The No. 4 MK I (T) Sniper: A Solid Foundation

December 5th, 2020

6 minute read

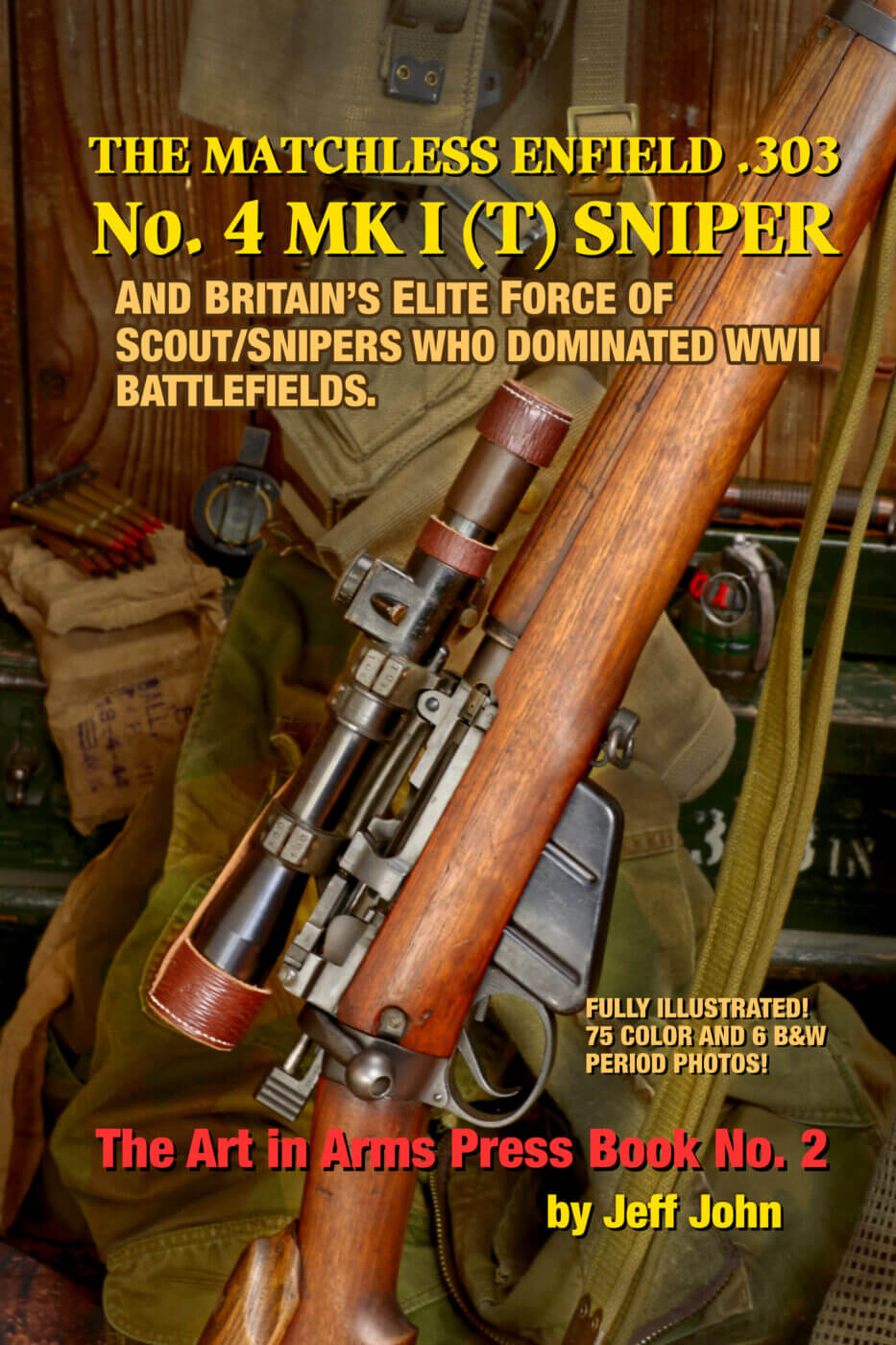

Editor’s Note: Following is an excerpt from The Matchless Enfield .303 No. 4 MK I (T) Sniper by Jeff John, and is part one of a three-part series. If you would like to pick up a copy for yourself, it is available at Amazon.com. To learn more, visit Jeff-John.com.

Read part two of this series at “The No. 4 MK I (T) Sniper: Battle-Ready Accuracy” and part three at “The No. 4 MK I (T) Sniper: At the Range.”

Homely and rough as a cob, the British Enfield No. 4 endeared itself to no one, especially those seasoned soldiers used to the old smooth-working No. 1 Mk III with its distinguished, all-business profile. But it had all the attributes necessary for a fine battle rifle and an equally fine sniper. Except for the looks, the rest was fixable. The action smoothed up from use (although the sniper was slicked up during conversion).

