When the SKS Faced the M14

May 5th, 2020

9 minute read

The end of World War II brought on the beginning of the Cold War. One would think that after the incredible slaughter seen in the conflict, particularly among the nations of Europe, that the military forces of the world would take a break. As it turned out, the period immediately following World War II was one of the most fertile periods for weapons development — particularly small arms.

The Red Army had managed to defeat the Wehrmacht despite their chronic shortage of rifles throughout the war. The Soviets held on through their darkest days, using Mosin-Nagant M91/30 rifles of pre-World War I vintage, along with the associated carbines (the M1938 and the M1944) created from that long-lived combat rifle. Many thousands of Axis rifles (most notably the German Kar 98k) captured on the battlefield were issued to Soviet second-line and guerrilla units.

During the late 1930s, the Soviets had also developed a semi-automatic battle rifle — and after several attempts (including the select-fire AVS-36 and the AVT-40) the SVT-40 was accepted into service (to learn more about the AVT and SVT rifles, click here). Chambered in 7.62x54mmR and featuring a 10-round detachable box magazine, the SVT-40 was a good rifle, but one that proved too fragile and complex for typical Red Army soldiers. After about 1.5 million SVT-40s were built, the production lines at Izhevsk were returned to making M91/30 bolt action rifles.

In May 1945, as the Red Army soldiers stormed through Berlin, the great majority of the troops were armed with submachine guns, either the PPSh-41 or PPS-43. Sometimes entire units were equipped with these fast-firing SMGs, pouring out tremendous amounts of lead at short range. The Soviets were willing to pay the bloody cost in human resources to get in close.

The PPSh-41 was made in huge numbers (five million-plus by the end of the war) and coupled with about two million of the PPS-43 SMGs the Soviets had plenty of cost-effective, albeit short-range firepower. Red Army planners knew that they needed more — more firepower, more range and more consistency. By 1944 they were engaged in developing a semi-automatic carbine rifle designed to leverage a new intermediate cartridge. This would become the SKS.

Battlefield-Born

During late 1943 and early 1944 the German “Sturmgewehr” MP43 and MP44 automatic rifles made a huge impression on the Russians. The radical new design featured controllable full-auto firepower and low-cost production and was centered around a new intermediate cartridge, the 7.92mm “Kurz.” The round balanced performance between a pistol-caliber SMG and full-powered rifle.

The Soviet armaments commission saw the value in this new cartridge and set out to design its own. It planned to use it across a broad range of infantry arms, including a semi-auto carbine, a rifle with select-fire capability, as well as a light machine gun. The new Soviet cartridge was designated the M43, and this became the now-famous 7.62x39mm round used around the world. But what rifle would fire it? While your first thought is probably the AK-47 (to learn more about that rifle, click here), there was one before, created by Russian arms designer Sergei Simonov.

Simonov’s straightforward self-loading carbine was designated the SKS-45, and a small number of pre-production examples were tested in combat in the last weeks of World War II. Refinements were made and the SKS was officially adopted by the Red Army in 1949.

In appearance the SKS is a conventional style semi-automatic rifle, with a wood stock. Suitably rugged and simple to meet the needs of the Bolshevik infantry masses, the SKS is a very capable rifle. It maintains the traditional wood stock of pre-WWII semi-auto rifles, but it is shorter and handier. It couples the intermediate M43 round with a barrel long enough to make it accurate beyond 200 meters.

There is no provision for full-auto fire, and all SKS rifles have a built-in bayonet (either flat blade or spike types). The integral ten-round magazine can be loaded with individual rounds or by using stripper clips. At 8.5 lbs., there is much here for the infantryman of the era to like. But the SKS was simply marking time as the Red Army waited for their one true love: the aforementioned AK-47.

Unfairly Short-Lived?

As good as the SKS was, the Soviets were preparing a game-changing rifle that would remake the small arms world. As Mikhail Kalashnikov’s AK-47 was molded into shape, the SKS served as the Red Army’s primary battle rifle from 1949 until about 1955. After that, the SKS was held in reserve with second-line and militia units in the USSR into the 1980s. In Russia, the SKS was built at the Tula and Izhevsk arsenals from late 1945 until early 1958, with total production in the USSR totaling more than 2.5 million.

Millions more were made in Communist China and in many of the Warsaw Pact nations. East Germany, Poland, Yugoslavia, Romania and Albania all built their own SKS carbines. All told more than 15 million SKS carbines have been made.

