The Armory Life Interviews MACV-SOG’s Major John L. Plaster

September 28th, 2023

14 minute read

Editor’s Note: This interview ran as a cover story for the Summer 2023 issue of our print magazine. However, that version was edited down for length due to space constraints. Following is the full version of our interview with Major John L. Plaster, with additional details and information not included in the original print publication piece.

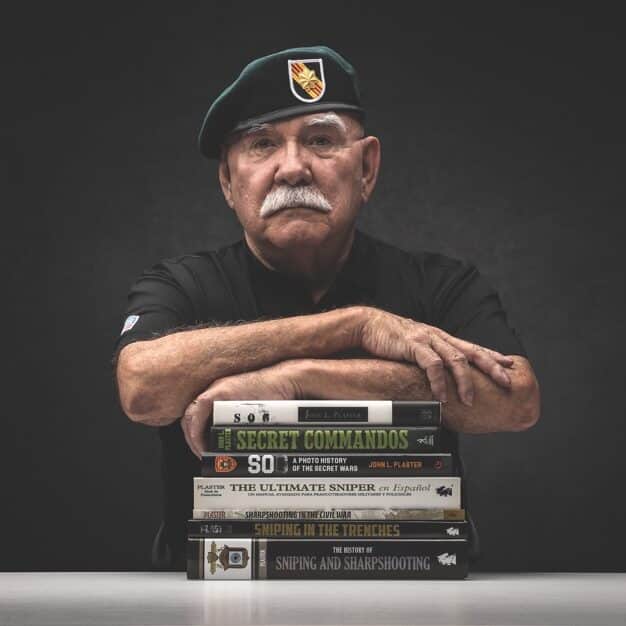

The Armory Life is honored to have recently interviewed Major John L. Plaster, retired U.S. Army Special Forces officer, renowned expert on all things sniping, and prolific author and longtime sniping instructor.

In the early part of his career, Major Plaster served three tours in Southeast Asia with the top-secret MACV-SOG (Military Assistance Command, Vietnam — Studies and Observations Group) clandestine operations unit. During this time, qualified as a paratrooper as well as a Green Beret weapons and communications NCO, he led missions deep behind enemy lines in Laos and Cambodia. After the war, his combat experience and expertise made him a highly respected sniper trainer for military and law enforcement agencies around the world. He’s an inductee into the U.S. Army Special Forces and the U.S. Air Force Air Commando Halls of Fame. In addition to his military background and knowledge, he is also a prolific writer on firearms, special operations and military history.

We would like to thank Major Plaster for taking the time to do this Q&A session with The Armory Life.

The Armory Life (TAL): Please tell us a bit about yourself, for those who might not be familiar with you and your background.

