Unsung Heroes: U.S. Navy Corpsmen

May 23rd, 2023

7 minute read

Doc Giese was on the verge of throwing a whiny PFC out of his makeshift aid station. We were short-handed as usual, and nothing less than a traumatic amputation was going to keep one of Doc’s Marines from humping along with the rest of us. “I’m not putting you on light duty for ringworm in your scuzzy crotch,” Doc said. He handed the guy a tube of topical ointment and a fistful of aspirin. “I told you last week to stop wearing skivvies.”

Exit one sniveling boot to go pack his gear for a major operation along the Cua Viet River in northern I Corps. We were leaving at dawn the next day and Hospitalman 3rd Class Fred Giese was in hard-ass mode. While he was usually empathetic, he knew a big part of his job as a platoon Corpsman was to preserve our combat power through preventative medical attention as well as treating the wounded everyone expected on this major operation. And Doc Giese took that responsibility seriously.

He viewed the 25 or 30 Marines in the third platoon as his personal little neighborhood medical practice. He knew each of us more intimately than we liked sometimes. He knew about our families and our foibles. He knew our physical and psychological conditions and he kept a wary eye on both at all times.

Where It Counted

Like many other Fleet Marine Force Corpsmen operating with the Marines in Vietnam, Doc had joined the Navy and volunteered for medical training knowing he was likely to end up down in the mud and blood rather than emptying bedpans in a safe and sanitary Naval Hospital. He took the standard ration of harassment about being a squid and a “pecker checker” with good humor and often fired back to remind us that if it weren’t for the Navy Hospital Corps, we’d all be crawling around out in the jungles and rice paddies beset by mange and untreated wounds. He was right.

It was hard to figure Doc sometimes. He told me once that in Medical Corps school it was a crapshoot. In those days most thought if a guy got lucky on graduation, he wound up aboard a ship or in a hospital somewhere. If not, he went to field training and became an FMF Corpsman with the Marines in Vietnam. Fred Giese saw it differently. He had compassion — with a capital C — and a strong desire to see how many lives he could save in a war where so many were being lost every day. And when the rounds started ripping and the shrapnel started slashing, Doc Giese understood he was the man who kept death at bay.