The SKS truly found a home in the People’s Republic of China. Introduced in 1956, the Chinese Type 56 Carbine fit the needs of the People’s Liberation Army exceptionally well. The Chinese infantry preferred the greater accuracy and range of the SKS to the AK-47 (in China the locally produced AK-47 is also called the “Type 56,” apparently just to confuse the rest of the world).

The Type 56 soldiered on in Chinese service until well into the 1980s, and still exists today as a battle rifle for reservists and militia units. A unique Chinese SKS variant was the Type 63 selective-fire rifle developed by that country. The Type 63 uses special 20-round magazines (similar but not interchangeable with any AK-47 magazines) and cycles at about 700 rounds per minute. Ultimately unsuccessful, the Type 63 does show how dedicated the Chinese were to the SKS design.

Identifying the SKS

As far as the U.S. military was concerned, the SKS came and went without a lot of fanfare. This is not to imply that the NATO partners didn’t care about the SKS, but my searches of early Cold War-period documentation provide little discussion or description of the Soviets’ new standard battle rifle.

For example, in the June 1954 Army Publication “Materiel in the hands of or possibly available to the communist forces in the Far East” (Headquarters Army Forces Far East, Military Intelligence Section) there is no specific heading dedicated to the SKS, but there is a mention of what is probably the SKS on the Tokarev rifle (SVT-40) page:

7.62mm semi-automatic rifle, M1940 “Tokarev” (Soviet)

“A semi-automatic carbine version of this rifle also has been produced.”

This quick description is a reasonable assumption based on what NATO intelligence knew at that point. As far as is known, the SKS did not appear on the battlefields of the Korean War. British and French troops ultimately captured SKS carbines from the Egyptians during the Suez Crisis of October/November 1956.

The SKS also showed up in the hands of Soviet troops during the Hungarian Uprising of October/November 1956 (this is also the first time the AK-47 appeared in combat). These incidents provided the first significant intelligence on the SKS prior to American troops capturing example in the early part of the Vietnam War. Even so, the SKS tended to be overlooked when compared to attention given to the AK-47.

