WWI Body Armor: Plate Mail in the Trenches

November 29th, 2022

9 minute read

At the outset of the Great War, old-world planning ran head-on into the realities of modern technology. Vast numbers of men were thrown into the grinder, and the losses were staggering. Scrambling for solutions, military planners looked backward for one possible answer: armor. With WWI body armor, military leaders looked for a tactical advantage while the men in the trenches looked for any edge to stay alive. In today’s article, Tom Laemlein looks at the trench armor developed during this time and judges its effectiveness. — Editor

Outback Origins of WWI Plate Armor

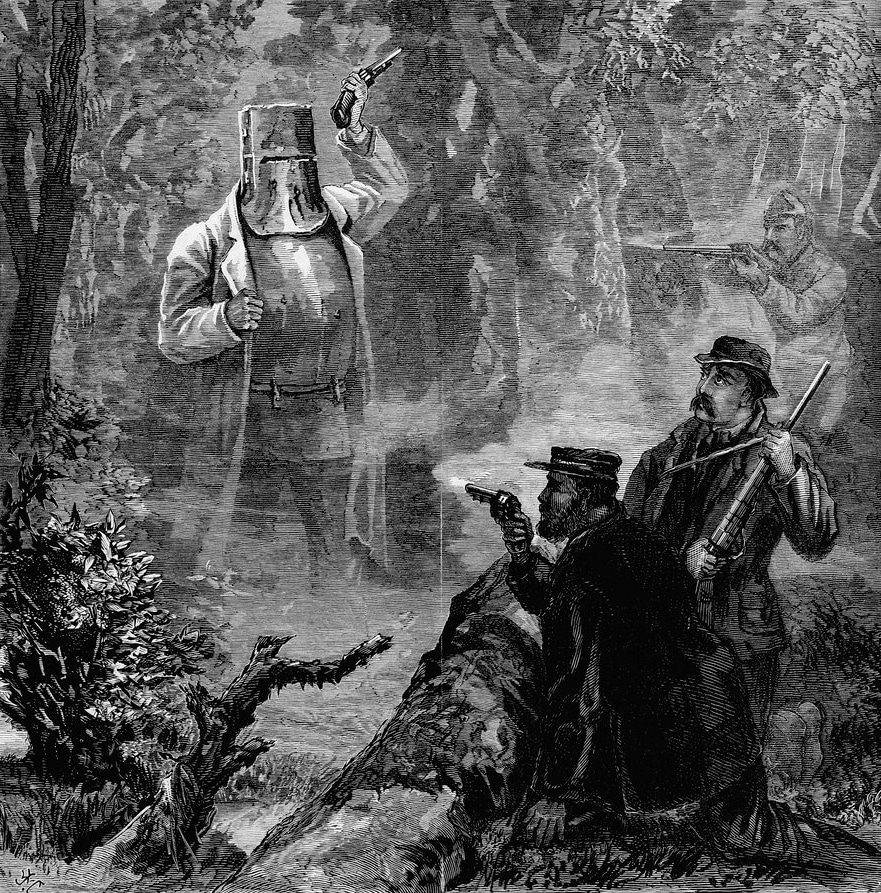

In June of 1880, in the outback of Victoria, Australia, infamous bushranger Ned Kelly brought the idea of body armor back into the mindset of modern military planners. During a 15-minute shootout with police, Kelly wore a bush-forged and crafted suit of armor (weighing almost 100 pounds) and exchanged fire at close range with multiple officers.

Kelly’s armor effectively protected his head and upper body, but his arms and legs were exposed, and eventually he was knocked down by a pair of shotgun blasts that struck his legs. Kelly’s opponents were bewildered and frustrated by the ineffectiveness of their firearms, while the outlaw appeared in the morning mist almost as an apparition, strangely impervious to bullets.

As the bullets found the uncovered areas of his body, Kelly lost a considerable amount of blood, and the weight of his armor became difficult to manage. Each round that struck the improvised armor plate delivered a massive punch to Ned’s head or torso. When he was finally subdued it was found that Kelly had suffered more than 20 wounds. Even so, he survived to be tried and then hanged for his crimes. His body armor became an instant legend and was the subject of much discussion in international military circles. The medieval concept of body armor had been reborn in the modern world.

Kelly’s body armor was crude, but nonetheless ingenious. The forged iron plates were said to be 6mm thick, capable of turning away the commonplace rounds of the time. The hits to the armor caused significant bruising and lacerations, as well as concussive effects. Despite this, Kelly was able to stay in the close-range fight for a surprising length of time.

Did WWI Soldiers Wear Body Armor?

