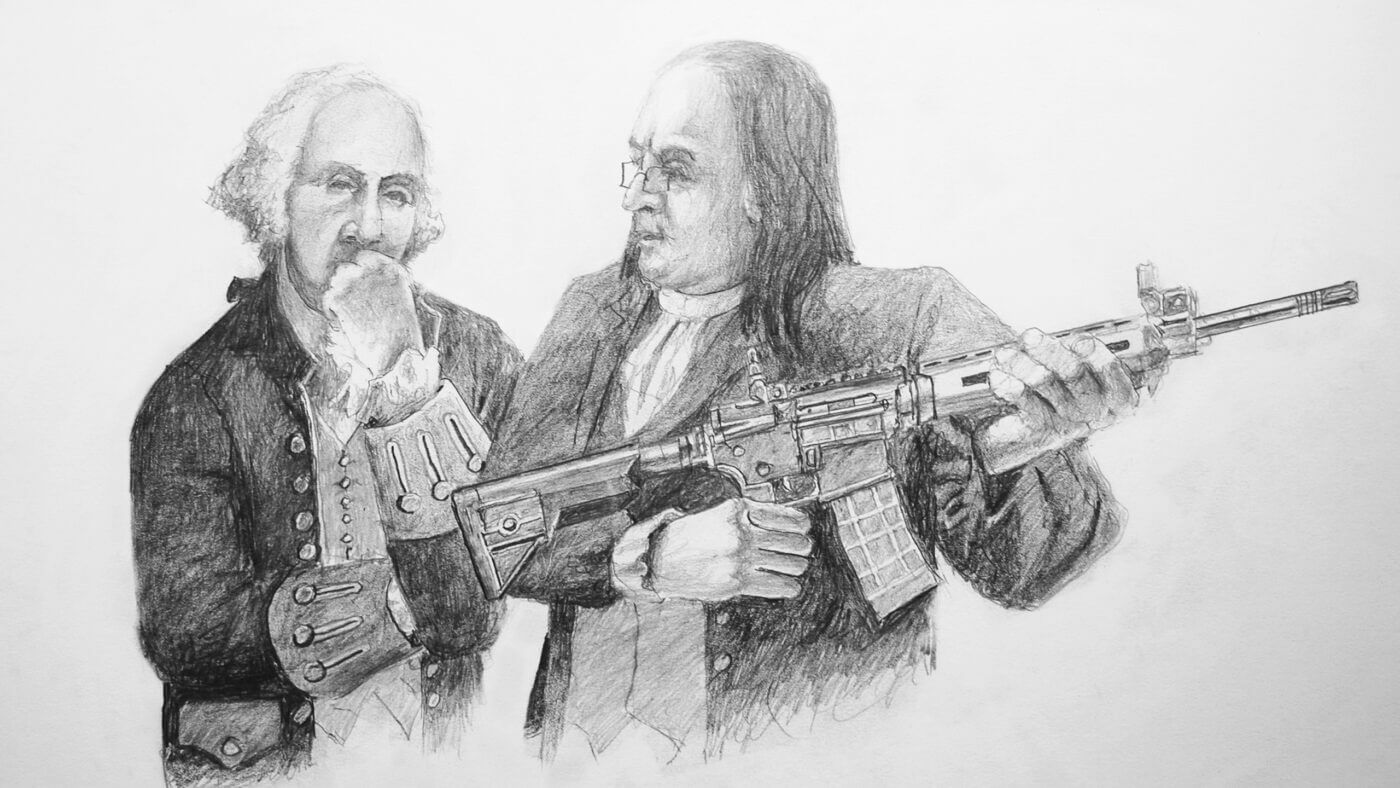

Would the Founding Fathers

Have Banned “Assault Weapons”?

March 25th, 2021

6 minute read

These days, we hear a lot from gun control advocates about how the framers of the United States Constitution would not have allowed citizens to own an “assault weapon”, as the firearms they knew of were much simpler designs.

Firstly, let’s address the term “assault weapon,” and how it is misapplied to many perfectly legal, semi-automatic-only firearms. In reality, an “assault rifle” is a select-fire firearm that is capable of firing more than one round with a trigger press (to learn the history of the first true “assault rifle”, the German StG44, click here). While select-fire firearms can be possessed by civilians, the requirements are very restrictive (to learn about “NFA” and what it means, click here).

