Review: Springfield Armory 1911 Mil-Spec .45

June 9th, 2021

9 minute read

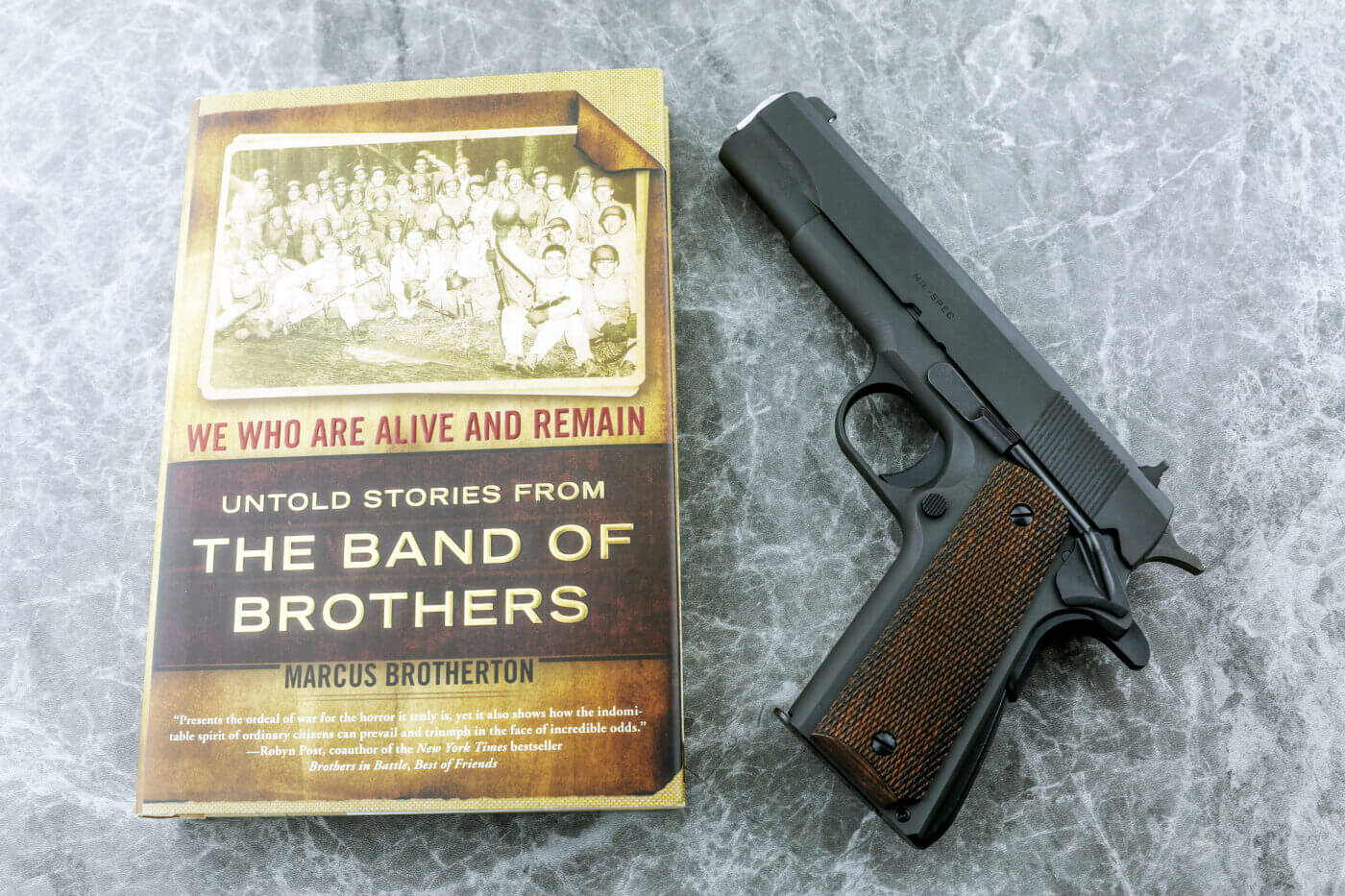

I recently had the chance to test the Springfield Armory Mil-Spec pistol in .45 ACP, positioned in the manufacturer’s line as a very reasonably priced basic service pistol — yet one that still features a rugged forged frame and slide. Except for its taller sights, it shares the silhouette of a World War II era 1911-A1.