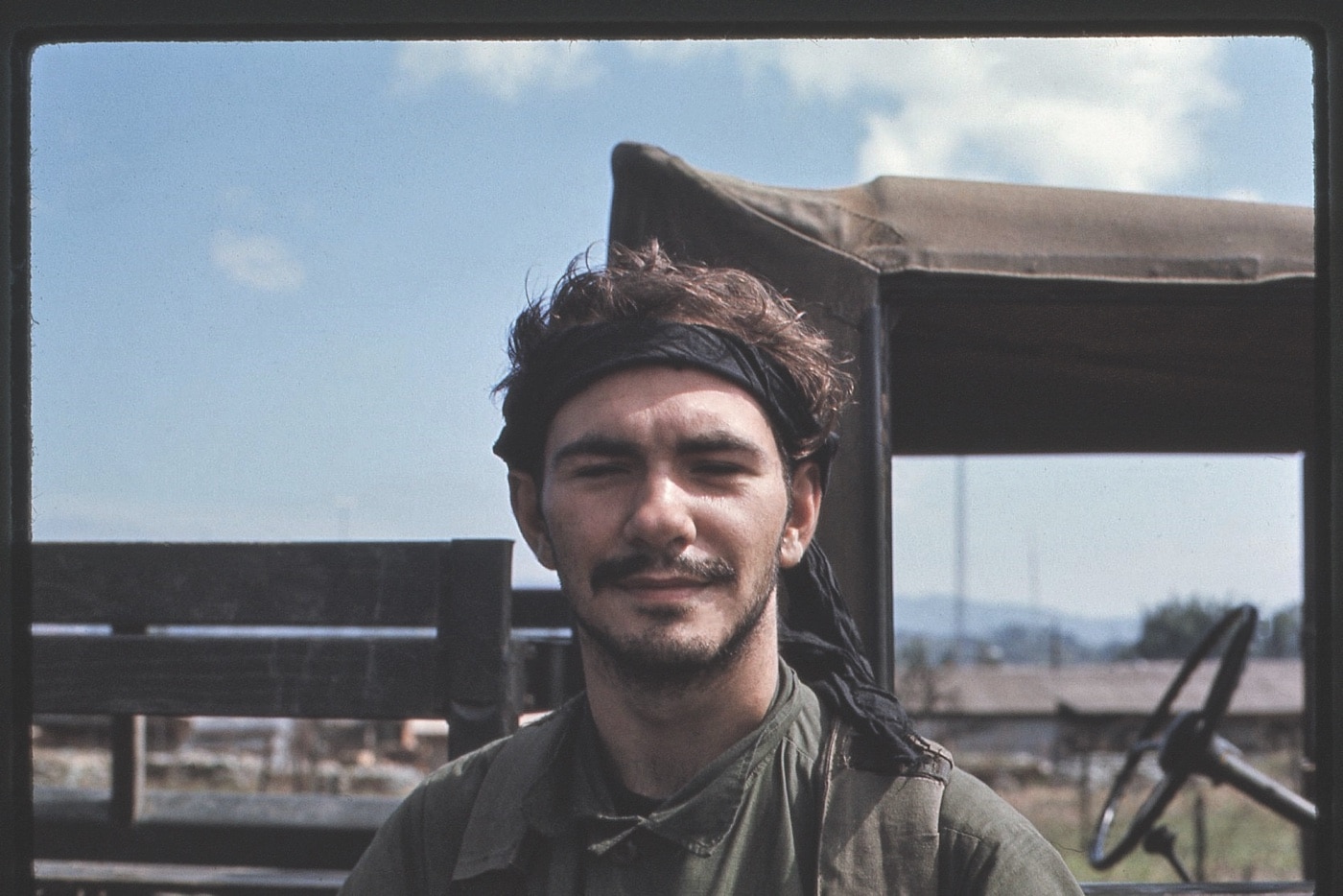

John Plaster (JP): I was a Green Beret staff sergeant during my years with SOG. After that, based upon my combat experience, I received a direct commission. In all, I served 11 years active duty, and 12 years in the Reserve components. During a break in service, I attended college and earned a degree in Journalism, which was mighty useful when I began writing in the early 1990s. My first book, “The Ultimate Sniper,” reflected two decades as a sniper instructor and commandant of the National Guard Sniper School. I’ve gone on to write seven more books, all related to sniping and special operations.

TAL: Many readers might be familiar with the MACV-SOG acronym, but unfamiliar with its meaning. Can you tell us some more about the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam — Studies and Observations Group?

JP: MACV-SOG was the cover name for the top-secret unit that conducted clandestine ops across Southeast Asia, primarily in Laos, Cambodia and North Vietnam. The existence of our operations was officially denied by the U.S. government and remained classified until the mid-1990s. G.I.s fighting in South Vietnam did not know what we were doing, but we believed we were supporting all of them by hitting the enemy in his own backyard.

Officially, those of us who volunteered for SOG were 5th Special Forces Group soldiers supposedly “training indigenous personnel.” As a Joint Unconventional Warfare Task Force, SOG included elements of all the services. Army Green Berets led the cross-border ops into Laos and Cambodia and (rarely) North Vietnam. Navy SEALs trained our indigenous “Sea Commandos” for seaborne raids into North Vietnam, as well as conducted their own ops in South Vietnam.

SOG had its own Air Force with squadrons of C-130s and C-123s for air-dropping agents into North Vietnam, as well as dropping our Green Beret HALO and static line parachute teams. We also had the war’s only USAF combat Huey unit and a squadron of South Vietnamese H-34 helicopters.

