Stopping the U-234: Hitler’s Atom Bomb Submarine

January 25th, 2022

8 minute read

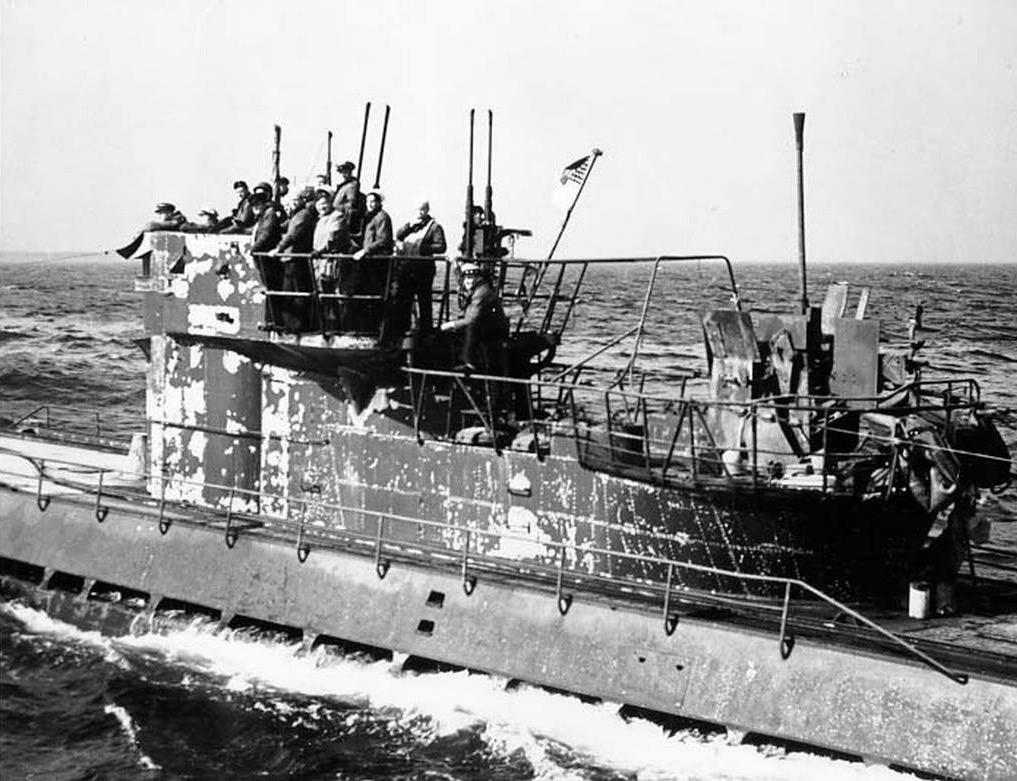

U-234 was on a mysterious mission. A Type XB U-boat, it was a large sub (1,735 tons surfaced and 2,143 tons submerged) originally designed to be a minelayer. She was quietly reconfigured as a long-range transport sub, and on April 15, 1945, she sailed from Kristiansand in Norway, bound for Japan with a strange group of passengers, and a cargo that contained items kept secret even from her Captain. It was the first, and last mission that the U-234 would ever undertake.

By this point in the war, Allied anti-submarine measures had become quite effective. Consequently, the U-boat had been fitted with the latest snorkel equipment, allowing the sub to travel submerged at a shallow depth while still drawing in fresh air and running on their diesel engines. Speed was restricted to six knots, however, to prevent damage to the snorkel tube. U-234 spent the first 16 days of the journey underwater before rising to run on the surface for two hours each night under the cover of a severe storm.

In Germany, the Reich was collapsing, and the Kriegsmarine’s primary transmitters went off the air. Even while he considered the silence to be strange, U-234’s commander, Kapitänleutnant Johann-Heinrich Fehler, did not know that his navy’s headquarters had fallen.

On May 4th, U-234 intercepted part of an Allied broadcast that announced Hitler’s death and that Admiral Karl Dönitz was now in overall command of Germany’s armed forces. On May 10th, Fehler surfaced and received Admiral Dönitz’s order that all U-boats must surrender to Allied forces. Even so, Fehler did not believe this transmission was legitimate and sought verification. He found this when he was able to contact another U-boat that confirmed Germany had surrendered.

The Race to America

The Battle of the Atlantic had raged from the first day to the last of the war in Europe. Along the way more than 72,000 Allied sailors and merchant seamen lost their lives on the 3,500 merchant vessels and 175 warships that were sunk. Many of these came from England and Canada during the long U-boat offensive.

Fehler discussed surrender with his crew. Some men favored a return to Germany. Others suggested a trip to neutral Argentina. One of those men was Lt. Karl Ernst Pfaff, who was engaged to Fehler’s sister-in-law. Ultimately, Fehler opted to go to America where he reckoned that his crew would receive the best treatment. Consequently, he ordered the sub to sail to Newport News, Virginia.

To confuse Allied forces and give himself more time, Fehler radioed on May 12th that he was sailing to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to surrender to Canadian authorities. As he closed on his real destination, Fehler threw his Tunis radar detector, the latest “Kurier” radio system, and any Enigma equipment and documents overboard.

Some important housekeeping duties immediately presented themselves. Among U-234’s twelve passengers were two Imperial Japanese Navy officers, Lt. Commander Hideo Tomonaga, a naval architect and sub designer, and Lt. Commander Shoji Genzo, an aviation expert. The Germans informed their Japanese passengers that they had been ordered to surrender and were in the process of doing so. After hearing this news, the Japanese officers committed suicide with an overdose of Luminal, a powerful sedative. Apparently, it was a painful death, and it took the Japanese 36 hours to die. The crew then buried them at sea.