While it’s part of the 1911-A1 series from Springfield Armory, curiously it is not so marked: the left side of the slide says simply MIL-SPEC, while the right side bears the Springfield Armory logo. So, exactly, what does “Mil-Spec” mean? In the case of this pistol, it can mean different things from different eras. The lines are sorta blurred…

Let’s review the Springfield 1911 Mil-Spec in further detail — describing what it is and how it performs as a .45 ACP pistol.

Original Mil-Spec

For the youngish among us who only see these pistols in history books and museums, a brief history of the 1911 is in order. John Moses Browning designed the gun that would eventually be adopted by the U.S. Military as the M1911. At its introduction in the eponymous year, the original 1911 had a flat mainspring housing on the lower rear of the frame, a long trigger, a short-tang grip safety, and a tiny blade of a front sight with an equally minuscule notch in the rear sight.

A century or so ago in the 1920s, our military ordnance people pragmatically decided that just in case what we now call World War I wasn’t “the war to end all wars” that folks were calling it then, it might be a good idea to look at upgrading the hardware for the next conflict. Surveys of doughboys who had used the “.45 automatic” in the trenches were conducted. As a result, several changes were made.

The results of those surveys led to recommended design changes, and the M1911-A1 was on the drawing board. It turned out that the hammer on the original 1911 was prone to pinch the web of the hand between it and the short grip tang. In fact, that stubby tang itself could draw blood upon recoil. So, the tang was lengthened for the 1911-A1 into the form that you see today on the Springfield Mil-Spec.

Those original Lilliputian sights were changed, too. They were squared off into a Patridge configuration and, while most of us today would still consider them to be too small, were a significant improvement at the time.

Rust resistance was also a concern. The original 1911 had a blued finish, and the 1911-A1 modification included corrosion-resistant Parkerizing. This gave it a distinctive and businesslike flat gray finish. This type of finish is present on the Springfield Armory 1911 Mil-Spec.

It was noted in both combat and on the range alike that bad shots tended to go low. Perhaps oblivious to the fact that training with weak stances (standing erect or even leaning slightly backward, firing with one hand only and shooting with little to no hearing protection) might be causing “trigger jerk,” U.S. Ordnance looked for a mechanical fix.

What they came up with was the arched magazine housing, shaped like an elongated half-teardrop that pushed against the heel of the hand and cammed the muzzle up. This would remain a standard 1911-A1 feature throughout military production and even on commercial Colts except the target models. This is present on the Springfield Mil-Spec.

One of the biggest complaints of World War I vets was that the trigger of the 1911 was too long and consequently harder to pull effectively. Thanks to better nourishment and prenatal care, American men are significantly taller today than they were a hundred years ago, and hands proportionally larger. If the average doughboy then stood maybe 5’ 6”, then half of them would be shorter with even shorter fingers.

Accordingly, the 1911-A1 redesign incorporated two features intended to correct or at least ameliorate the trigger issue. One was to machine recesses in the frame at the rear of both sides of the trigger guard, a feature which exists today on virtually every modern 1911 (except those intentionally marketed for nostalgic collectors of the earliest style).

But the other change was simply shortening the trigger. This was a boon for shorter-fingered soldiers, of course. But it had two more advantages. It made the 1911-A1 trigger configuration ideal for the hand of a petite female, whose fingers tend to be about one digit shorter than those of an average size adult male. Also, it allowed those of us with “average adult male hands” to get our index finger deep enough into the guard to contact the trigger at the distal joint, which can greatly increase the finger’s leverage on the trigger.

Modern-Spec

Now, specifically as to our test gun: It also has features from another “spec,” the sort of specifications that Delta Force insisted on for their custom 1911s used in special warfare and hostage rescue work. Let’s call that “modern spec.”

While the 1911-A1 kept the same small ejection port as the original 1911, modern shooters, beginning in the mid-20th century, demanded larger exit portals. The original design tended to dent ejected brass and was so small that sometimes when unloading the gun, a live round would fail to clear the ejection port and go trundling down inside the magazine well and out the butt, or worse, get stuck in the port.

I am happy to say the current Springfield 1911 Mil-Spec has the larger ejection port that we want in modern times, which solves all the above-mentioned problems and is standard in Springfield Armory’s whole 1911 line.