Our CIA civilian personnel conducted “Black Psyops.” That is, they confused the enemy with everything from counterfeit currency to forged documents, and, especially, booby-trapped ammo, which we planted on enemy bodies or inserted into ammunition stockpiles.

TAL: Our understanding of the MACV-SOG missions in Southeast Asia is that they were — even by the standards of Special Forces operations — extremely dangerous, often with very high casualty rates. We also understand that these costs were borne by a very small number of men, and in total secrecy. Is this assessment accurate?

JP: Yes, that is accurate. Although we were called “recon” teams, we conducted a great variety of intelligence and direct-action missions. We planted mines on the enemy’s highway system; ambushed truck convoys; seized enemy prisoners; inserted sensors and beacons; directed air strikes on enemy truck parks, ammo stockpiles and basecamps; planted booby-trapped 7.62x39mm, 12.7mm and 82mm mortar ammo; performed Bomb Damage Assessments on B-52 strikes; wiretapped enemy landline communications; recovered downed pilots; and, searched for American MIA’s (missing in action) and POW’s (prisoners of war).

[Be sure to check out Dangerous Steps: Viet Cong Booby Traps.]

As “recon,” we conducted point and area reconnaissance; surveilled enemy highways; conducted river surveillance on major waterways; hunted for enemy artillery that was firing into South Vietnam; and searched for enemy installations, especially truck parks, supply/ammo dumps, and basecamps.

All these missions were hazardous because we were targeted on locations where the enemy was known — or was suspected — to be in considerable strength. Further, each year that the war continued, the enemy added to his layered and redundant rear area security.

The North Vietnamese increased local security patrols; added night security along roads to detect our surveillance and ambushes; added special platoons to sweep for the same; added armored cars to escort their convoys; added “LZ Watchers” on high hills and tree platforms to watch for our helicopters; added numerous anti-aircraft guns up to 37mm; added light tanks; added human trackers; added tracker dogs; added special “counter-recon” companies and platoons to hunt us down; added Radio Direction Finding equipment to triangulate our locations when we transmitted messages; added artillery to fire upon our suspected locations, and so on. By 1970, the North Vietnamese had 50,000 rear area troops protecting their Laotian highway system.

During the war, 10 of our teams went MIA and another 14 were overrun — but SOG was able to recover their bodies. During 1968, SOG’s losses exceeded 100% because each Green Beret in recon or a reaction force platoon was killed, wounded or missing — as well as some of their replacements.

Virtually every man I knew had a Purple Heart. We used to joke that it did not take much courage to go on one SOG mission — but the second mission demanded courage you didn’t know you had.

By the way, not one of our MIA’s later turned up as a living POW, although post-war, some remains were recovered from downed aircraft sites. However, we knew some men had been taken alive.

In all, we lost approximately 300 Green Berets on these cross-border operations, to include 57 men MIA. These were heavy casualties when you consider that SOG’s three recon companies — Command and Control North (CCN), Command and Control Central (CCC), and Command and Control South (CCS) — were authorized only 60 American Green Berets each (plus indigenous personnel). And we were almost always short of recon personnel.

Combined, CCN, CCC and CCS Green Berets received 10 Medals of Honor, which included four presented posthumously. Many other high awards went unapproved because higher authorities could not be told the classified details of many actions. A couple of years ago we had a Distinguished Service Cross upgraded to the Medal of Honor, 47 years after the action. It took a decade to accomplish this. The recipient, Gary “Mike” Rose, invited a number of us (including me and my wife) to the White House to watch President Trump present the award. That was one fine day.

TAL: We know that narrowing this down to one choice is probably a tall order, but what do you feel was your most memorable mission with SOG? And beyond that, any missions of which you are aware that you may not necessarily have been a part of?

JP: Without question, my most memorable action was Operation Ash Tray Two, the night ambush of a North Vietnamese truck convoy on Laotian Highway 110 and capture of a high-value enemy prisoner. The enemy’s Laotian highway system was vital to their fighting in South Vietnam. Some 10,000 trucks (no exaggeration) carried their supplies from North Vietnam through Laos to South Vietnam. This “Ho Chi Minh Trail” included 2,500 miles of roads constructed and defended by the enemy.

