The Final Shot Fired at the Berlin Wall

February 10th, 2022

6 minute read

Berlin, April 8, 1989.

Saturday mornings were always busy at the checkpoint at Chausseestraße, and April 8th was no exception. Queues had already formed on both sides when a taxi dropped off Michael Baumann and Bert Greiser shortly after 9:00 a.m.

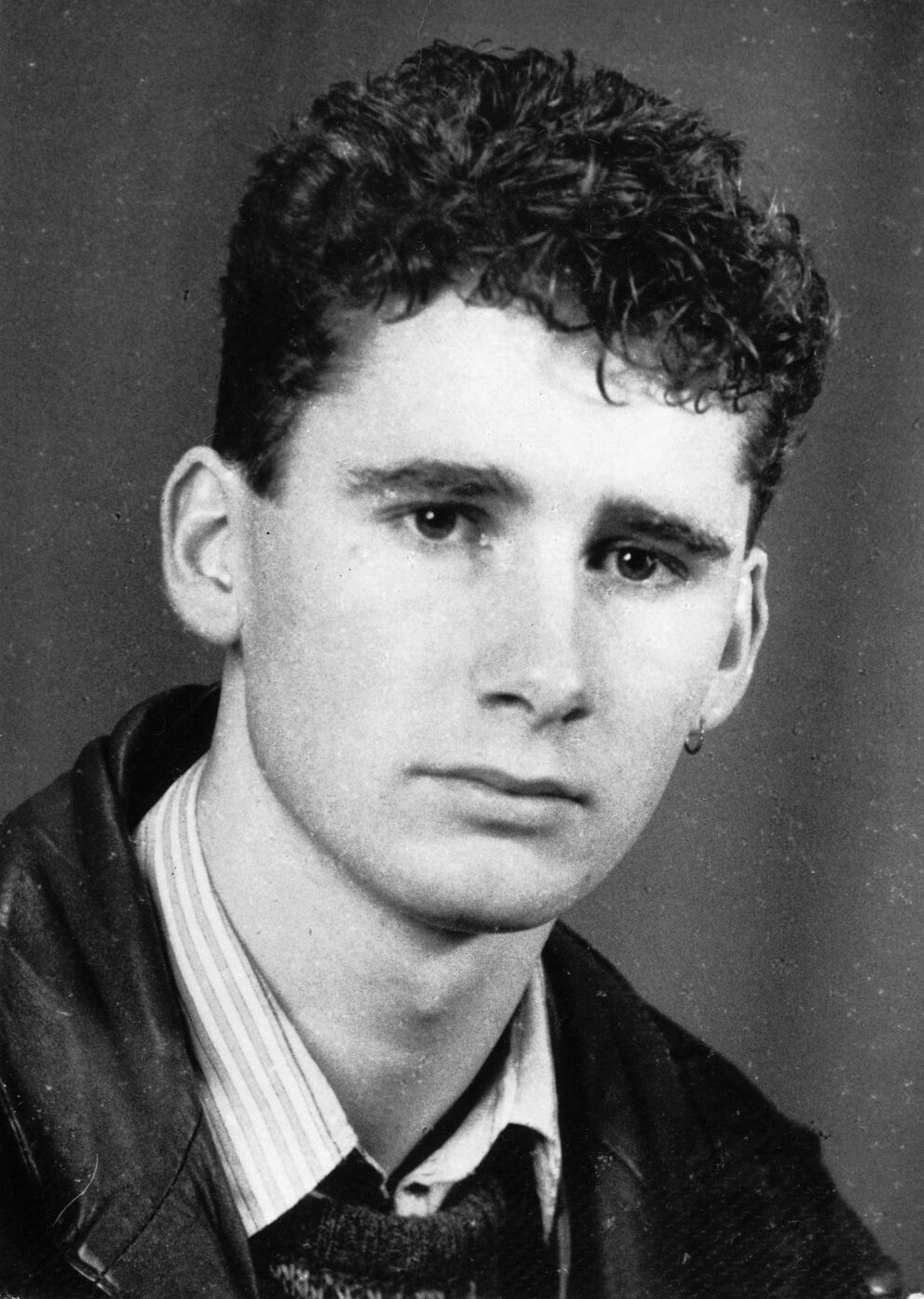

Wearing sneakers and sweatpants, the two East Berliners took their place in the queue and watched and waited. For 10,100 days the city had been divided by a wall that physically partitioned it just as the country itself had been as a result of the confrontational politics of the Cold War. Baumann and Greiser were both born in the east in 1962, so they had known nothing but the wall and the oppressive Deutsche Demokratische Republik (German Democratic Republic or “DDR”) that built it.

