The Soviet Garands?

March 24th, 2020

8 minute read

During the late 1920s, while U.S. Ordnance had John Garand working on his semi-automatic M1 rifle (you can see the author’s article on the history of the M1 Garand here), the Soviets were aggressively pursuing semi-auto and selective-fire rifle designs of their own. This work began to bear fruit during the 1930 rifle competition. Sergei Simonov and Fedor Tokarev’s designs were the best options presented to the Red Army for testing, and further development was authorized to continue.

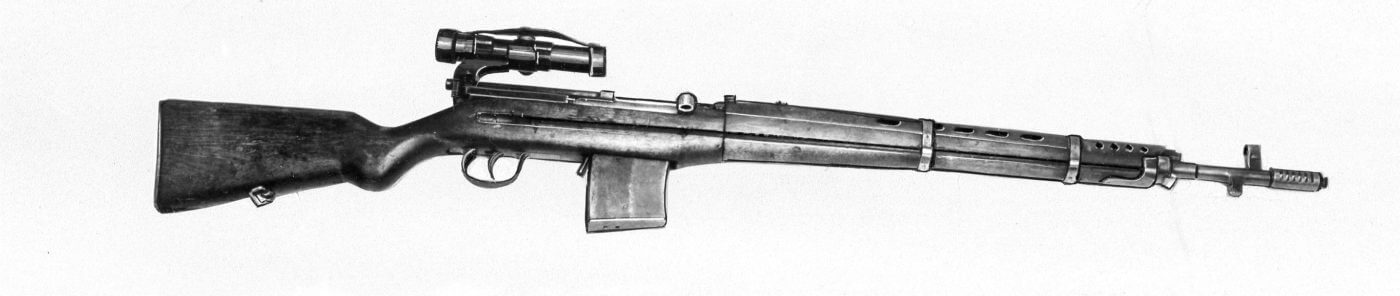

In mid-1935, Simonov’s design took an important step forward. One of Simonov’s early test models of what was called the AVS rifle fired 27,000 rounds and proved itself worthy of production. As a result, the Red Army adopted the select-fire AVS-36 in 7.62x54mmR in 1936.

The new rifle featured certain modifications to Simonov’s original design, most prominently a muzzle brake. The AVS-36 was first revealed to the public during the May Day Parade in 1938. Eighteen months later, the new rifle would be in action during the Soviet invasion of Finland in December 1939.

Even though very few in America noticed, the selective-fire AVS-36 represented a major achievement for the Soviet arms industry. Simonov’s concept was a breakthrough in rifle design, leading Joseph Stalin to comment: “A soldier with a self-loading rifle will easily replace ten armed with manually operated weapons.”

Shape of the Future

John Garand never intended his semi-auto M1 rifle to have full-auto capability. That would come later, with the development of the M14. However, Simonov’s select-fire AVS-36 is frequently compared against the M1 Garand. As a semi-auto rifle, the AVS could be legitimately compared to John Garand’s robust and enduring design.

However, as a selective-fire automatic rifle of that era, the AVS-36 comes up far short when compared against the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR). John Browning’s incredible BAR is a design that stands alone among automatic rifles chambered for standard .30-caliber ammunition (you can see the author’s article on the BAR here).

Maintenance issues abounded with the AVS-36, and ultimately, these issues were never overcome. The firing pin of the Simonov rifle was problematic, and all too often it broke within the bolt. While Soviet troops never lacked for courage, for many the complexities of the new AVS-36 escaped their understanding.

The rimmed 7.62x54R cartridge caused many problems too, particularly with the AVS’ 15-round magazine. In addition, any sustained fire in full-auto would quickly overheat the AVS-36. There were also few extra magazines available to feed it. This deficiency plagued all the early Soviet magazine-fed rifles.

Enter the Tokarev

The Soviet semi-auto rifle design competition continued and during April 1940, the Red Army adopted Fedor Tokarev’s SVT-40. His earlier SVT-38 had been used successfully in the 1939-1940 Winter War with Finland. After some minor modifications were made (including a more reliable magazine release), the improved SVT-40 was brought into service during July 1940.

The venerable bolt-action Mosin-Nagant M1891/30 remained the Red Army’s primary battle rifle, with the semi-automatic SVT-40 often issued to squad leaders in standard infantry, and in greater numbers to elite guards and naval infantry units. The Soviets lost a significant number of SVT-40 rifles during the German invasion beginning in late June 1941.

These were happily taken into German service and given the designation of “Selbstladegewehr 259(r).” SVT-40s can be seen in German service through 1943. Finland also captured many of these rifles and kept them in service until 1958. The Finns sold 7,500 SVT-40s to the U.S. market in the late 1950s through Interarms (of Alexandria, Virginia).

As the SVT-40 was more complex and expensive to manufacture, most production was suspended in favor of the simpler M1891 rifles and ultimately the PPSh-41 submachine gun. Production of the SVT-40 finally ended in January 1945 with a little more than 1.6 million of the rifles made. A sniper variant was produced in small numbers (about 50,000) and outfitted with the Russian PU 3.5x scope.