Capture by the USS Sutton

The war diary of the USS Sutton (DE-771), Lt. Commander T.W. Mazro commanding, details the next stage of U-234’s journey.

May 14: At 2024 our radar picked up a target at 18000 yards proceeding on the U-boat’s course and speed. At 2141 overtook the target and identified her as U-234. Changed her course to 250 and escorted her for the rest of the night at eight knots.

Commander Mazro received a significant amount of information about U-234 in a short time:

Two Japanese officers who are reported to have killed themselves with Luminal when they heard of the U-boat’s intentions to surrender. Their bodies had been disposed of prior to capture.

As to U-234’s cargo, Mazro wrote: “She was reported to have a valuable cargo of war instruments, plans, and documents which were secured in the cargo hatches.”

Clearly, the Germans were relieved to be in the custody of the U.S. Navy:

At no time since their capture have the Germans on the Sutton or on the U-234 been anything but cooperative. Dr Walter (of the U-234) assisted the doctor of the PF 102 in a difficult abdominal operation on one of the Sutton’s men.

News of the big U-boat’s capture attracted the attention of the media, and many reporters came to Portsmouth, New Hampshire to see U-234, and others, brought in. Some even chartered a small boat to go to sea and watch them come in under guard.

U-234’s Cargo

U-234 carried a cargo load that weighed 240 tons along with enough diesel fuel and supplies for a voyage that could last more than six months. U.S. Naval ordnance experts began to dissect the submarine’s cargo and discovered examples of the latest German electric torpedoes, a disassembled Messerschmidt 262 jet fighter, a Henschel Hs 293 glide bomb, and a technical treasure trove of technical drawings and documentation. Inside the sub’s mine shafts they also found 50 nine-inch-long lead cubes, each marked “U-235”. Most of the original investigators would never know that this was Uranium Oxide.

Many of U-234’s officers were taken to Quantico, Virginia for interrogation. Second Officer Pfaff later wrote that he was taken to an undisclosed location in Virginia where much of the cargo from U-234 was stored. Pfaff claims that he was designated to guide the opening of one of the lead containers, which the American troops suspected were booby-trapped.

Pfaff told his captors: “Why would these boxes be booby trapped? They were on their way to our ally — Japan. Why would we want to blow them up?” After the lead containers were safely opened, Pfaff claimed he saw a “skinny fellow wearing an Elliot Ness-style hat”. Pfaff was told that it was Oppenheimer, but he had no idea who the American nuclear physicist was.

The U.S. intelligence summary of May 19, 1945, listed a wide range of materials in U-234’s cargo, including documents, instruments, lead, mercury, optical glass and brass. But there was no mention of uranium. The uranium from U-234 “disappeared”, and most historians figure that it was added to the stocks of the Manhattan Project. After processing, it would have yielded about 20% of what was required to arm an atomic bomb. In the big picture of the intelligence war, the 1,200 pounds of uranium oxide carried aboard U-234 remained a secret until the end of the Cold War.

Japan’s Atomic Bomb Program

Many people don’t realize that both the Germans and the Japanese had active atomic weapons programs. Scientists in both Axis nations struggled with similar problems — gaining the attention, approval and financing of their governments, as well as acquiring a useful supply of uranium. In the end, the lack of uranium doomed both the German and Japanese atomic programs, but the effort was there until the very end.

The Manhattan Project Intelligence Group reported that Japan’s nuclear physicists were just as good as those from other combatant nations. There is no doubt they would have used an atomic weapon if they had developed one before the war ended.

Big Bombs, and Small Arms

While few of the American sailors or Marines knew the reality of U-234’s secret cargo, they understood full well the capabilities of the small arms they carried. While they captured and guarded the German U-Boat crews, they had all the firepower they needed.

Commonly found among the Navy men and Marine guards was the .45 caliber M1911 pistol. At short range, the M1911 had no equal, and the big handgun served America well in both world wars and continued to serve until the early 1990s.

Frequently seen in the hands of Navy, Coast Guard and stateside Marines is the Reising Model 50 submachine gun. The .45 caliber Reising was purchased to provide an early war replacement for the Thompson SMG, which was in short supply. The Marines used the Reising during early battles in the Solomon Islands and found the Model 50 (and folding stock Model 55) to be substandard in those harsh combat environments.

However, in the hands of the Navy and Coast Guard, the Reising proved a reliable supplement to the limited amount of Thompson SMGs in service on the high seas. The biggest drawback with the Reising was its small magazine capacity — topping out at just twenty rounds.

The Navy and Coast Guard made good use of the venerable M1903 Springfield rifle throughout the war. The Springfield was one of the finest military rifles ever produced, and U.S. naval marksmen left no doubt about its accuracy, sniping everything from floating mines, to sharks to the occasional opportunity to target a surfaced U-Boat. Both the Navy and Coast Guard carried various shotguns in their weapons lockers: the Winchester Model 97, Winchester Model 12, Ithaca Model 37 and the Stevens Model 520-30 all could be found in service along with multiple types of commercial shotguns. All were used for impromptu skeet shooting and occasional bird hunting as the opportunities presented themselves.

Conclusion

Thankfully, the cargo of U-234 never made it to its destination and was never developed into a weapon to be used against the Allies. Thanks to the war effort by America across two oceans, and the bravery of the sailors and Marines on the USS Sutton, Hitler’s atomic submarine was stopped.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

817

817