The 1911 in the Skies

December 31st, 2019

5 minute read

During the Great War, the “magnificent men in their flying machines” captured the public’s attention as they maneuvered their crude and fragile craft in the first era of aerial combat. Pilots became celebrated as the knights of the air, racking up impressive scores as they downed enemy aircraft behind chattering machine guns. Meanwhile, the unglamorous infantry battled it out among the mud, barbed wire, and trenches.

At normal combat ranges, rifles and machine guns ruled their world. In close combat, pistols, knives, and clubs did the dirty work. Great War pilots often carried pistols too, but rarely for combat. Their wood and canvass aircraft burned easily, and parachutes were not available until 1918 (and most Allied air forces never issued them). Pistols were carried aloft for the last resort, the unimaginable choice between a bullet to the head or burning to death or leaping from the cockpit for one very long fall.

Higher, Farther, and Faster

In 1918, the high-performance fighter in service with the U.S. Army Air Service was the SPAD S.XIII. Fast for its time, the SPAD’s top speed was 130 mph at 6,500 feet. It was armed with a pair of Vickers machine guns. When the United States entered World War II in December of 1941, its primary fighter was the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, an all metal, single-wing design that was capable of 334 mph at 15,000 feet. The Warhawk carried six .50 caliber Browning machine guns in its wings and could carry up to 2,000 pounds of bombs.

The pilot’s mission was essentially the same, but his tools were dramatically improved. The cockpit had advanced from a handful of switches and essential dials to an armored bathtub filled with the latest electronics, including a high-powered radio and oxygen equipment. Depending on the design and the size of the pilot, the space in the cockpit ranged from cramped to claustrophobic.