Due to my experience (I’d already been in recon 15 months), I led this mission, which included eight American Green Berets and four indigenous Montagnard tribesmen. The challenge was to halt a convoy’s lead truck, capture the driver and withdraw after taking him prisoner. This driver was especially valuable because he would know where enemy stockpiles and truck parks were located, and what they’d recently been hauling.

We spent two weeks devising and practicing our ambush so we could halt the truck with explosives and seize the driver in less than one minute. That’s exactly what we did on the night of March 29th, 1970, as well as lit the truck afire with explosives. Enemy soldiers fired on us as we withdrew, badly wounding one American with AK fire; I was standing beside him when he was hit, and I later took (minor) frag wounds from an enemy grenade. But we all made it out and marched all night for a helicopter extraction at first light. Thanks to numerous air strikes, our Hueys took no ground fire.

My SOG comrades ran many other dramatic operations. In some way, given the dangers, just about every cross-border op was “memorable.” The enemy hunted us relentlessly and many, many times we had to shoot our way out and took ground fire during extraction.

I think my experiences were typical — in 22 operations, my teams had to shoot our way out 19 times. Many, many times our teams escaped by the skin of their teeth. That’s why, between missions, we practiced live-fire drills practically every day.

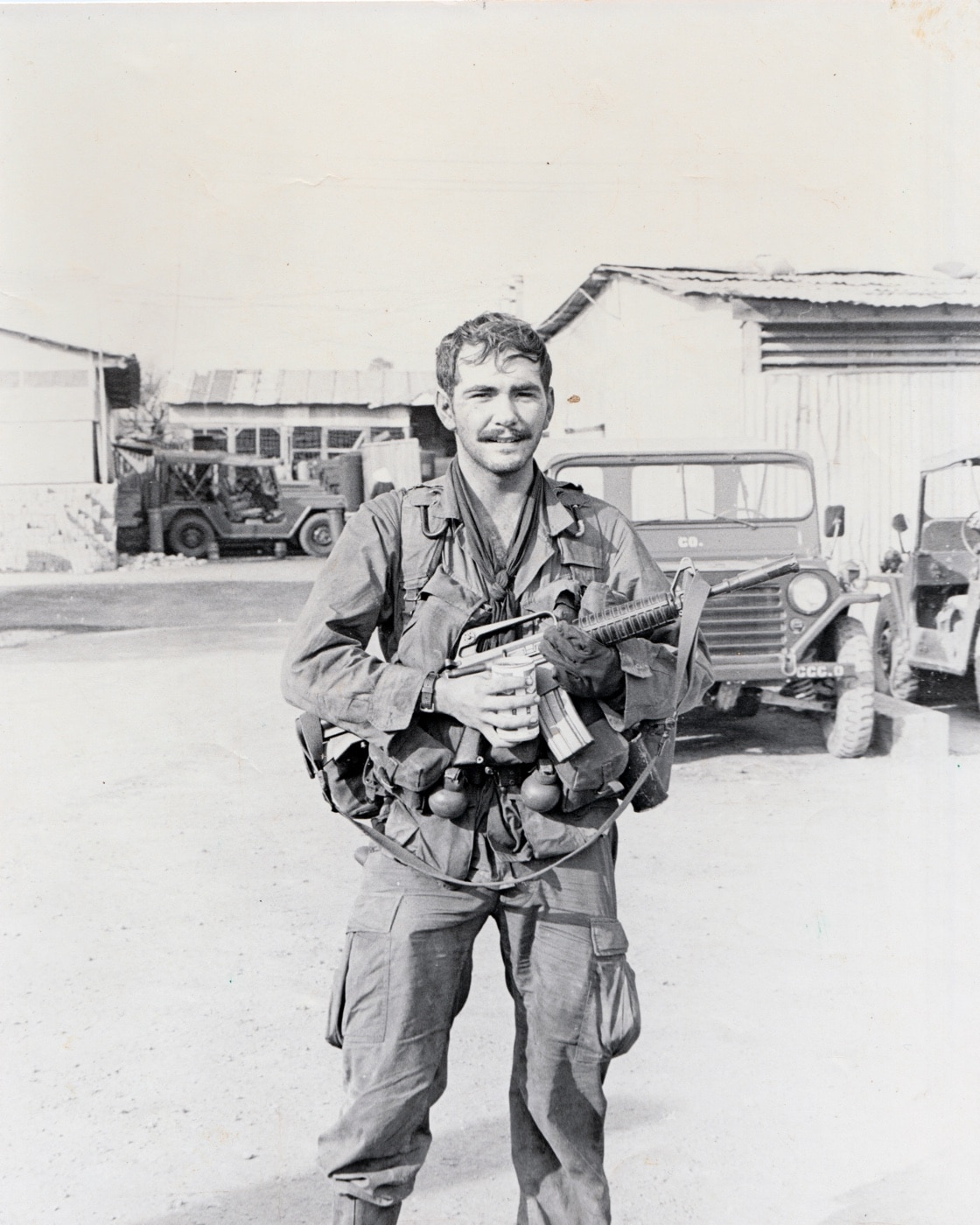

Our shooting skill and tactical knowledge gave us a thin — but decisive — edge over the enemy. And 99% of the time, the enemy we fought outnumbered us, at times 10-to-1 or more. That’s why we packed a lot of ammo — I normally carried 22 magazines for my CAR-15, plus HE, CS and White Phosphorous grenades, which was typical.

TAL: Looking back over your decades of experience, how do you see the role of special forces today versus when you served? Would you change anything about how they do what they do now? Or, would you change anything about how you did things back then?

JP: Occasionally, I am honored with the chance to speak with today’s Green Berets, especially concerning ops in Iraq and Afghanistan. (They refer to us old guys as “Gray Beards.”) Today’s technology is amazing, from satellite phones to thermal scopes and square-rig parachutes.

