Was the M1903A4 Sniper Rifle No Good?

April 26th, 2022

6 minute read

Like many combatant nations, the United States entered World War II without a specialized sniper rifle. Also, the U.S. Army had no sniper school during WWII and, despite its traditional development of marksmen, specific sniper training was conducted in the combat zones. Even so, the Arsenal of Democracy was quick to respond with a sniper rifle, although it turned out to be neither the weapon that most troops expected, and one with which few were happy.

The Model 1903A4 sniper’s rifle was born of the newly created M1903A3 rifle, a simplified version of the classic M1903, designed to speed production and reduce costs. The M1903A4 was standardized on January 14, 1943, and production ramped up by the middle of the year.

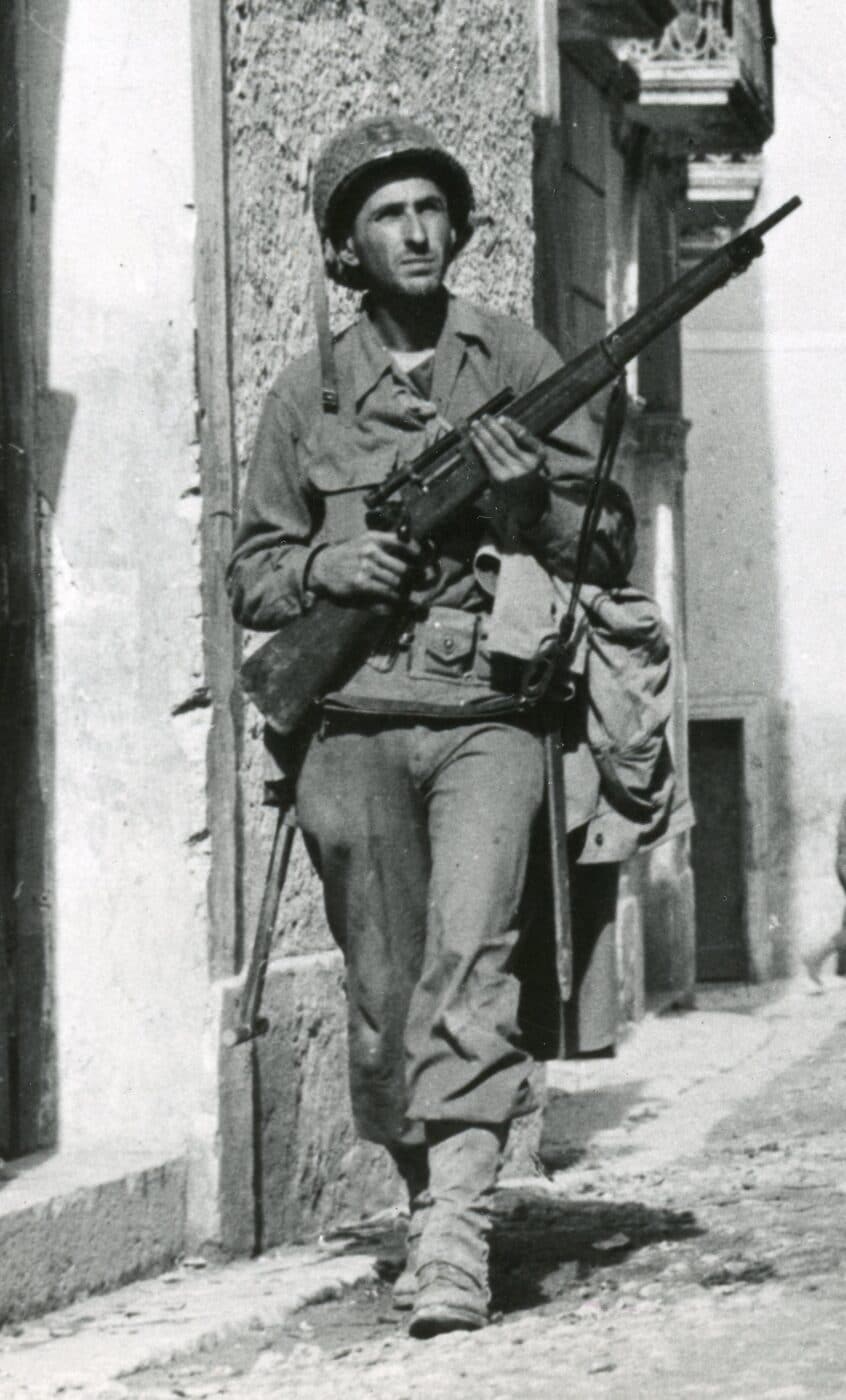

The M1903A4 was used in small numbers during the latter part of the North African campaign and the invasion of Sicily. By the beginning of 1944, American snipers with M1903A4 rifles were active in the rugged Italian terrain, a combat environment that was ripe with sniping. Meanwhile significant numbers of the M1903A4 rifles were stockpiled for the upcoming invasion of France.