In addition, modern serious shooters want a magazine well that is at least slightly beveled for faster, more positive magazine insertion in emergencies. The 1911 Mil-Spec has that.

Also from what we might call “modern spec” are the big, easy-to-see fixed sights. The rear is shaped so that it can be run against belt or holster to rack the slide one-handed if a wounded warrior needs that. Mainly, though, the big sights are easier to catch under stress, easier to align precisely, and, well, all good and no bad. Springfield was wise to include these on the Mil-Spec.

Shooting the Mil-Spec

The easy reach to the short trigger found a pull weight that averaged 4.68 lbs. on a Lyman digital trigger gauge from Brownell’s. It felt lighter because the short trigger let me get my index finger all the way to the distal joint on the trigger face, giving me more leverage for the straight back pull. There’s a very short, light take-up followed by a short, sweet roll back and a very clean break. Of course, the beloved quick trigger reset common to the 1911 design is present here as well.

From a 6′ male to a 5′ female, everyone on our test team liked the gun. We all found it controllable, just like any properly held and shot 1911 .45.

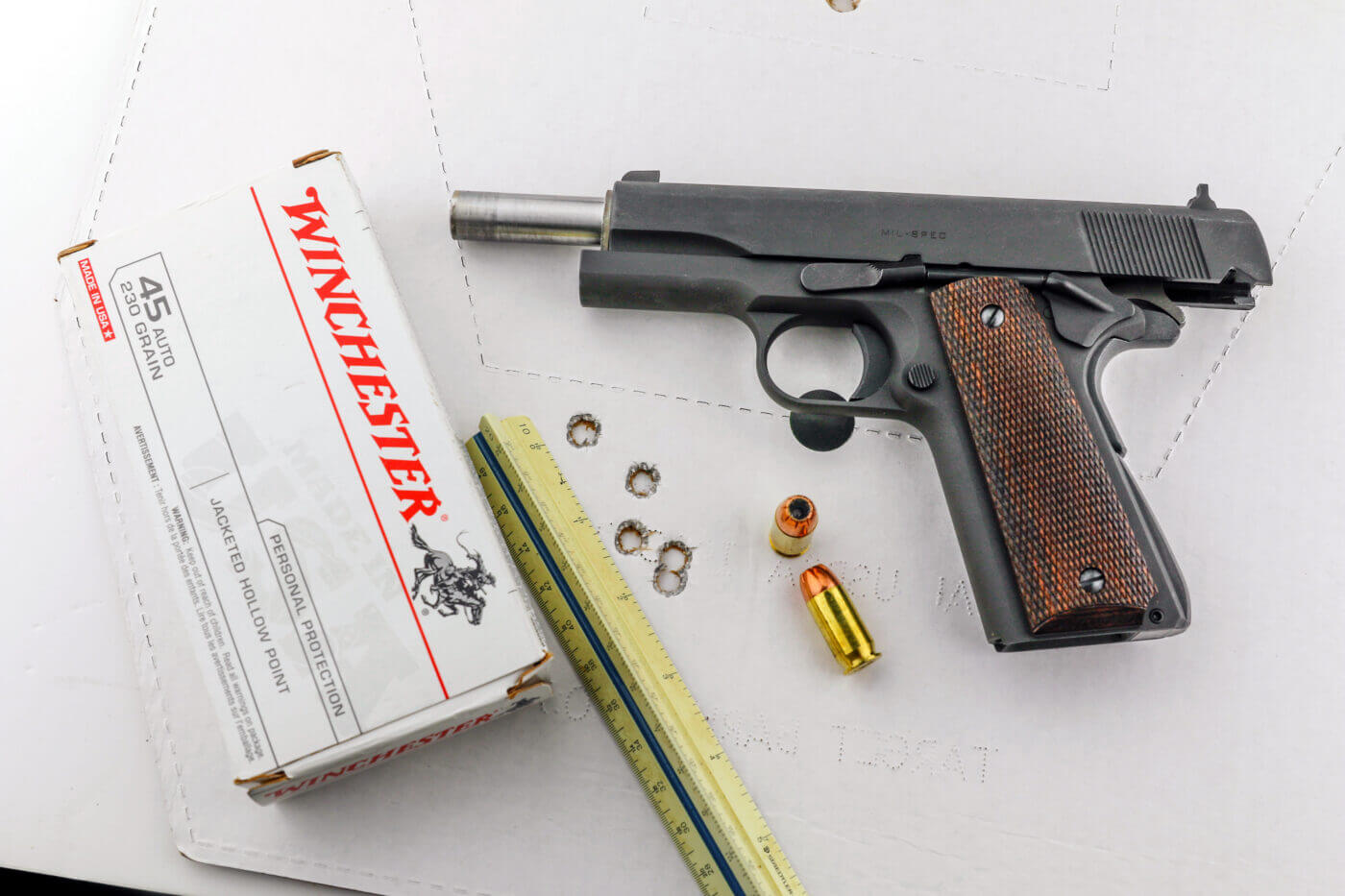

For accuracy, we tested from a Caldwell Matrix rest on a concrete bench 25 yds. from the target. Each five-shot group was measured to the nearest 0.05”, and twice: once overall and once for the tightest three hits. I’ve found over the decades that in experienced hands with no called flyers, that three-shot measurement generally approximates what the same handgun will do for all five with the same ammo from a machine rest.

We tested with three brands of ammo in the three most popular .45 ACP bullet weights. Remington 185 grain is the one jacketed hollowpoint most likely to feed in true “mil-spec” 1911s designed for full metal jacket round nose ammo. From the test 1911 Mil-Spec, serial number NM665381, it punched five holes in 2.75” measured center to center. The best three were in a cluster barely more than half that, at 1.40”. Think of the five-shot group as what an experienced shooter can expect from self-and-gun under ideal conditions, and the three-shot group as an indicator of the handgun’s own inherent mechanical accuracy.

Truly, 230-gr. ammo is the “natural food” of the .45 ACP, and by far the most popular bullet weight. Winchester’s relatively inexpensive standard jacketed hollowpoint expands surprisingly well out of a 5″ barrel such as the Mil-Spec’s stainless steel sample. The combination gave us a five-shot group measuring exactly 2.00”, and our tightest “best three” of the test coming in at a mere 0.65”.