Combat in the Clouds

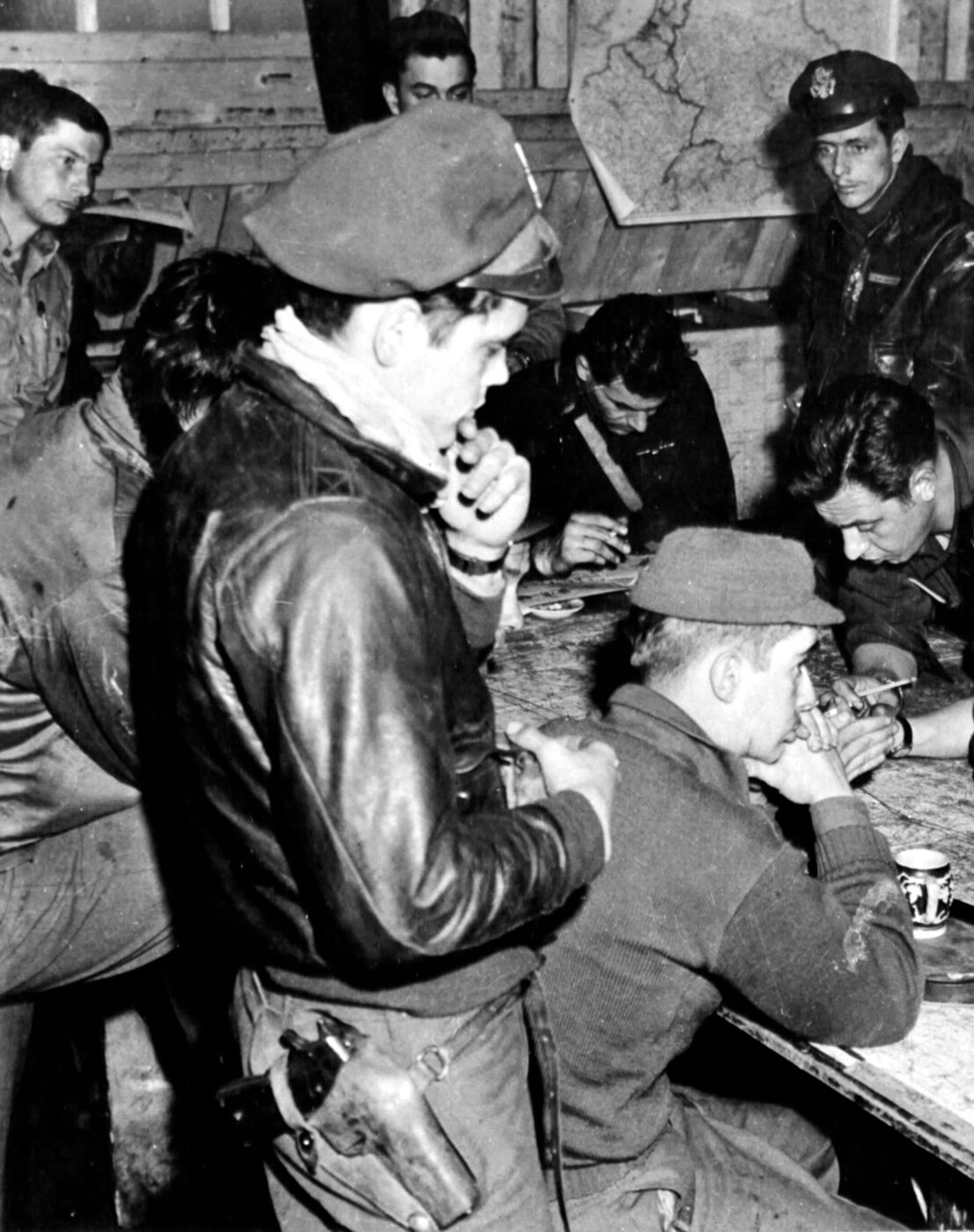

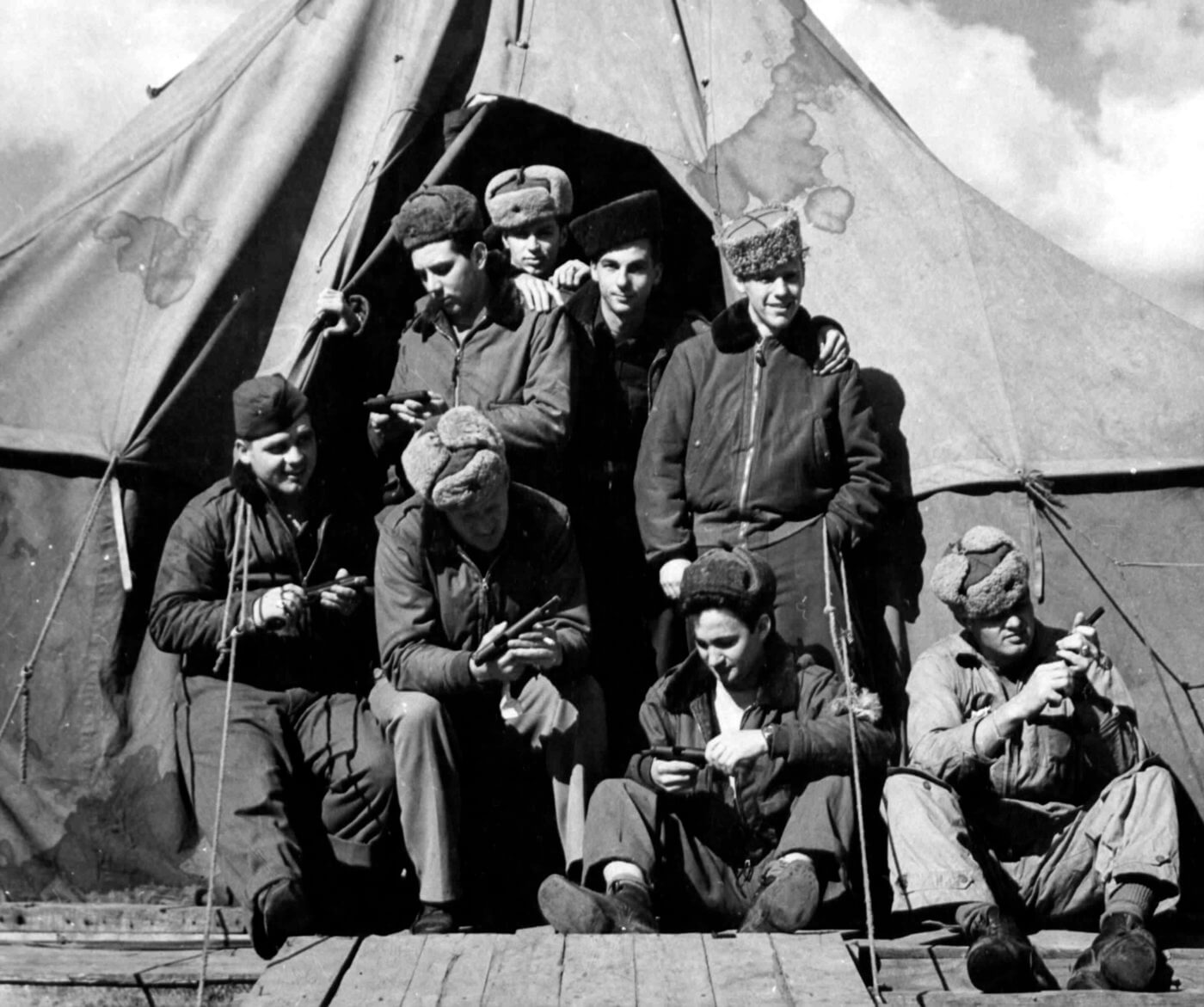

The U.S. Army Air Force was allocated a large number of M1911 pistols, but pilots and aircrew were not necessarily required to carry them. Ultimately, carrying a pistol on a mission became an issue of the prevailing conditions in the combat theatre, as well as the personal preference of the airman. The crew positions in certain aircraft (and for certain functions within it) proved to be too tight for the crewman to do his job while wearing a pistol and holster.

In the air war over Europe, only a small amount of the heavy bomber crews carried the M1911 aboard the heavy B-17 and B-24 bombers, or the medium B-25 and B-26 bombers. The crew positions on the light bombers/attack aircraft (A-20 and A-26) were generally too tight to accommodate the extra bulk of a pistol. Another key issue for bomber crews was that a pistol would likely cause them more trouble than it was worth if they were shot down over German territory. If brought down in Germany itself, some crews were attacked by German civilians with murderous intent after suffering the effects of repeated Allied air raids. A pistol might keep a crew safe from pitchfork-wielding townsfolk, only to see the airmen hanged by the German military for crimes against civilians.