But, what has impressed me the most is the quality, character and dedication of these men — absolutely the best. Oftentimes they don’t get credit for what they do (sound familiar?). But it’s not about recognition, it’s about their comrades, their missions and the traditions they uphold. And that is just like my old SOG days.

TAL: Can you tell us about your experience with the M14/XM21 family in service (and beyond), specifically the XM21 variant we believe was used in limited numbers by SOG?

JP: In 1967, the M14 was my rifle during Basic Training. Having fired it extensively, I appreciated its accuracy and handling and the performance of the 7.62mm NATO cartridge. During my second SOG tour (’69-’70), the XM21 rifles arrived. Up to that point, our sniper rifle was a Model 700 bolt-action with Redfield 3-9X scope. It was identical to the Marine sniper rifle, but SOG was the only U.S. Army unit in Vietnam armed with it.

Immediately I liked the XM21’s looks and feel, despite it weighing two pounds more than my earlier M14, and four-plus pounds more than my 5.56mm CAR-15. The trigger was still two-stage, but notably improved. However, the stock was configured like the M14’s without a cheekrest, making eye-alignment an issue.

Like the original M14, our XM21’s stocks incorporated a hinged buttplate that had no business on a sniper rifle. Like the BAR automatic rifle, I think this style buttplate was intended for controlling the M14 while firing full-auto prone.

We had only standard, 20-round magazines, which required the shooter to raise his body dangerously above the ground. As well, when shooting prone, the shooter often had to support the rifle on his elbows, a position that’s not especially solid.

As I recall, we were warned not to remove the action from the stock for cleaning, and to avoid letting solvents get below the action because it could soften the glass-bedding material.

Despite its complicated appearance, the scope was simple to operate — after it was zeroed.

Because the unique Leatherwood mount was moveable, in essence you were zeroing both the mount and the scope. This was not a big problem, unless you ran out of elevation or windage while zeroing the scope and had to realign the mount, recenter the scope and start again. Once zeroed, of course, the optics performed well.

TAL: Speaking of the XM21 and the M14, we recently presented you with a “Crazy Horse” M21A5-pattern rifle built off of a Springfield Armory M1A. The work was done by the M14 experts at Smith Enterprise, Inc. Mind letting us know your thoughts on it, compared to the XM21 of the SOG days?