Less Than Expected

On the surface, this would appear to be the normal progression of yet another American military firearm success story. Unfortunately, that would not be the arc of the M1903A4’s history. While most purpose-built sniper rifles are highly refined precision instruments, the 03A4 seems rather crude by comparison.

American troops were skeptical of the new weapon, particularly after practicing shooting revealed the rifle’s unimpressive, just-above-average accuracy. The addition of a telescopic sight to an ordinary battle rifle might make it look the part, but only its battlefield performance will distinguish it as a sniper’s weapon.

In his excellent book Shots Fired in Anger (Small Arms Technical Publishing Company, 1947) Lieutenant Colonel John B. George, gives us a combat infantryman’s assessment of the M1903A4 in the PTO and CBI:

We were not issued sniper rifles in any form in time to use them on Guadalcanal. The models sent out later with a Weaver scope and two-groove barrel could hardly be called more than reasonable excuses for sniper arms. The most that could be said for these outfits is that perhaps they did give a few men the advantage of a telescopic sight (of very limited optical value however), and perhaps they may have accounted for a few Germans and Japanese who might otherwise not have become casualties.

… Since the gun on the range proved to be such a sad sort of a cluck, we didn’t make much use of it in Burma, where we finally did get it. I saw it used a few times under conditions which called for any old kind of rifle — shooting Japanese across a fifty-yard-wide stream. In this perhaps it did a little better than an ’03, not quite so well as a Garand. The Weaver scope, plenty good enough for sporting use, just wasn’t the instrument to give to a sniper at the front. An M1, with its increased rate of fire, would be much better for sniping than the so-called sniper rifle.

Shots Fired in Anger (1947)

George identifies the root cause of the issues with the M1903A4, which go far beyond the basic mechanics of the rifle itself:

It was obvious from the outset that little was being done (on proper staff levels) to develop a good sniper weapon or even to train snipers. The M1903 sniper rifle, WWII version, was a substitute measure — and a poor one at that. It placed a delicate and optically inadequate weapon of only moderate accuracy in the hands of troops untrained in its use and even that at a very late date. What we needed was a good, sturdy scope on the M1, and we didn’t get it until the war was over.

Shots Fired in Anger (1947)

An Unstable Foundation

Most experts agree that the basis for the new U.S. sniper rifle was presumed to be a “National Match” version of the finely crafted M1903A1 rifle. Unfortunately, the “03A1” was no longer in production by the time rifles were needed to construct the M1903A4, and thus the no-frills M1903A3 was chosen.

A litany of complaints about the M1903A4 came from the combat troops, most of them concerning the M73B Weaver scope, which was judged to be “optically inadequate”, and not rugged enough for combat duty. Due to the low position of the scope above the receiver, the rifle could only be loaded with one cartridge at a time.

Special ammunition was neither needed nor provided for the M1903A4. Lt. Colonel Jones describes the practicalities of sniping in the Pacific Theatre:

Ammunition was not such an important factor when it came to sniping in the jungle. Shooting at such short ranges as we did provided no real test of accuracy and made no great demands for super-refined target type loadings. The ordinary M-2 would shoot well enough for most sniping purposes.

The Weaver scope offered very poor performance in low-light conditions, and was prone to fogging. In humid environments, particularly in the Pacific Theater of Operations (PTO) and China/Burma/India Theater (CBI), moisture and mold seeped into the tube, blurring the lenses and obscuring the cross-hairs.

Another troubling factor was that the scope was fragile, and its windage screws were too easy to damage or lose, and far too difficult to fix or replace. Snipers claimed that the Weaver scope would not “hold zero” if removed from the rifle and then returned to position. Without the scope, the M1903A4 was completely sightless, as no iron sights were fitted.

Conclusion

The very root of any sniper rifle is its inherent accuracy, and in this regard the M1903A4 was no better than any ordinary rifle. America’s experiment with a low-cost Springfield produced a fully serviceable bolt-action battle rifle, but the bargain-basement sniper’s rifle (approximately $64 each) was of questionable value.

Even so, availability is often a great capability, and while the M1903A4 is not ranked among the great American firearms (and that is a particularly distinguished group), it was available when our troops needed it, useful even if never popular.

A little more than 28,000 M1903A4s were produced, all of them at Remington Arms. Production wrapped up in the summer of 1944 in anticipation of the new M1C sniper’s rifle. The M1903A4 was widely distributed to U.S. Army units through 1944, and some also went to the Marines by the end of the war in the Pacific. The M1903A4 continued on in service into the Korean War and some even survived in Army inventory (albeit in the farthest corners of the arsenal) into the 1970s.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

273

273