However, the semi-automatic firearms often mischaracterized as “assault weapons” are simply guns that fire one round per press of the trigger and are used in a broad range of roles by shooters from plinking to hunting to self-defense.

But, let’s now address the question of how the Founding Fathers would have felt about the types of repeating firearms available today and protected by the Bill of Rights’ Second Amendment. In fact, there is a very strong argument that they were already familiar with firearms of this type — even before they drafted the Constitution.

Ahead of Its Time

To tell this story, we need to go back to Philadelphia in the 1770s and consider Joseph Belton, an inventor and gunsmith. He had an idea for a new rifle in the early days of the American Revolution, and while his specific rifle design was new, the concept it was based upon — being able to fire more than one shot without reloading — was not.

Arms equipped to fire multiple shots long predated Belton’s idea. One concept was a combination wheellock/matchlock firearm from 1580 that could hold sixteen shots. Another style used what was known as the Lorenzoni mechanism, which enabled users to discharge their arms a handful of times before needing to reload.

Belton claimed to have devised a new form of flintlock musket that was capable of firing multiple times before needing to be reloaded. After the gun had fired its consecutive loads, it could then be reloaded individually like all other traditional muzzleloading weapons of that time.

The commonality between all of these repeating arms is that while they set the user up for multiple, consecutive shots. Sound familiar?

An Opportunity

Belton wrote to Congress about his new invention on April 11, 1777, letting them know he could be available to demonstrate it to them at any time.

