The First Russian-Ukrainian War … of 1919

April 7th, 2022

8 minute read

The spring of 2022 is not the first time that Russian forces have invaded Ukraine. The tumultuous days in Eastern Europe that followed World War I showed that the November Armistice between Imperial Germany and the Entente/Allied forces only applied to Western Europe. The war would continue in the East, no longer under the umbrella description of “The Great War,” but rather minimized as a series of civil wars or territorial disputes.

The brutal reality of the 1919-1921 era, seldom mentioned in Western nations, would see the sudden emergence of the Soviet Union and a wide range of border-clash bloodlettings. All the old ethnic hatreds, distrust, and reprisal upon reprisal would be on full display. Modern notions of nationalism, communism, socialism and capitalism were stirred into the angry pot along with all the traditional motivations for war. It was a time for killing.

Setting the Stage

In this struggle for democracy, which the Ukrainian people have been carrying on for 400 years and in which they have never lost their hope and determination, they have a right to count on the assistance of other democratic nations and to expect the people of America and England in particular, not to abandon them. After this long struggle of 400 years’ duration, a time has come when these two powerful democracies of western civilization can and should lend Ukraine a helping hand.

Ukraine on the road to Freedom. A selection of articles, reprints, and communications concerning the Ukrainian people in Europe. 1919

As WWI still raged, German and Austrian troops drove the early communist Bolshevik forces out of Ukraine, capturing Kiev on March 1, 1918. With their backs against the wall, Lenin and his Bolshevik government signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918, and the traditionally Russian-dominated “borderland” territories of Ukraine and Belarus were turned over to the Central Powers.