The “just right Mother Bear” load of the day was the middle-ground bullet weight: Black Hills’ 200-gr. lead semi-wadcutter. It cut a contiguous curved line of big, clean bullet holes for a 1.65” group, the best three of which were in a tight 0.65”.

For a basic .45 ACP service pistol, that will most assuredly do. Judging by the “best three” groups, its accuracy potential lives up to the “NM” prefix on its serial number, which stands for “National Match.”

The Incredible Price

The price of an “economy gun” is seen as its raison d’etre, but we have to consider another price: the lack of some features on upper-scale models by the same manufacturer. On the Mil-Spec, I was pleased by the good “street trigger” and inherent accuracy, but I did notice some sharp edges on the hammer when carrying concealed in an excellent Kydex scabbard by Precision Holsters.

While the grip tang never bit any of us, I and the rest of the test team still much prefer the beavertail grip safety found on higher end Springfield 1911s. For one thing, their recurved tip helps to guide the drawing hand onto the gun faster and more smoothly when quick access becomes necessary.

In fairness, one advantage of the 1911-A1 grip tang configuration is that for those of us who prefer to holster a cocked-and-locked autopistol with thumb on hammer for additional safety, it’s easier and less awkward to do that with this old-style tang than with the beavertail.

Also, while the single-sided thumb safety was positive, it was stiffer than we wanted for quick on-safing one-handed. That said, I would expect that to “break in” with time and dry practice.

We experienced a single malfunction, a 12 o’clock misfeed with the lead semi-wadcutter rounds when administratively loading. However, neither that load nor anything else ever malfunctioned in any way during the firing cycle.

Springfield 1911 Mil-Spec Specifications

| Chambering | .45 ACP |

| Barrel | 5″ |

| Weight | 39 oz. |

| Overall Length | 8.6″ |

| Sights | Three-dot |

| Grips | Wood, checkered |

| Action | Semi-auto |

| Finish | Parkerized |

| Capacity | 7+1 (one) |

| MSRP | $640 |

At the price of only $640, some people ask where Springfield Armory builds these pistols. The Springfield 1911 is proudly made in the U.S.A.

Conclusion

While it won’t replace my Range Officer and Ronin models for carry nor my TGO-II for competition, the Springfield Armory Mil-Spec starting at $640 is an excellent value for the shooter dipping his or her toe in the 1911 pond, or looking for a classic battle-proven .45 design for personal or home defense.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

637

637