Yes. A variety of plate and other armors were used in World War I.

The rapid advances of military science in the late 19th century included a new look at body armor. The idea of making a foot soldier impervious to enemy fire has always been a goal, and the consequent impact on the morale of the assault troops is an obvious by-product.

But there is always a cost, and with body armor it is measured in pounds. It is a frustrating equation: the greater the protection, the greater the weight. Too much weight and the infantryman turns into more of a statue than a soldier. Not enough protection and the body armor idea becomes a pointless exercise.

As the great powers approached an impending conflict in the early part of the 20th century, there were multiple new threats to the infantryman: high-powered rifles and machine guns, and modern explosive artillery ammunition that continued to grow in caliber and shrapnel effect. When World War I raged, artillery and machine guns would do the overwhelming amount of the killing. Some saw body armor as a smart way to minimize casualties.

Choosing Risk?

In “Helmets and Body Armor in Modern Warfare” by Bashford Dean (Yale University Press 1920), the author and his team went to great lengths to study and measure the effectiveness of body armor (including helmets):

The results of our inquiry will show: (1) That the helmet has been adopted as part of the regular military equipment of many nations. (2) That helmets and body armor have been found, in broad averages, of distinct advantage to the wearers. (3) That body armor, in spite of the protection which it affords, finds little favor with the soldier. For numerous reasons, he would rather take his chances of injury. (4) That effort should be made, none the less, to demonstrate more clearly the protective value of body armor, to improve its material and design, and to reduce to a minimum the discomfort which will always be experienced by its wearer, in a word, to meet the objections to the use of armor which have been brought up on the sides both of theory and of practice.

In a report from Colonel Walter D. McCaw, who has reviewed (June 30, 1918) the latest data at the Service de Sante, the following percentages are given:

“Helmets and Body Armor in Modern Warfare” by Bashford Dean

- Shrapnel or shell fragments: 50.66%

- Grenades: 1.02%

- Rifle or machine gun bullets: 34.05%

- Bombs from aeroplanes: .10%

- Mine explosions: .15%

- Accidental missiles, undetermined: .14.00%

The American Way

“Effort should be continued towards the development of a satisfactory form of personal body armor.” — General Pershing, 1917.

