What Is .223 Wylde?

July 11th, 2022

8 minute read

Not long after the U.S. Army approved the M16 for service rifle matches in the 1990s, gunsmith Bill Wylde of Greenup, Illinois, decided to fashion a rifle chamber that would manage the pressures of the frisky 5.56 NATO but deliver the superior accuracy of bolt rifles bored for the .223 Remington.

The .223 Wylde is not a cartridge. You’ll not find .223 Wylde ammunition. The .223 Wylde is in raw form a series of dimensions. In finished form, it’s a chamber with those dimensions.

A review of the .223 and 5.56 NATO makes Bill Wylde’s inspiration easier to understand. These twins date to 1957, when the .223 emerged as an experimental cartridge for the new AR-15 infantry rifle. Gene Stoner and Bob Hutton at Guns & Ammo magazine paired a 55-grain bullet with a case slightly longer than the .222’s. Given an exit speed of 3,250 fps, that spitzer met the Army’s requisite of supersonic flight to 500 yards.

The new load was adopted in 1964 as the 5.56mm Ball cartridge, M193, and accompanied U.S. forces to Vietnam. In 1980 it earned a nod from NATO, which substituted an FN-designed 62-grain SS109 boat-tail bullet at 3,100 fps. Its superior ballistic coefficient brought more and harder hits at distance. Faster 1-in-7 rifling twist maintained accuracy. The U.S. Army called this load the M855. Case length in millimeters established the name: 5.56×45 NATO.

Remington led the rush to chamber for it in sporting rifles. The .223 owed much to the popularity of the .222 Remington, introduced in 1950. The “triple deuce” dominated at Benchrest meets, and was soon the darling of ‘chuck, crow and fox hunters. While the .223’s 1.760-inch case was only .060 longer than the .222’s, the .223’s had a short neck and held 20 percent more powder. Springfield Armory and Remington had rejected a 1.850-inch hull as a trifle long for the AR-15’s action. In 1958 it found a commercial home as the .222 Remington Magnum, first offered in the Model 722 bolt rifle.

Are They the Same?

Before diving into an exacting description of what the .223 Wylde is, let’s take a look at the .223 Rem and 5.56 NATO.

It’s easy to see why the .223 and 5.56×45 NATO are commonly thought to be interchangeable, if not identical cartridges. (Be sure to read our .223 vs. 5.56 article.) Listed case dimensions are the same, and each will fire in chambers bored for the other. But there’s more to the tale, and “the rest of the story” is why the .223 Wylde is important.

Numbers can enlighten. SAAMI specifies .223 Remington loads be held to 55,400 Copper Units of Pressure, while service loads for the 5.56 NATO can generate 58,500. CUP measure has deep roots and is taken this way: A copper cylinder of fixed dimensions is placed over a hole in the barrel wall above the chamber; firing a shot compresses the copper; a measure of the compression converts to units of pressure.

More recently, a transducer or strain gauge is used to register pressure over small slices of time, yielding a pressure curve in pounds per square inch. CUP and PSI values are often carelessly traded, one for another, but they are not the same! Nor is there a formula to convert one to the other. Maximum average pressure for the .223 in PSI is 55,000. It’s 62,000 for the 5.56. Not the neat mathematical relationship you might expect, given their CUP values! Even if a handy conversion formula existed, the location at which these measures are taken on the .223 and 5.56 cases preclude easy comparisons.

Bear with me. In SAAMI’s lab, pressure is taken near the middle of the case. NATO hews to the C.I.P. or European practice of tapping pressure at the case mouth. Mid-case pressure for a 5.56 load at the 62,000-psi ceiling is 60,000 psi… Lost in this numerical fog, you’re left with a pretty simple conclusion: Standard 5.56 loads are frothier than those for the .223. This doesn’t mean 5.56 cartridges fired in a .223 chamber will shred the barrel — only that .223 rifles aren’t required to brook proof pressures at 5.56 levels. Many .223 rifles can easily withstand the battering of 5.56 rounds, and function smoothly — just as Uncle Willard’s weary ’06 submits to handloads hurling 150-grain bullets at Mach 3.

Gas from the burning powder builds quickly to uncork a bullet. Its release puts a small dimple in the pressure curve; but the bullet’s easy travel through the throat is over in a trice. When rifling bites into its shank, the bullet slows; gas must suddenly work to keep it moving. There’s a pressure spike. You’ll see that spike when measuring pressure in CUPs only if it exceeds the pressure that started the bullet, as a copper crusher shows only the highest pressure. Theoretically, you won’t know which peak registers, or consequently, if it’s within SAAMI or CIP spec.