Like so many other young East Berliners before them, Michael and Bert imagined escaping to the socially liberal and more open West, but that was a dangerous idea during the era of the Antifaschistischer Schutzwall (or “Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart”) as it was euphemistically known in the East.

The wall and the strip of ground it was built on were protected by barbed wire, guard towers, guard dogs, anti-personnel mines, machine guns, and the DDR’s controversial Grenztruppen (“border troops”) who patrolled it around the clock. They were there to prevent East Germans from escaping into West Berlin, and they had a deadly reputation because of the Schießbefehl (“order to fire”), a standing order to shoot anyone attempting to defect by crossing the wall — a crime known as Republikflucht.

By 1989 Grenztruppen personnel had killed 140 East Berliners at the wall, with the most recent case happening just two months earlier when 20-year-old Chris Gueffroy was shot attempting Republikflucht during the night of February 5th.

The death of Chris Gueffroy brought down international condemnation on the DDR government and its embattled head of state, Erich Honecker. To make matters even tenser, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev had embraced a policy of détente with the West, and shooting unarmed defectors was just not in harmony with that.

In response, Honecker quietly revoked the Schießbefehl on April 3rd with the words, “It is better to let a person run away than to use a firearm in the current political situation.” Although Baumann and Greiser did not know for sure that this had happened, they suspected it. Change was in the air in East Berlin, and with each passing month, it was becoming clearer that the old antagonisms that had given birth to the wall 27 years earlier were beginning to slip away.

So, the two men came up with a plan: they would proceed to the checkpoint at Chausseestraße where Berliners on foot and in automobiles were allowed to cross between Berlin-Wedding (in the West) and Berlin-Mitte (in the East). Even though they did not have credentials to do so, they would line up in the handling queue to cross into the West with the credentialed pedestrians, but then when the Grenztruppen raised the vehicular barrier to allow cars to drive into the checkpoint, the two men would run through it as fast as their feet would carry them.

They only had to cover 500 feet to freedom, but they had to cover it quickly, so the two trained for months by sprinting and jumping hurdles at nearby Stadion der Weltjugend (“Stadium of World Youth”). Earlier that morning, they warmed up by running a few laps there and then climbed into the taxi that dropped them off near the checkpoint.

In the interest of documenting what was about to happen, Greiser had informed a friend in West Berlin when and where he and Baumann would make their escape from the DDR. That friend had taken up a position on the West side of the checkpoint in an observation tower so as to photograph what would hopefully be a successful Republikflucht.

The Day

At 9:30, one of the Grenztruppen raised the barrier to allow an automobile to enter the checkpoint, and that is when Baumann gave Greiser the signal. They burst through the open gate and then hurdled a waist-high barrier beyond it like a couple of gazelles.

