The BAR in Korea

December 22nd, 2020

7 minute read

The BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) was designed as an automatic rifle, chambered to fire the full-sized .30-06 round. In the World War I era, the term “machine rifle” was also used. The most important factor to bear in mind is that the BAR is a rifle. Even though it was only used in the closing days of the Great War, the BAR made a huge impression, on both American Doughboys and throughout the armies of Europe.

The interwar period saw a great deal of effort invested by many nations in creating “light machine guns”. Germany led the way in the development of the “general purpose machine gun”. Whether “light” or “general purpose”, the most effective of these designs featured a quick-change barrel.

Automatic rifles normally do not have an easily removable barrel, and the BAR was no exception. When the light machine gun concept was in fashion, U.S. Ordnance added a bipod, carrying handle, shoulder support and flash hider to the BAR. But dressing the big Browning rifle up as an LMG did little to make it more effective, simply adding weight. Even so, the BAR increased its legend throughout World War II. Its battlefield performance more than proved the soundness of the automatic rifle concept.

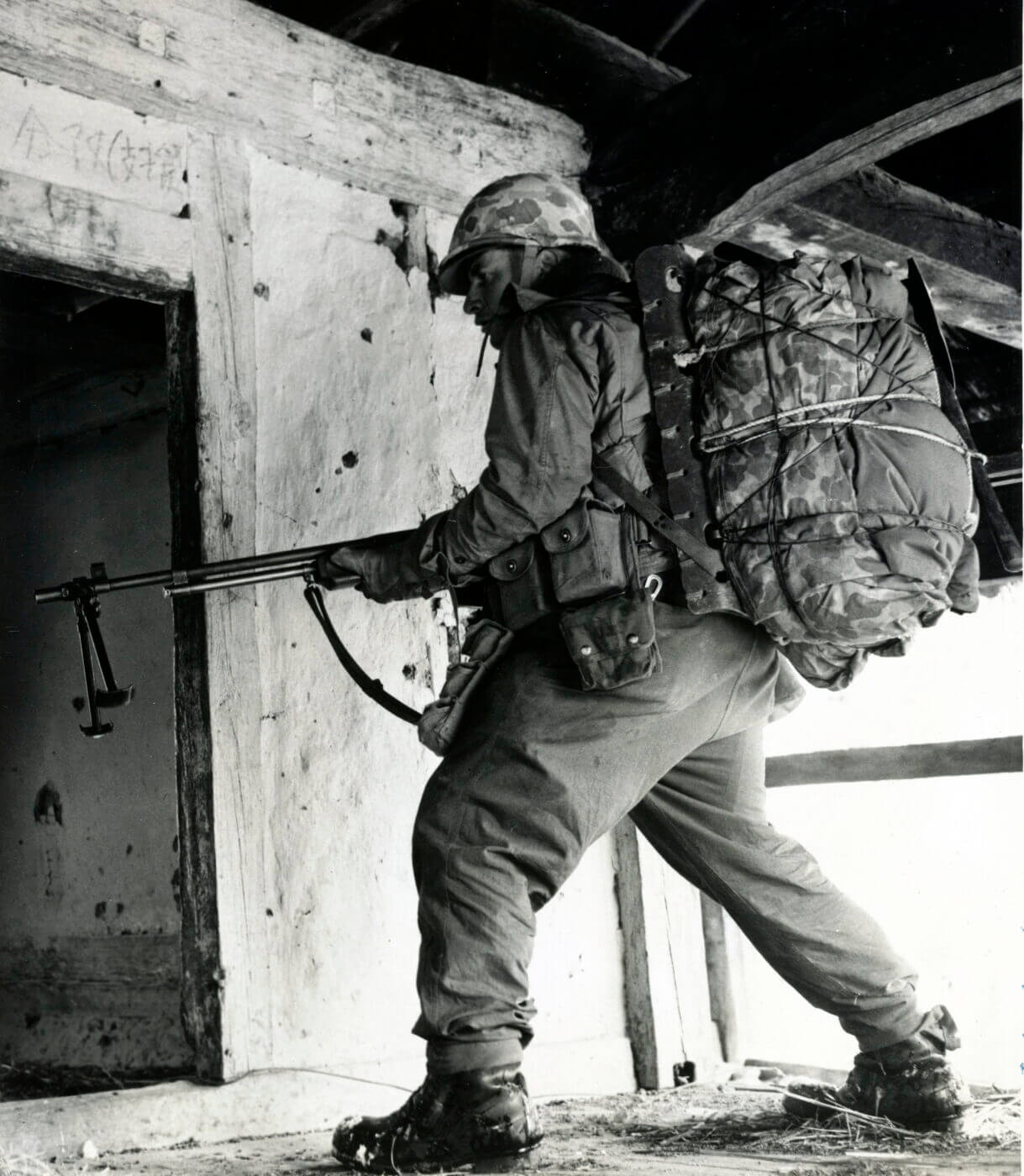

By the time the Korean War began in 1950, many of the hard-learned lessons about how to best use the BAR had been forgotten or ignored. Most of the BARs issued to troops bound for Korea were fitted with the same add-ons that had been taken off and thrown away in the previous conflict. By the end of the Korean War, most BAR gunners had again stripped down their weapons to their original 1918 configuration.