JP: Today’s “Crazy Horse” rifle, based on Springfield Armory’s M1A, may resemble the M14, but that’s only superficial. Internally, the extensive modifications achieved by the pros at Smith Enterprise not only addressed issues with the original XM21 concept, but I believe achieved the highest standard for a target-grade, semi-auto rifle, with the excellent M1A rifle as a solid foundation.

[Read about the Crazy Horse M21A5 rifles developed by Smith Enterprises.]

Fortunately, shooters today are no longer limited to only 20-round mags that make going prone difficult, with 10-rounders and 5-rounders readily available from Springfield Armory. My Crazy Horse is topped by a Leupold Mark 5HD 3.6-18x44mm scope, completing this outstanding long-range shooting system.

TAL: Regarding the topic of precision rifles, from your perspective now, has the discipline of sniping changed from your days with MACV-SOG to today? If so, how and why?

JP: The past half-century has seen an astonishing improvement in sniper training, sniper weapons, optics and gear, and the quality of snipers our schools produce. I attribute this to two factors: First, veteran snipers of past conflicts did not want the lessons learned at great cost to be forgotten. They helped re-establish peacetime sniper training and provided the impetus for technological improvements in weapons and optics.

Second: The need for precision shooting dramatically expanded in the past 25 years — especially in the War on Terror. Civilian leaders and military commanders grew to appreciate the role of sniping. No other weapon in the inventory can provide such precise fire on selective targets, with minimal danger to others.

TAL: In your opinion, what were the most innovative or exotic weapons used by MACV-SOG?

JP: SOG had an incredible array of both American and foreign weapons, plus our own modifications of weapons. The most exotic was the Gyrojet pistol, which fired a 13mm bullet-shaped, miniature rocket. Although fun to shoot, most of us thought it was a solution looking for a problem.

We also had a backpack 500-round drum for the M60 machine gun, so awesome that we called it “The Death Machine.” The downside? It weighed nearly 100 lbs. yet it was sometimes employed. We had a chopped M14 rifle that was very compact which fired duplex 7.62mm ammo — meaning each round contained two bullets. Some teams had sawed-off M79 grenade launcher pistols which were snaplinked on web gear as an auxiliary weapon.

[Catch the service history of the M79 “Thumper” grenade launcher here.]

An especially popular weapon was the chopped Chicom RPD machine gun. It was the same length as a Thompson submachine gun and used a modified drum containing 125 belted rounds. It was so well-balanced you could practically write your name with it.

The most unusual weapon was a 50-lb. bow and arrow carried (and shot) by Green Beret Bob Graham on a mission into Cambodia.

TAL: Beyond your service in the military and your efforts around the world training future generations of special forces and snipers, you are also a renowned writer with numerous published books and articles. Can you tell us how you got into writing, and why?