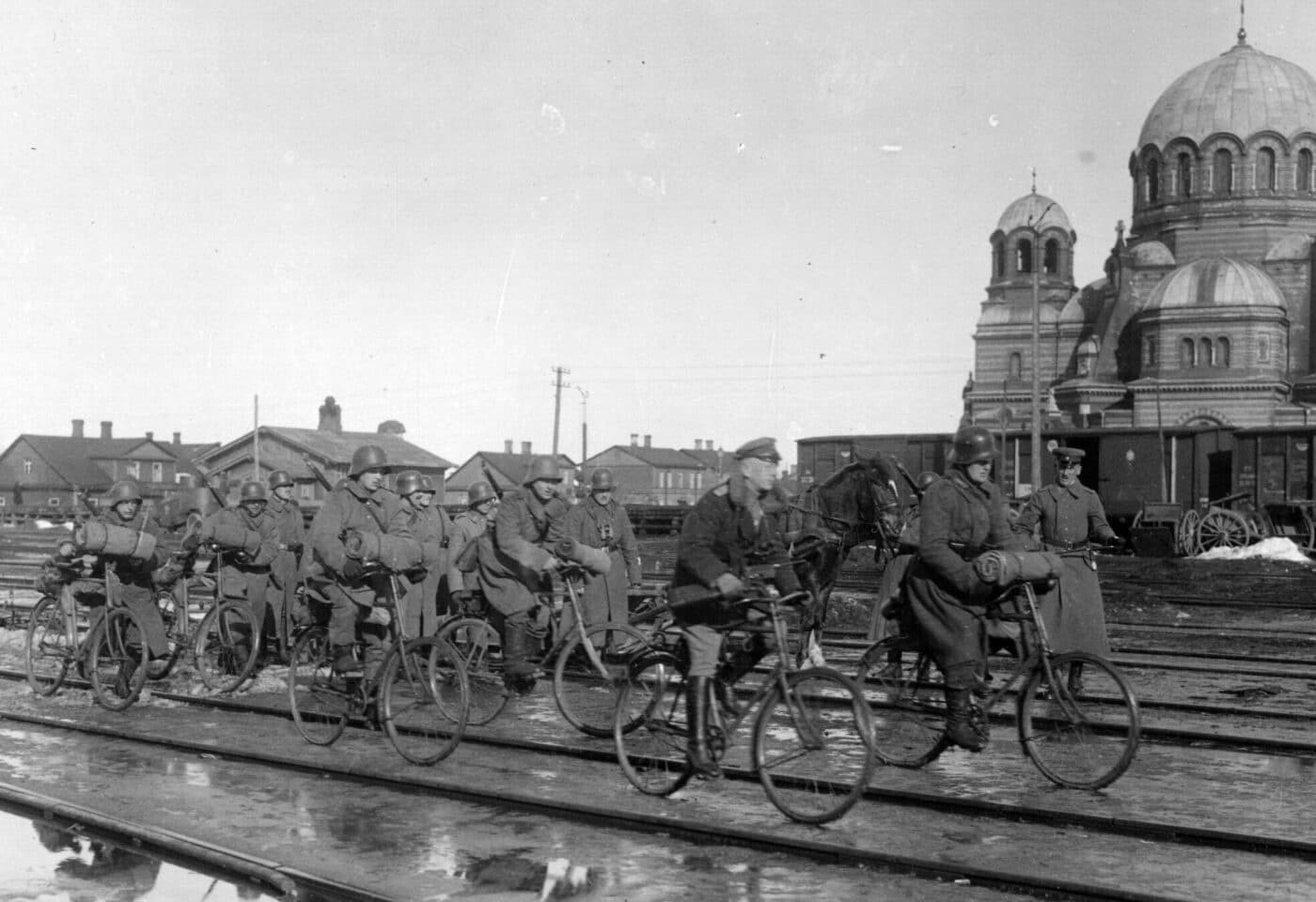

German/Austrian forces quickly occupied the totality of Ukraine, and with the help of a German-inspired coup, General Pavel Skoropadsky became the “Hetman” (an ancient title for the leader of the Ukrainian Cossacks) in control of Ukrainian territories. When the Central Powers were defeated in November 1918, German troops left Ukraine, and the nation was swept up in the mayhem of the Russian Civil War.

The German withdrawal left a power vacuum, and the Bolsheviks moved quickly to secure the supremely valuable territory in Ukraine, known as Europe’s breadbasket. The military situation was, by any standard, extremely confusing. Ukrainian national forces (the Ukrainian People’s Army, or UHA) and militias battled the communist Red Army, the anti-communist Russian White Army, the fledgling Polish Army in the west, sometimes the Romanians, and quite often the Ukrainians each other. Kiev changed hands nearly a dozen times until the Bolsheviks took control on December 16, 1919.

Building an Army

In the immediate aftermath of World War I, troops that had served in the imperial armies were readily available. So too were many weapons, but they were often a jumbled mass of manufacturers and calibers. With many of the men war weary from their time in the Great War, and the weapons a logistical nightmare, the Ukrainians set out to assemble a national army.

When the Austrians left western Ukraine, they left behind large stocks of weapons. Consequently, the UHA initially relied on Austrian small arms. The Ukrainian infantrymen carried the Mannlicher M1895 rifle, while officers were armed with the Roth-Steyr Model 1907 semi-auto pistol (8mm Roth-Steyr). The primary machine gun inherited from the Austrians was the water-cooled Schwarzlose M.7.