Visible Variables

More obvious early on was the difference in accuracy between rifles chambered in .223 and 5.56. When Remington began boring barrels and developing loads for the .223, it specified a shorter throat and steeper leade than was standard for infantry rifles. A rodent out yonder begged precision not required on the battlefield. The soldier’s priority was function. His rifle had to cycle reliably under harsher conditions than endured by most hunters. No matter the dust and debris, the water, snow and ice, the palm-blistering barrel temperatures, the condition of the ammunition, a soldier had to have a gun that would run! The generous throats ensuring he could weren’t much help herding those bullets into tiny knots.

Are 5.56 rifles beefier? No. They operate comfortably with ammo that generates higher pressures than does the .223 because chambering reamers for the two cartridges differ.

Base to mouth, the two cartridge cases are identical. They headspace the same, too. That is, from bolt face to point of chamber contact with the case shoulder (datum line), headspace specs are the same. Gunsmiths check headspace with “go” and “no go” gauges. A “go” gauge is typically .004 to .006 shorter than a “no go” gauge for rimless bottle-neck cartridges. The bolt should close on a “go” gauge but not on a “no go” gauge. Usually, if the bolt closes on a “no go” gauge, the barrel is best set back a thread, then re-chambered to achieve proper headspace. However, many chambers that accept “no go” gauges are still safe to use. A “field” gauge has been employed to check these (mostly military) chambers. It’s about .002 longer than a “no go” gauge.

Dimensional drawings show chambering reamers for the .223 and 5.56 are almost identical to the fourth decimal point over most of their length. Thus, the chambers are as evenly matched:

| .223 Rem | 5.56 NATO | |

| Diameter at shoulder | .3553 | .3553 |

| Shoulder-to-neck angle | 23 degrees | 23 degrees |

| Neck diameter at shoulder | .2550 | .2551 |

| Mouth diameter | .2540 | .2540 |

But between the chamber mouth and full-depth rifling in the bore, these chambers differ.

| .223 Rem | 5.56 NATO | |

| Throat length (freebore ahead of mouth) | .040 | .070 |

| Throat diameter | .2240 | .2265 |

| Leade angle (from throat to full-depth rifling) | 3 degrees, 10 | 1 degree, 13 |

| Total throat and leade length | .103 | .339 |

Where It Counts

No matter the load, a .224-diameter bullet has less wiggle room as it leaves the case mouth in a .223 chamber than when launched in a 5.56. And it meets full-depth rifling sooner. Pressures in the 5.56 case, higher by spec, would stay higher or peak again more dramatically in the relatively short, tight .223 throat than in the generous 5.56.