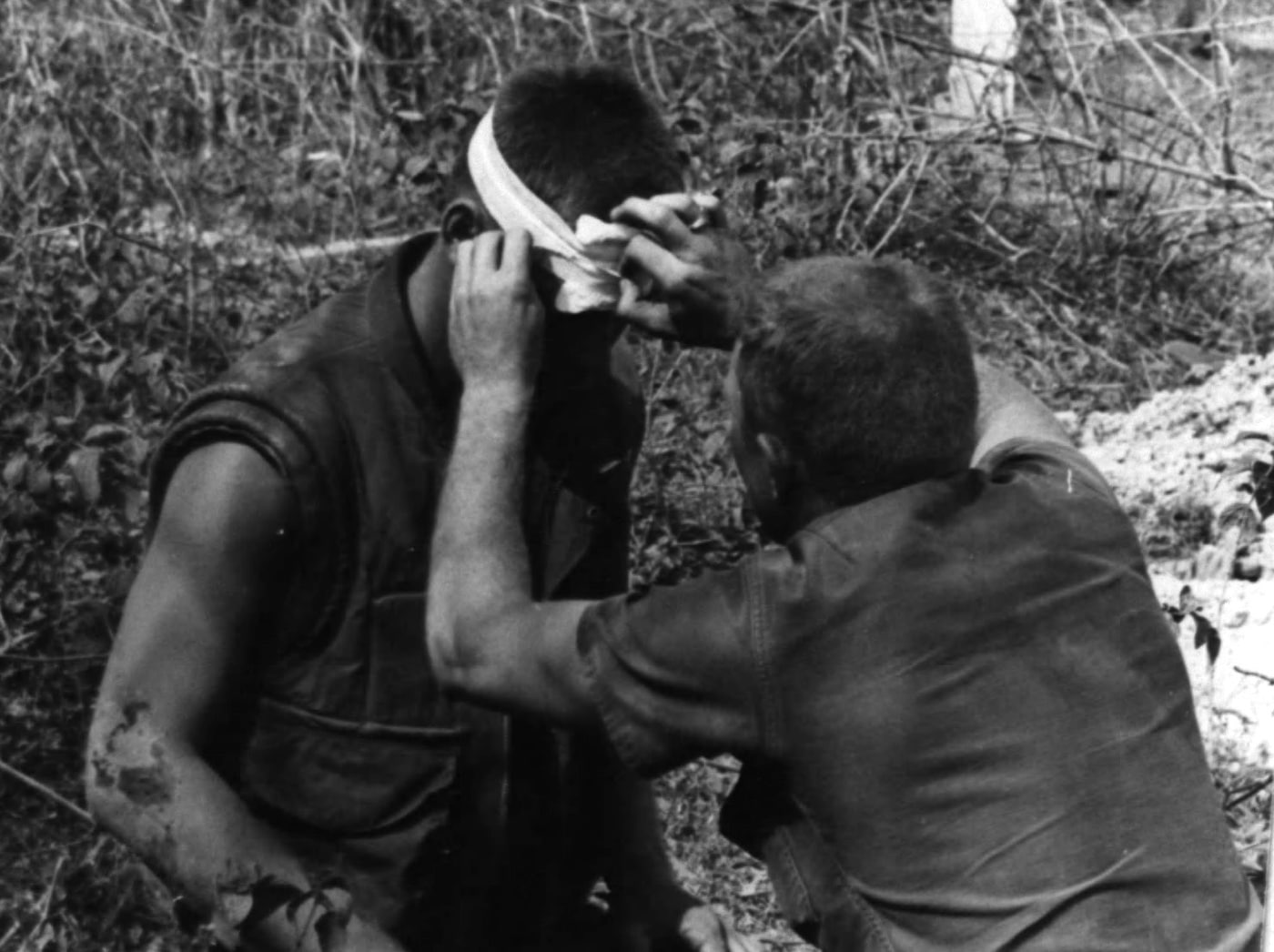

When he couldn’t do that, despite monumental efforts under fire and at great risk to himself, Doc felt our loss perhaps more deeply than anyone else in the outfit. I recall his efforts to save a lance corporal who blundered through a hedgerow and tripped a VC boobytrap, a frag-in-a-can. The detonation blew big holes in his chest and peppered his face with shrapnel. When I crawled forward to lend a hand, Doc had purloined a plastic bag from a spare radio battery and taped it over a sucking chest wound but the wounded man needed more than that. Doc Giese and I traded places sticking grimy fingers into the man’s shredded sinuses in an effort get air into his lungs. We kept him alive long enough for the Medevac chopper to arrive, but later that day we found out he’d died on the flight to the rear.

Doc was devastated. Nothing we said could convince him that he hadn’t personally failed one of his charges. It wasn’t the last time we lost men killed in action, but it was the beginning of Doc’s program of medical training for All Hands. When we weren’t occupied with other field chores, we all attended Doc’s field medical training. He wanted a platoon of his potential patients who could all do rudimentary life-saving procedures. He knew it was only a matter of time until his own luck ran out and he didn’t want us left without someone to keep us from bleeding out in combat. Today that sort of Combat Lifesaving training is formalized SOP in most military units.

Fred Giese had been wounded himself by frags from various incoming rounds a couple of times. He refused to turn himself into the Battalion Aid Station, preferring to ask one of the Corpsmen in the other platoons to dig it out and bandage him up. If he’d been willing to file the paperwork, I figure he would have earned about five Purple Hearts. But that wasn’t his style. He’d seen too many other serious and debilitating combat wounds to make a fuss about a few hunks of enemy shrapnel in his rough hide.

Forced to the Rear

Doc Giese finally ran out of luck one bad day on that very same Cua Viet River op in mid-1968. During our advance across an open, sandy spit of riverside terrain, we were hit by enfilading fire from three NVA machine guns in fortified bunkers. Our point man went down in the opening burst and — as usual — Doc had shrugged out of his pack and charged forward before the Corpsman Up call had even filtered down the line. He blew past me on the run, ignoring rounds ripping past, and started working on the first casualty. That’s when Doc became one. An AK round hit him in the chest. He spun and dropped on his back next to the man he’d been bandaging.

He was alive, curled up behind an old coconut log, digging around in his Unit One medical kit to find a field dressing, when I reached him. Fearing a sucking chest wound, I tried to remember everything he’d taught me about field first aid. The wound wasn’t overly serious, a through-and-through in the right pectoral muscle, but Doc was leaking blood, in serious pain, and clearly a candidate for evacuation as soon as we did something lethal to those enemy machine guns.

Hoping to show him I’d learned a valuable thing or two in his classes, I cleaned the wound, tore open a battle dressing from his kit and wrapped him tightly enough to stop the hemorrhaging. Probably should have left it at that but the morphine syrettes in his kit had caught my eye. We’d all seen Doc administer morphine from those syrettes. They looked like the little travel-size toothpaste tubes you get sometimes as samples. The needle part was covered in plastic that you were taught to remove before injecting the morphine in any large muscle. There was also a foil seal that needed to be pierced before you jabbed the needle in your patient, but I forgot about that.

I probably stabbed Doc Giese in the thigh about five or six times before I figured out why the morphine refused to inject. At that point, he was digging around with his good arm, trying to draw his .45 from its holster. I told him to relax, the guys up front were dealing with the NVA, he wouldn’t need to help with his pistol. “Hell with the NVA,” Doc groaned. “I’m gonna shoot you before you kill me with that morphine syrette.”

HM3 Fred Giese made the chopper later in the day, wound up on a hospital ship, and bitched when they told him his war was over, he was heading back to The World. We stayed in touch until he died of a heart attack about three years ago.

He was just one of some 10,000 U.S. Navy Hospital Corpsmen who served with Marines in Vietnam. He managed to avoid being one of the 600 or so killed in action but he was one of the 3,000 wounded in combat trying to save their Marines. For that, all of us who are alive today and wearing the Purple Heart, owe Doc Giese and his Medical Corps shipmates an eternal debt of gratitude.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

613

613