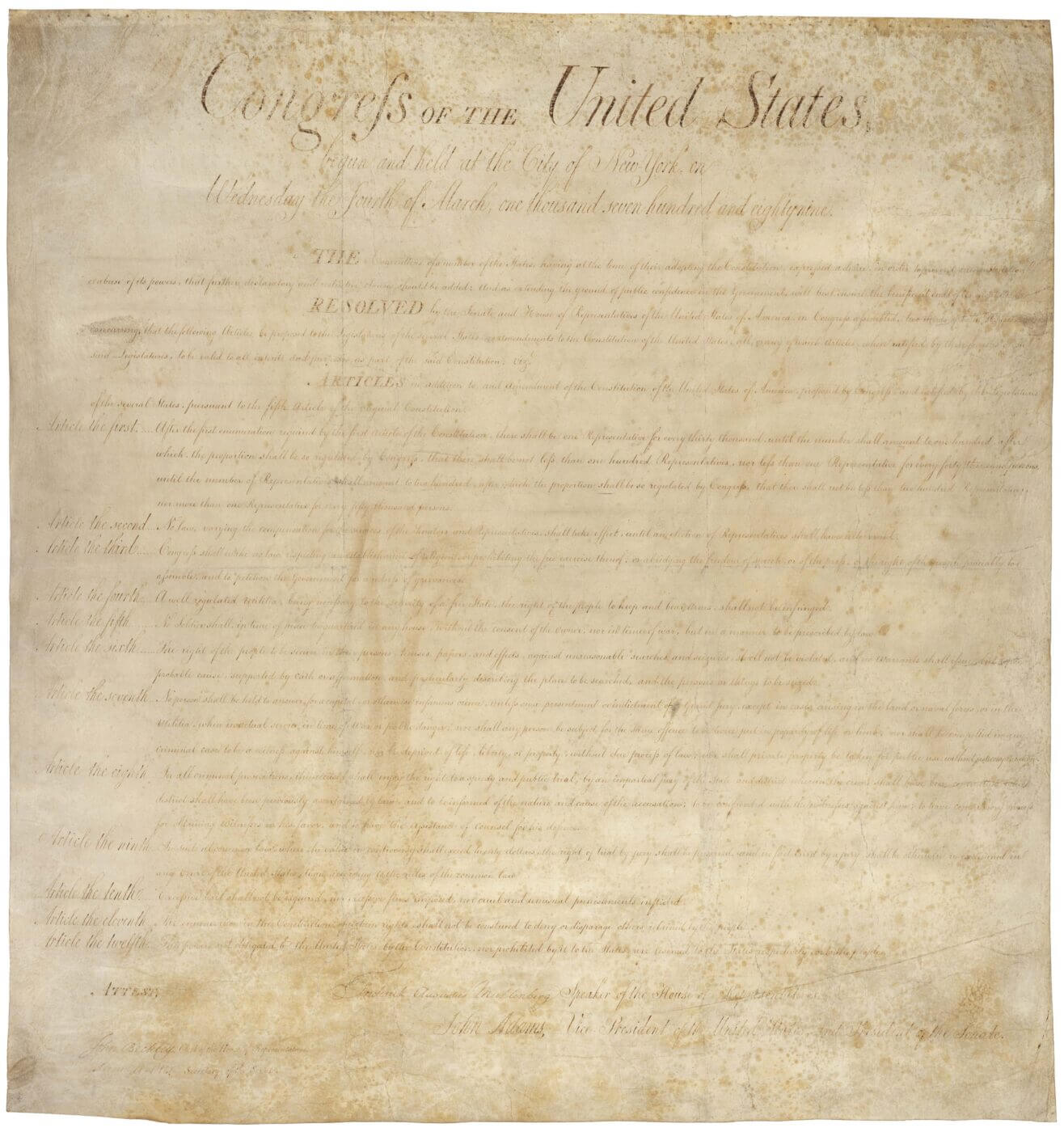

Intrigued by Belton’s claim, Congress ordered 100 examples of his “new improved gun.” They authorized him to oversee the construction of new guns, or alteration of existing guns, so that they were capable of discharging eight rounds with one loading and that he “receive a reasonable compensation for his trouble, and be allowed all just and necessary expences [sic].”

On May 7, Belton replied to Congress with his terms regarding what he felt to be reasonable compensation. He wanted to arm 100 men with his invention, demonstrate the capabilities to top military officers, and see how they felt it performed in the field.

For his contributions, Belton felt that he was entitled to £1,000 for every 100 rifles he made available to the Continental Army.

Belton justified his price by claiming that a state could not raise, equip, and clothe 100 soldiers for £1,000. For reference, £1,000 in 1777 is the equivalent of £165,000 in 2021. If all 13 states outfitted 100 men, Belton would receive £13,000 – or a cool £2.1 million today. Converted to U.S. dollars, that’s $2.8 million in 2021.

The Continental Congress was short on cash and was hesitant to lay out such significant funds on this new type of firearm. Belton argued that his compensation terms were “vastly reasonable” and that if Congress refused his terms, he wouldn’t do it.

Belton must have realized immediately that his demands were more than outlandish because the next day, on May 8, he wrote a letter to John Hancock lowering his fee to £500 per 100 rifles.

On May 15, Congress quickly dismissed Belton’s new offer. Despite him cutting his price by 50 percent, they still viewed it to be an “extraordinary allowance.” (No one saw that coming, right?) Congress considered the matter dropped and didn’t reply to Belton, likely assuming he would take their lack of reply as a refusal.

They were wrong.

Is Persistence Key?

Having heard nothing from Congress, Belton wrote them again on June 14. This time, he claimed that his rifle could hit targets accurately out to 200 yards. In an era of smoothbore muskets, that was an exceptional claim. Whether or not he could actually back it up was another story. Still, Belton said he would be available to demonstrate this to the Congress on the State House Yard, which is today the grassy field in front of Independence Hall.

Again, he heard nothing for almost a month.

Still undeterred, Belton wrote Congress again on July 10. This time, he started slinging mud. He tried to rile members of the body by claiming that Great Britain regularly pays £500 for such services. Understandably, the founders didn’t take kindly to this comparison.