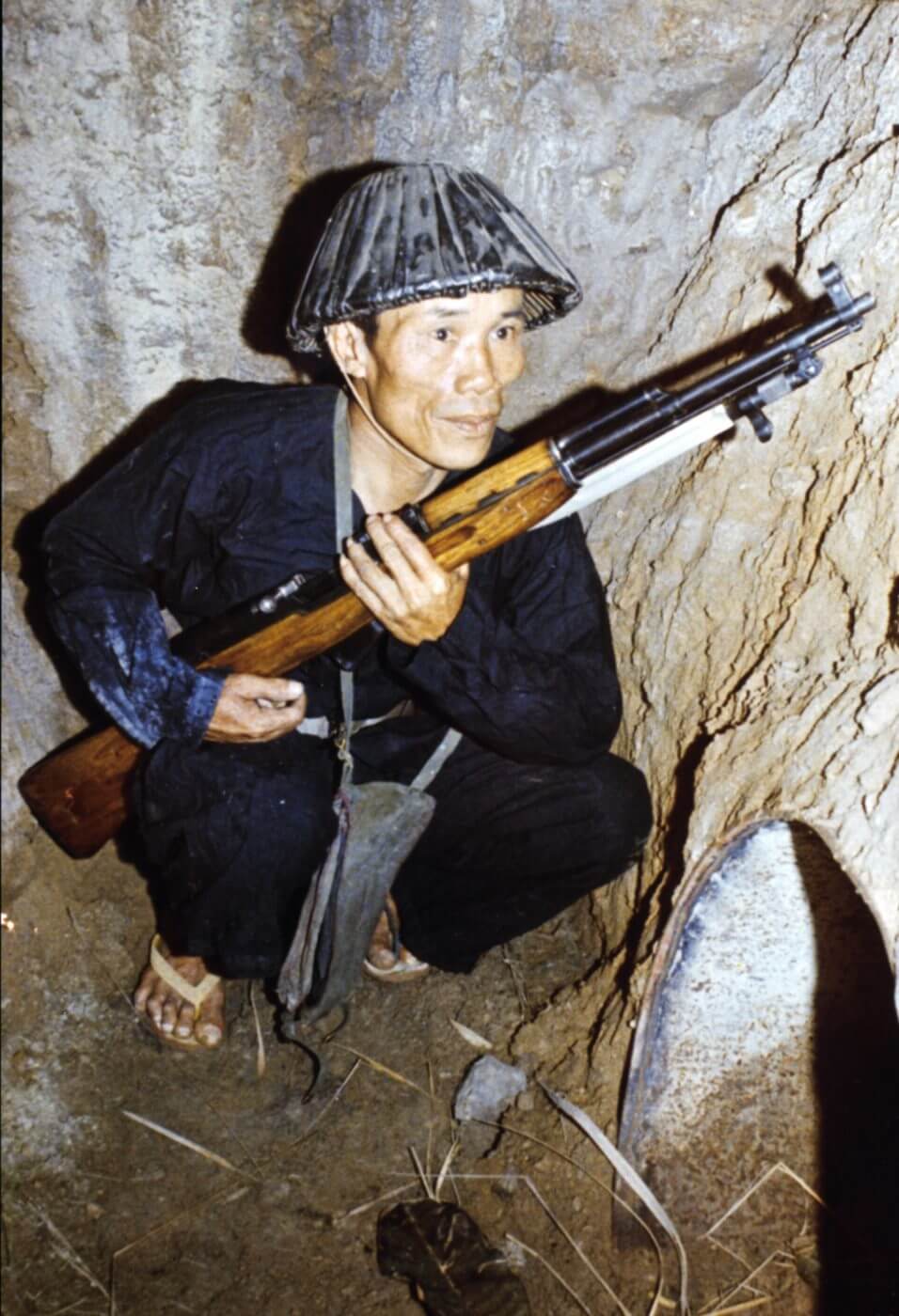

U.S. troops in Vietnam began to encounter the SKS in the hands of the Viet Cong. They found it a worthy opponent, and the SKS quickly became a popular war trophy. A June 1966 U.S. Army “Staff Film Report” documents the arrival of Brigadier General Glenn D. Walker of the 25th Infantry Division at Landing Zone Oasis near Pleiku after the major action there. The film shows General Walker observing a display of captured VC weapons, including an SKS and an AK-47. The SKS was finally getting some attention, primarily from the troops that faced it.

The Simonov rifle even made it to Hollywood in the 1968 movie “The Green Berets” (directed by Ray Kellogg and John Wayne) as the SKS is shown in a scene about a public briefing on Communist weapons in Vietnam. But celebrity, even among firearms enthusiasts, was elusive.

In the “Guide to Combat Weapons of Southeast Asia,” produced in 1971, the SKS is described as:

Soviet 7.62mm Semiautomatic Carbine Model SKS (Chinese Communist 7.62mm Carbine Type 56)

The SKS, an obsolescent weapon in the Soviet forces, has been widely distributed throughout the Communist world and some neutral countries. Recognition features consist of a permanently attached folding bayonet, a protruding magazine, a high front sight, and a top-mounted gas cylinder. The ChiCom version differs from the Soviet SKS mainly in markings. Late ChiCom Type 56 rifles are equipped with folding spike bayonets rather than the flat-bladed one shown.

Versus the M14

Under closer examination, the SKS and M14 (to learn about the M14 in combat in Vietnam and beyond, click here) have a lot in common. Both were born in a post-World War II environment to serve in armies that had been victorious in the greatest conflict of all time. Both rifles leveraged existing technology and were based in successful designs. Both also used a new cartridge (at the time of their development). Ultimately, both the SKS and the M14 had relatively short careers as their army’s primary battle rifle.

Some observers have claimed that the SKS was obsolete as soon as it was introduced, but this is simply not so. Similar ridiculous claims have been made about the M14. These overly critical assessments fail to take into account the combat environment that both rifles were intended to serve in — and both were perfectly suited to the European battlefields where the Third World War was expected to be fought.

As it turned out, the M14 and the SKS would face each other in the guerrilla war environment of Vietnam. Both weapons performed well — their 7.62mm ammunition was powerful enough to muscle through jungle cover and accurate enough to deliver results at range. But commitments to next generation rifles had already been made, and the SKS and M14 soon gave way to the AK-47 and M16. Their wood and steel construction was replaced by folding metal stocks and polymer parts.

Even so, the SKS remained the prime battle rifle of the massive Chinese People’s Liberation Army for more than 30 years. In Europe, where the M14 remained in service longer than in Southeast Asia, riflemen equipped with M14s or SKS carbines stared each other down from opposite sides of the Berlin Wall, ready for the moment that the Cold War turned hot. Thankfully, that never happened.

And today, you can find both SKS rifles and semi-automatic versions of the M14 rifle — in the Springfield Armory M1A — being fired side-by-side at American ranges. This is quite a testament to both the rifles’ resiliency as well as to the post-Cold War world in which we now live.

Editor’s Note: Be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in!

Join the Discussion

Featured in this article

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

271

271