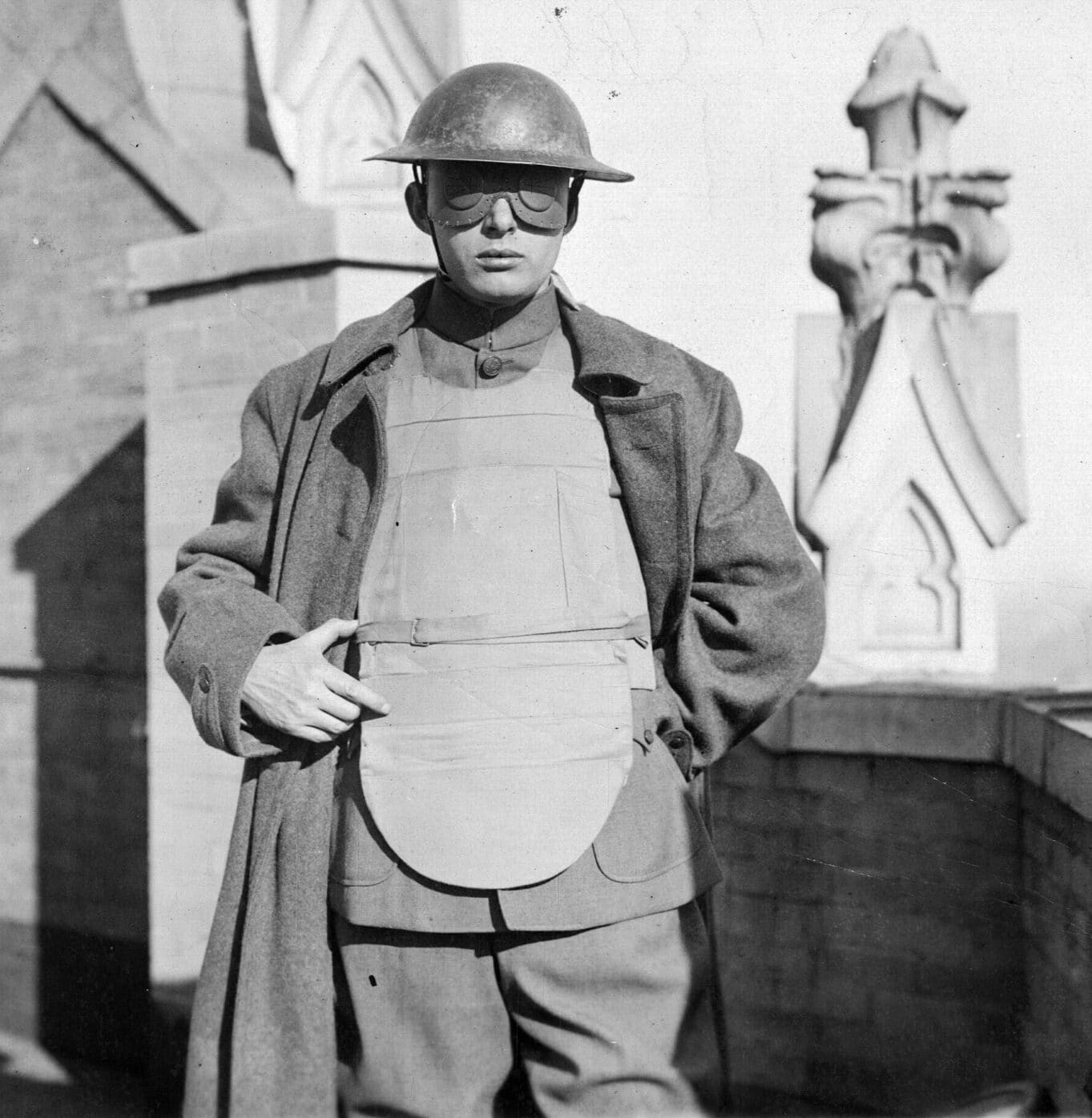

In the United States, there was considerable interest in and development of body armor, particularly after America joined the fight in April 1917. Dr. Guy Otis Brewster developed his cumbersome Brewster Body Shield during 1917. The Brewster armor gave the appearance of a Steampunk stormtrooper or an early concept of a spaceman. However, it’s chrome and nickel steel plate could stop a British .303 bullet at relatively close range.

Dr. Brewster was so confident in his armor that he personally wore it while being filmed as he was shot with an SMLE rifle! Regardless, the massive helmet and breastplate (weighing more than 40 pounds) were never adopted.

Several examples of “light armor” were produced in the United States, particularly from the summer of 1918 onward. Photographs of the Hale & Kilburn manufacturing facility in Philadelphia show a considerable amount of body armor in production in later 1918.

This armor did not reach U.S. troops before the Armistice in November, and it seems unlikely that it was ever shipped to France. Few examples still exist, and it is a bit of a mystery about whatever happened to all that body armor.

American experiments with “ballistic” shaped helmets, along with flexible protection for soldiers’ shoulders, arms, and hands all showed promise, but ultimately the forward-thinking designs did not see combat in 1918.

Like the Allied “Grand Offensive” of 1919, the body armor wasn’t needed. Within a year or so after World War I, the concept was abandoned — at least until World War II came along.