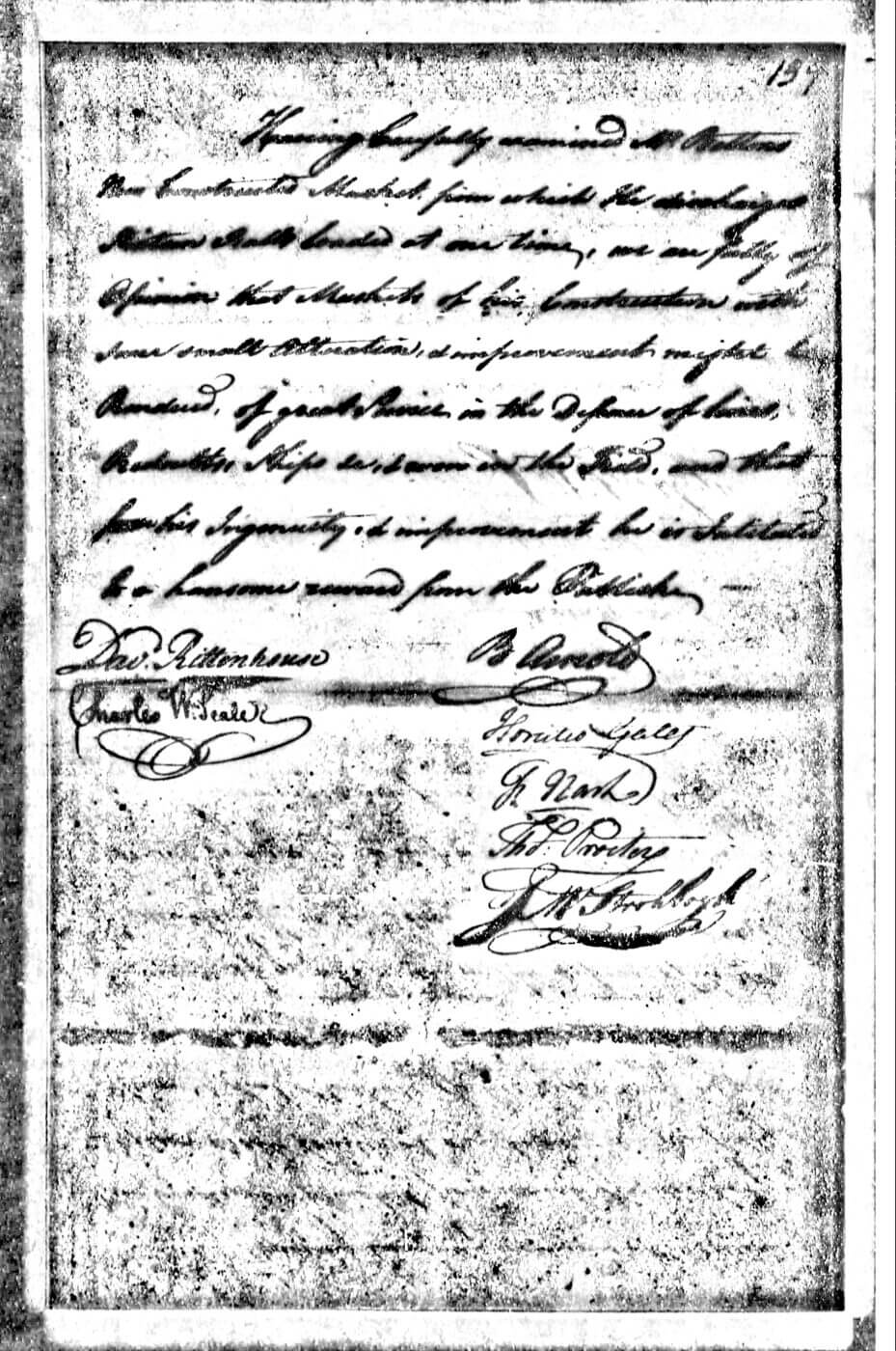

In the same package as this, Belton also enclosed a letter signed by General Horatio Gates, Major General Benedict Arnold (before he became a turncoat), well-known scientist David Rittenhouse, and others, all claiming that his invention would be of “great Service [sic]” and that Belton is entitled to “a hansome [sic] reward from the Publick [sic].”