Another attempt was made to create a selective-fire rifle using the Tokarev design. Production of the AVT-40 variant began in May 1942, and the first examples were issued to the troops in July of that year. The numbers built were small, and its battlefield performance was terrible. Ultimately, AVT-40 production was cancelled by the summer of 1943.

Cold War Turns Hot

When the Korean War began in 1950, the United States found itself in combat, if somewhat indirectly, with the Soviet Union. Even though America had been nominally allied with the Soviets during World War II, the early hot-shooting days of the Cold War showed that we knew comparatively little about the Russian small arms appearing in the hands of enemy troops from communist satellite states.

Some of this lack of awareness of Soviet arms was rooted in a degree of arrogance. After winning World War II, U.S. Ordnance was little concerned with foreign weapons. The war in Korea was an important slap-in-the-face that awakened U.S. intelligence to investigate Soviet small arms.

Some research on Soviet weapons was done, almost accidentally, in the closing days of World War II. U.S. Ordnance and Tech Intel units discovered several Soviet weapons that had been captured in some numbers by the Germans on the Eastern Front, and some that were brought to the West were types that later ended up in combat against U.S. troops.

G.I.s first began to discover Soviet small arms in German hands during the campaign in Normandy, and by the end of the war in Europe, U.S. Ordnance had examined examples of the Soviet TT-33 Tokarev pistol, the PPS-43 submachine gun, the Mosin-Nagant M1891 rifle, the SVT-40 (and AVT-40) semi-auto and selective-fire rifles, the SG-43 machine gun and the PTRS-41 14.5mm semi-auto anti-tank rifle.

Reports from the troops in Korea spurred interest in Russian-made arms. In the March 1951 issue of Popular Science, Editor Perry Githens penned an article titled “How Good Are Russian Guns?”

“The samples captured in Korea show the calculated crudity that is the real secret of Red armament and logistics. For Russian weapons are a literal reflection of the harsh Asiatic philosophy that life is cheap. Where men are expendable, so are guns. And if guns are to be lost in the grinding of war we politely call ‘attrition,’ it is better to lose cheap guns.

“We are justly proud of our Garand, one of the two gas-operated military rifles to be used in any quantity in World War II. The other one was the Tokarev, Models 1938-40. So the Russians were a little ahead of us.

“Like the Garand, the Tokarev is gas-operated. Those who have fired both claim the Tokarev is at least as good as the Garand — maybe better. Certainly the action is visibly simpler in function and manufacture. It boasts a muzzle brake and carries ten cartridges in the magazine to the Garand’s eight. it feels lighter, and the use of stampings and pressings makes it much cheaper.

“No Tokarevs had turned up in Korea by year’s end, and there is argument about their scarcity in World War II. Some think the Russians found them too difficult to make quickly in quantity; others that they were dropped because of variability in ammunition or that they called for a greater investment in manufacture and training than simpler weapons.

“But an interesting possibility is that the Tokarev has been developed further into a light machine rifle and deliberately kept under wraps. it is known to have appeared in its original form as a full-automatic. And, given lighter construction and longer detachable magazines, it could be a formidable weapon.”

About the same time, weapons expert Roger Marsh, writing in Weapons I & Weapons 2 (A Pictorial Survey of Russian Small Arms, 1952) had this to say about the AVS and SVT rifles:

“It is understood that Russian semi-auto rifles, even of the improved Tokarev Model 1940 pattern, were regarded as unsatisfactory in service and were neither manufactured or issued extensively after 1942. Reportedly the fault lay not in the rifles but in Russian ammunition.”

Marsh included a short question at the end of his discussion of the Tokarev rifle:

“But have they really been abandoned?”

Looking Forward…

Both Githens and Marsh wondered about further development of a Soviet semi-auto rifle, a possible refinement of the Tokarev line. Maybe they sensed something coming or heard rumors of new Soviet rifle development.

This would soon come to pass, first with the SKS semi-auto carbine, and soon after with the groundbreaking AK-47 (see also the author’s article comparing the AK and the M14). Neither of these Red Army rifles was a direct descendant of the SVT-40, but Simonov and Tokarev had set the table. When the Soviets developed their 7.62x39mm intermediate round it opened the door for the next generation of enemy rifles that America would face on the battlefield, and eventually see in the hands of allies as well.

…And Back

So how do the “Soviet Garands” stack up against the real thing, the M1 Garand? I think the battel record can speak for itself. While the Russian rifles were admittedly revolutionary, they were never adopted broadly in service as was the M1. Also, the M1 spawned a very direct descendant in the M14 (see the author’s story about the adoption of the M14 here).

And while the Simonov and Tokarev rifles clearly led to the SKS and the AK-47, they were not as directly related as the M1 is to the M14. Additionally, from a consumer/collectors market standpoint, the M1 Garand and the M14 (through the semi-auto, civilian-legal M1A rifle from today’s Springfield Armory) are much more readily available than their Soviet counterparts.

Any way you look at it, the “Soviet Garands” were remarkable firearms well ahead of their time, yet mostly forgotten by today’s shooters. But, maybe they deserve a second look?

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

138

138