Source Materials

The Lee system was the oldest rifle design still serving and harkened back to the 1870s. Two important concepts were its rear-locking action and detachable box magazine. In an odd twist, the detachable magazine was never developed into an interchangeable detachable magazine, the logical progression of the system.

As originally designed, the American Lee featured a conventional one-piece stock. While the two-piece stock is more economical and proved very practical, I believe its primary advantage is to prevent the stock from cracking just at the rear of the action at the wrist. It’s something I’ve found many original American-made Remington Lee military and sporting rifles are prone to do.

Paul Mauser solved the problem by including a recoil lug to the receiver fitting into a mortise in the stock just under the chamber, a solution almost every bolt-action rifle uses to this day. Without the lug to arrest recoil, the tang of the action acts as a splitting maul to the wrist of the stock over time.

The British designers took another path and split the stock in half, adding the solid steel butt socket at the point original Lee rifles were prone to crack. The method of using a through-bolt to attach the stock was long known to enhance strength and accuracy in single-shot target rifles, and was used in the earlier Martini-Henry.

The Details

The biggest criticism cited about the Lee involved the locking lugs at the rear of the bolt, since such a feature isn’t normally considered suitable for high-pressure cartridges. But the Enfield, never envisioned for high-pressure cartridges, works just fine with the .303 British, and made the jump to 7.62 NATO. Sporting versions of the Lee-Enfield were made in cartridges in the same modest pressure window that were still powerful enough for many big game species. Such hand wringing is misplaced. The system works perfectly well, even if it isn’t adaptable to Herculean tasks.

The Enfield action is “cock on closing,” too, meaning the striker isn’t set until the bolt is pushed home against the striker spring and closed. “Cock on opening” exemplified by the Mauser system compresses the striker spring as the bolt is lifted, requiring more initial effort, yet remains today’s preferred method of operation. Both systems have their champions, and it remains a good way to start an argument around a campfire. For me, the Enfield wins because it’s quiet and smooth.

The Lee-Enfield action can be cycled more quietly than the Springfield, Mauser or Mosin-Nagant. Bolt lift is light, too, since it isn’t camming anything into battery, and can be done with one finger. Cocking effort on closing requires little extra pressure and is easy, even though it causes many Mauser aficionados to sniff disapprovingly. The sight picture is little disturbed cycling a Lee-Enfield, unless you bump your nose with the bolt.

The safety is conveniently out of the way of the optic, completely quiet and easy to operate. Mounted on the left rear of the action, the safety engages by rotating back to lock the bolt closed and disconnect the trigger. The thumb of your shooting hand pushes it forward to disengage without disturbing your grip, unlike many other rifles requiring you to remove your shooting hand from the pistol grip to operate.

As an additional safety, the cocking piece can be pulled back to a safety notch from which the rifle can’t be fired, and locks the bolt closed. Pulling the cocking piece to half cock, then to full cock, causes two very loud clicks compared to simply working the bolt to cock the rifle. On half cock, the cocking piece must be pulled to full cock before the bolt can be opened. The safety can be applied with the striker cocked or uncocked, but not when it is in the half-cock position. It is one of the few questionable features, and one almost eliminated on the No. 4, but in the end it was kept.

The No. 4’s trigger is an all-military two-stage type, but the workmen at Holland & Holland fine tuned them for a decent letoff. The initial take up of the test rifle is right at 4 pounds, and the final pull a crisp 2 pounds. The cumulative total of 6 pounds is at the upper level permissible to H&H.

Many consider the fact the Enfield’s trigger is pinned to its triggerguard instead of being hung from the receiver to be another downside. There is wood between the two, and if the wood swelled and shrank with weather, the trigger pull would change. This only caused a problem on infantry models when poorly seasoned wood was used, something not unusual during the exigencies of war. During postwar overhaul, many triggers were pinned to the receiver and those rifles named the No. 4 Mk 1/2.

Because sniper rifles were manufactured to higher standards from the get-go and saw better care, it is rare to find one so converted. Again, the trigger pinning was never a problem when properly seasoned wood was used. Added insurance was the fitting of a steel pillar between the receiver and the triggerguard for its screw. Done properly, there is steel supporting both contacts between the triggerguard and receiver, since the triggerguard is screwed to the butt socket at the rear.

Ample Support

The capacity of the Enfield magazine is 10 — a very useful payload and double that of other combatants’ rifles (except the Garand) and loaded via 5-round chargers from the top. The rounds must be thumbed into the magazine one at a time on sniper rifles, since the scope interferes with the use of the chargers.

When loading the magazine with single rounds, the rim of each successive cartridge must be in front of the one below it or it will hang up and cause a jam. The chargers need to be loaded in a specific fashion to prevent this, but the goal is to have the rims of rounds 2 and 4 above the rims of rounds 1, 3 and 5. How that prevents jams is still a mystery to me, but it works, and that’s all that matters.

The Lee-Enfield was truly an exceptional battle rifle on many levels, and these attributes helped turn it into an even better sniper rifle.

Editor’s Note: Stay tuned for part two next Saturday. Also, please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

59

59