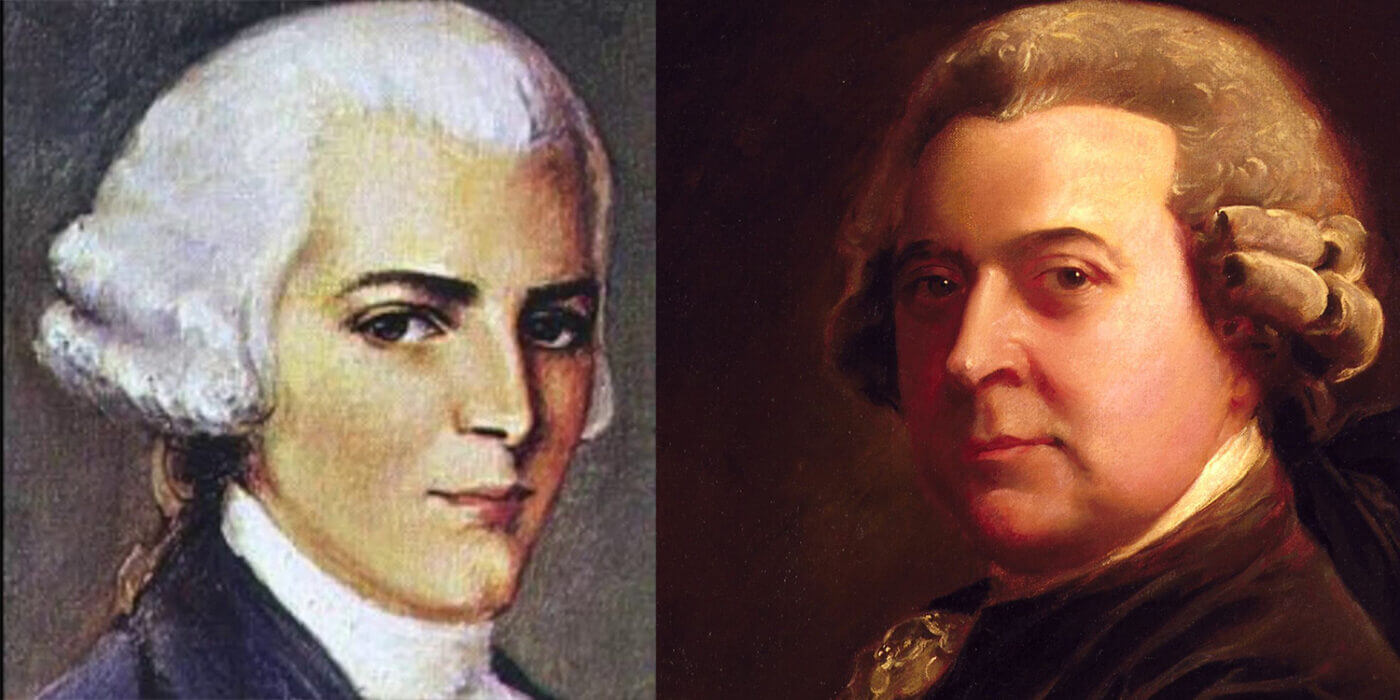

Congress referred Belton’s petition to the Board of War, made up of five delegates. Among these five delegates were the future second President of the United States and the father of the sixth President of the United States, John Adams; and Benjamin Harrison V, father and great-grandfather of the ninth and 23rd Presidents of the United States, respectively.

Nine days later on July 19, Congress got word from the Board of War. They dismissed Belton’s petition altogether. At this point, he must have finally gotten the hint that Congress wasn’t going to authorize such exorbitant payment for his services because the historic record turns up no more correspondence between the two parties. It was also clear that while they were intrigued by the design, it would seem a repeating rifle was not revolutionary enough to warrant purchasing it for use by the armed forces.

The Key Factor

Despite the fact that Joseph Belton failed to convince the Continental Congress to outfit Continental Army soldiers with his repeating rifle, it’s still a very important story because of the timing. Belton invented his gun in 1777 (unfortunately, no known examples exist today), and yet the Bill of Rights — of which the Second Amendment was a part — wasn’t ratified until 1791.

I’m no math whiz, but even I know that means our Founding Fathers knew about repeating rifles several years before the creation of the Second Amendment.

So, the next time someone tells you the Second Amendment was never designed to protect the right to own a repeating rifle, or that it was only meant to apply to flintlock muskets, sit them down and tell them the story of Joseph Belton and his repeating flintlock musket.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

309

309