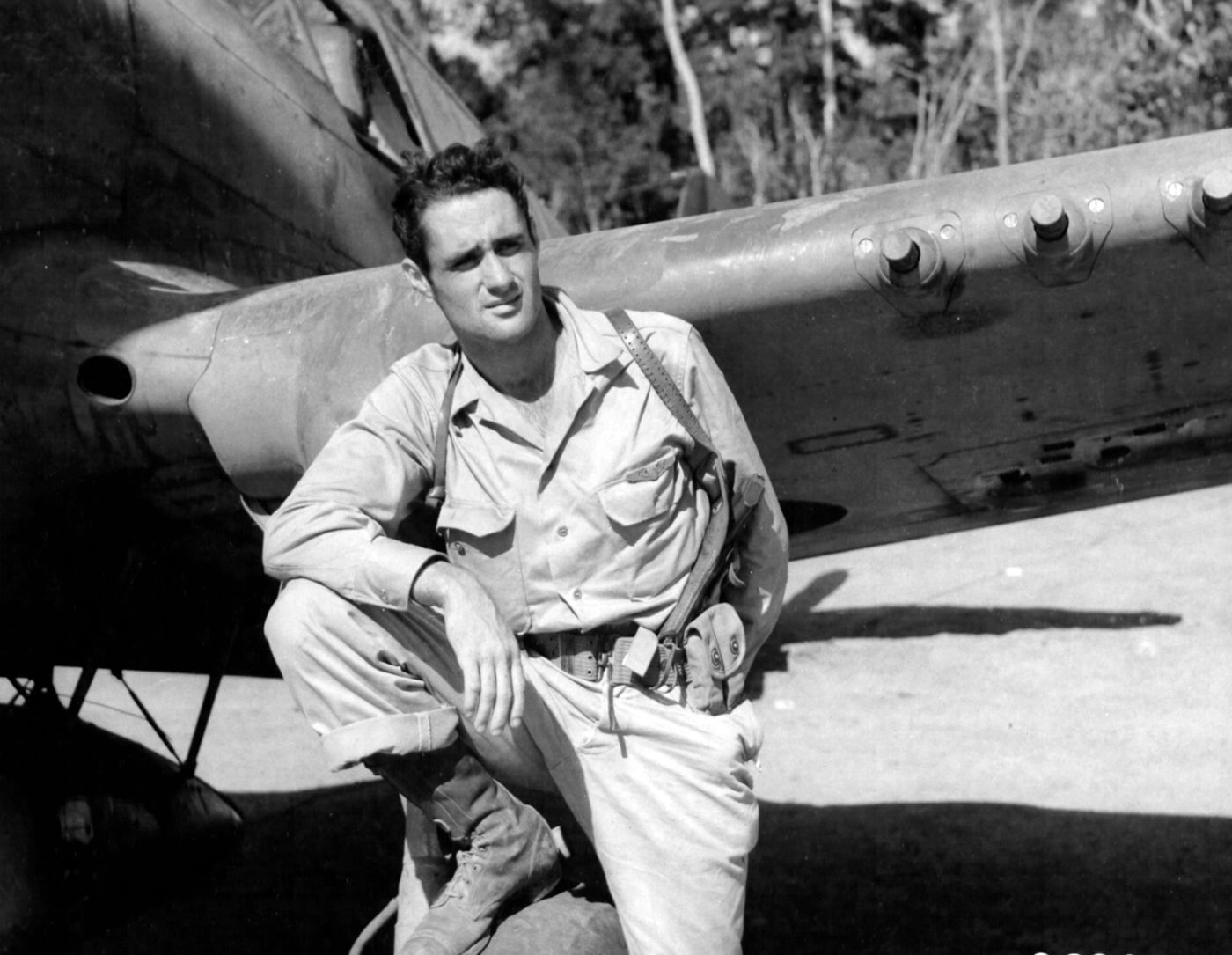

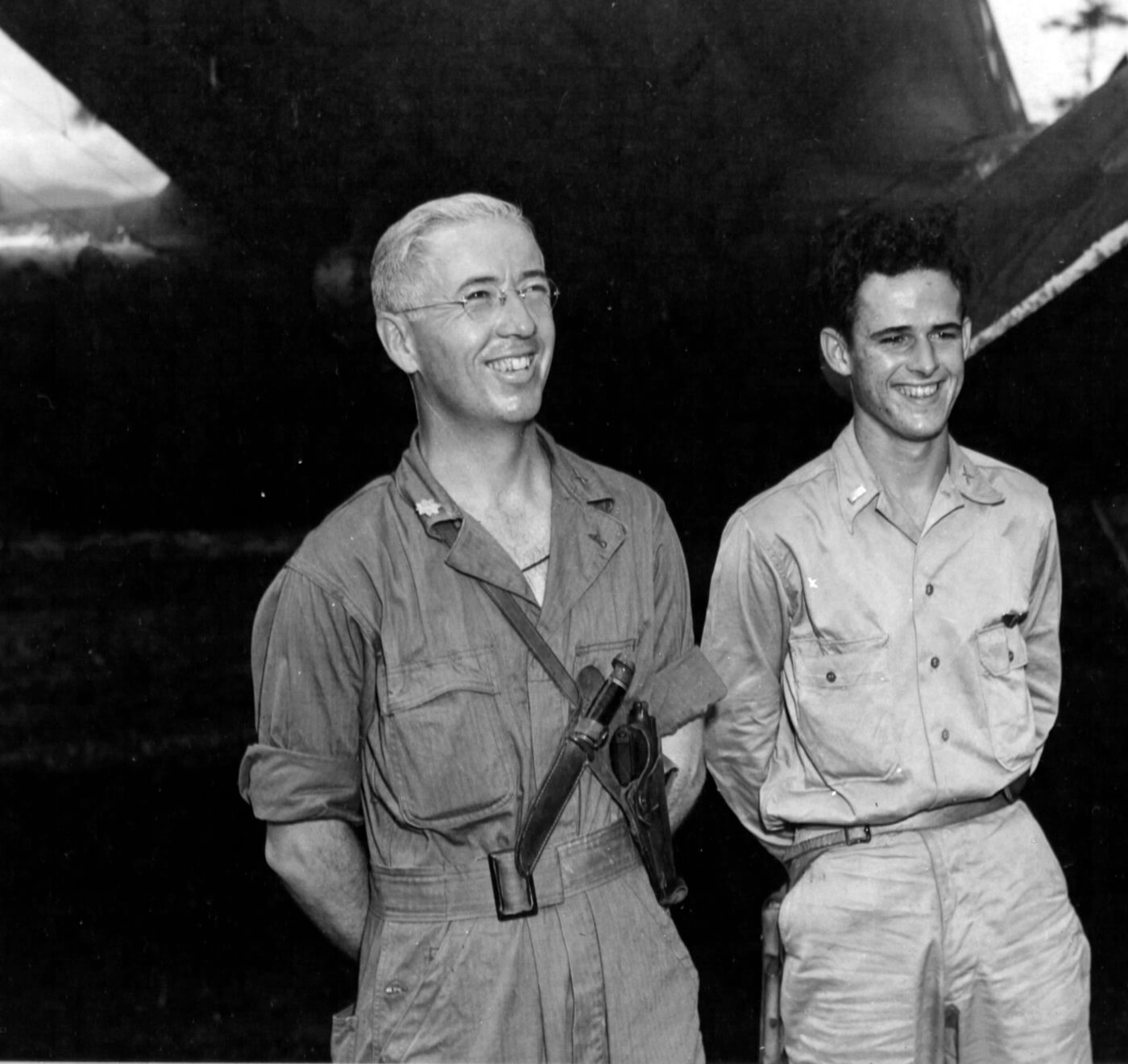

Most American fighter pilots flying air superiority missions over the ETO and MTO didn’t bother with carrying a pistol. However, while gathering wartime photos for this article I noticed a fair number of fighter-bomber pilots (mostly from P-47 Thunderbolt squadrons of the 9th Air Force based in France beginning a month or so after D-Day) carried the M1911, either on their hip or in a shoulder holster. Their ground attack missions were often carried out where the fighting was the thickest, and apparently some believed that the big pistol would give them enough cover until they could reach friendly troops.

The conditions were quite different in the Southwest Pacific and the China-Burma-India theatres. Downed pilots faced the dangers of the primeval jungle, where many of the indigenous animals and native tribes were both hostile and hungry. The Japanese were not keen on taking prisoners, and when they did American pilots often wished they hadn’t. Horrible though that choice may be, a M1911 gave a downed pilot or airman an option. He could always save the last bullet for himself.

Escape and evasion techniques, coupled with a resourceful and resolute American spirit, along with some judicious use of the M1911 ultimately saved many downed U.S. airmen. As for carrying a pistol in the tight confines of an aircraft in combat over enemy territory, I’m reminded of my father’s old axiom about firearms: “Better to have it and not need it, than to need it and not have it.”

Today’s Option

Now you can have your own 1911, courtesy of Springfield Armory’s Mil-Spec .45 ACP priced at just $549 MSRP. It handles like the government-issue M1911 that the American troops carried into battle by land, air, or sea during World War II, and has some modern upgrades like a stainless steel barrel and three-dot sights.

You’ll find every bit of the combat-tested toughness of the M1911 pistols that defended America built into this brand-new Springfield Armory 1911 pistol.

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

392

392