Rifle Scopes: Terms You Need to Know

October 5th, 2020

6 minute read

Refinements and features over the last 50 years have re-made rifle scopes. You’re smart to bone up on optics jargon before buying sophistication you won’t use — or that can even work against you! So let’s dive in and discuss some of the top features of a scope and explain what they mean — and why you should care.

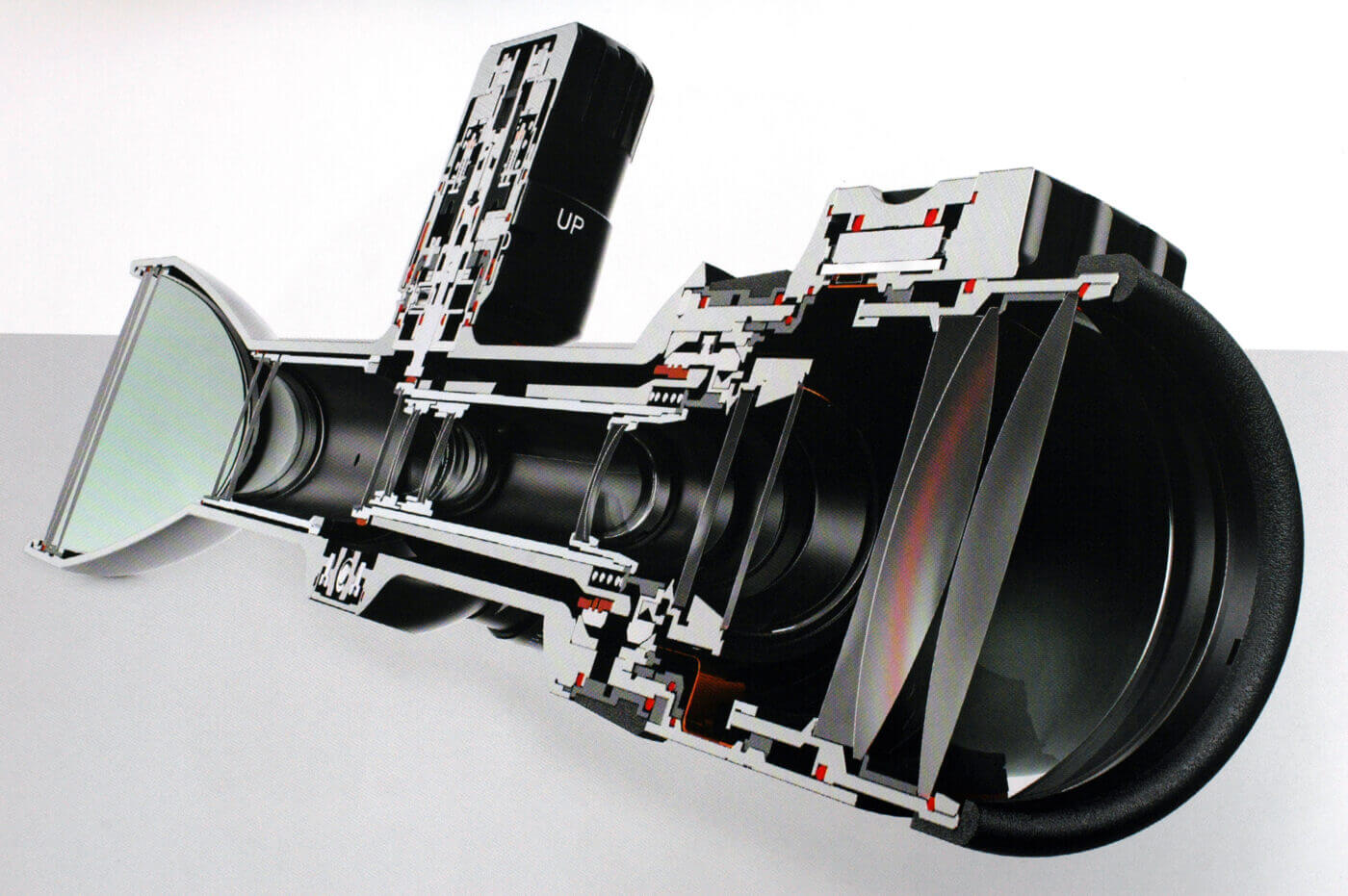

Fully Multi-Coated Lenses: You’ll want ’em! Reflection and refraction can pilfer four percent of light from each uncoated lens surface in a scope! Magnesium fluoride coating mitigated that loss in the 1930s. Now, multiple compounds pass a spectrum of wavelengths. “Fully” means all lenses, inside and out. You can’t tell by looking, but coatings impart color: straw to green and purple. New exterior lenses coatings slip or bead water — Zeiss’s LotuTec for example. Leupold’s Diamondcoat protects glass from scratches.

Resettable W/E (windage/elevation) Dials and Zero Stops: These speed your return to zero after dialing. A rotation indicator prevents full-rotation error when grabbing handfuls of clicks. These features benefit competitive shooters more than hunters.

