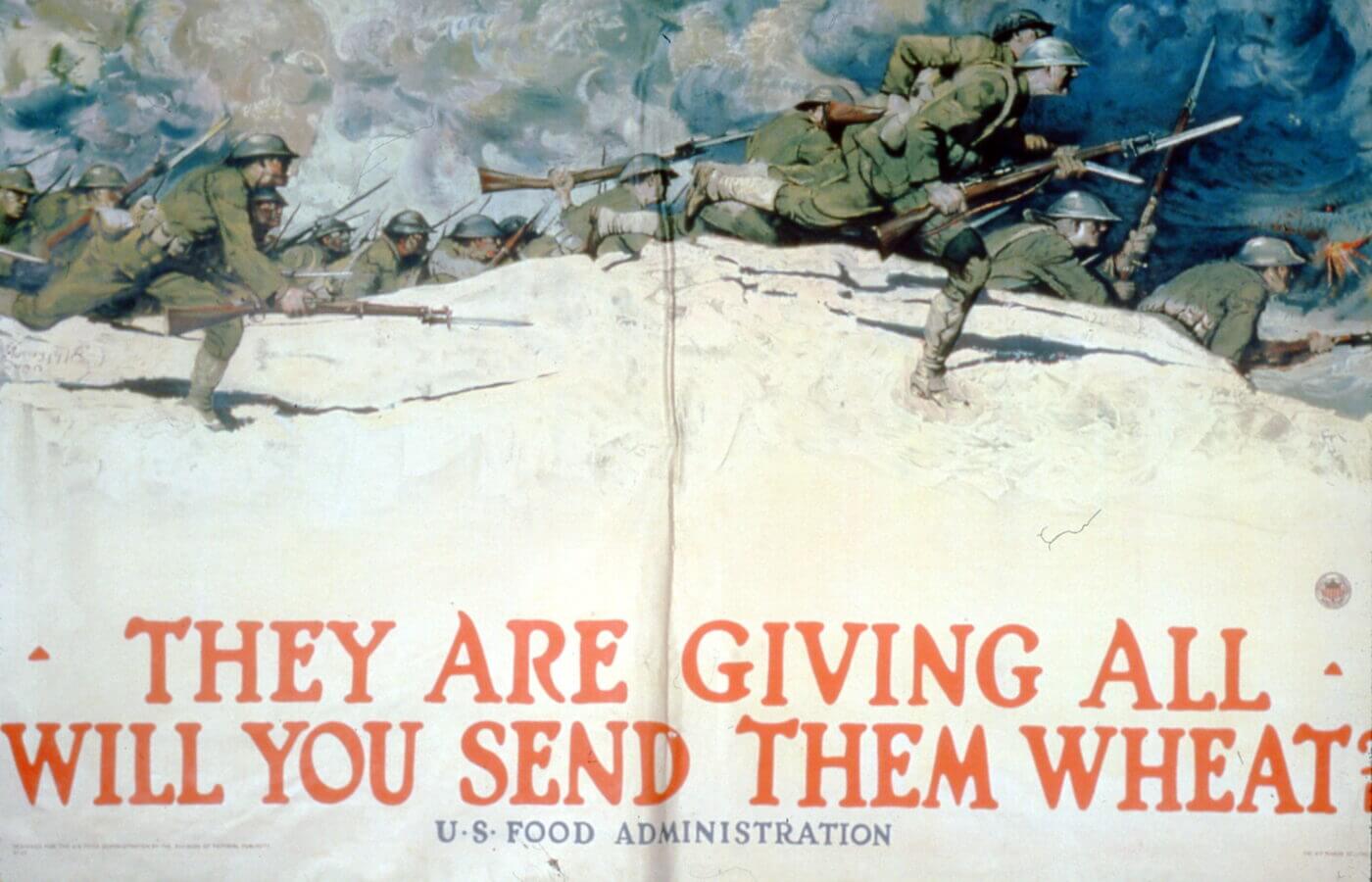

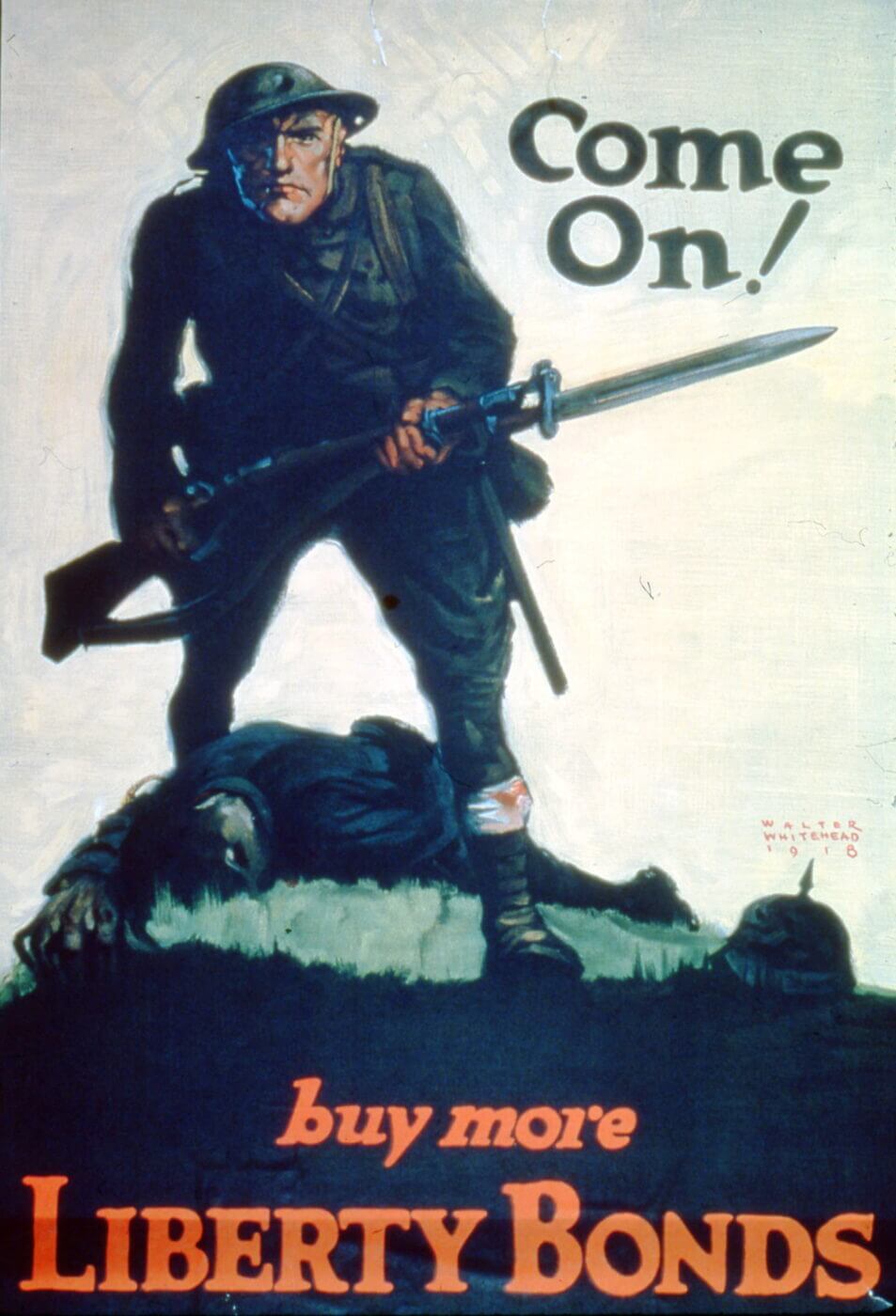

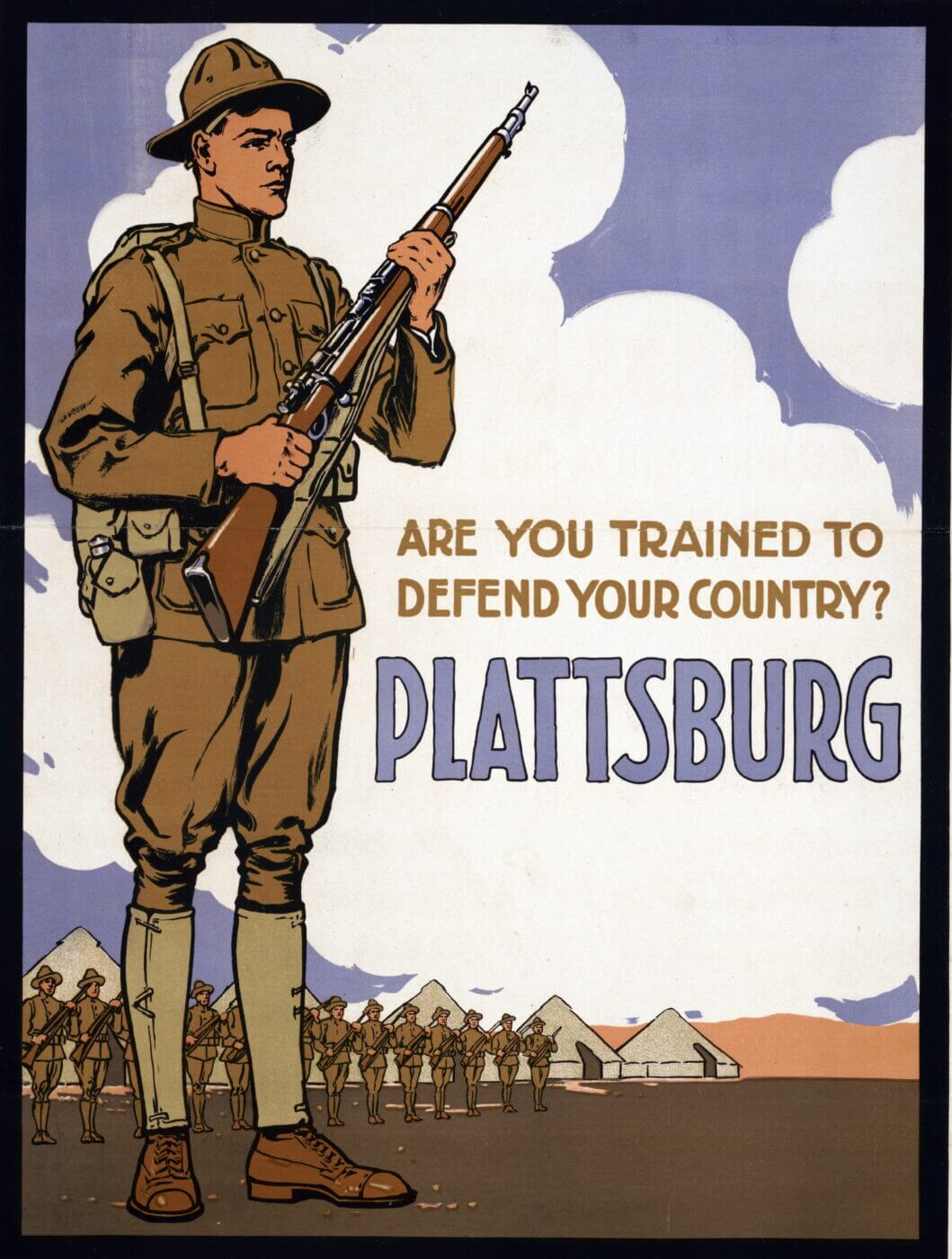

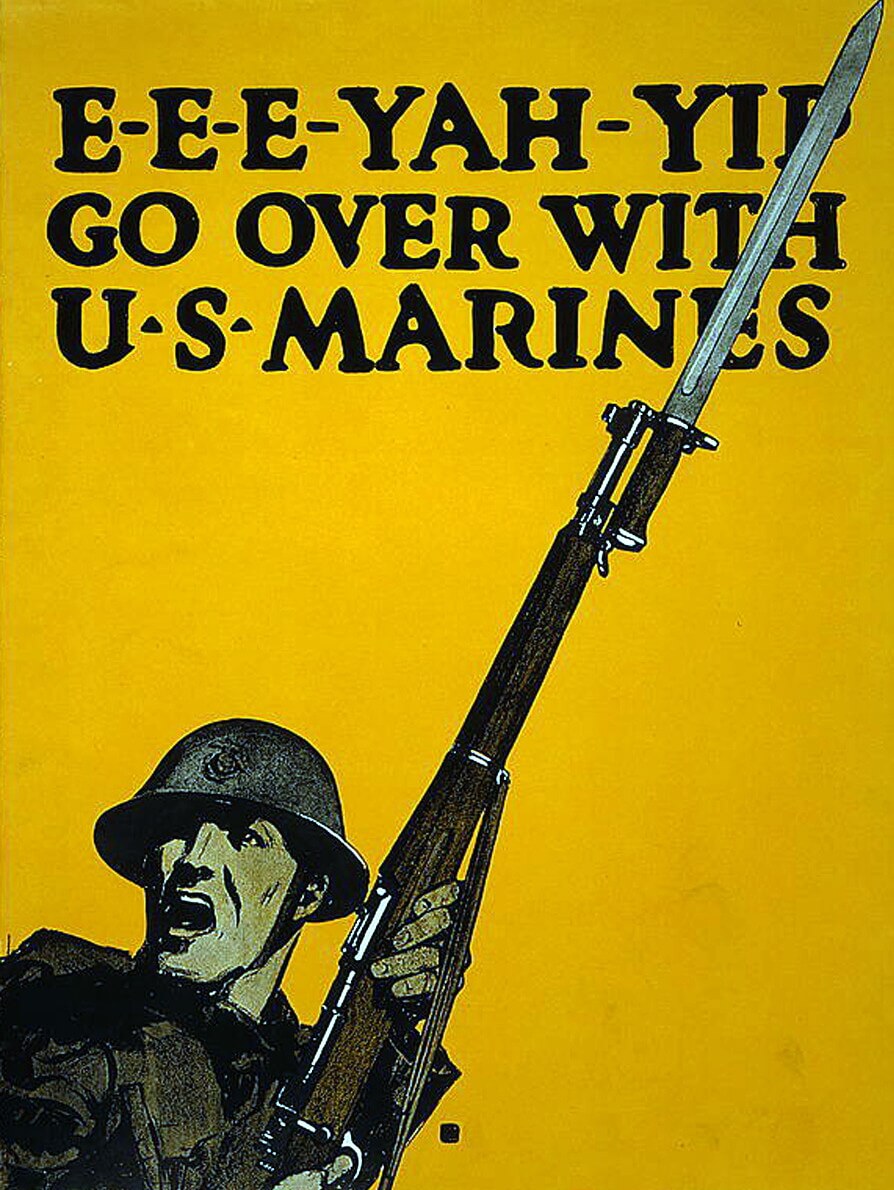

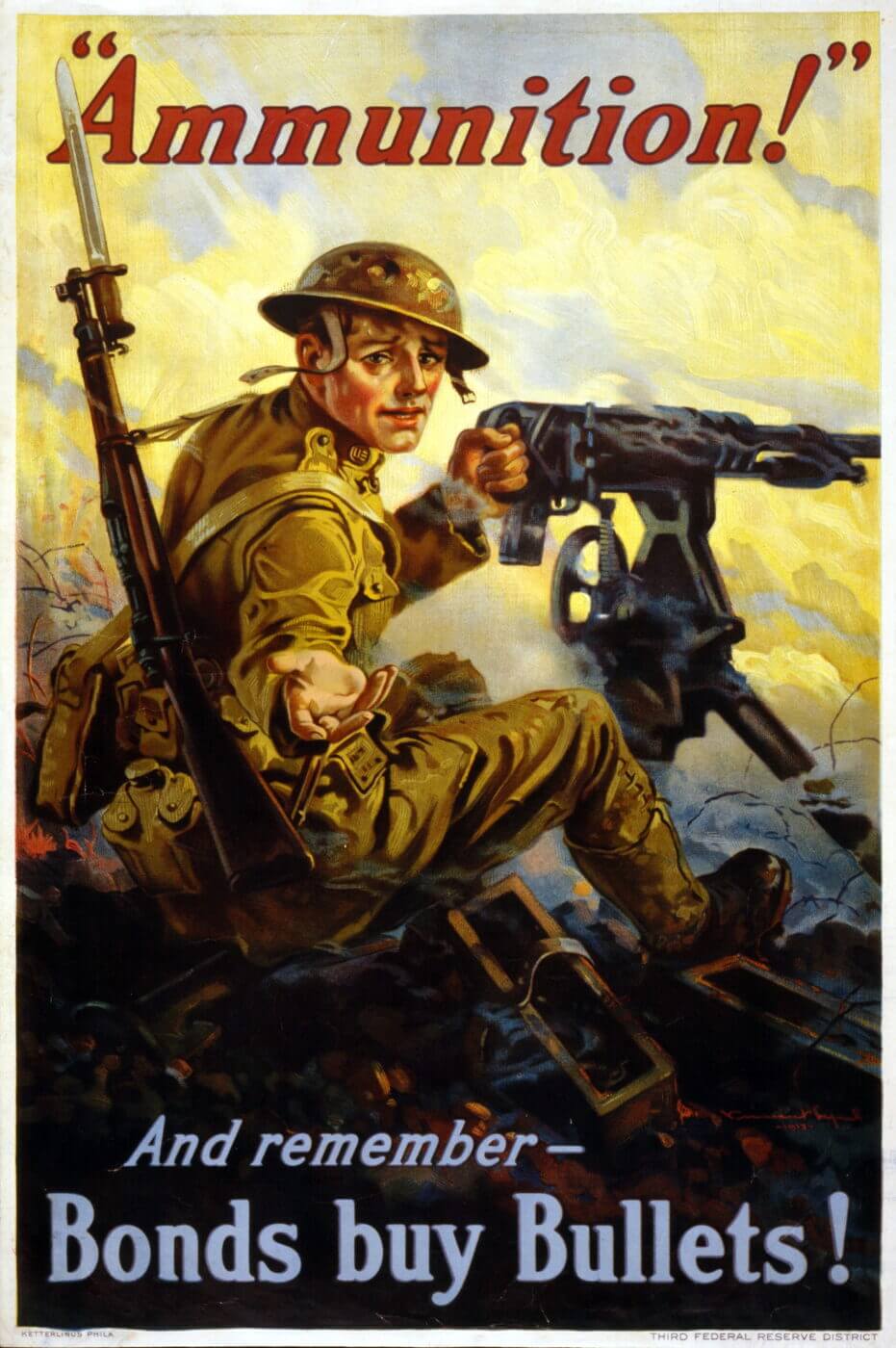

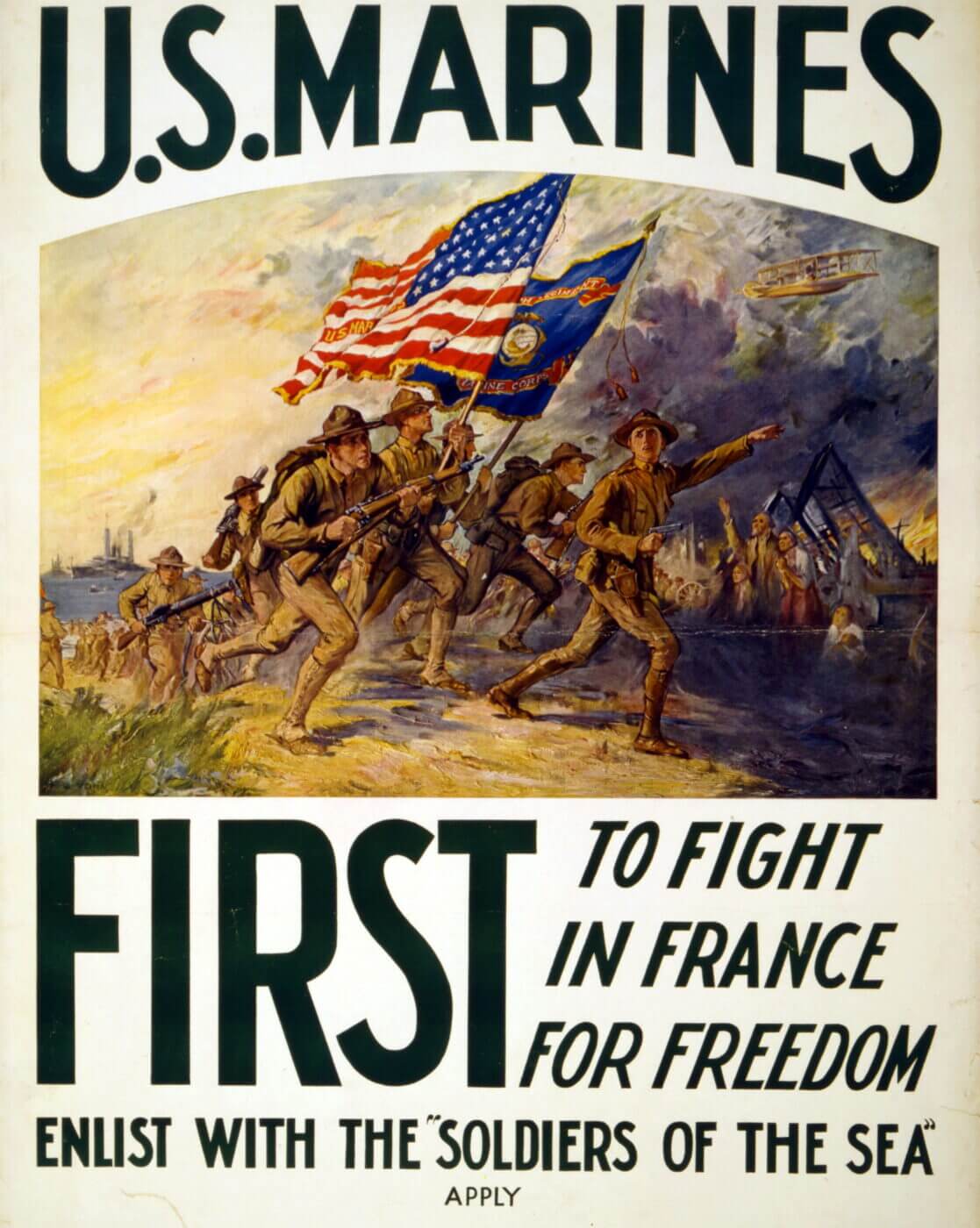