A Landmark Report

In his highly detailed report, “Commentary on Infantry Operations and Weapons Usage in Korea, Winter of 1950-51”, Brigadier General S. L. A. Marshall describes the BAR as “The Mainstay”, and elaborates on the effective use of John Browning’s big automatic rifle in the rugged Korean terrain:

“Under the conditions of the average infantry fight in Korea, the BAR, even more than the machine gun, provides the fire base around which the action of other infantry weapons builds up and the force expresses itself unitedly. the men also make this estimate of its effectiveness; they state frankly that it is the mainspring of their action, and that wherever the BAR moves and fires, it gives fresh impulse to the rifle line.

“Appreciation of the BAR within Eighth Army therefore reaffirms experience with the same weapon in World War II operations both in the Pacific and in Europe…It is still considered “indispensable” and troops shudder at any suggestion that it might ultimately be replaced by some other weapon. They cannot imagine having to get along without it.

“The BAR, which is a lesser target and usually has as its operator an individual who combines boldness with a requisite stealth, is therefore the main counteragent. BAR fire is also the chief depressant of sniper fire delivered from ranges which are too close in for the mortars and too far out for the grenade. One man with a BAR, if he is the right man, will have a stronger neutralizing effect upon a local sniper-infested area than the random fire of five or six riflemen. Almost invariably, BAR men are exemplary in their conservation of ammunition. They do not have nervous fingers; they sustain fire only when the situation truly demands it. Why this is so is something of a mystery; it is recorded here as fact because the BAR record in Korea is one of consistently strong performance by the operators.

“If the machine gun, stopping the enemy frontally, is threatened by flankers circling toward it over dead ground, BAR fire is used to cover the corners and save the gun. During the mop-up, it is the main weapon for neutralizing foxholes.”

Issues with Reconditioning

The onset of the Korean conflict found America rather unprepared. Many of the infantry weapons first issued to units in Korea during 1950 came from stocks of U.S. World War II weapons stored in Japan. Many of these arms and some of the ammunition had been improperly stored, and there were, at first, far too many firearms that failed or would barely function at all. General Marshall describes the hearty and reliable BAR:

“Concerning the new BAR, fresh from the factory, there is no problem. Practically without exception, this weapon has met with full success every test which the inclement weather of Korea and the dust and grime of the countryside have imposed upon it.

“Much of the trouble seemed to be centered in a weakness in the recoil spring, though because of complications due to seeming frost-lock it was not always possible to determine the seat of the difficulty. The check-up revealed that almost without exception, the BARs which had gone out of action were old weapons, reconditioned by Ordnance in Japan. The old springs, it was reported, had been cleaned but not replaced. Also, according to staff information supplied from Tokyo, the inspection system … during the initial phase of the weapons-reconditioning program had been technically inadequate and generally weak, with the probable consequence that some of the rebuilt weapons had not been adequately tested … invariably where the weapon had failed, it was a reconditioned BAR.”

In the Okinawa campaign of the spring of 1945, USMC units had significantly increased the number of BARs among Marine infantry while reducing the number of M1 Carbines. In a decision driven by combat experience, the Marines chose automatic firepower, along with the range, accuracy and penetrative ability of the .30-06 round. World War II was over within a few months, and much of this thinking was either shelved, ignored or forgotten. General Marshall remarks on how the power of the BAR was “rediscovered” in Korea, and the concept of doubling the amount of these weapons was renewed.

“In the view of the great majority of infantry troops and commanders in Korea, the fighting strength of the infantry company would be greatly increased by doubling the number of BARs, while reducing the number of M1 carriers proportionately. This could be done without adding an upsetting burden to the company load. The final argument for the change is that it would make more perfect the balancing of offensive-defensive strength within the infantry company.”

The M14 as the Squad Automatic

As the M14 became America’s battle rifle, additional work was done to allow the M14 to replace the BAR in the role of squad automatic. Most battle rifles of the era had a squad automatic version, including the Soviet AK-47, the G3, the BM59 and the FN FAL. All of these had their good points, but none were a fully satisfying answer to the squad automatic question.

The M14E2 featured an in-line stock and a large pistol grip intended to help control the weapon during full-auto fire. A plastic upper to the forend was added to save weight, but this weight saving was undone by the addition of an M2 bipod, muzzle brake/compensator, and a folding metal vertical foregrip.

The weapon was, at best, a compromise, subject to the same problems of others in its class, including rapid overheating, and the inability of magazine-fed weapons to sustain automatic fire. Even so, the M14E2 was approved for production and issued beginning in 1963. By 1966 it was redesignated the M14A1 and faded from service as the M14 was replaced by the M16.

The Legend Lives On

The Browning Automatic Rifle remained in service, appearing in some numbers in the Vietnam War during the 1960s. Clearly, its influence was felt across multiple generations and designs of battle rifles, light machine guns, and squad automatic weapons. All these years later, the BAR is still heavy, intimidatingly so for some. It is also still accurate and hard-hitting. What’s more, it is still a legend.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

265

265