German Trench Armor: Sappenpanzer

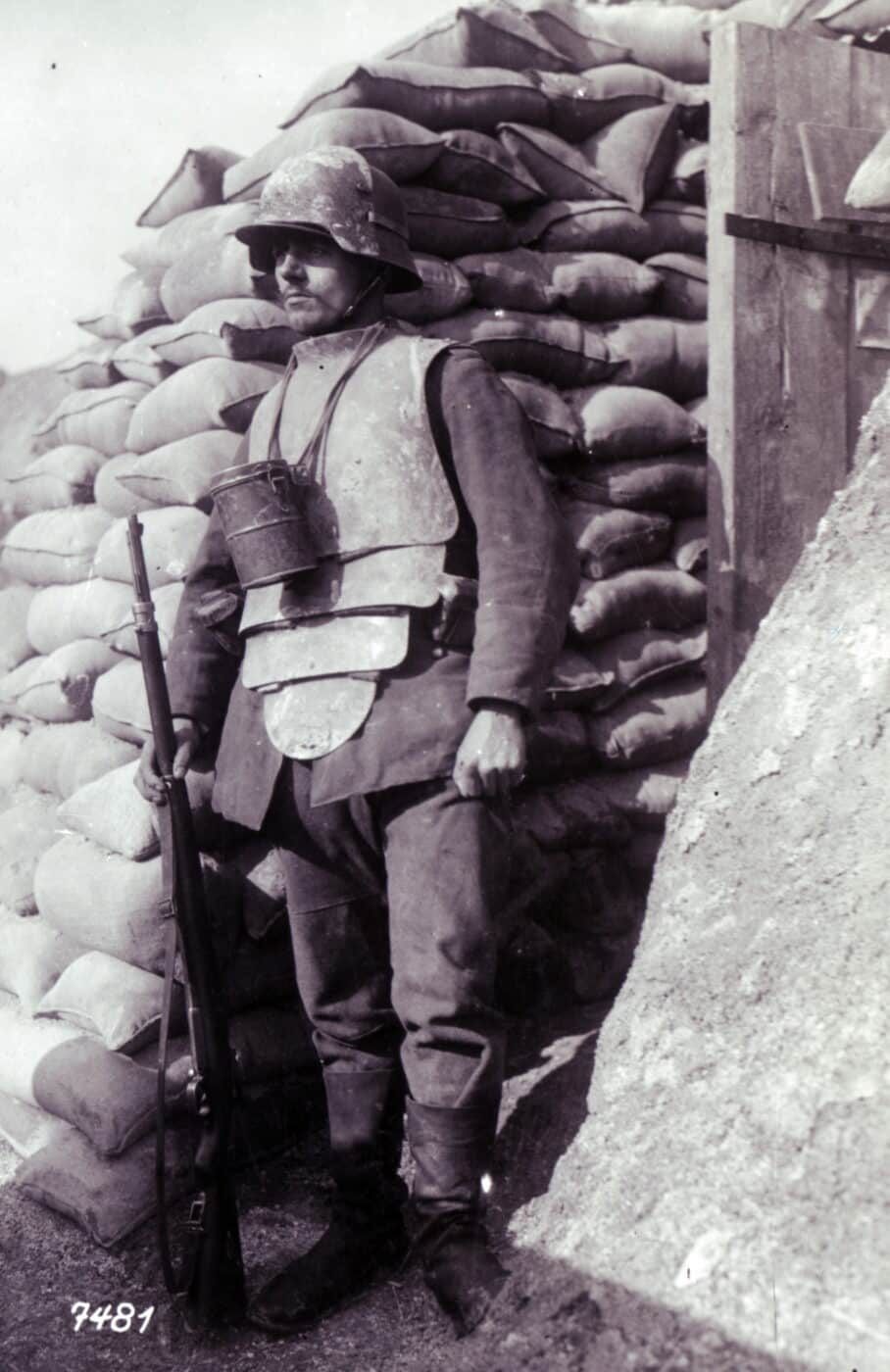

The German Army first issued its body armor in 1916 — the Germans called it “Sappenpanzer”, or trench armor. The armor plate weighed 24 pounds and included an armored brow plate that connected to the German trench helmet.

Normally, the Germans issued body armor to sentries, machine gunners, and occasionally snipers operating from prepared positions in the trenches. German armor offered sure protection against shrapnel and uncertain defense against rifle and machine gun fire.

U.S. ballistic tests with German body armor showed the following:

American rifle ammunition at 2,140 foot seconds pierces at 30 yards but is resisted at 60 yards. Service ammunition of full velocity (2,780 foot seconds) shatters at 60 yards, is resisted at 300 yards.

The Germans saw possibilities with their body armor but were not overly enthusiastic. An officer’s comments outline their attitude in this translated report:

The armour is not generally intended for operations, but it will prove valuable for sentries, listening posts, garrisons of shell holes, gun teams of machine guns scattered over the ground, etc., especially as a protection for the back.

Another report outlines the difficulties brought on by the armor’s weight:

Infantry armour has, on the whole, proved serviceable for sentries in position warfare. Universal complaints have been received that the armour makes it difficult to handle the rifle and is a considerable handicap to bombers. “On the other hand, it is admitted that the armour is very useful, especially as a protection to the back, for individuals (listening posts, advanced posts during a heavy bombardment) and has prevented casualties. “It should not be used for operations which entail crossing obstacles by climbing, jumping, or crawling, especially as it makes it difficult to carry ammunition. When the enemy attacks, the armour has to be taken off, as it decreases the mobility of the soldier on account of its weight and stiffness.

Photos show that in the spring offensive of 1918, some German assault units wore body armor in the attack, but all evidence points to the fact that the weighty plates limited the Stosstruppen’s mobility, undoing any protection the armor offered. Allied troops treated the German armor as a curiosity, and multiple photos show that they treated it as a prize souvenir with some utility.

Conclusion

While body armor might be extremely common today, the foundations for today’s innovations were being laid in the trenches of World War I. Necessity truly may be the mother of invention.

Editor’s Note: Please be sure to check out The Armory Life Forum, where you can comment about our daily articles, as well as just talk guns and gear. Click the “Go To Forum Thread” link below to jump in and discuss this article and much more!

Join the Discussion

Continue Reading

Did you enjoy this article?

245

245