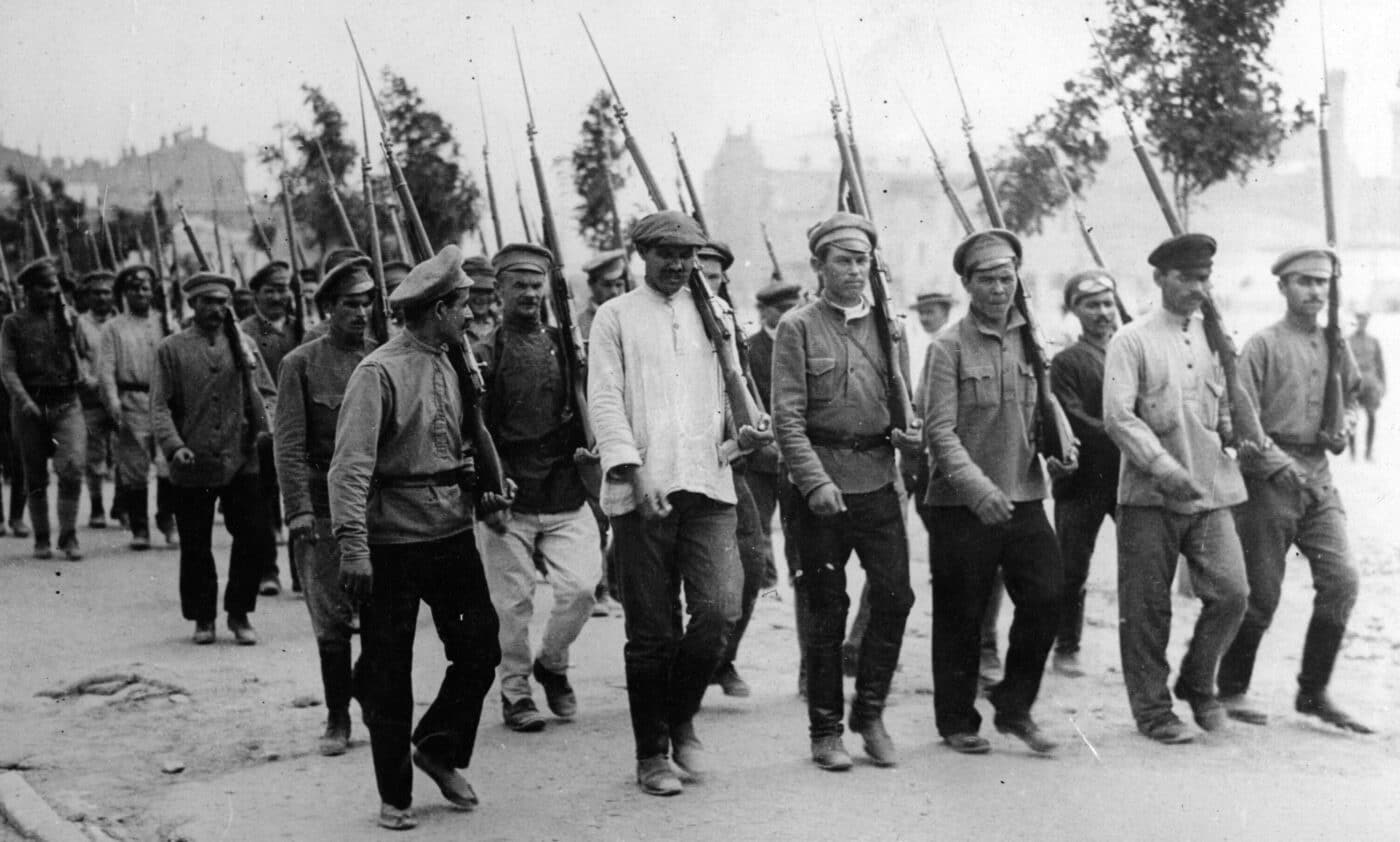

In early 1919, as the stocks of Austrian ammunition ran out, the UHA abandoned their Austrian weapons and rearmed with readily available Russian small arms. For most Ukrainian units, the basic rifle became the Mosin-Nagant M1891 (7.62x54mmR). To the north, the M1891 had been the primary rifle of the Czar’s army, and it remained so with the Bolsheviks in charge.

To the west, the Poles preferred Mauser and Mannlicher rifles, but many Polish troops carried the Russian Mosin-Nagant as well. Availability quickly became the best capability among the combatants in Eastern Europe, and the Ukrainians suffered a shortage of small arms throughout the fighting. The number of available rifles, rather than the number of men, determined the size of their army.

Machine guns were always in short supply, and over the course of the conflict, the Russian Maxim PM1910 gun (7.62x54mmR) became the most common of the heavy MGs. The Maxim was steady and reliable with a cyclic rate of 600 rpm. Fed by 250-round belts, the Maxim was normally found on the wheeled Sokolov mount with the gunner protected by a light armored shield — the gun and mount weighing in at a hefty 138 lbs. The American Colt-Browning M1895 gun was also used in some numbers; the 7.62 variant of the “potato digger” had been used by Russian forces throughout World War I. German MG08s (7.92x57mm) and Austrian Schwarzlose M.7s (multiple calibers) were also in Ukrainian service as ammunition supplies allowed.