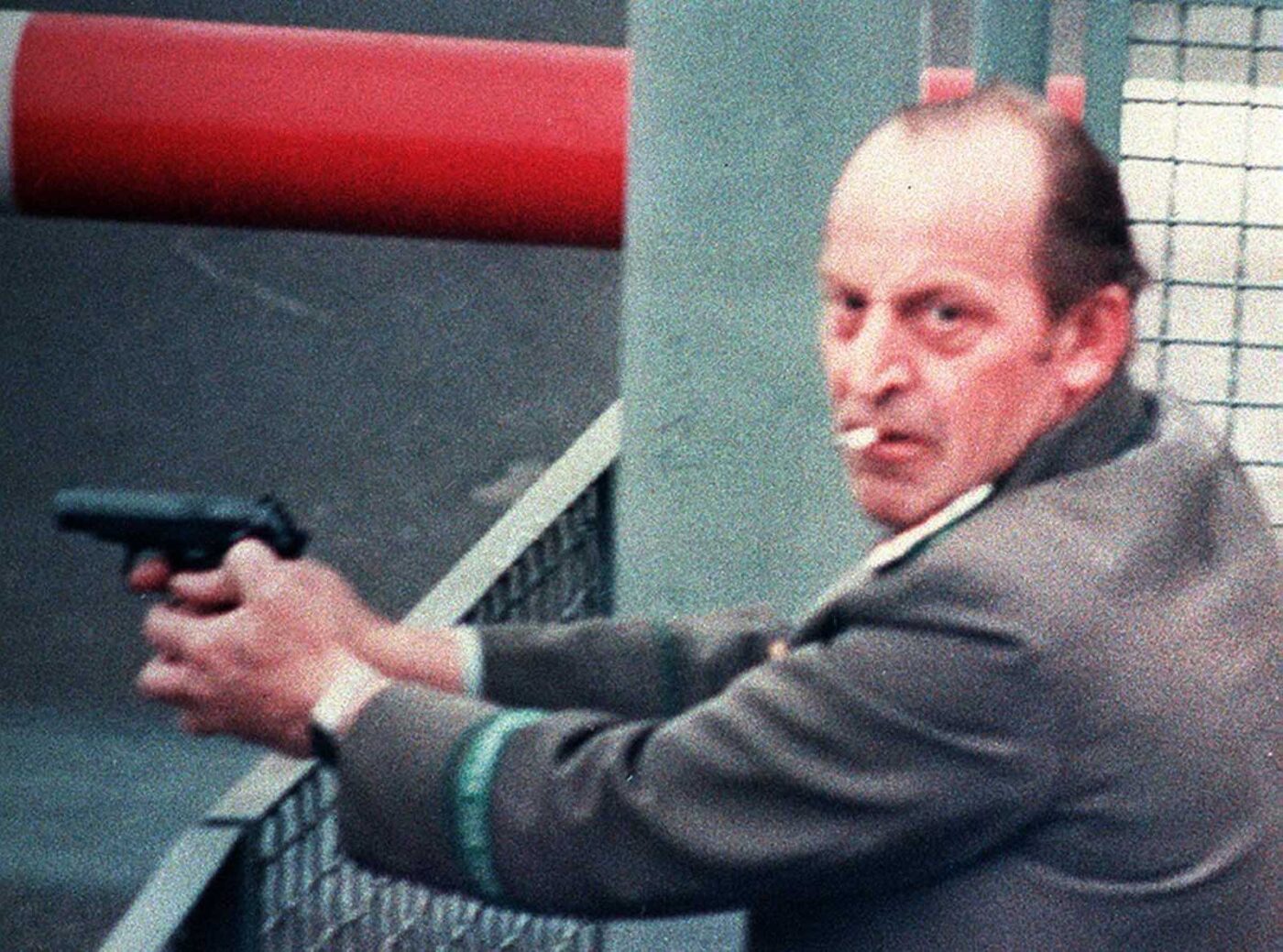

Before the Grenztruppen could react, the defectors were halfway through, but they had been noticed by a Passkontrolleinheiten (“Passport Control” or PKE) officer in the last guardhouse. With a lit cigarette in his mouth, the officer stumbled outside, shouted for the men to stop and drew his sidearm.

Baumann and Greiser were only 20 feet from West Berlin when a single shot rang out. They wanted freedom, not death, so they had agreed ahead of time to surrender immediately if shots were fired. Since that threshold had been crossed, both men stopped and put their hands up.

East German border guards armed with MPi-KMS-72 assault rifles hastily swarmed the would-be defectors and took them into custody. Although the entire incident was photographed as planned, Baumann and Greiser’s attempt to reach the West had been foiled by a single gunshot, and the man who fired that shot was caught on film just moments after he pulled the trigger.

The image shows him scowling toward the camera and because he was still smoking at the time, the press quickly gave him the nickname “Kippe-Schütze” — the “cigarette butt shooter.”

The “Kippe-Schütze” was technically not a part of the Grenztruppen, he was a part of the DDR’s Ministry for State Security, or “Stasi” as it was infamously known. When Erich Honecker revoked the Schießbefehl the week before, the news had only reached the Grenztruppen which is why they held their fire as Baumann and Greiser bolted through the Chausseestraße checkpoint that morning.

Since the Stasi did not get the memo, the PKE remained unaware of the change in policy, and that is why the “Kippe-Schütze” did not hesitate to let off a round when none of the other guards would. Fortunately, his bullet did not strike either Baumann or Greiser — but harmlessly zipped off into the no-man’s-land separating East Berlin from West Berlin.

As it turns out, his shot from an East German Makarov was the final shot fired at the Berlin Wall. Throughout 27 years of tense Cold War brinksmanship, firearms had been discharged hundreds of times, but the “Kippe-Schütze” squeezed the trigger on the final round.

Conclusion

While that shot may have prevented Michael Baumann and Bert Greiser from defecting on April 8, 1989, it could not stop what was coming. Just 215 days later — on November 9, 1989 — the wall came down and, after 27 years of being two cities, Berlin became one city again.

Baumann and Greiser could not join the crowds of celebrating Berliners though because they were both serving prison sentences at the time, but they did get to watch the celebrations on television.

Just a few days later they were released, and the following year the era of the DDR came to an end when Germany reunified. Although the DDR is now long gone, Baumann and Greiser are both still alive and well and they are both still living in Berlin.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

407

407