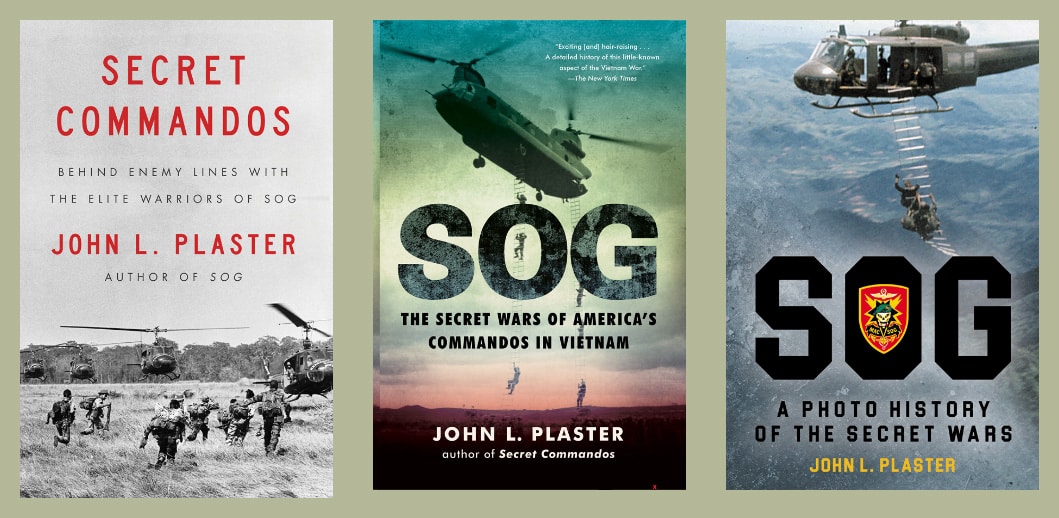

JP: I retired in 1992 and began work on my first book, “The Ultimate Sniper,” which was my best shot at placing everything a sniper needs to know into a single volume. By the time I finished it, SOG’s top secret operations began declassification. I spent the next three years working on my SOG history, “SOG: The Secret Wars of America’s Commandos in Vietnam”, fulfilling a vow I’d made to my lost teammates and other fine men, swearing that who they were and what they did would not be forgotten.

After that, many SOG vets offered me photos, which led to my next book, “SOG: A Photo History of the Secret Wars.” This was followed by, “Secret Commandos”, the story of my three years in SOG and the men with which I had served.

Meanwhile, I’d been asked to write magazine articles for various law enforcement and gun publications, including the NRA’s American Rifleman. Next came, “The History of Sniping and Sharpshooting”, a huge book that covered precision shooting from the 1600s to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, followed by, “Sharpshooting in the Civil War”, and then “Sniping in the Trenches”, the story of sniping in World War I.

Three of my books are still in print and available on my website, www.ultimatesniper.com: “SOG: The Secret Wars of America’s Commandos in Vietnam”, “Secret Commandos”, and “SOG: A Photo History”. My current project is a novel, “The Wolves of Winter”, concerning WWII special ops in Europe.

TAL: What advice would you give to a person now entering the service, with an interest in serving in special forces?

JP: I’ve sometimes been asked, “How should I prepare myself for Special Forces training.” Here’s my best advice.

Firstly, focus on your physical condition. Special Forces training is tough, requiring physical strength, stamina and dexterity. Don’t expect to acquire this during training — you need it on Day One. This is probably the issue that eliminates most Special Forces trainees. Build yourself up as if preparing for an athletic event, with Special Forces training being your Olympics.

Regularly run five miles, pump iron, do calisthenics — sit-ups, push-ups, pull-ups, you know the drill. Long hikes are good, too. In training, the weak-at-heart types get worn out and washed out. However, this often is as much mindset as it is physical condition.

Your mindset is just as important. At least half the men I saw fall out were not physically exhausted — their minds told them they’d had enough. Quitting is easy for some because they’ve never faced anything really demanding in their lives. Mentally toughen yourself, develop self-discipline through occasional denial of creature comforts.

Run an extra 100 yards when your body is telling you you’ve had enough. Personally, at the toughest times I’d tell myself, “Never quit!” or “I’d rather die than quit!” Sadly, I sometimes saw men quit who, only a half-hour later, realized they hadn’t been really exhausted.

You have to be able to swim. At some point you’ll take a swim test, and this is a “go, no-go” issue that relates more to water survival than long-distance swimming.

And lastly, if you can, talk to a Special Forces veteran. The Special Forces Association has chapters in more than 25 locations across the country, and many hold monthly or quarterly meetings. To find the nearest chapter, do a Google search with keywords, “Special Forces Association” plus your city or state. Most former Green Berets are glad to share their experiences with men aspiring to earn their own green beret.

At my class graduation — just before first donning our berets — a seasoned Special Forces sergeant major shared an important perspective. “The green beret is a hat. It’s hot in the summer and cold in the winter, and doesn’t have a bill to keep the sun out of your eyes. You don’t want to be a Green Beret, you want to be a Special Forces soldier. And that means a lot more than any hat you may ever wear.”

TAL: Thank you so much for taking the time to do this interview with us, and for giving us an insight into your fascinating story. We truly appreciate it.

JP: It was my pleasure.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

353

353