Meanwhile, the fledgling Ukrainian nation began to acquire munitions as best they could, many coming from Czechoslovakia in exchange for crude oil from the Boryslav oil fields. Supplies began to trickle in during early 1919, as trucks, artillery, and a few military aircraft arrived. A few armored trains were built, and these rolling artillery platforms were an important element in the Russian Civil War. Training and coordination were still scant though, particularly for engineers, communications troops, and mechanics.

I try to put myself in the shoes of a Ukrainian or Bolshevik or Polish infantryman during the fighting in that era. While I am a good shot, I am a horrible gunsmith. A rifle that does not shoot is little more than a club, and none of the combatant forces in Ukraine had the time or logistical organization to train men in weapons repair. Consequently, it was a lucky brigade to have a strong cadre of armorers — troops with a higher state of combat readiness performed better in the field and tended to maintain their morale and effectiveness.

Morale was a major factor for most of the combatant forces. For the UHA, when it was advancing, their ranks remained full. After a few setbacks, or when the pay and the supplies were running short, the “summertime soldiers” faded away from camp. Across the lines, the Bolshevik commissars were harsh, often cruel, in their discipline. The rank and file of the Red Army was often more afraid of their own officers than they were of their enemies.

Despite the hardships, confusion, logistical problems and overall lack of weapons, the Ukrainians introduced certain battlefield innovations that made the most of what they had. The open plains of the Ukrainian landscape provided the impetus for a new style of warfare that leveraged some antique technology. The UHA’s Colonel Mishkovsky devised tactics for mobile infantry, with the men carried into battle aboard horse-drawn carts and wagons. Maxim machine guns were mounted on small, quick carriages, normally drawn by a pair of horses — the mobile firepower combination was dubbed “Tachanka”. These carriages could still be found in Soviet service during World War II.

As the fighting progressed, horse-drawn infantry, machine gun, and artillery units were in use with the UHA. Ground support aircraft became part of the mix as well, sometimes featuring nothing more than the observer throwing grenades from the rear cockpit.

Bolshevik Invasion of 1919

The Soviet invasion of Ukraine began on January 7, 1919, as Bolshevik troops poured across the border from the north. Joseph Stalin was one of the senior communist officers. Soviet forces received aid from communist groups within Ukraine, and Kiev fell to the Bolsheviks on February 5, 1919. The Soviets rolled on and most of the Crimea was in communist hands when Sevastopol fell on April 29th.

But when it began to look like a rout, the ugliness of the communists and their Chekist assassination squads began to make themselves known. As the Bolsheviks outstretched their resources, the Ukrainian people fought back behind the lines while the Ukrainian and White armies advanced against the communist front. By mid-June, the Reds were pushed out of the Crimea. In July, the Ukrainians made peace with Poland in the west. By August, Kiev had been recaptured and most of Ukraine had been liberated.

It was almost a happy ending, until it wasn’t. In December 1919, the Bolsheviks were back in control in Kiev. A Ukrainian offensive in May 1920 almost retook the city, but Marshal Semyon Budyonny’s cavalry pushed them back, and then continued to Poland, nearly capturing Warsaw before the Poles drove the Bolshevik horsemen back.

When Poland signed a peace treaty with the Soviet Union in October 1920, the Red Army was able to turn its full attention to conquering Ukraine. The end the war officially came on November 17, 1921, but that was not to be the end of the killing. Bolshevik reprisals and murders by the Cheka continued for several years. The communist nightmare engulfed Ukraine and lasted until August 1991. Russia would invade Ukraine again in March 2014, when Putin’s forces annexed the Crimea and supported Russian “separatists” in their attacks in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

On February 24, 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine once again. This time the entire world is watching and learning what Ukrainians have known for more than a century. Let’s hope history is more kind to the Ukrainian people this time around.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

324

324