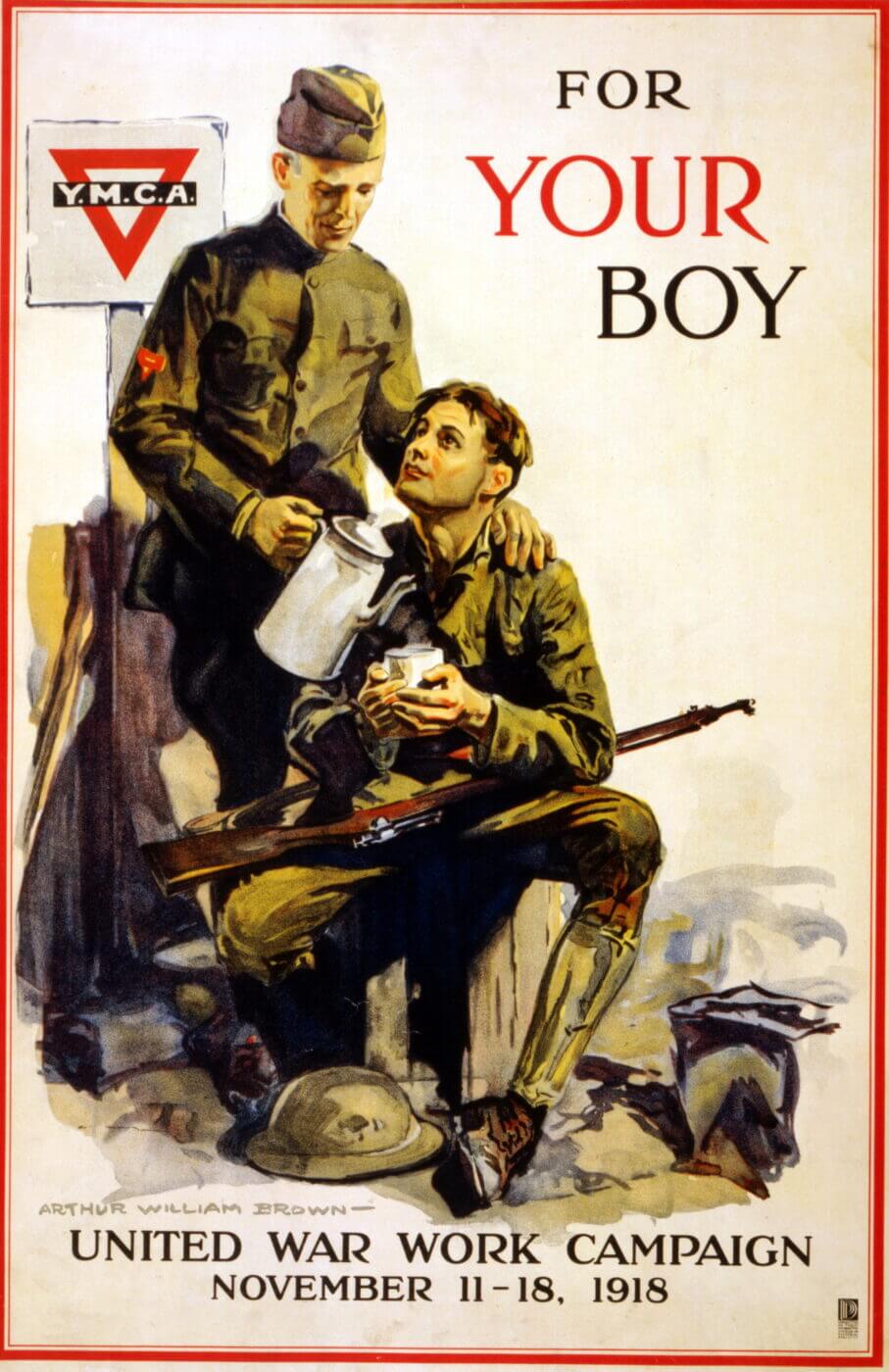

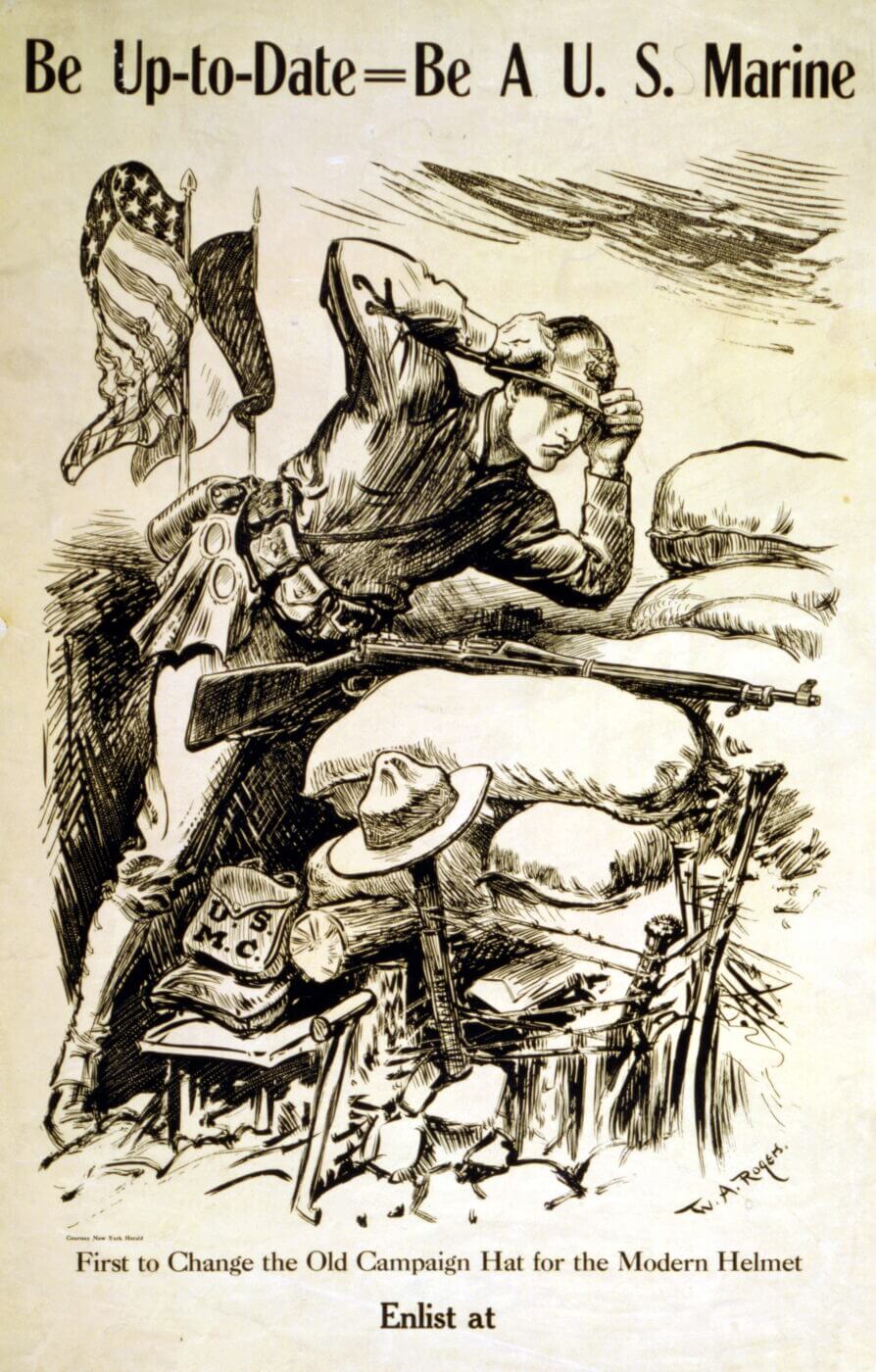

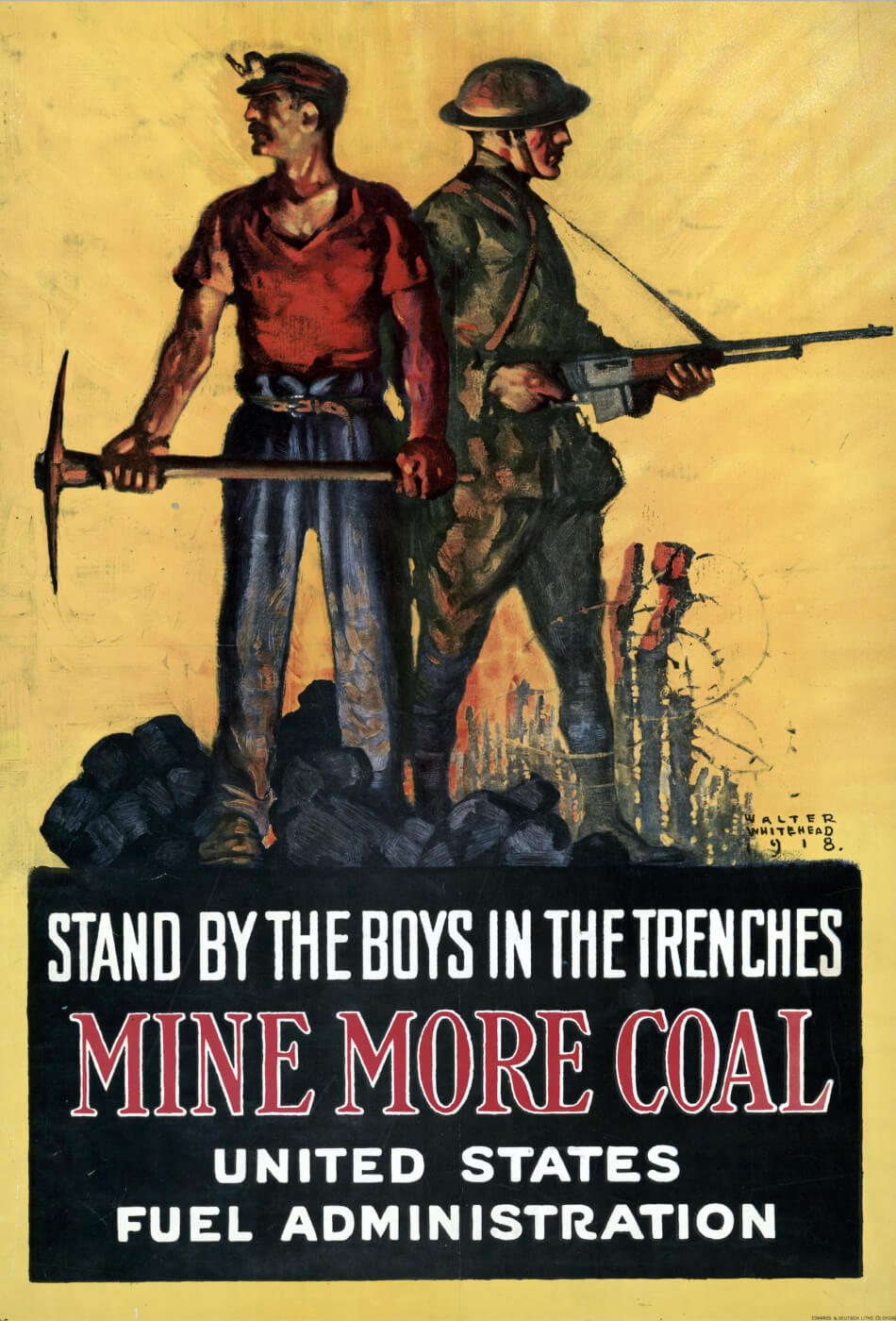

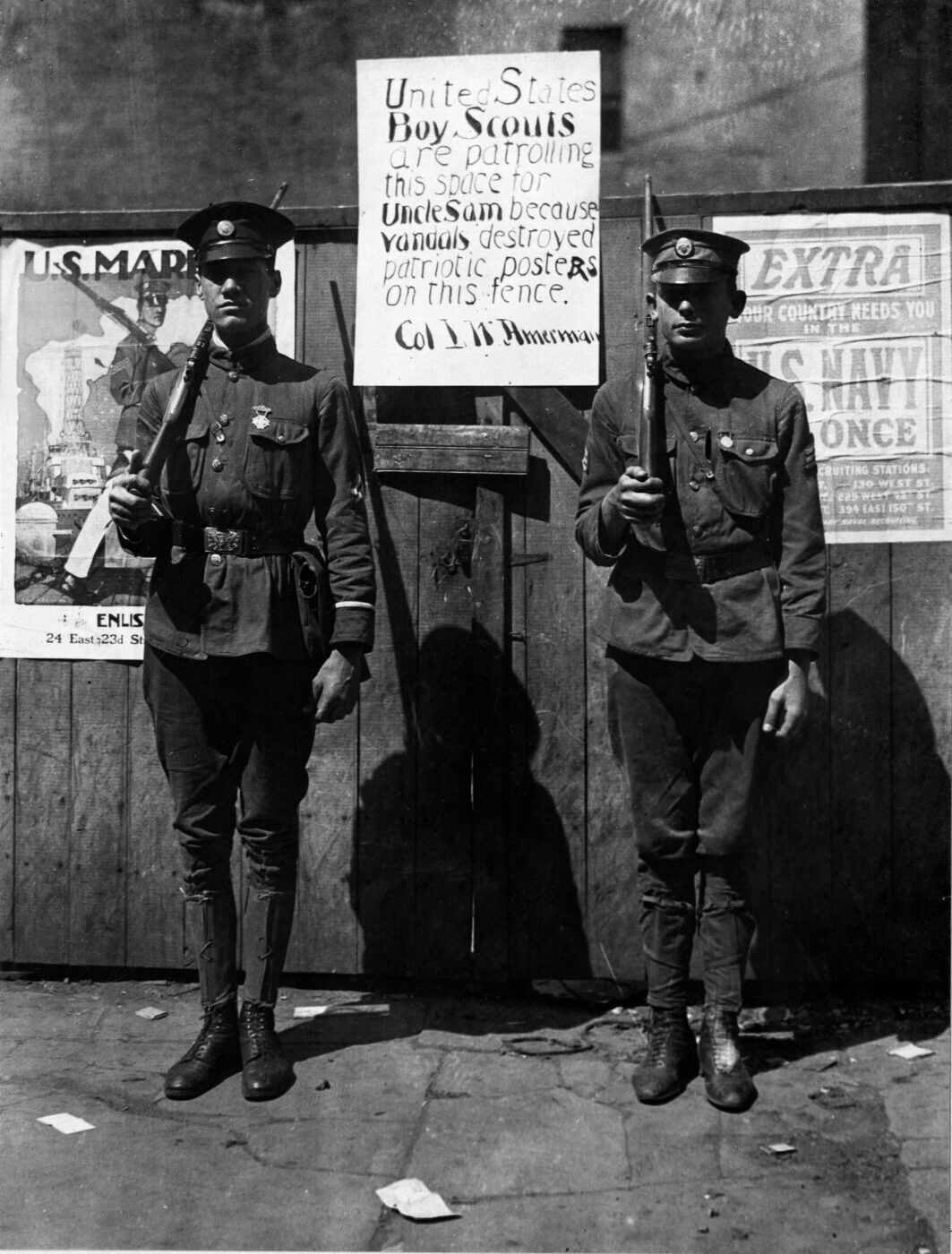

Once America eventually committed to join the Allies in 1917, the tone of the wartime posters began to change. Volunteerism and sacrifice were important subjects.

So too was the acceleration of war material production. During World War I, America would show strong indications of its growing industrial power and foreshadow the creation of “The Arsenal of Democracy” in World War II.

During 1918, poster art displayed the symbols of American pride and the products of American ingenuity and technology. Many of the great firearms that U.S. troops carried during World War I became iconic images and enduring symbols of America’s growing military might.

America’s diverse arsenal of small arms was featured in motivational, Liberty bond and recruiting posters: the M1903 rifle was often the star, as well as the M1911 pistol. Even though it would only appear in combat during the last months of the war, the .30-caliber Browning M1917 water-cooled machine gun was a regular part of the visual mix. Other weapons like the Lewis machine gun, the M1895 Colt-Browning machine gun and the Browning Automatic Rifle (to learn more about the BAR, click here) provided encouraging visuals to attract the attention of potential volunteers, or to build the morale on the home front.

As a result of America’s involvement in World War I, the Allied cause gained momentum and won the war against Germany. And, while this war was won, the seeds had been sown for another conflagration that would ignite a little over 20 years later. And once again, America would stand ready to help defend democracy.

Editor’s note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

85

85