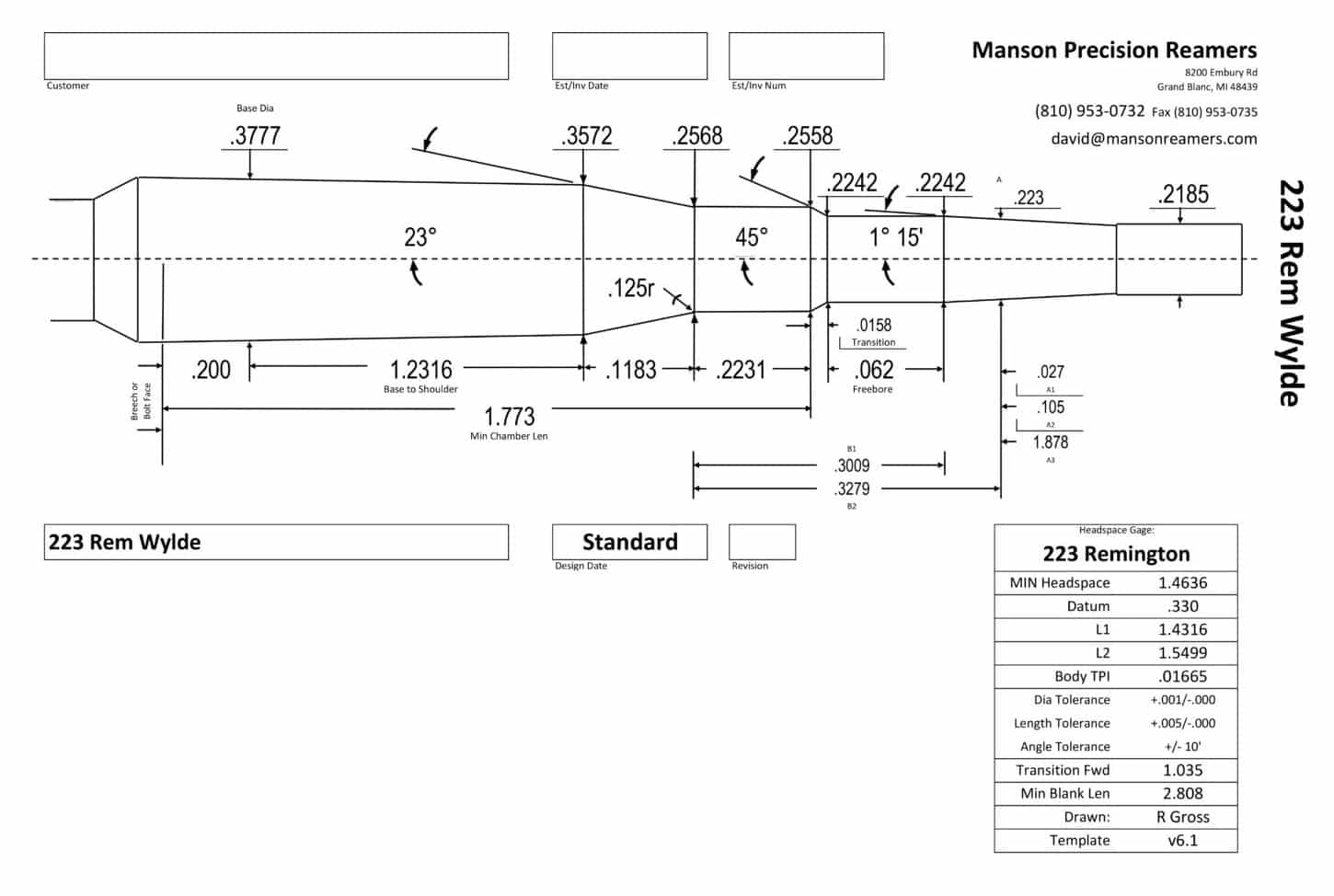

Bill Wylde figured few shooters enjoyed fretting over leade angles, secondary pressure peaks and fourth-decimal chamber dimensions. So, he came up with a reamer that enabled any rifle to cycle breezily with both .223 and 5.56 factory ammo and deliver the accuracy bolt-rifle shooters got with their .223s. A Wylde reamer from Pacific Tool and Gauge or Manson Reamers looks like this up front:

| Throat length (freebore ahead of mouth) | .078 |

| Throat diameter | .2242 |

| Leade angle (from throat to full-depth rifling) | 1 degree, 15 |

| Total throat and leade length | .307 |

Freebore diameter, at .2242, is essentially equal to that of the .223. But at .078, the length of this section is even greater than that of the 5.56. Throat-and-leade length almost matches the 5.56’s. The leade angles are nearly identical. The Wylde’s barely-over-bullet-diameter freebore keeps a tight leash on bullet wiggle upon exit, while a long throat section and gentle leade angle keep pressures at bay.

Incidentally, a Wylde chamber is a bit more generous behind the throat, too: .3572 diameter at the shoulder, .2568 diameter at the neck, .2558 at the mouth. Why? “Maybe to clean up chambers,” suggested a friend. This explanation is appealing not just because it’s simple. It also makes sense. A Wylde chamber can of course be cut in a new barrel. But it can also be reamed from a .223 chamber. Reamer wear, also variations in the practices and workmanship of tooling operators, can produce chambers out of spec, even out of round. The first job of any chambering reamer — like the “do no harm” caveat for physicians — is to ensure any change is positive and doesn’t simply compound a problem.

Conclusion

This review owes much to several smart, experienced people in the shooting industry: rifle-maker D’Arcy Echols, Dave Kiff at Pacific Tool and Gauge, barrel-maker John Krieger, Dave Manson (Manson Reamers), also ace gunsmiths Patrick Sweeney and Fred Zeglin (4D Reamers). Errors are mine.

I’ll own most subsequent confusion around the Wylde chamber too, but not all of it. Some must be laid to reckless use of “throat,” “leade” and “freebore” by the brethren, and to variation in measurements. Tolerances also contribute, one reamer, lathe, barrel and operator to the next…

Few truly useful ideas hinge on accurate measures to the fourth decimal. Bill Wylde’s does not.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

243

243