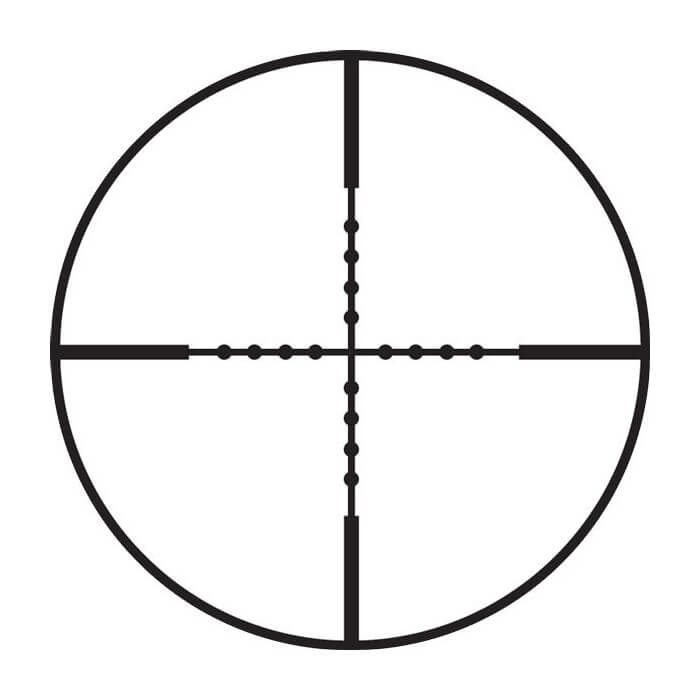

Mil-Dots: A mil (for milliradian) is an angular measure spanning 3.6 inches at 100 yards; a .1-mil “click” moves impact 1 cm there. A mil-dot reticle, with dots a mil apart on a crosswire, helps you find the range in yards. To do this, divide the target height in mils at 100 yards by the number of spaces it subtends. If a deer three feet at the withers appears two dots high (10/2 = 5), it’s 500 yards off. You can also divide target size in yards by the mils subtended, then multiply by 1,000: 1/2 x 1,000 = 500.

Parallax Correction: A reticle meets a focused target image at just one target distance. Ordinary hunting scopes are set for sharp focus and zero parallax at 150 yards. At other distances, if you move your eye off the scope’s axis, parallax will shift the target behind the reticle. AO (adjustable objective) collars and now turret dials let you hone focus and nix parallax error at all ranges. With your eye on the scope’s optical axis, however, there’s no parallax error to correct. For more information, please read my article where I describe what scope parallax is in greater detail.

Fast-Focus Eyepiece: Rotating the eyepiece focuses the reticle to your eye, independent of target focus or distance.

Power Range: Variable scopes became popular in the 1960s. They had 3X power ranges (top magnification three times the bottom). Now 6X, even 8X and higher ranges tempt shooters. But most competition rewards a narrow range of high power. Hunters with scopes set above 4X or 6X have lost chances at game they couldn’t find in the tight field. However, if you foresee needing to do shooting at a wide range of distances, a broad power range might be a good choice.

Big Objective Lenses: Boosting magnification reduces exit pupil, the diameter of the shaft of light reaching your eye. To calculate exit pupil (EP), divide objective lens diameter in millimeters by magnification. Your healthy eye dilates to about 7mm at night. A 6X scope with 42mm front glass has a 7mm EP. But you don’t shoot in the dark. In daylight, if your pupil contracts to 3mm, then opens to 6mm at dusk, the biggest EP it can use is 3mm, then 6mm — easy to get with small lenses at 4X, even 6X. Front lens size doesn’t affect field.

Big scope tubes: The 7/8″ tube of the 1940s grew to 1″, then 30mm, upstaged now by 34, 36 even 40mm pipes! Long-range shooters accept the added weight, bulk and expense of such scopes for greater elevation adjustment. Enhanced resolution from bigger erector glass can be hard to detect. If you don’t need the benefits, don’t add on the bulk and weight.

Trajectory-matched dials: Each custom-cut and scribed for a specific load, these let you “dial to the distance.” Laser the range at 500 yards, spin the dial to “5,” hold center and fire. Once an after-market option, a TMD for your load is now offered with some scopes at purchase.

Illuminated reticles: Lighted reticles help aim at a target in dim or low light. Usually only found in more expensive optics.

First vs. Second Focal Plane: Most scopes sold stateside have the reticle in the rear (second) focal plane, so it appears one size across the power range. First-plane reticles, popular in Europe, are gaining traction. They follow power changes. (To learn more about first versus second focal plane scopes, click here.) Extremely thin at low magnification, they bulk up at high power. But because they stay one size relative to the target, first-plane reticles make ranging easy at any magnification. So, if you foresee needing to do on-the-fly ranging with your optic and want to do it quickly, first focal plane might be a good choice.

Field of View: Commonly given in linear feet at 100 yards, field of view is better measured as an area formed by a cone. Areas of circles are proportionate to the squares of their diameters. A scope’s 200-yard FOV is four times the area of its 100-yard field. Magnification affects FOV, as do ocular lens diameter and eye relief (ER). A “cone of view” extends from your pupil to the lens perimeter. Say that cone’s angle is 24 degrees, the scope a 6X. Actual field is the cone’s span at any given range divided by the power. A 24-degree angle at 100 yards spans about 120 feet: 120/6 = 20 feet. To grow that field, you could trim power to 4x: 120/4 = 30 feet. Or you could make the ocular lens bigger, or reduce ER for a wider cone angle. A 30-degree cone would yield a 25-foot field at 6X, a 37 ½-foot field at 4X. Increasing ER shrinks FOV.

Scope Mounts: Consider the mount. Big objectives require high rings. Heavy scopes strain mounts and can slip in rings on hard-kicking rifles. Mass high over the rifle impairs handling. Ironically, many big, heavy scopes have little free tube, limiting options for ring placement.

Conclusion

The subject of rifle scopes can be confusing if you are new to the subject. However, with a little research and some guides like this piece here, you’ll be ready to dive in and make your choice for what you need. Once you make the move, you’ll be happy you did!

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

71

71